ABSTRACT

With digitalisation, the male-dominated bioeconomy sector becomes intertwined with the male-dominated tech sector. We focus on the effects on gender equality within the bioeconomy sector when these two gender unequal sectors are merged. We review the existing literature by studying three concepts – bioeconomy, digitalisation and gender – as a way to highlight the current state of knowledge on gender in the Nordic digitalised bioeconomy. Through this investigation we provide directions for future research and suggest actions to be taken. The contemporary literature discusses two major areas of focus: the impact of history on today’s situation and gender inequality as a women’s issue. We propose four areas of future research focus: moving beyond a historical perspective, understanding the effectiveness of women-only activities, focusing on men’s role in gender equality work, and developing sustainability. We identify four points of action for practitioners in the literature: female role models, mentorship programmes, networks for young professionals and students and incorporating gender into bioeconomy-related education. However, together with the proposed future research, we suggest two considerations when practitioners in the Nordic digitalised bioeconomy take action: being mindful of the purpose and structure of women-only activities and including men when working with gender issues.

Introduction – investigating the current state of knowledge on gender in the digitalised bioeconomy

The bioeconomy is a sector of growing importance for the Nordic economies (Nordic Council of Ministers Citation2018). It is also a male-dominated sector. Women’s participation is increasing, but the slow growth rate and low starting point imply that the gender imbalance persists. History shows that the more mechanised the sector, the more it becomes associated with masculinity (Heggem Citation2014). This exemplifies one of the challenges which needs to be acknowledged and addressed to ensure an inclusive development of the Nordic bioeconomy. An inclusive and gender-balanced bioeconomy is important for several reasons, not the least of which is the important of internal diversity for achieving innovation and sustainability within the sector.

The digital transformation and automation of physical jobs could, in theory, reduce gender bias; however, the reverse appears to be true (Larasatie et al. Citation2020). While digitalisation removes the physical dimension, it requires other non-physical skills and attributes which are also male dominated, such as university degrees in digital technology. Hence, the digital transformation may further entrench the current power structure. As digitalisation is already happening in the bioeconomy (Ingram and Maye Citation2020) and is an inevitable change also in the rest of society (Sorama Citation2018), the implications on gender issues from digitalisation is thus an important aspect for the future of the bioeconomy, if we aim for the sector to be more gender balanced. Hence, a situation that calls for action.

With these concerns in mind, in this review we set out to investigate the current state of knowledge on gender in the digitalised bioeconomy, to provide directions for future research and suggest actions to be taken. The research question that follows from this aim is: what do we know about how the digital transformation affects gender inequalities in the Nordic bioeconomy? While there some recent publications have studied the issue of gender in relation to the digitalised bioeconomy (e.g. Korsvik et al. Citation2020), the literature is still sparse. By instead studying the three concepts in dyads (gender in the bioeconomy, digitalisation of the bioeconomy and gender in digitalisation), this review identifies the most frequently studied narratives in the literature. The results of this review provide direction for future research on gender in the digitalised bioeconomy.

In the next chapter, we lay out how we collected and analysed the literature. After that we lay out the results of our analysis, presenting the topics in the literature by dyads (gender and bioeconomy, digitalisation and bioeconomy, gender and digitalisation). We then discuss the current state of knowledge within research on gender in the digitalised bioeconomy. We conclude the review by proposing four directions for future research and two considerations for actions.

Defining the concepts

The concepts that this review focuses on – gender, bioeconomy and digitalisation – are complex in themselves. We use these concepts to understand the current state of knowledge within research on gender in the digitalised bio economy. In this research, gender is understood as a social construct constantly produced by people in their use of symbols, language and actions (West and Zimmerman Citation1987). Beyond biological determinants, notions of gender shape and are shaped by roles, social relations, societal structures, household patterns and communities (Lorber Citation1994). This reproduction can be done with intent and direction, or unintentional and in the moment (West and Zimmerman Citation1987). First, gender restrict what is possible for women and men to do, such as taking part in different societal processes (Acker Citation1990). Second, gender might be purposefully used to achieve certain goals. We can see how people use the practices that gender make available to enhance their status (Martin Citation2006). People work within the norm and conform to gender constructs. Finally, people can also provoke and challenge gender constructs through questioning and reinterpreting norms (Brandth and Haugen Citation2010).

In this paper, bioeconomy is defined as “an economy where the basic building blocks for materials, chemicals and energy are derived from renewable biological resources” (McCormick and Kautto Citation2013, p. 2589). We can contrast the bioeconomy with the fossil economy, where the building blocks come from non-renewable resources (Refsgaard et al. Citation2021). As such, the focus is on water and land use in bioeconomy. In this review, we have the resource in focus as the Nordic countries have a surplus of these resources in relation to the basic human needs in the region (Refsgaard et al. Citation2021). However, through our literature review, it becomes clear that within research, bioeconomy in the Nordic countries primarily refers to agriculture and forestry.

Finally, we consider digitalisation as a process of comprehensive technical changes but also social and organisational changes (Rolandsson et al. Citation2020). This includes the conversion of information from analogue to digital format. Digitalisation is one of the “megatrends” shaping our society (Sorama Citation2018) where it has been described as revolutionising work life and is being presented as “Industry 4.0”. This entry of “cyber-physical systems” has resulted in the automation of certain jobs using decentralised decisions and communication through an internet of data and services (Krzywdzinski et al. Citation2016).

Together these three concepts form the basis for our review.

Method – A review on the literature on gender, bioeconomy and digitalisation

This review aims to further investigate the current state of knowledge on gender in the digitalised bioeconomy and provide directions for future research and suggest considerations when developing actions. Our main interest in doing so is to identify how researchers understand the intersection between gender, digitalisation and the bioeconomy in both conceptual and empirical papers. We looked for how researchers use these concepts in dyads (gender in the bioeconomy, digitalisation of the bioeconomy and gender in digitalisation). We reviewed each of the three dyads using the same approach and analysis.

Approach

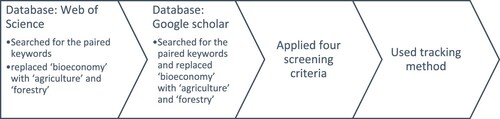

We selected Web of Science and Google Scholar as our search engines due to their wide coverage of the literature and quality assurance (Appelstrand and Lidestav Citation2015; Filyushkina et al. Citation2016; Roos and Gaddefors Citation2017). We went with Web of Science instead of Scopus to avoid the probable publisher bias from Elsevier. Additionally, we also complemented our curated data base with Google Scholar since Google Scholar also cover other types of scholarly communication beyond published journal articles.Footnote1 In we present our research flow scheme.

We conducted the searches in October and November 2020. We chose the paired keywords “gender/bioeconomy”, “digitalisation/bioeconomy”, and “gender/digitalisation” to build the searches. We used these rather broad keywords to try and capture the context of our focus. The Boolean search AND was not used since we only use two keywords at a time, and the Boolean search “” was not used since we were not only interested in documents that had the keywords as an exact phrase. For the two dyads concerning bioeconomy, our initial overview found that the concept did not capture the content to the extent we wanted. Hence, we followed Frank and Hatak (Citation2014) and replaced “bioeconomy” with searches for “agriculture” or “forestry”. As seen in the search terms rendered on one occasion over 2 million hits and many times more than a thousand hits. To be able to sift through the material we decided to look at the first 150 hits based on relevance in both our databases.

Table 1. A summary of the literature search.

We used four screening criteria to include and exclude documents relevant to our review: language, year, geographical area, and type of document (Frank and Hatak Citation2014). 1) We selected English as the search language and used it as a selection criterion. While this excludes potentially interesting literature in the other languages (especially the Nordic languages), it ensured a stringent approach that eliminated any challenges caused by translation. 2) Since the digitalised bioeconomy is developing at a fast pace (Watanabe et al. Citation2019), we felt that only recent documents were relevant and therefor limited our searches to literature published between 2015 and 2020. 3) Because our study was interested with issues in the Nordic countries, we excluded documents focusing on areas outside of the Nordic countries or North America. North America was included based on its greater similarities to the Nordic countries when it comes to environmental- and organisational structures within forestry and agriculture, as well as their concerns and questions with gender equality. 4) We included peer-reviewed, academic literature such as conference proceedings and journal documents, and “grey” literature such as policy and industry reports. We included this range of literature because we wanted to capture the current state of knowledge and thinking in the field as reflected in concepts and papers not yet published in peer-reviewed journals (Frank and Hatak Citation2014). This process yielded some 50 documents per dyad.

presents a compilation of the literature fulfilling these criteria. Removing duplicates left 149 items for analysis. These 149 documents are listed in Appendix 1 as no 1-149. We used a tracking method to identify additional relevant documents in the reference sections of the first 149 items gathered through the search. This method yielded twelve additional documents for the analysis. These twelve documents are listed in Appendix 1 as no 150-161.

Analysis

Our sampled items are heterogeneous when it comes to methods, theory and their sample. Because of this we decided to use narrative analysis (Frank and Hatak Citation2014). Our analysis of the literature consisted of two steps. First, each literature item was subsequently reviewed and ranked from one to three on relevance to the topic studied (one being the most relevant). The ranking can be seen in Appendix 1. During the ranking process we also revisited the four screening criteria and gave any document that did not match a rank 3. This was to double check our first screening with our smaller sample. Second, from the ranking, we constructed narratives (Czarniawska Citation1998) using the most pertinent literature within each dyad. This allowed us to tease apart the contemporary narratives within our topics. Even though the documents varied in time and place, they were connected through narratives in the research process (Boje Citation2001). We identified the three most often-addressed narratives within each dyad to identify the challenges, solutions and perspectives in play for the dyad in question.

However, looking at the sample, most studies on bioeconomy concerned forestry, very few focused on agriculture, and almost none on other areas of the bioeconomy. This is reflected in our results, where bioeconomy primarily refers to forestry and secondly to agriculture.

Results – the most frequent narratives within research on gender, bioeconomy and digitalisation

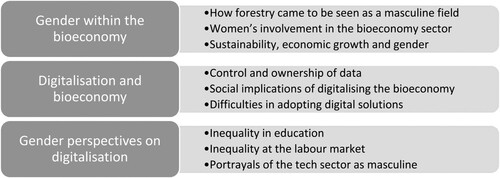

presents the main narratives in the studied dyads (gender and bioeconomy, digitalisation and bioeconomy, gender and digitalisation). The gender and bioeconomy literature focuses on understanding how the bioeconomy (especially forestry) became male-dominated, symbolically as well as in practice. The identified studies also investigated how symbolic masculinity materialises in everyday practices that shape the gender imbalance within the sector.

Figure 2. The main narratives in gender and bioeconomy, digitalisation and bioeconomy, and gender and digitalisation.

Within the literature on digitalisation and bioeconomy, the most prominent discussions concern the use of data. Researchers also raise questions about shifting preconditions for the bioeconomy workforce, changing business models and the value of forms of knowledge other than those of traditional farming and forestry.

The literature that offers a gendered perspective on digitalisation focuses on how masculine and feminine stereotypes and the masculine construction of technology is clearly present both in education and in the labour market today. This discourages women from entering the tech and digital industries and higher education. We will now turn to these main narratives within our studied dyads and elaborate on their content.

Gender within the bioeconomy

The first narrative in this dyad focuses on how gender issues in the bioeconomy shape everyday work practices. The second narrative focuses on why gender imbalances prevail in the bioeconomy and how current structures affect gender inequalities. The third and final narrative focuses on using the lenses of economic opportunity and social justice to analyse the relationship between sustainability, economic growth and gender.

How forestry came to be seen as a masculine field

Forestry has traditionally been seen as a masculine sector (Johansson and Ringblom Citation2017; Östlund et al. Citation2020). During the preindustrial era, women and men commonly shared agriculture and forestry duties, but with increasing mechanisation of these tasks, traditionally feminine duties were recoded as masculine. Working with machines and technology made led to certain tasks being considered more suitable for men.

However, recent historical studies have aimed to understand women’s early contributions in forestry, diversifying the historical notion of forestry as a masculine field. These studies suggest that women have been an important part of different types of forestry labour in history (Östlund et al. Citation2020).

While the masculine narrative still largely prevails in practical labour, women’s role in forestry is growing, both as forest owners and as students in the field (SNS Citation2020). Nonetheless, differences in ownership, management and operation between women and men are evident (Follo et al. Citation2017). While many forest owners do not notice that there are gendered differences impacting ownership, the work conducted is still largely divided along gender lines (Bergstén et al. Citation2020). This means that women have more constrained access to opportunities to acquire the skills and knowledge needed in forestry, since men mostly carry out the actual work in the forests.

Women’s involvement in the bioeconomy sector

The proportion of women studying forestry at the university level has increased. Yet, this increase has not been reflected in workplaces (Larasatie et al. Citation2020). Up to 84% of women engaged in the field have experienced barriers at their workplaces due to their gender (Bardekjian et al. Citation2019). This is partly due to perceptions and representations but also due to discursive resistance towards gender equality programmes (Johansson K. et al. Citation2020). Gender equality programmes have thus sometimes led to further reinforcement of the association between competence and masculinity and the naturalisation of gender inequality (Johansson K. et al. Citation2020).

Women face barriers in their access to networks of knowledge, which halts their career development and upholds persistent stereotypes that frame women as less capable of duties related to forestry (Andersson and Lidestav Citation2016). The literature also points to sexual harassment and sexist behaviour as major barriers for entering and staying in the field (Grubbström and Powell Citation2020; Johansson et al. Citation2018; Larasatie et al. Citation2020). Such treatment is also seen to reinforce the gendered stereotype of women as less competent in forestry professions (Johansson et al. Citation2018).

Several studies have debated the best strategy to increase women’s involvement in the forestry sector, including sponsorship and mentoring, confidence-building, inclusive communication strategies, enhancing work-life balance, career planning and combating sexism and harassment. These strategies aim to make the workplace culture more inclusive and to create support mechanisms for women in a male-dominated field, as well as to tackle practical challenges that female workers often face within the sector (Bardekjian et al. Citation2019; Johansson et al. Citation2018).

Another much-debated strategy is diversification of leadership positions. Some argue that having more women in leadership positions benefits companies not only in terms of turnover and competitiveness but also the level of inclusiveness in the company’s organisational culture (Baublyte et al. Citation2019; Johansson and Ringblom Citation2017). However, some studies have shown that having women in leadership positions does not translate into more inclusivity. Some studies suggest that women leaders do not see themselves through a gendered lens, meaning that they may indeed have moulded themselves to the masculine norm in order to thrive in the field (Baublyte et al. Citation2019). Indeed, stakeholder respondents indicate that even though women are being recruited for top leadership positions, the sector as a whole has not necessarily become more inclusive because organisational cultures still adhere strongly to masculine norms (Larasatie et al. Citation2019). This is evident in company management cultures that revolve around sauna culture or hunting, for example.

Sustainability, economic growth and gender

With increasing demand for sustainability, the Nordic bioeconomy represents a forward-looking alternative to societies built on fossil fuels (Bracco et al. Citation2018). With the growing importance of the bioeconomy, gender inequality has important and far-reaching implications in relation to sustainability, social justice and business opportunities (Lidestav et al. Citation2019; Linser and Lier Citation2020; Mattila et al. Citation2018). We identified two major streams of thought in the literature on gender, bioeconomy and economic growth.

First, as the bioeconomy becomes more important, it will generate an increasing need for workers and innovation (Hansen et al. Citation2016; Holmgren and Arora-Jonsson Citation2015). Some authors emphasise the need to diversify the sector in order meet the need to increase the size of the workforce and to enhance innovation in the sector (Holmgren and Arora-Jonsson Citation2015). This reasoning is strongly linked to the “industrial needs” argument, which sees gender equality in a rather depoliticised way and treats it as a subject of managerial practice (Holmgren and Arora-Jonsson Citation2015; Johansson and Ringblom Citation2017).

Second, some scholars analyse the underlying inequalities in the sector through the lens of social sustainability and justice. Gender inequality hinders growth and exacerbates the division between “winners and losers”. As a male-dominated sector, the increasing importance of the bioeconomy will thus benefit men disproportionally compared to women (Hasenheit et al. Citation2016). The arguments that follow this line of though call for greater inclusion as a way to create and secure the socially sustainable development of bioeconomy.

Digitalisation and bioeconomy

The first narrative we found in literature focuses on how the presence and usage of data in the bioeconomy drives questions of data ownership and governance. The second narrative focuses on social sustainability in light of the digitalised bioeconomy and how farmers are positioned compared to large corporate actors. The third narrative focuses on the challenges of technology adoption within digitalisation.

Control and ownership of data

As the bioeconomy becomes increasingly digitalised, vast amounts of collected data need to be managed and analysed in order to bring value (Ingram and Maye Citation2020; Shepherd et al. Citation2020; Wolfert et al. Citation2017). Hence, having the ability and capacity to conduct these analyses is key. This new demand has resulted in the development of new business models, ventures and collaborations.

Looking at this rich data from the perspective of the farmer raises questions about data ownership, control and reliability (Regan Citation2019; Rotz et al. Citation2019a; Wolfert et al. Citation2017). To use the hardware and software offered by the agricultural machinery sector, farmers must agree to certain terms and conditions. However, in doing so they often surrender their rights as to who controls their data (Rotz et al. Citation2019a). Wolfert et al. (Citation2017) further highlight how farmers are concerned not only about who benefits from the data but also about who has access to it. This further highlights the concern that control of the data often remains with technology providers rather than the farmers themselves. This raises questions about data governance, and Regan (Citation2019) points to the importance of including farmers in the process of developing technologies and governance models so that the benefits they seek from digitalisation are taking into consideration.

Rotz et al. (Citation2019a) emphasise the inclusion of farmers in the development phase and as part of discussions of open-source models to ensure that the technology and data is owned directly by the farmers, granting them more financial power. One of the main challenges in digitalising the bioeconomy is need for a more open and collaborative data culture between farmers, businesses, researchers and governmental bodies (Klitkou et al. Citation2017). Aspects concerning control and ownership of data therefore need to be focused on and resolved.

Social implications of digitalising the bioeconomy

The digitalisation of the bioeconomy entails significant social implications, both positive and negative. The literature suggests that digitalising the bioeconomy – as with digital transformations in many other sectors – benefits some groups more than others (Rotz et al. Citation2019b). The technical solutions being developed seem to favour large corporate actors at the expense of independent farmers and other smaller actors (Finger et al. Citation2019; Rotz et al. Citation2019a), in particular due to the cost of the technology for smaller farmers. Technologies and business models need to focus on aspects other than lowering the cost of inputs if they are to be relevant for small-scale operations and lower-value crops (Finger et al. Citation2019).

The literature also raises concern about the effects of digitalisation and surveillance on the workforce. Traditional labour hierarchies are increasingly supplanted by technological tools, and the relentless drive for efficiency will subject workers in the field to increased surveillance and spiralling expectations of productivity. At the same time, a small number of highly skilled workers will know how to use digital technologies to increase productivity (Rotz et al. Citation2019b). On the same note, Rose et al. (Citation2021) highlight the potential for increased use of technology to marginalise practical knowledge and ultimately lead to a disconnect between workers and the landscape. However, Rotz et al. (Citation2019b) argue that increased digitalisation could benefit these marginalised groups by increasing transparency within the sector, with favourable effects in terms of labour conditions and fairness.

Rose et al. (Citation2021) underline the importance of incorporating social sustainability into technological trajectories using methods such as outlining a framework that favours multiple actors and encourages co- innovation, in order to ensure that socio-technical transitions are sensible. Furthermore, Rotz et al. (Citation2019b) argue that we need to consider society’s role in improving the lives of the most vulnerable workers and their future livelihoods. If the benefits are not equally shared, Rose et al. (Citation2021) suggest that the potential productivity and environmental benefits of the digital transformation will not achieve their full potential.

Difficulties in adopting digital solutions

Knierim et al. (Citation2019) raise questions about usefulness of technologies in terms of their compatibility with existing farming technologies and routines. While farmers are interested in the value that digital technology brings to their farming, they are not directly interested in the technology itself, which means they have few incentives to improve their digital competence.

This is a critical problem for Swedish forestry that is present throughout the value chain: a lack of necessary digital competence creates a dependence on outside expertise (Holmström Citation2020). Research also shows that many farmers think it is difficult to identify when and where to invest resources in new digital solutions (Holmström Citation2020). This may in part be due to farmers considering a wide range of technological possibilities when investing (Holmström Citation2020; Knierim et al. Citation2019), which takes time and slows down the process of digitalising the bioeconomy.

Gender perspectives on digitalisation

The three narratives emerge at the intersection of gender perspectives and digitalisation: inequality in terms of education, inequalities in the labour market and the ways different gender constructs and stereotypes are portrayed as masculine within the tech sector.

Inequality in education

One way to promote greater gender balance in the digitalisation process is through education, especially higher education. Women represent only 25% of students in the IT sector (Mozelius Citation2018). One study examining ICT education found that more than 75% of supervisors were men, and the most common type of discrimination in ICT education is gender-based (Koskivaara and Somerkoski Citation2020).

If we do not succeed in correcting the imbalance in educational opportunities for women in tech, we inevitably reproduce existing inequalities in the workplaces (Piasna and Drahokoupil Citation2017; Warmuth and GlockentGlockentöger Citation2018). Most female students in ICT fields aspired to a successful career in the IT sector, but existing gender stereotypes mean they believe it is unlikely that they will achieve their career goals (Pechtelidis et al. Citation2015).

Women’s participation in ICT high education has been strongly encouraged and has been boosted by activities such as computing camps for girls (Lee et al. Citation2015). Participants have highlighted the positive effects of creating safe spaces and opportunities to experiment and play with technology (Lee et al. Citation2015), as well as increasing interest in the area in non-traditional ways. Larsson and Viitaoja (Citation2019) argue that changes in attitudes and behaviours have a greater impact than policies and regulations; therefore, female role models and promotional campaigns are more importance for attracting girls to these areas. However, despite this awareness and active work against imbalances and discrimination in ICT education, the persistent masculine associations of ITC fields have hindered women’s enthusiasm for envisioning a future for themselves in the field (Sorama Citation2018).

Inequality at the labour market

Most of the literature relating to digitalisation and the labour market deals with the opportunities and risks associated with this new world of work. Abrahamsson and Johansson (Citation2020) illustrate this with two possible scenarios: one where digitalisation acts to strengthen existing male domination of industries such as mining, and the other one where it opens the prospect of undoing gender bias in the sector. They emphasise that the later scenario may be too optimistic. Existing inequalities can be exacerbated by digitalisation (Johansson J. et al. Citation2020) while it simultaneously creates new labour opportunities such as enabling women to gain access to labour markets (Beliz et al. Citation2019; Rajahonka and Villman Citation2019).

There is no clarity in the literature as whether female-dominated or male-dominated jobs are more affected by the automation of tasks in the digitalised labour market. Some have argued male-dominated jobs are more likely to be affected than female-dominated jobs. This since more women work in the domestic service and healthcare sectors which are sectors not expected to be affected by digitalisation (Peetz and Murray Citation2019; Sorgner et al. Citation2017). Also, because women are considered to have better social and leadership skills, which are expected to play a crucial role in the age of digitalisation, this may present an increased opportunity for women (Krieger-Boden and Sorgner Citation2018). Others argue that women are more likely than men to work in jobs involving service and sales tasks and are thus affected by automation to a higher degree (Brussevich et al. Citation2018). Since women are underrepresented in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM), women are generally thought to be less likely to be positively affected by increasing digitalisation (Peetz and Murray Citation2019; Piasna and Drahokoupil Citation2017; Sorgner et al. Citation2017).

With this, many documents also propose solutions and identify crucial topics for governments to take into consideration in order to ensure equal employment opportunities and jobs for all. These studies call for incentives and support for women’s access to STEM fields through education rather than putting the burden on women themselves to break the glass ceiling (Brussevich et al. Citation2018; Sorgner et al. Citation2017; Sorgner and Krieger-Boden Citation2017). Creating women-only activities for knowledge sharing and networking is seen as a tool to foster women’s participation in ICT and STEM fields (Pröbster et al. Citation2018).

Portrayals of the tech sector as masculine

Technologies and opportunities in the digital era are generally considered to be fields intended for men. Studies that examined participants’ attitudes towards opportunities revealed that women often saw technology, data, and digitalisation as masculine fields. This notion hinders women’s enthusiasm for entering these fields (De Vuyst Citation2018; Franken et al. Citation2018; Schuster and Martiny Citation2016) and creates a tendency for women to be less vocal about their technology interests and to downplay their competence in the area (De Vuyst and Raeymaeckers Citation2019). The masculine construction of technology and digitalisation is also present in concrete ways with regards to women’s access to knowledge, their ability to perform work-related tasks and in negative stereotyping and harassment (De Vuyst Citation2018; Terrell et al. Citation2017).

Gender stereotypes further enforce segregation and undermine professionalism (Padovani et al. Citation2019). Abrahamsson and Johansson (Citation2020) found that masculinity, in the sense of traditionally masculine forms of work such as mining, is changing as digitalisation is changing the sector. However, it is still believed that men will continue to dominate within these sectors and their workforces, albeit in a different manner, due to the continued generalised association between masculinity and technology (Abrahamsson and Johansson Citation2020; Johansson J. et al. Citation2020).

Discussion – the current state of knowledge

This review attempts to answer the question of how the digital transformation affects gender inequalities in the Nordic bioeconomy. To address this question, we turned to the literature reviewing the current state of knowledge on gender, bioeconomy and digitalisation. We studied the three dyads (gender and bioeconomy, digitalisation and bioeconomy, and gender and digitalisation), with the aim of identifying and presenting the most frequent narratives within these dyads. After analysing the three dyads separately, the narratives in stand out.

However, when we examine the intersection of the concepts of bioeconomy, digitalisation, and gender, it is evident that research on gender in the digitalised bioeconomy is scarce and is an intersection that does not seem to attract researchers’ or research funders’ attention. Nonetheless, the current state of knowledge on how the digital transformation affects the gender balance in the Nordic bioeconomy focuses on two different aspects: how history affects today’s situation and gender inequality as a women’s issue.

The historical view points out that while the bioeconomy workforce is changing (Larasatie et al. Citation2020), historical stereotypes prevail (Andersson and Lidestav Citation2016). In practice, gender roles have been shaped by socio-historical processes, which in the case of the bioeconomy (mainly forestry) led to the sector being seen as masculine (Johansson and Ringblom Citation2017). Today, these socio-historical processes operate through the structures that maintain a high gender imbalance in bioeconomy, especially in leadership positions. Due to this inequality, economic growth potential is limited, and economic and social outcomes and opportunities are not equally distributed. As a result, the bioeconomy is not socially sustainable (Hasenheit et al. Citation2016).

It is no longer only farming and forestry knowledge that is valued but also competence in data management and technology (Holmström Citation2020). There is, furthermore, an increasing workforce demand for data scientists and technology experts throughout the bioeconomy sector (Ingram and Maye Citation2020; Shepherd et al. Citation2020; Wolfert et al. Citation2017). The fact that both the bioeconomy (Johansson and Ringblom Citation2017) and technology (Schuster and Martiny Citation2016) sectors are largely male dominated, along with the need to meet the changing requirements in terms of workforce skills, could further motivate the greater inclusion of women. As has been pointed out, the stereotype is that bioeconomy jobs require heavy labour, and so the momentum from changes in workforce demand could be used to attract more women and reshape stereotypes of bioeconomy workers. Once the new standards are set, however, they tend to be more rigid and difficult to change (Acker Citation1990). Thus, it is critical that we take advantage of this current momentum.

Secondly, the sole focus on women’s role within work for gender equality is evident. This focus is understandable since most workers in technology are men, and there is thus a wish for a shift towards a more gender equal distribution of the workforce (Padovani et al. Citation2019). Literature on both digitalisation (Krieger-Boden and Sorgner Citation2018) and the bioeconomy (Baublyte et al. Citation2019) highlight the need for female leadership, mentorship and networks in order to attract more women to these sectors and to make more women thrive within these sectors. We question whether it is fair to add even more activities to women’s schedules that do not necessarily contribute to their career advancement. A better understanding of these aspects is needed. According to the studies we explored in this review, women’s access to the tech and bioeconomy sectors and other male-associated domains is still hindered by stereotypical images of women and men (Abrahamsson and Johansson Citation2020), sexist behaviour (Grubbström and Powell Citation2020), everyday gendered practices (Bergstén et al. Citation2020) and other issues of access (Andersson and Lidestav Citation2016). Hence, practices that involve both women and men on all levels within the sector. Solely focusing even more on women’s role within these practices will only get us this far as men’s roles are let out of the discussion. To harness its full potential, the Nordic bioeconomy needs to address these gender issues and not only focus on half of the solution, i.e. not only focus on women’s role in gender equality work.

Of course this study is not without its limitations. Foremost, the limitation lies in how we have posed the research question and how we have addressed it. Our criteria is a clear limitation and with no doubt we would have a different result if the criteria was different. With our already set focus on the Nordic countries means that this research is only applicable to the Nordic region. Nonetheless, the criteria serves our research question well. Further, our narrow definition of bioeconomy (as forestry and agriculture) means that the whole scope of the potential in the sector is not in focus. Perhaps fishery and the processing of biological resources would tell us a different story of gender and digitalisation. Here we also want to pay attention to the lack of research on agriculture and gender in the Nordics countries during the last years. As pointed in our paper, the documents in the gender/bioeconomy dyad are almost exclusively about forestry and gender. Hence, as clear research gap emerges in this specific dyad.

Conclusions – directions for future research and suggested considerations for taking action

When reviewing the literature on gender, the bioeconomy and digitalisation, we found that research focuses on how history affects today’s situation and how gender inequality is seen as a women’s issue. The gender and bioeconomy literature focuses on understanding how the bioeconomy became a field with masculine connotations, symbolically as well as in practice. Within the digitalisation and bioeconomy literature, the most prominent discussions include the use of data, social sustainability and challenges in adapting to new technologies. Finally the literature on gender and digitalisation addresses stereotypes and the masculine construction of technology, education and labour market issues and gender equality. Based on this review, we have identified future directions for fellow researchers and offer some practical implications.

Foremost, we argue that we need to pursue further research at the intersection of digitalisation, bioeconomy and gender, as this particular area of focus has received little attention as of today. In order to develop a more sustainable bioeconomy, we need to better understand how the digital transformation affects the gender balance in the bioeconomy. A sustainable digitalisation of the bioeconomy sector is crucial because of the sectors growing importance for the Nordic economies (Bracco et al. Citation2018). From this current state, we propose four avenues for research on gender in the digitalised bioeconomy to that will help achieve a more sustainable sector: moving beyond historical perspectives, understanding the effectiveness of women-only activities, focusing on men’s role in gender equality work, and developing sustainability.

First, we need to move beyond the historical perspective on gender balance within the digitalised bioeconomy. The historical perspective is crucial in understanding why things are the way they are today. But we also need to focus on the future and what can be done to advance gender equality within the digitalised bioeconomy. Here we envision studies that focus on the next generation of workers within the digitalised bioeconomy – today’s students. Drawing on their expectations and knowledge about the sector will help researchers to be more centred in the present. By student we mean both women and men, a position that connects to our third point, which we will come to shortly. Also, we envision studies that look at gender and management within studies of digitalisation. Questions such as who owns the data and who the data is for can offer new perspectives through a gender lens. This is especially relevant for the bioeconomy, since power relations between smaller business owners and larger companies are evident (Finger et al. Citation2019).

Second, we need a better understanding of how women-only activities can advance or hinder gender equality in the digitalised bioeconomy. Much of the reviewed literature advocates for women-specific groups, programmes and other changes, but it is still unclear how effective these activities are. Women-only activities have been critiqued and questioned in other research areas, where they are seen as ineffective (Durbin Citation2011), not driven by local needs (Roos Citation2019) and merely a short-term solution (Pini et al. Citation2004). Future research might focus on whether the digitalised bioeconomy is to take the same route. We envision research women-only networks and other women-targeted initiatives as part of the digitalisation transformation of the bioeconomy and whether they are effective both for individuals and for the sector as a whole. Linking to the point below we also envision a focus on the effectiveness of men-only activities in the sector such as “#Guytalk”.Footnote2

Third, we propose to include men when researching the intersection of gender, digitalisation and the bioeconomy. With a few exceptions (e.g. recent articles from Abrahamsson and Johansson Citation2020; Bergstén et al. Citation2020) women are in focus when researching gender in relation to digitalisation or the bioeconomy. Including men will not only make the situation better for the men but also for women. Researching men and masculinities means focusing on power relations embedded within the digital transformation of the bioeconomy. We envision studies that, for example, focus on male role models within the sector which could shine light on prevailing and influential ideals of masculinity. Also, the study at hand focuses on the most simple and widely used social categories of gender: men and women. An intersectional approach to gendered relations (i.e. looking into intersections of class, race, and socioeconomic background) in the bioeconomy and digitalisation could extend and deepen our understanding of the underpinnings of gendered practices.

Lastly, we need to take a holistic approach to sustainability within the bioeconomy. We were quite surprised about the absence of environmental sustainability in the bioeconomy/digitalisation dyad. We saw a focus on social implications around a further digitalisation of the bioeconomy (cf. Rotz et al. Citation2019b). However, as we see it social sustainability (with the gender issue include) goes hand in hand with environmental sustainability (Elkington Citation1994). Without a focus on both perspectives a sustainable bioeconomy cannot be achieved. Hence, we argue for a focus on how different sustainability perspectives are used and affected in the bioeconomy.

Our literature review leads us to suggest four points of action for practitioners in the Nordic digitalised bioeconomy: 1) increasing the number of female role models and thereby diversifying the masculine image, creating more inclusiveness. This action may set an example and encourage women to seek education related to the digitalised bioeconomy and find jobs in the area. This alone, however, is not enough to correct gender imbalances, when we recall that the very structures of the bioeconomy and tech industries remain masculine. 2) Mentorship programmes can empower young female graduates to pursue careers in the digitalised bioeconomy. Setting up mentorship programmes entails challenges, however, and must be done following a process of reflective thinking. It important to remember that the aim is not change women to be “better” or “more like men” but rather for men and women to be equals. Critical issues to discuss when organising such a programme would be the sex of the mentors and mentees, how the programmes should be designed, and what the overall focus should be. 3) Networks for young professionals and students in the bioeconomy are valuable for strengthening connections, facilitating discussions and increasing inclusive involvement for students and workers. Peer support is important in succeeding in male dominated industries, where peer support can come from both men and women. 4) Tools and methods must be developed to incorporate this topic into university education related to the bioeconomy. The aim of this action is to facilitate discussion on how gendered structures impact men and women and their opportunities within the area of the digitalised bioeconomy, thereby creating a foundation for change.

Linking these four action points with the envisioned future research, we suggest two considerations that practitioners working with gender in the Nordic digitalised bioeconomy should weigh when taking action. First, when focusing on women-only activities, think of the purpose and structure of the activity. How can this activity benefit both individuals and the level of gender equality in the sector? Second, include men when working with gender issues in the sector. Offer both female role models and gender-conscious male role models. Men should serve both as mentors and mentees. Consider having men-only activities to propel gender equality work within the sector. As we see it, these suggested considerations when taking actions can be used together whenever planning and implementing activities for raising awareness about gender equality as part of the digitalisation of the Nordic bioeconomy sector. If these considerations are combined with the proposed focus for future research, we can expect a more gender-balanced digitalised bioeconomy sector in the future.

Positionality statement

The group of people who have performed this research and written this article comes from different areas and have different competencies. What we all have in common is our interest in and previous focus on gender issues. Together we have theoretical knowledge around forestry, agriculture and gender. Practically we have experience working with gender aware communication, having the responsibility for equal opportunity policies on university-, national and international level, and of university teaching about gender issues within the bioeconomy. We are a group of individuals self-identified as both men and women.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the people who gave us feedback on a draft of this article, namely Triine Rogg Korsvik, Ida Gustafsson, Ida Nordström, Christine Hernblom and Anna Meisner Jensen. Also, we would like to thank NIKK, EIS SNS and NKJ for making this research possible by providing working hours for the authors. This work was partly supported by NIKK – “Nordisk information för kunskap om kön” – within the project “Den digitala bioekonomin – en metodhandbok för en jämställd nordisk bioekonomi”.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 See for example this blogpost on differences and similarities between Web of Science, Google Scholar and Scopus: https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/impactofsocialsciences/2019/12/03/google-scholar-web-of-science-and-scopus-which-is-best-for-me/

References

- Abrahamsson L, Johansson J. 2020. Can new technology challenge macho-masculinities? The case of the mining industry. Mineral Econ.. 34:263–275.

- Acker J. 1990. Hierarchies, jobs, bodies: A theory of gendered organizations. Gend Soc. 4(2):139–158.

- Andersson E, Lidestav G. 2016. Creating alternative spaces and articulating needs: challenging gendered notions of forestry and forest ownership through women's networks. Forest Policy and Economics. 67:38–44.

- Appelstrand M, Lidestav G. 2015. Women entrepreneurship – a shortcut to a more competitive and equal forestry sector? Scand. J. For. Res. 30(3):226–234.

- Bardekjian AC, Nesbitt L, Konijnendijk CC, Lötter BT. 2019. Women in urban forestry and arboriculture: experiences, barriers and strategies for leadership. Urban For. Urban Greening. 46:1–13.

- Baublyte G, Korhonen J, D’Amato D, Toppinen A. 2019. ‘Being one of the boys’: perspectives from female forest industry leaders on gender diversity and the future of Nordic forest-based bioeconomy. Scand. J. For. Res. 34(6):521–528.

- Beliz G, Basco AI, de Azevedo B. 2019. Harnessing the opportunities of inclusive technologies in a global economy. Econ Open-Access, Open-Assessment E-J. 13(2019-6):1–15.

- Bergstén S, Andersson E, Keskitalo ECH. 2020. Same-same but different: Gendering forest ownership in Sweden. For Policy Econ. 115:102–162.

- Boje DM. 2001. Narrative methods for organizational & communication research. London, UK: Sage.

- Bracco S, Calicioglu O, Gomez San Juan M, Flammini A. 2018. Assessing the contribution of bioeconomy to the total economy: A review of national frameworks. Sustainability. 10(6):1698.

- Brandth B, Haugen MS. 2010. Doing farm tourism: The intertwining practices of gender and work. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society. 35(2):425–446.

- Brussevich M, Dabla-Norris ME, Kamunge C, Karnane P, Khalid S, Kochhar MK. 2018. Gender, technology, and the future of work. International Monetary Fund (IMF) staff discussion notes (2018). Accessed 2 December 2020. https://www.imf.org/~/media/Files/Publications/SDN/2018/SDN1807.ashx.

- Czarniawska B. 1998. A narrative approach to organization studies0Qualitative research methods; 43. London, UK: SAGE.

- De Vuyst S. 2018. Cracking the coding ceiling: looking at gender construction in data journalism from a field theory perspective. J Appl J Media Stud. 7(2):387–405.

- De Vuyst S, Raeymaeckers K. 2019. Is journalism gender e-qual? Digital Journalism. 7(5):554–570.

- Durbin S. 2011. Creating knowledge through networks: A gender perspective. Gender, Work & Organ. 18(1):90–112.

- Elkington J. 1994. Towards the sustainable corporation: Win-win-win business strategies for sustainable development. Calif Manage Rev. 36(2):90–100.

- Filyushkina A, Strange N, Löf M, Ezebilo EE, Boman M. 2016. Non-market forest ecosystem services and decision support in Nordic countries. Scand. J. For. Res. 31(1):99–110.

- Finger R, Swinton SM, El Benni N, Walter A. 2019. Precision farming at the nexus of agricultural production and the environment. Annu Rev Resour Economics. 11(1):313–335.

- Follo G, Lidestav G, Ludvig A, Vilkriste L, Hujala T, Karppinen H, Didolot F, Mizaraite D. 2017. Gender in European forest ownership and management: reflections on women as ‘New forest owners’. Scand. J. For. Res. 32(2):174–184.

- Frank H, Hatak I. 2014. Doing a research literature review. In: Fayolle A., Wright M, editors. How to Get published in the best entrepreneurship journals. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing; p. 94–117.

- Franken S, Schenk J, Wattenberg M. 2018. Gender-specific attitudes and competences of young professionals in the context of digitalization. In Proceedings of the 4th Conference on Gender IT. Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 139–141.

- Grubbström A, Powell S. 2020. Persistent norms and the #MeToo effect in Swedish forestry education. Scand. J. For. Res. 35(5–6):308–318.

- Hansen E, Conroy K, Toppinen A, Bull L, Kutnar A, Panwar R. 2016. Does gender diversity in forest sector companies matter? Can J For Res. 46(11):1255–1263.

- Hasenheit M, Gerdes H, Kiresiewa Z, Beekman V. 2016. Summary report on the social, economic and environmental of the bioeconomy. Accessed 24 November 2020. https://www.ecologic.eu/sites/files/publication/2016/2801-social-economic-environmental- impacts-bioeconomy-del2-2.pdf.

- Heggem R. 2014. Exclusion and inclusion of women in Norwegian agriculture: Exploring different outcomes of the ‘tractor gene’. J Rural Stud. 34:263–271.

- Holmgren S, Arora-Jonsson S. 2015. The Forest Kingdom – with what values for the world? Climate change and gender equality in a contested forest policy context. Scand. J. For. Res. 30(3):235–245.

- Holmström J. 2020. Digital Transformation of the Swedish Forestry Value chain: Key Bottlenecks and Pathways Forward. Accessed: 24 November 2020. https://wwwmistradigital.cdn.triggerfish.cloud/uploads/2020/04/jh-wp0-digital-transformation-of-the-swedish-forestry-value-chain.pdf.

- Ingram J, Maye D. 2020. What are the implications of digitalisation for agricultural knowledge? Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems. 4(66):1–6.

- Johansson J, Asztalos Morell I, Lindell E. 2020. Gendering the digitalized metal industry. Gender, Work & Organ. 27(6):1321–1345.

- Johansson K, Andersson E, Johansson M, Lidestav G. 2020. Conditioned openings and restraints: The meaning-making of women professionals breaking into the male-dominated sector of forestry. Gender, Work & Organ. 27(6):927–943.

- Johansson M, Johansson K, Andersson E. 2018. #Metoo in the Swedish forest sector: testimonies from harassed women on sexualised forms of male control. Scand. J. For. Res. 33(5):419–425.

- Johansson M, Ringblom L. 2017. The business case of gender equality in Swedish forestry and mining— restricting or enabling organizational change. Gender, Work & Organ. 24(6):628–642.

- Klitkou A, Bozell J, Panoutsou C, Kuhndt M, Kuusisaari J, Beckmann JP. 2017. Bioeconomy and digitalisation. Accessed: 24 November 2020. http://hdl.handle.net/11250/2612970.

- Knierim A, Kernecker M, Erdle K, Kraus T, Borges F, Wurbs A. 2019. Smart farming technology innovations – Insights and reflections from the German Smart-AKIS hub. NJAS-Wageningen Journal of Life Sciences. 90-91:1–10.

- Korsvik TR, Hulthin M, Sæbø A. 2020. Hva vet vi om kunstig intelligens og likestilling? En kartlegging av norsk forskning [What do we know about artificial intelligence and gender equality? A survey of Norwegian research]. Kilden kjønnsforskning.no.

- Koskivaara E, Somerkoski B. 2020. Alumni reflections on gender equality in the ICT context. In Conference on e-Business, e-Services and e-Society (pp. 380-386). Springer, Cham.

- Krieger-Boden C, Sorgner A. 2018. Labor market opportunities for women in the digital age. Economics Discussion Papers, (2018–28): 1–8.

- Krzywdzinski M, Juergens U, Pfeiffer S. 2016. The Fourth Revolution: The Transformation of Manufacturing Work in the Age of Digitalization. WZB Report. 2016.

- Larasatie P, Barnett T, Hansen E. 2020. Leading with the heart and/or the head? Experiences of women student leaders in top world forestry universities. Scand. J. For. Res. 35(8):588–599.

- Larasatie P, Baublyte G, Conroy K, Hansen E, Toppinen A. 2019. ‘From nude calendars to tractor calendars’: The perspectives of female executives on gender aspects in the North American and Nordic forest industries. Can J For Res. 49(8):915–924.

- Larsson A, Viitaoja Y. 2019. Identifying the digital gender divide: How digitalization may affect the future working conditions for women. In: Larsson A., Teigland R, editors. The digital transformation of labor. New York, NY: Routledge; p. 235–253.

- Lee SB, Kastner S, Walker R. 2015. Mending the Gap, Growing the Pipeline: Increasing Female Representation in Computing, ASEE-SE Annual Conference, Gainsville, FL.

- Lidestav G, Johansson M, Huff ES. 2019. Gender perspectives on forest services in the rise of a bioeconomy discourse. In: Hujala T., Toppinen A., Butler B, editor. Services in Family forestry. Cham: Springer; p. 307–325.

- Linser S, Lier M. 2020. The contribution of sustainable development goals and forest-related indicators to national bioeconomy progress monitoring. Sustainability. 12:2898.

- Lorber J. 1994. Paradoxes of gender. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Martin PY. 2006. Practising gender at work: further thoughts on reflexivity. Gender, Work & Organ. 13(3):254–276.

- Mattila TJ, Judl J, Macombe C, Leskinen P. 2018. Evaluating social sustainability of bioeconomy value chains through integrated use of local and global methods. Biomass Bioenergy. 109:276–283.

- McCormick K, Kautto N. 2013. The bioeconomy in Europe: An overview. Sustainability. 5(6):2589–2608.

- Mozelius, P. 2018. It is getting better, a little better – female application to higher education programmes on Informatics and System science. In proceedings of the International Conference on Gender Research. 2018:249–254.

- Nordic Council of Ministers. 2018. Nordic Bioeconomy Programme: 15 Action Points for Sustainable Change. Accessed 2 December 2020. Available at: http://norden.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1222743/FULLTEXT01.pdf.

- Östlund L, Öbom A, Löfdahl A, Rautio AM. 2020. Women in forestry in the early twentieth century – new opportunities for young women to work and gain their freedom in a traditional agrarian society. Scand. J. For. Res. 35(7):403–416.

- Padovani C, Raeymaeckers K, De Vuyst S. 2019. Transforming the news media. Overcoming old and new gender inequalities. In: Trappel J, editor. Digital media inequalities: policies against divides, distrust and discrimination. Gothenburg: Nordicom; p. 159–177.

- Pechtelidis Y, Kosma Y, Chronaki A. 2015. Between a rock and a hard place: women and computer technology. Gend Educ. 27(2):164–182.

- Peetz D, Murray G. 2019. Women’s employment, segregation and skills in the future of work. Lab Ind. 29(1):132–148.

- Piasna A, Drahokoupil J. 2017. Gender inequalities in the new world of work. Transfer: Eur Rev Lab Res. 23(3):313–332.

- Pini B, Brown K, Ryan C. 2004. Women-only networks as a strategy for change? A case study from local government. Women Manage Rev. 19(6):286–292.

- Pröbster M, Hermann J, Marsden N. 2018. Digital training in tech: a matter of gender? In Proceedings of the 4th Conference on Gender & IT (GenderIT 2018). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 11–18.

- Rajahonka M, Villman K. 2019. Women managers and entrepreneurs and digitalization: on the verge of a new era or a nervous breakdown? Technology Innovation Management Review. 9(6):14–24.

- Refsgaard K, Kull M, Slätmo E, Meijer MW. 2021. Bioeconomy – A driver for regional development in the Nordic countries. New Biotechnol. 60:130–137.

- Regan Á. 2019. ‘Smart farming’ in Ireland: a risk perception study with key governance actors. NJAS- Wageningen J. Life Sci. 90-91(2019):100292.

- Rolandsson B, Alasoini T, Berglund T, Dølvik JE, Hedenus A, Ilsøe A, … Hjelm E. 2020. Digital transformations of traditional work in the Nordic Countries. TemaNord 2020:540. Nordic Council of Ministers.

- Roos A. 2019. Embeddedness in context: understanding gender in a female entrepreneurship network. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development. 31(3–4):279–292.

- Roos A, Gaddefors J. 2017. Innocent sampling in research on gender and entrepreneurship. In: Ratten V., Dana L.-P., Ramadani V, editor. Women entrepreneurship in family business. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

- Rose DC, Wheeler R, Winter M, Lobley M, Chivers CA. 2021. Agriculture 4.0: making it work for people, production, and the planet. Land Use Policy. 100:104933.

- Rotz S, Duncan E, Small M, Botschner J, Dara R, Mosby I, … Fraser ED. 2019a. The politics of digital agricultural technologies: a preliminary review. Sociol Ruralis. 59(2):203–229.

- Rotz S, Gravely E, Mosby I, Duncan E, Finnis E, Horgan M, … Pant L. 2019b. Automated pastures and the digital divide: How agricultural technologies are shaping labour and rural communities. J Rural Stud. 68:112–122.

- Schuster C, Martiny EM. 2016. Not feeling good in STEM: Effects of stereotype activation and anticipated affect on women's career aspirations. Sex Roles. 1(16):40–55.

- Shepherd M, Turner JA, Small B, Wheeler D. 2020. Priorities for science to overcome hurdles thwarting the full promise of the ‘digital agriculture’ revolution. J Sci Food Agric. 100(14):5083–5092.

- SNS Nordic Forest Research. 2020. Gender Balance in the Nordic Forest Sector. Accessed 9 November 2020. https://nordicforestresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/200917-gender-web.pdf.

- Sorama K. 2018. A gender perspective in higher education on megatrends and innovations. ICERI2018 Proceedings. 2018:6157–6167.

- Sorgner A, Bode E, Krieger-Boden C, Aneja U, Coleman S, Mishra V, Robb A. 2017. Effects of digitalization on gender equality in the G20 economies. Accessed 24 November 2020. http://www.w20-germany.org/fileadmin/user_upload/documents/20170714-w20-studie-web.pdf.

- Sorgner A, Krieger-Boden C. 2017. Empowering women in the digital age. G20 Germany. Accessed 24 November 2020. https://www.g20-insights.org/policy_briefs/empowering-women-digital-age/.

- Terrell J, Kofink A, Middleton J, Rainear C, Murphy-Hill E, Parnin C, Stallings J. 2017. Gender differences and bias in open source: Pull request acceptance of women versus men. PeerJ Comp Sci. 3:e111.

- Warmuth AD, GlockentGlockentöger I. 2018. Effects of digitalized and flexible workplaces on parenthood: New concepts in gender relations or a return to traditional gender roles? In: Harteis C, editor. The impact of digitalization in the workplace. Cham: Springer; p. 71–86.

- Watanabe C, Naveed N, Neittaanmäki P. 2019. Digitalized bioeconomy: planned obsolescence- driven circular economy enabled by co-evolutionary coupling. Technol Soc. 56:8–30.

- West C, Zimmerman DH. 1987. Doing gender. Gender Soc. 1(2):125–151.

- Wolfert S, Ge L, Verdouw C, Bogaardt MJ. 2017. Big data in smart farming – a review. Agric Sys. 153:69–80.

1

Documents used in the literature review

No 1-149 are documents from the search. No 150-161 are documents from using tracking method.