Abstract

Up to 90% of patients with localized non-Hodgkin's lymphomas (NHL) in the gastrointestinal tract (GI) are cured and decreased use of radical surgery is favoured. Although quality of life (QOL) may impact treatment choice, little is known about QOL in gastric NHL survivors. The self-reported QOL (EORTC QLQ-C30 and a gastric module) and objective findings from upper GI endoscopy were evaluated in patients in complete remission after treatment for primary gastric NHL at the Norwegian Radium Hospital (NRH). Thirty-six (90%) patients completed the questionnaires, 33 (83%) met for endoscopy. Ten patients were treated with total gastrectomy, 17 with partial gastrectomy, while nine patients did not undergo surgery. Gastroscopy was normal in 55% of the non-gastrectomised patients, oesophagoscopy in 69%. Four patients had Barrett's metaplasia. QOL was not different from population values. Patients treated with total gastrectomy reported poorer emotional function, more diarrhoea and more food-related problems (p ≤ 0.05) compared with the others. Based on the higher level of digestive and food related problems after total gastrectomy, stomach-preserving surgery should be preferred whenever possible.

The gastrointestinal tract (GI) is the most common site of primary extra-nodal non-Hodgkin's lymphomas (NHL), accounting for 30 to 40% of cases and about 12% of all NHL. The stomach is the most common localization of NHL in the GI tract Citation[1]. According to the literature, there is still no consensus regarding the appropriate diagnostic and therapeutic regimen for primary gastric B-cell lymphomas, primarily due to a variety of classifications, numerous protocols and a paucity of prospective trials Citation[2]. Recent reviews favour approaches without surgery Citation[3], Citation[4], due to smaller risk of perforation of the gastric wall than previously believed Citation[5], Citation[6], the apparent successful treatment directed towards Helicobacter pylori in marginal zone B-cell lymphomas Citation[5], Citation[7] and due to concerns about the long term side effects after radical surgery with respect to digestion, nutritional status, metabolism and physical and psychosocial functioning Citation[8], Citation[9].

Results from studies evaluating quality of life (QOL) after total or partial gastrectomy in gastric cancer are not consistent Citation[10–17], but the weight of evidence supports less radical surgery whenever possible Citation[10], Citation[11], Citation[14], Citation[16], Citation[17], primarily due to fewer treatment related side effects and digestive problems.

In contrast to the case in adenocarcinomas, stomach preserving treatment is an alternative treatment in gastric lymphomas with a comparable survival in both localized Citation[5], Citation[18], Citation[19] and advanced stages Citation[20]. Less use of surgery implies increased use of chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Thus, a systematic evaluation of the prevalence and severity of treatment related side effects is important in treatment selection.

We were able to identify only two reports on QOL in patients with GI lymphomas Citation[2], Citation[21], one emphasizing the need for randomized trials including QOL Citation[2], the other recommending a conservative approach in stages IE and IIE, claiming good QOL, although not assessed by a validated instrument Citation[21]. Thus, little is known about the impact of treatment modality on QOL of these patients.

Due to the paucity of studies, we designed a Norwegian cross-sectional study, which to our knowledge is the first report that specifically focuses on QOL after treatment for primary gastric lymphoma. The major objective was to compare the QOL of patients treated at the Norwegian Radium Hospital (NRH) with reference values from the general population. We also performed comparisons across treatment groups to shed light on our underlying hypothesis based on clinical experience: that those who were treated with total gastrectomy experienced a higher level of treatment related problems than those receiving other treatment modalities, including partial gastrectomy, by the use of a validated, treatment specific questionnaire for gastro-intestinal problems. The histological diagnoses were reviewed according to the WHO classification Citation[22] and macroscopic and histological findings from upper GI endoscopy were evaluated.

Methods

Patients

Patient data and relevant clinical variables were obtained from the lymphoma database at the NRH. Altogether 120 patients with a median age of 63 years (range 17–79) were treated for primary gastric non-Burkitt B-cell lymphoma from 1990 through 1999 according to a standard protocol: Primary surgery was recommended in operable patients with high grade lymphomas according to the Kiel classification Citation[23], stages IE and IIE and in stages IIE extended to IV with deep invasion into the gastric wall, when technically feasible Citation[24]. Surgery was supplemented with three (stages IE–IIE localized) to eight (stages IIE extended–IV) cycles of the CHOP regimen (Cyclophosphamide, Doxorubicin, Vincristine, Prednisone). In stages IE–IIE with non-radical surgery, radiotherapy (40 Gy in 20 fractions) was also given in cases of residual disease after chemotherapy. For patients with indolent localized lymphomas, surgery was confined to cases without widespread mucosal infiltration and supplemented with radiotherapy when surgery was considered non-radical. Non-surgically treated patients received local radiotherapy for stages IE–IIE localized, chlorambucil chemotherapy for stages IIE–IVE, or no initial therapy if without clinical symptoms.

Only 33% of the patients had localized disease (stage IE–IIE). Seventy-nine patients had histologically primary aggressive B-cell lymphomas or aggressive B-cell lymphomas transformed from MALT-lymphomas (marginal zone B-cell lymphomas according to WHO classification) Citation[22] and 41 patients had indolent lymphomas, in most cases marginal zone B-cell lymphomas. Thirty-one of 40 patients (78%) with localized disease underwent gastric surgery as part of the initial treatment compared with 30 of 80 patients (38%) with disseminated disease. Twenty-nine patients were treated with total gastrectomy, while 32 patients received a partial gastrectomy. There was no difference in the rate of surgery between patients below (49%) or above 70 years (52%).

The inclusion criteria encompassed a verified histological diagnosis of gastric NHL, established and treated from 1990 through 1999, age above 16 years and below 80 years at the start of treatment, age below 80 years and in complete remission at follow up, no prior history of cancer, fluency in oral and written Norwegian and written informed consent.

A total of 40 patients were identified. All patients were contacted by mail and received an invitation for a medical follow-up at the NRH, the QOL questionnaires, written study information and a prepaid return envelope. The medical follow-up included upper GI endoscopy with biopsies for histological examinations, a general clinical examination and anthropometric measures. The body mass index (BMI) was calculated (weight in kilos divided by the square height in meter), as an indicator of nutritional status. A BMI below 20 was regarded as underweight.

The study was approved by the Regional Committee for Medical Research Ethics, Health Region I, Norway and The Institutional Review Board at the NRH.

Pathology

Hematoxylin/eosin (H&E) as well as immunohistochemically-stained sections from the diagnostic material from all included patients were reviewed by two experienced hematopathologists, and the diagnoses were made according to the WHO classification Citation[22] (). Diagnoses included diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and extra-nodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma with or without increased number of large cells.

Table I. Characteristics of study population.

The EORTC QLQ-C30 and the gastric module STO22

The EORTC QLQ-C30, version 3, was developed by the EORTC Quality of Life Study Group Citation[25]. It has been validated and cross-culturally tested in various cancer populations. The 30-item questionnaire is composed of scales evaluating physical, role, emotional, cognitive and social function, and global quality of life. Three symptom scales evaluate nausea and vomiting, pain and fatigue, while six single items assess financial difficulties, dyspnoea, diarrhoea, appetite loss, sleep disturbances and constipation. The response categories are with four categories: “not at all”, “a little”, “quite a bit” or “very much” or as a modified visual analogue scale going from 1 to 7. It is recommended that the EORTC QLQ-C30 core questionnaire is supplemented by cancer or treatment specific modules Citation[25].

The STO22, a stomach specific module was developed by the QOL Study Group for assessment of QOL for gastric cancer Citation[26] and focuses specifically on symptoms and side effects related to gastric cancer. It encompasses 22 items that form five scales (dysphagia, pain and discomfort in the abdominal area, dietary restrictions, upper gastro-intestinal symptoms and specific emotional problems) and four single items (dry mouth, two questions regarding hair loss and body image). All items have the same four answer categories as the EORTC QLQ-C30.

All scores of the questionnaires were linearly transformed to a 0 to 100 scale. Higher scores on the functional scales and the global quality of life (QOL) scale of the core questionnaire represent better functioning, while higher scores on the symptom scales and single items and all questions of the STO22 indicate more symptoms or problems.

Population data

Patients’ scores on the EORTC QLQ-C30 were compared against reference values from a Norwegian general population survey Citation[27]. This sample, representative of the adult Norwegian population, was based on a random draw of all inhabitants by The Office of the National Register. A total of 1965 people completed the questionnaires, giving a response rate of 68%. Results from this postal survey yielded representative data on QOL in the total population, also for gender and age subgroups.

Statistical analyses

In accordance with the study objectives, descriptive analyses were used for the different scales and items of the EORTC QLQ-C30 and the module, for the entire patient group and for the treatment subgroup. Missing data were imputed as advocated in the EORTC manual, by substituting the missing item with the mean value of the answered items of the scale, provided that 50% of the items were filled in Citation[28].

Differences across groups were tested with χ2 (nominal categorical variables), Wilcoxon's tests 2-tailed for independent samples, and Kruskal-Wallis analyses of variance where appropriate. Overall survival was defined as death from any cause from the time of diagnosis, and disease specific survival as death from or with lymphoma, and death from complication to treatment. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were estimated for all the patients during the study period. The log-rank test was used to compare the survival curves of the two groups. A p-level of 0.05 or less was taken to indicate statistical significance. SPSS, version 10.0 was used for the statistical analyses (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Il, USA).

No gold standard exists regarding the clinically significant numerical changes on scales for QOL data. Differences of 10 point or more on the 0–100 points scales are generally regarded to be clinically significant changes and perceptible to patients, whereas differences of seven to ten points represent questionable clinical importance Citation[27], Citation[29].

Normative reference values have been collected for most of the better-known HRQL instruments, such as the SF36 Citation[30]. It is generally not appropriate however, to compare directly the QOL scores of people with health problems against reference scores from a general population sample, mainly because QOL tends to vary with age and gender Citation[27], Citation[30]. Thus, allowance has to be made for the age/gender distribution in the target sample. In this study, adjustments were made by standard epidemiological methods, described in detail previously Citation[31].

Results

Patients

Thirty-six (90%) of 40 eligible patients completed the QOL questionnaires, while 33 met for the clinical examination. Two patients could not be traced and one was hospitalized due to other conditions. One patient who was significantly younger than the rest of the sample and who did not meet for the clinical examination, presented outlying and highly inconsistent values on most QOL scales and items, and was not included.

The age range of the patients was 47–79 (median 67) at follow-up. Median observation time since initial treatment was 107 months (34–148) (). Seventy-one percent of the patients were married, and the majority (70%) were on sick-leave or retirement or disability pension.

The most prevalent diagnosis (47%) was primary diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) after revision of histology. Ten patients (28%) underwent total gastrectomy, followed by a reconstruction ad modum Roux-en-Y. Eight patients received no gastric surgery. One patient had minor surgery only in the distal duodenum. As this was highly unlikely to impact on long-term QOL and GI symptoms, he was included in the no-surgery group (n = 9), .

No significant differences in age, gender, relapse or performance status at follow-up were found across treatment groups. The complication rates were low. One patient experienced intra-abdominal complications in terms of infection and a pancreatico-jejuno-cutaneous fistula and underwent surgical repair, while one patient had a postoperative lung embolus that was successfully treated.

Supplementary therapy was given to 22 of the surgically treated patients, including the one who underwent minor surgery only (n = 27). Three to eight courses of the CHOP (Cyclophosphamide, Doxorubicin, Vincristine, Prednisone) regimen was most frequently administered (). Five of those who had no gastric surgery received chemotherapy with CHOP and two received radiotherapy, one subsequent to chemotherapy. One patient was treated with high-dose chemotherapy and stem cell transplantation after a minor resection of the distal duodenum, while one patient was observed and received chemotherapy at clinical progression.

Seven of those treated with total gastrectomy had lost weight during follow-up. Their median BMI at follow-up was significantly lower than in the other two groups (p = 0.004), being 23 (range 17–28) before surgery and 19.5 (17–25) at follow-up. This was in contrast to stable values in those treated with partial gastrectomy (23 and 24) and the increase in the group with no surgery (from 20 to 25, p = 0.03).

Upper GI – endoscopy

Oesophagoscopy was performed in 29 patients (three were on anti-coagulation therapy and one patient declined). The macroscopic findings were normal in 69% of the procedures (). Barrett's metaplasia was found in two patients. While 75% of the biopsies yielded normal results on histological examination, another two patients with Barrett's metaplasia without dysplasia were thus identified, in addition to three patients having oesophagitis. Three of the patients with Barrett's metaplasia had been treated with partial gastrectomy, (Billroth I and II, n = 2 and ventricular resection, n = 1) as primary treatment for their lymphomas, while one had received chemotherapy only as the primary treatment. None of these patients had been treated with radiation therapy. When examining the charts of the patients with Barrett's metaplasia, no differences in smoking habits were found compared with the other patients. The majority of the gastroscopies (55%) also yielded normal results (). No malignancies were found.

Table II. Results from oesophagoscopy and gastroscopy.

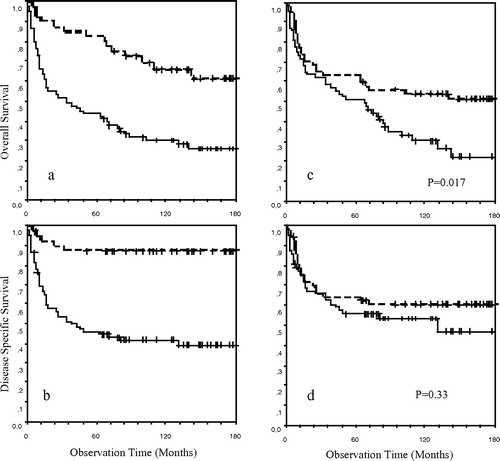

A survival analysis for the entire cohort of patients with gastric lymphoma during the study period was performed to describe the representativity of the material. There was no difference in stage distribution and histological subgroups between the younger and the older population. As the population is older than in most clinical studies, we present both the disease specific and overall survival for patients with localized and disseminated disease and for patients below and above the median age of 63 years (a–1d).

Figure 1. (a and b) Overall and disease specific survival respectively in patients with stage IE and IIE disease (n = 40) and with stage IV disease (n = 80); (c and d) Overall and disease specific survival respectively in patients below the median age of 63 years (n = 60) and above 63 years (n = 60).

Quality of life

Ninety percent of the eligible patients (36/40) completed the questionnaires with few missing items, only 0.06%. There were only minor differences between the patient sample and the general population on the functional scales of the QLQ–C30. No statistically significant differences were reached when comparing the patients’ mean values of the symptom scales and single items with population scores. However, higher mean scores within the range of a probable clinical significance were reported by the patients with diarrhoea and loss of appetite (17 vs. 10, and 14 vs. 7 respectively).

The patients were divided according to type of primary treatment: total gastrectomy, n = 10, partial gastrectomy, n = 17 and no gastric surgery, n = 9 (). Those who had received a total gastrectomy generally had lower mean scores on the functional scales and higher mean scores on the symptoms/single items, indicating more problems. Emotional function was the only scale being statistically significant across groups, being worse in the total gastrectomy group compared with the partial gastrectomy group (70 vs. 88, p = 0.05). Diarrhoea was significantly more frequent after total than after partial gastrectomy (33 vs. 8, p.=0.02). Differences exceeding 10, in the direction of poorer functional levels or more symptomatology after total gastrectomy compared with the other two groups were found with social function (72 vs. 88) and fatigue (37 vs. 27) without reaching statistical significance.

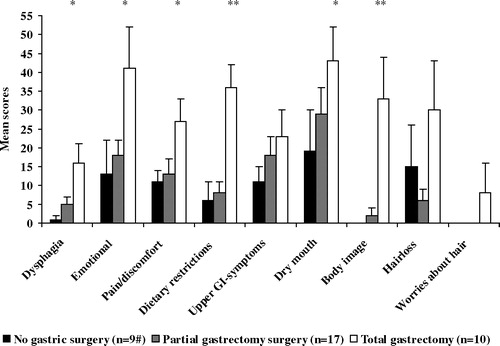

Treatment specific symptoms

Treatment specific symptoms showed a trend similar to the QOL scores (). The total gastrectomy group reported more problems on all scales/item, with statistically significant differences for dietary restrictions and altered body image compared with the other two groups (p values 0.008– < 0.05). Dysphagia (16 vs 1, p < 0.05), pain/discomfort in the abdominal area, emotional problems and dry mouth were also more frequent after total gastrectomy compared with those who were not treated with surgery (p < 0.05).

Figure 2. Treatment specific module, STO221, across treatment groups. 1 Higher scores indicate more symptoms. * p-value<.05, total gastrectomy group vs. partial gastrectomy group. ** p-value≤.05, total gastrectomy group vs. both other groups. # including one patient who underwent minor duodenal resection only.

A frequency distribution of the answer categories on the different items displays the prevalence of the reported problems. Seventeen percent of the patients had “quite a bit” or “very much” problems on the question about early satiety. Nineteen percent said that they were “quite a bit” or “very much” bothered by acid digestion/heartburn, while the corresponding percentages for dry mouth were 22. Nineteen percent gave the disease “very much” or “quite a bit” of thought and 25% were worried about future health.

Discussion

This report shows that patients who were successfully treated for B-cell lymphoma of the stomach, reported a comparable QOL to that of the general population. However, when dividing the sample into subgroups based on surgery, our clinically derived hypothesis of more treatment related problems after total gastrectomy was confirmed. This is consistent with results from gastric cancer Citation[13], Citation[16].

Because gastric lymphoma is highly curable as opposed to gastric adenocarcinomas, knowledge of post-operative adverse effects and QOL are important to inform the selection of surgical procedure Citation[32], all the more so when different procedures with comparable survival rates have different physical and functional immediate and late consequences. Hence, this report adds to the literature by being the first to address these matters in gastric lymphoma. The relatively long follow-up (median 107 months) is important, because it has been suggested that impaired QOL after total gastrectomy tends to decrease with the passage of time Citation[13], Citation[18], Citation[33].

Treatment outcome in terms of disease specific and overall survival is an important issue when considering QOL in patients possibly cured for their cancer. The treatment results of patients in stage IE–IIE in our study are satisfactory and comparable to other studies in which gastric surgery has been employed as part of the primary treatment in the earlier, but not in the later studies Citation[7], Citation[8], Citation[21]. The use of primary gastric surgery had no obvious effect on survival in any of these studies. We have not examined the effect of surgery and type of surgical intervention on survival as the disease stage, histology and performance status differed between these small subgroups of therapeutic intervention. Because the disease specific survival was comparable between the younger and older patients, therapy with curative intent should also be given to elderly patients if their general condition is satisfactory.

The use of a validated, cancer specific QOL questionnaire with general population values and the STO22 module provides valid, clinically relevant data after gastric surgery. Although the EORTC QLQ-C30 is widely employed, we were only able to identify three reports of its use after total or partial gastrectomy in gastric cancer Citation[14], Citation[33], Citation[34]. The high prevalence of treatment related side effects on the STO22 has implications for clinical practice. This emphasizes the importance of addressing specific symptoms like dumping symptoms, difficulties swallowing, belching and diarrhoea as these may explain the decline in BMI due to inadequate food intake and mal-absorption Citation[35]. Preoperative information about nutrition and symptom management may help patients to effectively control symptoms Citation[35], Citation[36] with a positive impact on QOL.

The majority of the endoscopic findings were normal or without clinical significance. However, Barrett's metaplasia without dysplasia was identified in four patients. Duodeno-gastric reflux after surgery induces an increased risk of gastric and oesophageal carcinomas in rat models and possibly in man Citation[37], Citation[38]. Patients treated with total gastrectomy should be offered regular medical follow-up, and endoscopic examinations should be performed according to clinical guidelines Citation[39]. Patients with Barrett's metaplasia with or without dysplasia should also receive follow-up care according to these same guidelines.

We have presented a cross-sectional study. However, we recognize that a prospective study is the ideal design for evaluation of the impact of radical surgery on adverse effects and QOL. A more rigorous design would have made the needs for specific interventions even more apparent. A major limitation of this study is the small sample size. However, few QOL studies in gastric cancer have samples exceeding 150 patients Citation[12], Citation[16], Citation[19], the majority including 50 patients or fewer Citation[13–15], Citation[33], Citation[40], Citation[41]. Nevertheless, the results presented here provide important information about the QOL after gastrectomy in gastric lymphoma, consistent with reports in gastric cancer.

The literature generally recommends less use of primary, radical surgery in gastric lymphomas. This is particularly so in Helicobacter pylori positive low-grade B-cell lymphomas, stages IE. If surgery is necessary due to bleeding, perforation or localized relapse, stomach-preserving surgery will certainly reduce the treatment related symptoms and improve QOL for some of the patients as supported by the results from this study.

References

- Glass AG, Karnell LH, Menck HR. The National Cancer Data Base report on non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Cancer 1997; 80: 2311–20

- Fischbach W, Dragosics B, Kolve-Goebeler ME, Ohmann C, Greiner A, Yang Q, et al. Primary gastric B-cell lymphoma: Results of a prospective multicenter study. The German-Austrian Gastrointestinal Lymphoma Study Group. Gastroenterology 2000; 119: 1191–202

- Al Akwaa AM, Siddiqui N, Al Mofleh IA. Primary gastric lymphoma. World J Gastroenterol 2004; 10: 5–11

- Yoon SS, Coit DG, Portlock CS, Karpeh MS. The diminishing role of surgery in the treatment of gastric lymphoma. Ann Surg 2004; 240: 28–37

- Koch P, del Valle F, Berdel WE, Willich NA, Reers B, Hiddemann W, et al. Primary gastrointestinal non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: II. Combined surgical and conservative or conservative management only in localized gastric lymphoma–results of the prospective German Multicenter Study GIT NHL 01/92. J Clin Oncol 2001; 19: 3874–83

- Binn M, Ruskone-Fourmestraux A, Lepage E, Haioun C, Delmer A, Aegerter P, et al. Surgical resection plus chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone: Comparison of two strategies to treat diffuse large B-cell gastric lymphoma. Ann Oncol 2003; 14: 1751–7

- Roggero E, Zucca E, Pinotti G, Pascarella A, Capella C, Savio A, et al. Eradication of Helicobacter pylori infection in primary low-grade gastric lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue. Ann Intern Med 1995; 122: 767–9

- Chott A, Dragosics B, Radaszkiewicz T. Peripheral T-cell lymphomas of the intestine. Am J Pathol 1992; 141: 1361–71

- Thieblemont C, Bastion Y, Berger F, Rieux C, Salles G, Dumontel C, et al. Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue gastrointestinal and nongastrointestinal lymphoma behavior: Analysis of 108 patients. J Clin Oncol 1997; 15: 1624–30

- Braga M, Molinari M, Zuliani W, Foppa L, Gianotti L, Radaelli G, et al. Surgical treatment of gastric adenocarcinoma: Impact on survival and quality of life. A prospective ten year study. Hepatogastroenterology 1996; 43: 187–93

- Davies J, Johnston D, Sue-Ling H, Young S, May J, Griffith J, et al. Total or subtotal gastrectomy for gastric carcinoma? A study of quality of life. World J Surg 1998; 22: 1048–55

- Hoksch B, Ablassmaier B, Zieren J, Muller JM. Quality of life after gastrectomy: Longmire's reconstruction alone compared with additional pouch reconstruction. World J Surg 2002; 26: 335–41

- Horvath OP, Kalmar K, Cseke L, Poto L, Zambo K. Nutritional and life – quality consequences of aboral pouch construction after total gastrectomy: A randomized, controlled study. Eur J Surg Oncol 2001; 27: 558–63

- Jentschura D, Winkler M, Strohmeier N, Rumstadt B, Hagmuller E. Quality-of-life after curative surgery for gastric cancer: A comparison between total gastrectomy and subtotal gastric resection. Hepatogastroenterology 1997; 44: 1137–42

- Kalmar K, Cseke L, Zambo K, Horvath OP. Comparison of quality of life and nutritional parameters after total gastrectomy and a new type of pouch construction with simple Roux-en-Y reconstruction: Preliminary results of a prospective, randomized, controlled study. Dig Dis Sci 2001; 46: 1791–6

- Svedlund J, Sullivan M, Liedman B, Lundell L, Sjodin I. Quality of life after gastrectomy for gastric carcinoma: Controlled study of reconstructive procedures. World J Surg 1997; 21: 422–33

- Wu CW, Hsieh MC, Lo SS, Lui WY, P'eng FK. Quality of life of patients with gastric adenocarcinoma after curative gastrectomy. World J Surg 1997; 21: 777–82

- Koch P, del Valle F, Berdel WE, Willich NA, Reers B, Hiddemann W, et al. Primary gastrointestinal non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: I. Anatomic and histologic distribution, clinical features, and survival data of 371 patients registered in the German Multicenter Study GIT NHL 01/92. J Clin Oncol 2001; 19: 3861–73

- Aviles A, Nambo MJ, Neri N, Talavera A, Cleto S. The role of surgery in primary gastric lymphoma: Results of a controlled clinical trial. Ann Surg 2004; 240: 44–50

- Salles G, Herbrecht R, Tilly H, Berger F, Brousse N, Gisselbrecht C, et al. Aggressive primary gastrointestinal lymphomas: Review of 91 patients treated with the LNH-84 regimen. A study of the Groupe d'Etude des Lymphomes Agressifs. Am J Med 1991; 90: 77–84

- Ferreri AJ, Freschi M, Dell'Oro S, Viale E, Villa E, Ponzoni M. Prognostic significance of the histopathologic recognition of low- and high-grade components in stage I–II B-cell gastric lymphomas. Am J Surg Pathol 2001; 25: 95–102

- Jaffe ES, Harris NL, Stein H, Vardiman JW. Tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. Pathology and genetics. WHO classification of tumours. IARC Press, Lyon 2001

- Stansfeld AG, Diebold J, Noel H, Kapanci Y, Rilke R, Kelenyi G, et al. Updated Kiel classification for lymphomas [letter]. Lancet 1988; 8580: 292–3

- Musshoff K. Klinische Stadieneinteilung der nicht-Hodgkin lymphome. Stralenterapie 1977; 153: 575–7

- Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, Bullinger M, Cull A, Duez NJ, et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: A quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst 1993; 85: 365–76

- Vickery CW, Blazeby JM, Conroy T, Arraras J, Sezer O, Koller M, et al. Development of an EORTC disease-specific quality of life module for use in patients with gastric cancer. Eur J Cancer 2001; 37: 966–71

- Hjermstad MJ, Fayers PM, Bjordal K, Kaasa S. Health-related quality of life in the general Norwegian population assessed by the EORTC Core Quality of Life Questionnaire-the QLQ-C30 (+3). J Clin Oncol 1998; 16: 1188–96

- Fayers PM, Aaronson N, Bjordal K, Sullivan M. EORTC QLQ-C30. Scoring manual. EORTC Quality of Life Study Group, Brussels 1995

- Osoba D, Rodrigues G, Myles J, Zee B, Pater J. Interpreting the significance of changes in health-related quality-of-life scores. J Clin Oncol 1998; 16: 139–44

- Sullivan M, Karlsson J, Ware J. The Swedish SF-36 Health Survey-I. Evaluation of data quality, scaling assumptions, reliability and construct validity across general populations in Sweden. Soc Sci Med 1995; 41: 1349–58

- Hjermstad MJ, Fayers PM, Bjordal K, Kaasa S. Using reference data on quality of life-the importance of adjusting for age and gender, exemplified by the EORTC QLQ-C30(+3). Eur J Cancer 1998; 34: 1381–89

- Langenhoff BS, Krabbe PF, Wobbes T, Ruers TJ. Quality of life as an outcome measure in surgical oncology. Br J Surg 2001; 88: 643–52

- Diaz de Liano A, Oteiza Martinez F, Ciga MA, Aizcorbe M, Cobo F, Trujillo R. Impact of surgical procedure for gastric cancer on quality of life. Br J Surg 2003; 90: 91–4

- Thybusch-Bernhardt A, Schmidt C, Kuchler T, Schmid A, Henne-Bruns D, Kremer B. Quality of life following radical surgical treatment of gastric carcinoma. World J Surg 1999; 23: 503–8

- Liedman B, Svedlund J, Sullivan M, Larsson L, Lundell L. Symptom control may improve food intake, body composition, and aspects of quality of life after gastrectomy in cancer patients. Dig Dis Sci 2001; 46: 2673–80

- Ishihara K. Long-term quality of life in patients after total gastrectomy. Cancer Nurs 1999; 22: 220–7

- Fein M, Fuchs KH, Stopper H, Diem S, Herderich M. Duodenogastric reflux and foregut carcinogenesis: analysis of duodenal juice in a rodent model of cancer. Carcinogenesis 2000; 21: 2079–84

- Yamashita Y, Homma K, Kako N, Clark GW, Smyrk TC, Hinder RA, et al. Effect of duodenal components of the refluxate on development of esophageal neoplasia in rats. J Gastrointest Surg 1998; 2: 350–5

- Sampliner RE. Updated guidelines for the diagnosis, surveillance, and therapy of Barrett's esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol 2002; 97: 1888–95

- Metzger J, Degen L, Harder F, von Flüe M. Subjective and functional results after replacement of the stomach with an ileocecal segment: a prospective study of 20 patients. Int J Colorectal Dis 2002; 17: 268–74

- Tomita R, Fujisaki S, Tanjoh K, Fukuzawa M. Relationship between gastroduodenal interdigestive migrating motor complex and quality of life in patients with distal subtotal gastrectomy for early gastric cancer. Int Surg 2000; 85: 113–23