Abstract

Despite presumed curative operation almost one-third of patients with prostatic carcinoma relapse. One obvious reason is that the preoperative lymph node staging is not sufficiently effective. Imaging modalities (CT and NMR) have not resolved the problem. Presently lymphadenectomy is not recommended in patients with Gleason score <7 and PSA <20 ng/ml owing to the low frequency of positive nodes. However, these data are based on experience with limited dissection. Results from extended dissection reveal a higher rate of metastases than previously found. The results from extended dissections showed that more than half of the diagnosed lymph node metastases were found outside the generally recommended regions. The drawback is the higher complication rate that follows. Thus the staging can be improved but if this translates into a survival benefit it needs to be addressed in controlled trials. Alternative techniques for lymph node staging have recently been developed. The sentinel lymph node (SLN) method has been tested and proved feasible. The results corroborated those of extended dissection, namely that the obturator region is insufficient to reflect the field of metastases. High-resolution MRI with magnetic nanoparticles can detect small and otherwise undetectable lymph-node metastases. Positron emission tomography (PET), using acetate or choline as tracers, has performed better than fluoro-2-deoyglucose for detection of relapsing prostate cancer after radical prostatectomy. Studies have also started to assess its role for lymph node staging. In summary, lymph node staging has to cover a larger anatomical field than routinely used. Whether surgical dissection can be replaced by the new imaging modalities is presently under investigation.

There is a high failure rate after intended curative therapy of prostate cancer due to undetected extracapsular growth, hematogenous or lymphogenous metastases. The fact that a decrease in positive surgical margins at prostatectomy after neoadjuvant hormonal treatment does not translate into a survival benefit indicates that the major reason for failure is undiagnosed disseminated disease. Hematogenous dissemination to the bone is common in advanced disease and has received much attention, in particular with regard to the possibility to counteract this phenomenon with bisphosphonates. This review will focus on the diagnosis of lymphogenous metastases, a field that has not received much attention recently. A strong association has been found between nodal status and distant metastases, confirming the nodal status as an important indicator for the metastatic potential Citation[1]. The issues discussed in this review are: When is lymph node staging indicated? How should it be performed? What are the possible new developments in this field?

Anatomical considerations

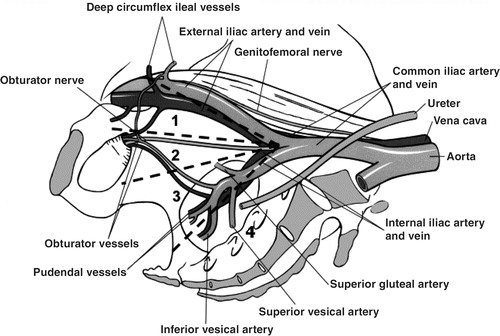

The anatomy of the prostate lymphatics was described more than 100 years ago (). These lymphatic vessels drain into the periprostatic subcapsular network from which three groups of ducts originate: the ascending duct from the cranial prostate drains into the external iliac nodes, and the lateral ducts to the internal iliac nodes and the posterior duct drain from the caudal prostate to the presacral nodes. According to lymphography studies, the four main regions for these ducts are: the internal iliac group as the primary region, the obturator nodes as the secondary, the external iliac as the tertiary, and the presacral nodes as the quartenary region. The total number of pelvic lymph nodes is approximately 40 based on extended dissection in large series of gynecological tumors.

The reported incidence of solitary metastases from prostate carcinomas at a single level were: obturator/internal iliac 60–80%, external iliac 20–25%, presacral/presciatic/perirecta 14–15%, common iliac 4% (Citation[3–7]).

Prognostic value of lymph node status

The prognostic impact of lymph node status (N-stage) is well documented. In a recent series of 1 000 consecutive patients with clinical stage T1 to T2 prostate cancers treated with radical prostatectomy and pelvic lymphadenectomy, risk factors for progression were assessed Citation[8]. Those independent in a multivariate analysis were: Gleason sum in the prostatectomy specimen, extracapsular extension, seminal vesical involvement, surgical margin status, and also lymph node metastases.

The survival of patients with positive nodes is poor and patients with this disease category have been considered incurable. A follow-up of a small cohort treated with radical prostatectomy and pelvic lymphadenectomy showed a 5-year disease free survival of only 17% Citation[9]. Longer follow-up is, however, necessary to prove that these patients are cured of the disease.

Which patients need node assessment and how can it best be performed?

Two recently published guidelines are informative, the EAU and NCCN Citation[10], Citation[11]:The European guidelines state that N-staging only has to be performed if it will influence treatment decisions. This is indicated if any of the following criteria are fulfilled: PSA >20, >T2b, Gleason score >6. Lymph node dissection is the gold standard method but CT is an option in the high-risk patient. The American guidelines recommend use of a nomogram. If this shows a >20% probability of positive nodes, CT or MRI is indicated. If imaging reveals suspicious nodes, a biopsy should be performed. Otherwise a standard lymph node dissection is recommended but an extended procedure can be considered in high-risk patients.

The performance of CT for N-staging was recently assessed in a meta-analysis based on more than 4000 patients Citation[12]. Positive nodes were detected in 2.5% with CT and in 15.3% with lymph node dissection. The sensitivity of CT was only 7%. The conclusion was that CT may be useful in T3–4 or GS >7 but an isolated high PSA should not be an indication for imaging. For the majority of patients a lymph node dissection is thus the optimal procedure for obtaining reliable N-staging.

Lymph node dissection issues

The reported frequency of positive nodes was in the 1980s 1 in 4 but in recent series only 2–3%. There are two main reasons for this. First, patient selection: nowadays the majority of operated patients belong to the T1c category due to the widespread use of PSA detection and this category is seldom operated on with lymph node dissection. Second, and more surprisingly, due to the more limited node dissection currently performed. The median number of nodes was 14 in the period 1987–89 while it was only 5 during 1999–2000 Citation[13].

What, then, is the value of an extended dissection compared with a standard one (also called modified or limited)? The terminology and definitions vary in the literature, which make comparisons difficult. The standard dissection usually entails only the external iliac and obturator nodes while the extended field also covers the internal iliac, the presacral, and the common iliac nodes ().

Figure 2. Extent of lymph node dissection performed: (1) external iliac, (2) obturator fossa, (3) internal iliac (hypogastric), (4) presacral.

Only one prospective randomized study on this issue has been published while several retrospective studies have been reported. The randomized prospective study included 123 patients who underwent extended lymph node dissection on one side and a limited procedure on the other side Citation[14]. The majority were T1c and the mean preoperative PSA was 7.4 ng/ml. The rate of positive nodes was only 6.5%. Positive nodes were found on the side of the extended dissection in four patients, on the side of the limited dissection in three, and on both sides in one. Complications were threefold higher on the side of the extended dissection (p = 0.08). The authors conclude that the extended lymph node dissection identifies few with positive nodes not found by the limited to the price of an increased risk of complications.

Two comparative retrospective studies have been published, one favoring the extended Citation[7] and one against this approach Citation[15]. In the later the authors concluded that the extended lymph node dissection offered no advantage, especially considering the much higher complication rate. summarizes the results of these retrospective studies.

Table I. Distribution of number of nodes and incidence of positive nodes according to the extent of lymph node dissection in retrospective studies.

In a large retrospective series with extended dissection a correlation between lymph node results and PSA and Gleason score was reported Citation[16]. Positive nodes occurred in 12% among those with PSA less than or equal to 10 and in 7% of those with the same PSA cutoff together with a Gleason score of less than 7. They stated that “a significant number of patients would have been understaged and left with diseased nodes when applying the current criteria for omitting lymphadenectomy”. Their recommendation was to consider a meticulous lymphadenectomy for correct staging in all patients undergoing radical prostatectomy for prostate cancer, with the exception of patients with a Gleason score <5 and a PSA <or = 10 ng/ml.

The number of lymph nodes removed can serve as a quality control of the extent of the dissection area. In retrospective studies patients with more nodes excised had less progression than those with fewer nodes. The minimal number needed to achieve this goal in these reports was 13–15 nodes Citation[17], Citation[18]. However, results reported can be confounded by different views on margins by different surgeons. A surgeon who removes more nodes is very likely also to excise the primary tumor more widely than one with another attitude.

In summary, a limited dissection will miss more than half of positive nodes. In other malignancies recommendations have been issued regarding the minimum number of nodes that should be examined. In the UICC classification for cervical and endometrial cancer 10 is recommended and for bladder cancer 15 has been proposed Citation[19]. Removing approximately 20 lymph nodes has been proposed as a guideline for a standard prostate pelvic lymph node dissection based on an autopsy series Citation[2]. Thus between 15 and 20 nodes seems a reasonable number for prostate cancer. Whether this extended approach has a curative value has been discussed for prostate as well as many other forms of cancer. In gastric cancer Citation[20], Citation[21] prospective trials have not found a survival benefit with extended dissection despite several retrospective reports to the contrary. For prostate this also has to be tested in controlled studies. Finally, the higher complication rate with extended dissection has to be considered.

New developments

High-resolution MRI with magnetic nanoparticles is a promising new technique. It is based on lymphotropic super-paramagnetic nanoparticles that after injection are internalized by macrophages in lymph nodes. This causes changes in magnetic properties detectable by MRI. In a recent study 80 patients with T1–T3 tumors had the imaging results correlated with histopathological findings from lymph node dissection Citation[22]. The experimental MRI correctly identified all patients with nodal metastases, and in a node-by-node analysis had a significantly higher sensitivity than conventional MRI (90.5% vs. 35.4%, p < 0.001) or nomograms. It allowed the detection of small (>2 mm) and otherwise undetectable lymph node metastases.

Sentinel lymph-node (SLN) investigations

The original sentinel node concept was first described in a cancer of the parotid gland Citation[23] and clinically implemented in penile carcinoma Citation[24]. It was then proposed that the lymphatic drainage from a primary tumor goes to one particular regional lymph node—called the sentinel node—and then continues to other nodes. The tumor status of the sentinel node was believed to reflect the status of the regional lymphatic field. More than 10 years ago that concept evolved and, based on dynamic investigations of lymphatic drainage in each patient, it was clearly shown that the site of the sentinel node was specific for each individual.

It is now also established that more than one sentinel node can be seen in the same individual Citation[25]. Use of lymphatic mapping and sentinel node biopsy to identify patients with lymph node metastasis is well established in those with malignant melanoma Citation[26] and intensively studied in those with breast cancer Citation[27]. In the urological field it has been used for penile and urinary bladder cancer Citation[28], Citation[29].

Recently the method has been tried for sentinel lymph node identification in patients for whom lymph node dissection and prostatectomy is planned. The radioactive tracer is transrectally injected into the prostate under ultrasound guidance followed by lymphoscintigraphy. During surgery, either open or laparoscopic, a gammaprobe was used for detection. In a large German study with open surgery, 335/350 patients had at least one SLN Citation[30]. In two patients, metastases in non-SLN were found, i.e. they were false negatives. Two smaller studies verified the possibility to delineate SLN during laparoscopic surgery Citation[31], Citation[32]. All these studies detected metastasis outside the standard lymphadenectomy area, some exclusively in this area. In summary, SLN identification is feasible in prostate cancer.

Positron emission tomography (PET)—prostate cancer

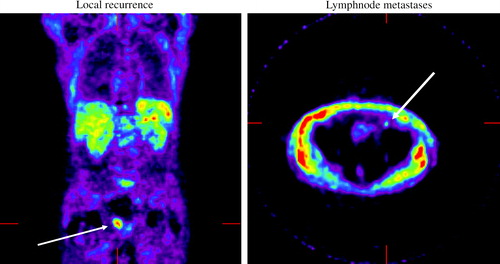

The initial results with PET in prostate cancers were disappointing. In an overview from 2003 it was concluded that “The role of FDG-PET is limited in detecting localized prostate cancer secondary to its generally low metabolic rate and interference from tracer accumulation in the ureters and urinary bladder” Citation[33]. However, new tracers have been applied and tested, mostly at the time of biochemical recurrence post-prostatectomy. In a German study, acetate was more useful than fluoro-2-deoyglucose (FDG) in the detection of local recurrences and regional lymph node metastases Citation[34]. FDG, on the other hand, appeared to be more accurate in visualizing distant metastases. A Dutch study evaluated choline as a tracer Citation[35]. The site of recurrence was detected in 78% of patients after external beam radiation therapy and in 38% after radical prostatectomy. No PET scans were positive when PSA was below 5 ng/ml. The advent of combined PET/CT imaging improves the possibilities to anatomically locate suspect lesions. In the first report this technique had a sensitivity of 91% to detect prostate cancer using choline as tracer Citation[36]. All investigations in this study were negative after hormonal ablation.

Our own experience, with PET acetate for localization of tumor relapse after radical prostatectomy, is promising (). Twenty men who had an increase in PSA on two consecutive occasions following radical prostatectomy were included. At the time of PET examination mean PSA was 2.4 ng/ml. In 15/20 of the cases pathological uptake of acetate was identified. This is now tested in patients prior to lymph node dissection. Preliminary results also show good possibilities to visualize lymph nodes with this technique.

In conclusion, recent experience from extended lymph node dissection and experimental staging techniques shows that current staging modalities often fail to detect regional lymph node metastases. With better staging initially patients with positive nodes can be saved from unnecessary local therapy as prostatectomy or brachytherapy. Instead they could be recommended systemic treatments Citation[36]. Lymph node staging is indicated in categories when therapy with curative intent is planned and current results are less encouraging. Thus, patients with Gleason score >6 or PSA >10 ng/ml could fit into this category. The dissection should cover the internal iliac region as well as the commonly dissected obturator and external iliac regions. The number of excised nodes should be 15 or more. The new developments in imaging are promising and should now be prospectively tested in clinical trials.

References

- Bubendorf L, Schopfer A, Wagner U, et al. Metastatic patterns of prostate cancer: an autopsy study of 1,589 patients. Hum Pathol 2000; 31: 578–83

- Cunéo B, Maraille M. Note sur les lymphotiques de la vessie. Bull Mem Soc Anat 1901; 6: 649–651

- Weingartner K, Ramaswamy A, Bittinger A, Gerharz EW, Voge D, Riedmiller H. Anatomical basis for pelvic lymphadenectomy in prostate cancer: results of an autopsy study and implications for the clinic. J Urol 1996; 156: 1969–71

- McLaughlin AP, Saltzstein SL, McCullough DL, Gittes RF. Prostatic carcinoma: incidence and location of unsuspected lymphatic metastases. J Urol 1976; 115: 89–94

- Golimbu M, Morales P, Al-Askari S, Brown J. Extended pelvic lymphadenectomy for prostatic cancer. J Urol 1979; 121: 617–20

- Fowler JE, Jr, Whitmore WF, Jr. The incidence and extent of pelvic lymph node metastases in apparently localized prostatic cancer. Cancer 1981; 47: 2941–5

- Heidenreich A, Varga Z, Von Knobloch R. Extended pelvic lymphadenectomy in patients undergoing radical prostatectomy: high incidence of lymph node metastasis. J Urol 2002; 167: 1681–6

- Hull GW, Rabbani F, Abbas F, Wheeler TM, Kattan MW, Scardino PT. Cancer control with radical prostatectomy alone in 1,000 consecutive patients. J Urol 2002; 167: 528–34

- Agjertson CJ, Asher P, Sclar JD, et al. Abstract to AUA 2004. J Urol 2004; 171: 385

- Aus G, Abbou CC, Pacik D, Schmid HP, van Poppel H, Wolff JM, Zattoni F, EAU Working Group on Oncological Urology. EAU guidelines on prostate cancer. Eur Urol 2001; 40: 97–101

- NCCN guidelines. Available online at:, , http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/PDF/prostate.pdf.

- Abuzallouf S, Dayes I, Lukka H. Baseline staging of newly diagnosed prostate cancer: a summary of the literature. J Urol 2004; 171: 2122–7

- Dimarco DS, Zincke H, Slezac JM, Bergstralh EJ, Blute ML, Rochester MN J. Abstract to AUA. J Urol 2003; 169

- Clark T, Parekh DJ, Cookson MS, et al. Randomized prospective evaluation of extended versus limited lymph node dissection in patients with clinically localized prostate cancer. J Urol 2003; 169: 1445–7

- Stone NN, Stock RG, Unger P. Laparoscopic pelvic lymph node dissection for prostate cancer: comparison of the extended and modified techniques. J Urol 1997; 158: 1891–4

- Burkhard FC, Bader P, Schneider E, Markwalder R, Studer UE. Reliability of preoperative values to determine the need for lymphadenectomy in patients with prostate cancer and meticulous lymph node dissection. Eur Urol 2002; 42: 84–90

- Di Blasio CJ, Fearn P, Song SH, Kattan MW, Scardino PT. Proceedings of the AUA. J Urol 2003;169(Suppl).

- Bader E, Spahn M, Huber R, et al. Abstract to EAU. 2004. Eur Urol 2004; 3: 16

- International Union Against Cancer (UICC). TNM classification of malignant tumors 5th ed. New York. Wiley; 1997.

- Hartgrink HH, van de Velde CJ, Putter H, et al. Extended lymph node dissection for gastric cancer: who may benefit? Final results of the randomized Dutch gastric cancer group trial. J Clin Oncol 2004; 22: 2069–77

- Cuschieri A, Weeden S, Fielding J, et al. Patient survival after D1 and D2 resections for gastric cancer: long-term results of the MRC randomized surgical trial. Surgical Co-operative Group. Br J Cancer 1999; 79: 1522–30

- Harisinghani MG, Barentsz J, Hahn PF, et al. Noninvasive detection of clinically occult lymph-node metastases in prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 2003; 348: 2491–9

- Gould EA, Winship T, Philbin PH, Kerr HH. Observations on a “sentinel node” in cancer of the parotid. Cancer 1960; 13: 77–8

- Cabanas RM. An approach for the treatment of penile carcinoma. Cancer 1977; 39: 456–66

- Nieweg OE, Tanis PJ, Kroon BB. The definition of a sentinel node. Ann Surg Oncol 2001; 8: 538–41

- Morton DL, Wen DR, Wong JH, et al. Technical details of intraoperative lymphatic mapping for early stage melanoma. Arch Surg 1992; 127: 392–9

- Keshtgar MRS, Ell PJ. Clinical role of sentinel-lymph-node biopsy in breast cancer. Lancet Oncol 2002; 3: 105–10

- Lont AP, Horenblas S, Tanis PJ, Gallee MP, van Tinteren H, Nieweg OE. Management of clinically node negative penile carcinoma: improved survival after the introduction of dynamic sentinel node biopsy. J Urol 2003; 170: 783–6

- Sherif A, De La Torre M, Malmstrom PU, Thorn M. Lymphatic mapping and detection of sentinel nodes in patients with bladder cancer. J Urol 2001; 166: 812–15

- Wawroschek F, Vogt H, Wengenmair H, et al. Prostate lymphoscintigraphy and radio-guided surgery for sentinel lymph node identification in prostate cancer. Technique and results of the first 350 cases. Urol Int 2003; 70: 303–10

- Jeschke S, Leeb K, Nambirajan T, et al. Abstract to EAU. E Urol 2004; 3: 16

- Corvin S, Eichorn H, Wurm TM, et al. Abstract to EAU. E Urol 2004; 3: 549

- Janzen NK, Laifer-Narin S, Han KR, et al. Emerging technologies in uroradiologic imaging. Urol Oncol 2003; 21: 317–26

- Fricke E, Machtens S, Hofmann M, et al. Positron emission tomography with 11C-acetate and 18F-FDG in prostate cancer patients. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2003; 30: 607–11

- De Jong IJ, Pruim J, Elsinga PH, Vaalburg W, Mensink HJ. 11C-choline positron emission tomography for the evaluation after treatment of localized prostate cancer. Eur Urol 2003; 44: 32–8

- Gottfried HW, Bartsch G, Messe PM, et al. 11C-Choline-PET/CT a new image modality in prostate cancer detection. Abstract to AUA. J Urol 2004; 171 (Suppl): 480

- Nilsson S, Norlen BJ, Widmark A. A systematic overview of radiation therapy effects in prostate cancer. Acta Oncol 2004; 43(4)316–81

![Figure 1. Lymphatic drainage of the prostate (Adapted from [2]).](/cms/asset/cdda42a0-9eca-49b0-857c-0e7488834f93/ionc_a_11317377_uf0001_b.jpg)