Abstract

The widening gap between available resources and increasing possibilities to diagnose and treat different medical conditions has resulted in new attention to priority setting. The issue is complicated and harbours several obstacles because of different valuations concerning the needs of patient groups, the true results (patient benefit) of medical actions, and also important ethical considerations. Earlier attempts have been unsuccessful in introducing a prioritisation milieu into the medical profession, probably due to vague requests for an open and sharp prioritisation process. With a sharpened competition of allocating resources for different medical actions, the medical profession of the cancer sector needs to have a tool for explaining consequences for the different cancer patient groups and what is achieved by the cancer treatments and the care. A model for ranking lists consisting of pairs of patient conditions and medical actions is presented, and the principle for using these lists for priority setting in medical society is discussed.

There is a continuously widening gap between resources and the increasing possibilities to treat different medical conditions. In welfare states, a shift to an ageing population, with greater demands for an active health service, also contributes to higher costs for society Citation[1]. As the results of treatment for common diseases, for example heart failure, are improving, the elderly population is shifting to a demand for higher levels of treatment for other potentially mortal diseases such as cancer. These developments, combined with mostly very high costs of new investigation methods and novel cancer drugs, have resulted in the need for deeper analyses on where resources should be placed, in order to spend the money on the most cost-effective and patient-need orientated treatments and medical care. In this context, economics, politicians, administrators and medical professionals are adopting the word “prioritisation”. If all cost-saving actions, as improvement of efficiency and structural rationalising of the medical care organisation, have been taken into account, and the resources are still lacking, rationing and/or excluding medical services are the next options to guarantee good quantity and quality of “the most important medical care”. This last mentioned term is a very imprecise description of what is expected from the public medical care system and is a matter of opinion and values about the needs and demands from the population Citation[2]. Thus, there is a need of consensus between different medical professions, decision-makers and the population which treatment options the tax-financed health organisation should offer. The medical needs of the population, and not the demands from different individual cases, have to be focused on if a democratic health organisation is the principal aim. However, the act of excluding certain patient groups from tax-supported care because of financial reasons, or to deny a treatment option with more or less good results, harbours wide ethical considerations Citation[3]. A well-developed health care is highly ranked by the population as a most important social service for providing the feeling of security. Therefore, discussions on prioritisation settings within the medical disciplines often give birth to many worries.

Seen from the view of the medical care providers, the patients and their spouses, the “healthy person on the street”, and the media professionals, prioritisation is generally focused on the individual patient. Public investigators, health politicians and administrative staff, economics and social society scientists, the process of prioritisation has the focus more on groups of patients. This deviation in interpretation of the word prioritisation is a potential obstacle in the discussions on when, how, and why a priority setting should be adopted. Attitudes to the process of prioritisation among a limited number of politicians, administrators, doctors and the healthy population in Sweden have been studied Citation[4]. This study Citation[4] reported disturbing differences in opinion between the three groups on the matter of how a prioritisation should be done and also of who should have the principal responsibility to do it. By an open and deep discussion between all involved parties most probably the gap of opinions can be reduced.

Statements of priority committees

An attempt to construct priority lists in Oregon, USA Citation[5], was based on a mixture of public consultations and utility-calculations. This list ranked around 700 pairs of conditions and treatments. It was met by hard criticism, among other reasons, because of the partly subjectivity of the valuations of different health conditions and the problem to be interpreted by the individual patient.

The Norwegian health care system has another type of priority list approach based on severity of the disease or injury Citation[6], and was revised ten years later Citation[7]. These documents also described certain basic difficulties in the process of constructing usable priority settings: 1) lack of knowledge, 2) uncertainties about interpretation of the term “patient need”, 3) patients groups are often unsatisfactorily defined, 4) decision-making of prioritisation are often too decentralised, 5) more money does not necessarily improve medical staff competence, and 6) the aims of health care need to be better clarified. The commission delivered a suggestion of ranking different medical conditions and thereby stated what public medical service should-, ought to, might-, or not necessarily need to offer. In a somewhat different way The Swedish National Priorities Commission Citation[8] stated that the prioritisation between different medical conditions and actions in principle should be performed according to strict ethical standards adopted by WHO in 1997 Citation[9]. Highest in rank is the ethical principle of “human dignity”. Secondly, the principle of “need and solidarity”, and thirdly, the principle of prioritisation according to “cost-efficiency” should be considered when comparing different treatment methods on the same medical disorders. The resources should be distributed so that all the patients with greatest needs (e.g. those with conditions which are acutely life-threatening, leading to invalidity and/or shortening of life) but also to those patients with affected autonomy should be put in the first row for medical care. These principles should be relevant irrespective of individual social status, habits and life style. On the other hand, medical care providers should have a responsibility to select treatment options also with respect of cost-effectiveness so that the resources will be shared with as many patients as possible. The principles and statements of The Swedish National Priorities Commission were delivered to all the different parts in the Swedish medical community. However, although the statements were not openly questioned, the actions of the social organisations and performance of public health care in Sweden did not in practice adapt to the stated principles. Consequently, an investigation was conducted by Socialstyrelsen in 1998 Citation[10] on the application “out in the field” of the priority models of The Swedish National Priorities Commission. In summary, it was found that the principles of prioritisation were adopted only in a very limited sense. Several possible reasons for low activities for prioritisation were listed: 1) the politicians and administrative staff had not created any base for this work, 2) lack of comprehensive strategies and consequent working manner, 3) insufficient knowledge, 4) the potentials of the physicians′ energy was not captured, 5) problems in cooperation between different social organisations, and finally 6) the prioritisation performed needs to be open so all parts understand it. Although these statements are more than 15 years old, all of them are still applicable on the current situation. An additional reason for the historical minimal activities around medical priority settings is that the financial situation in the Swedish (and most other developed countries′) medical society was considered to be stable and expansive until the past few years Citation[1]. In times of good finances there were no obvious incitements for systematic work towards a health care system fully adjusted to the principles suggested by the Swedish authorities.

Irrespective of presence or absence of functioning strategies for prioritisation, all decision-making in the health service have to deal with the matter of prioritisation between patient groups and treatment options. Some patient groups will have their needs well covered while others have to wait for treatment or totally be rejected from medical attention. This has often been called “hidden prioritisation” because the decision makers did not openly express the factors affecting the ranking of patient groups and/or treatment options. These types of selection are often obvious for the caregivers but can be difficult to understand for medically untrained persons, like politicians and administrative staff, even if they are responsible for the financing of the public health care system. The societies demand for more understandable and transparent priority principles has been actualised concomitantly with the increasing gap between the current treatment possibilities versus the resources available. This openness is expected to aim at a system that will secure the consensus that health care primarily should be provided the patient groups with most pronounced medical needs.

Do principles of prioritisation apply on cancer treatment and care?

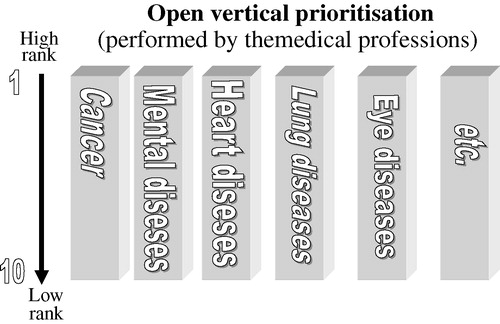

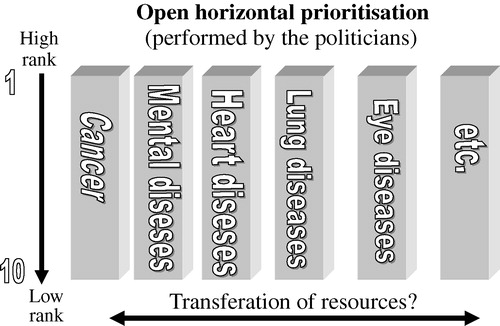

According to the statements of the different priorities committees mentioned above, the conditions of cancer treatment and care in all sense should have highest priority along with handling with other acutely life-threatening situations. Cancer treatment can save or prolong life, hinder handicap and reduce the loss of autonomy, but also give important relief in the late phase of an incurable disease. All these conditions and medical actions are considered to have highest priority in the society whoever is asked. On the other hand, different cancer conditions and treatment actions have dissimilar priority if ranking them within the specific frame of cancer. During the process of cancer diseases the patients needs of medical actions vary. In order to use treatment resources, medical staff time and attention optimally, some type of prioritisation is necessary to perform. An alternative, but not realistic, way to look at this issue would be to claim that firstly all resources should be put on cancer treatment and other highly prioritised actions, and only (if there still are recourses left) other lower prioritised medical care can be provided. This would not be an acceptable generalised principle for the society in allocating resources to the various sectors of health care. Thus, there is a need to find principles of prioritisation, which openly and understandably allows the medical profession to explain and compare the results, costs, risks, evidence, etc of different medical actions in defined patient groups. To construct ranking lists within specific diagnose groups or specialities, such as ophthalmology, psychiatry, cancer, etc, can give a platform for a prioritisation model within a certain speciality. This process has been called “vertical prioritisation” (). A comparison between these ranking lists containing constellations (pairs) of conditions and medical actions, leads to another process, which has been called “horizontal prioritisation (). The borderline between “vertical” and “horizontal” prioritisation is not sharp. However, these two different terms can be adopted in order to simplify the theoretical model. It is describing the vertical component of prioritisation as a matter for the medical profession and the horizontal component more a task for medical administrative decision makers, influenced by interests of the citizens and their elected politicians.

A suggested general framework for ranking lists for cancer

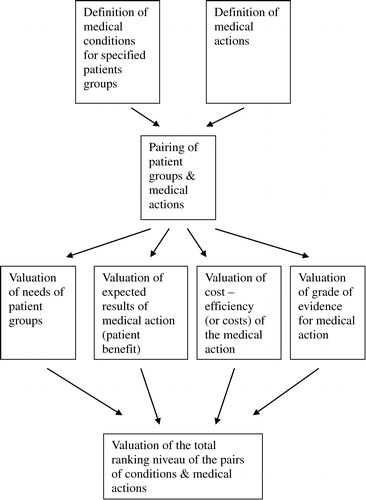

The initial step of constructing ranking lists is to define the different parameters that affect the final rank of each pair of medical conditions and treatment/actions ().

A. The total medical needs of different patients groups are influenced by several well-known components of risks and threats. Examples are risk of death, permanent disease/damage, worsening of quality of life, long lasting suffering, reduced physical mental function, and of an affected autonomy in general. These parameters give a base for ranking how urgent and necessary it is to take care of the specified patient group. If patient needs, with all their components, would be the only factor to focus on, every single cancer patient group should have the highest rank to have some type of attention. Therefore, constellations/pairs of medical conditions coupled with specified treatment actions are a more useful approach for a priority setting also in cancer treatment and care.

B. A second parameter to estimate is the expected “patient benefit” of the treatment action. This will be the sum of expected treatment results for the patient group. For patient groups with cancer, the expected results of medical actions can be separated into: 1) chance for cure (e.g. durable complete remission rate), 2) chance for life prolongation (e.g. median survival prolongation), 3) chance for physical symptom relief (e.g. physical QoL improvement), 4) chance for improvement of the psycho-social status (e.g. psycho-social QoL improvement), and 5) risk with the treatment action (e.g. rate of toxicity or serious adverse advents). In well-defined cancer patients groups and treatment actions, which have been focused on in scientific medical trials, those parameters can easily be provided. However, even if this is the case more frequently in oncology compared to other specialities, numerous cancer treatment actions do not have such well-known results. In regard to contact with cancer patients, the arguments for suggesting or not suggesting an operation, a medical treatment, or other actions of therapy and care, are based on the physician's knowledge or estimations of the expected “patient benefit”. These expressed estimations are more or less influenced by the individual physician's valuations. Expressions like “a good chance for cure”, “some will have pain relief”, “a few will benefit”, “small risk for adverse events” are delivered daily to the cancer patient in order to explain the suggested treatment decision. A way to overcome the individual way to express “patient benefit” is to settle a quantification system for different results. A suggestion for a more homogenised expression of benefit-steps for cure and symptom relief follows: “Good chance”: >75% are expected to be cured or have symptom relief, “Relatively good chance”: 30–75% of patients…, “Relatively small chance”: 10–29% of patients…, “Small chance”: 1–9% of patients.., “No chance for cure”: 0%.

A similar way to grade the estimated degree of life prolongation might be: : “High degree”: >5 years life prolongation “Relatively high degree”: 1–5 years… “Relatively low degree”: 4–11 months… “Low degree”: 1–3 months… “No or insignificant degree”: <1 month of life prolongation. : The expressed degree of risks by the treatment action can be based on WHO-nomenclature for toxicity, surgery mortality/morbidity etc.

The expression of the degree of psycho-social improvement by the medical action has also a diffuse character. This parameter of patient-benefit ranges from low degree (=no attempt to improvement) to high degree (=total holistic approach including 24-hour/day supports of the patients and their spouses, like in a hospice setting).

The suggested way of setting steps of parameters for patient-benefit are not emerging from any scientific ground, but reflects a consensus from several cancer-treatment teams of a Swedish county (Östergötland) and is mentioned here only in order to illustrate an alternative way to standardise the valuations of different degrees of patient benefit, separated in the steps mentioned above.

C: A third component of a ranking list is the parameter cost-effectiveness of the treatment actions for the specified groups of medical condition. Ideally, all resources put on medical actions should be possible to assess in terms of, for example, costs per quality of life-adjusted years saved by the treatment Citation[11]. However, only a minority of medical actions, including cancer treatments and care, have been scrutinised by a professional health economy analysis and should primarily be used Citation[12], Citation[13]. Thus, this parameter often has a vague base for estimation and needs to be simplified in order to provide information of how the costs are balanced between the different constellations of medical conditions/actions. In practice a simplified way to declare the costs could be: “High costs”: >500 000 SEK “Medium costs”: 100 000–499 000 SEK “Low costs”: <100 000 SEK :

D. A fourth parameter in ranking a specified medical condition/action is the degree of evidence for the results according to a systematic scoring, e.g. as recently done by the Swedish Council on Technology Assessment in Health Care (SBU) Citation[14]. Consequently, two medical actions with similar patient-benefits and costs can be ranked differently because of different degree of evidence.

Dilemmas and possibilities in the process of constructing ranking lists according to the above described principles

The medical profession has the main role in assessing the parameters building up a ranking list for prioritisation. Although a straightened up procedure is used, like the one described above, there is a certain space for personal opinion of the factor “patient need”. By strictly following the ethical “principles of human dignity” and of “principle of need and solidarity”, different individuals in the medical profession should not risk to deviate too far from each other. As the substance of the word “need” is not possible to fully define, despite several theoretical attempts Citation[15], this has to be settled by a dialogue between the population and the medical treatment providers.

Another dilemma – mostly for the physician with close patient contacts – is to manage to shift the concept of thinking of prioritisation from the single patient to a defined group of patients. Ideally all patients can be identified in a defined group of medical needs, but the variety of personal needs and demands will never make this possible. One way to meet this dilemma is to look upon a cancer prioritisation setting more as a support for the physician to select the most suitable alternative of action in order to help the patient and not only a way to exclude treatment options.

Another concern is how to deal with pairs of medical conditions and actions with uncertainty about data for evidence and cost-effectiveness. Neither of the two factors will have the most important impact on the level in the ranking list, but the need for more knowledge can be stimulation for further research on those specific vague issues. Also low ranked pairs of condition/action, which have been routine, need more attention to improve the degree of evidence and the knowledge about cost-effectiveness.

The experience from cancer ranking lists according to the here-described method is so far limited. The County of Östergötland, Sweden adopted the strategy two years ago. Already the process of constructing the lists of the pairs of medical conditions/treatment actions in cancer (>350 in the first attempt) both for surgery and non-operative oncology turned out to increase the dialogue between different leading specialists. The essential legitimacy for developing the ranking lists by this method was thereby assured. Also an insight and awareness of the complexity of decision-making has been evoked and eased up the dialogue with people in general, politicians and other decision makers. The ranking list for cancer, although immature and incomplete at this initial stage (see ), was shown to be useful in the process of expressing the internal work and the ultimate results (=patient-benefits) of the medical departments. It is of extreme importance, however, that the lists are accompanied by the medical profession's guidance and consequence analyses in the dialogue about prioritisation with medically non-trained persons.

Table I. Examples from a simplified ranking list consisting of pairs of conditions & medical actions in cancer

Future directions in prioritisation in cancer

The principles of prioritisation need to be uniformly adopted in a national – or even better international-perspective. In Sweden, the Socialstyrelsen is currently producing National Guidelines for colorectal-, breast-, and prostate cancer according to a model with great similarities to the above described. These guidelines are expected to be the base for the future regional prioritisation processes along with further attempts within the Swedish Society of Oncology to standardise the prioritisation concept for all cancer treatments and care.

Conclusions

The cancer treatment profession has to take an active part in the open priority process both for internal and for inter-speciality considerations. Thereby, it is better to highlight what can be considered to be necessary, safe, cost-effective, and evidence-based routine medical care. A widely adopted ranking list with pairs of conditions and treatments, covering all phases of cancer disease, will be an useful tool in a more structured open dialogue and how to allocate needed financial and personnel resources.

This paper is based upon a Keynote Lecture, and follow-up discussion, presented at the Swedish Society of Oncology meeting in Umeå, March 2003 and during a symposium about priority settings in cancer care at the meeting in Stockholm, March 2005.

References

- www.irdes.fr/ecosante/OCDE/411010.html.

- McCloskey RP. Human need, rights and political values. American Philosophical Quarterly 1976; 13: 1–11

- Daniels N, Sabin JE. Limits to health care: fair procedures, democratic deliberation and the legitimacy problem for insurers. Philosophy and Public Policy Affairs 1997; 26: 303–50

- Rosén, P.Attitudes to prioritisation in health services. Nordic School & Public Health, Gothenburg 2002, (NHV-report 2002:1).

- Ham C. Priority setting in health care: learning from international experience. Health Policy 1997; 42: 49–66

- Socialdepartementet, Oslo. Guiding principles for priorities in Norwegian health services. NOU. 1987:23. (In Norwegian).

- Social-og Helsedepartementet, Oslo. New priorities. NOU. 1997:18. (In Norwegian).

- The Swedish Parliamentary Priorities Commission (1995) . Priorities in health care. Ethics, economy implementation. Socialdepartementet; 1995. Report No.: SOU:5.

- WHO Regional Office for Europe, Copenhagen. Analysis of current strategies, WHO, European Health Care Reform. 1997, R Saltzman, Figueras, J, editors.

- Socialstyrelsen, Stockholm. Priorities in Medical Treatment, decisions and applications. Report No.: SoS. 1999:16. (In Swedish).

- Maynard A. Developing the health care market. Econ J 1991; 101: 1277–86

- Karlsson G, Nygren P, Glimelius B. Economic aspects of chemotherapy. Acta Oncol 2001; 40(2–3)412–33

- Norlund A. Costs of radiotherapy. Acta Oncol 2003; 42(5–6)411–5

- Glimelius B, Bergh J, Brandt L, Brorsson B, Gunnars B, Hafström L, et al. The Swedish Council on Technology Assessment in Health Care (SBU) systematic overview of chemotherapy effects in some major tumour types–summary and conclusions. Acta Oncol 2001; 40(2–3)135–54

- Liss PE. Health Care Need. Aldershot, Avebury. 1993