Abstract

Endocrine therapy of prostate cancer has mostly been reserved to patients with advanced stages of the disease. The principle for endocrine treatment of prostate cancer is elimination of stimulatory effects of testicular androgens on the prostate tumour cells. This can be achieved by surgical removal of the testes, by inhibition of pituitary gonadotrohin secretion by GnRH-angonsists or antagonists, by oestrogens or by non-steroidal antiandrogens. Since non-steroidal antiandrogens have fewer side-effects than castrational therapies, there is an increased interest for using endocrine treatment as adjuvant therapy after localized treatment. At least in certain stages of the disease, early hormonal treatment may have survival benefits. The timing of endocrine therapy, the usage of combined androgen blockade and intermittent endocrine therapy will be discussed in this overview.

Introduction

Androgen ablative therapy has been the mainstay for the management of advanced prostate cancer (PC) since the middle of the last century. Endocrine manipulation is still the prime therapeutic strategy for patients in whom the disease is not considered curable with local radical therapy, either surgery or radiotherapy. In general, the patients for whom endocrine therapy is indicated are those with PC with extraprostatic growth, with or without lymph node metastases, or cancer with distant metastases. In addition, patients with rising PSA levels after primary curative intended therapy could also sometimes be treated with hormonal therapy.

Endocrine treatment methods to achieve androgen ablation

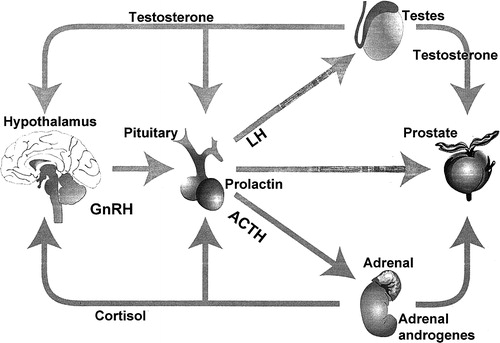

The principle of androgen ablation is elimination of testicular androgens, which can be achieved in several ways: by surgical removal of the testicles, by inhibition of the LH/FSH secretion from the pituitary by down-regulation of the GnRH-receptors with GnRH agonists or GnRH antagonists, by oestrogens reducing the secretion of GnRH by the hypothalamus, or by blocking the effect of androgens on the prostate with antiandrogens.

Approximately 70 to 80% of treated patients with metastatic disease will experience symptomatic relief, i.e. reduced bone pain, better performance status, and a general improvement with increased sense of well-being following androgen ablation Citation[1]. In many of the treated patients, an objective response can be demonstrated. Endocrine treatment of PC patients is considered as palliative, and relapse occurs if the patient survives competing causes of death. Side effects and toxicity associated with endocrine manipulation are common, although mild compared to other forms of anticancer therapies. Loss of sexual function is the most obvious, while other side effects such as fatigue, depression, vasomotor symptoms (flush) and lack of energy are poorly defined, but together they all may result in reduced quality of life Citation[2].

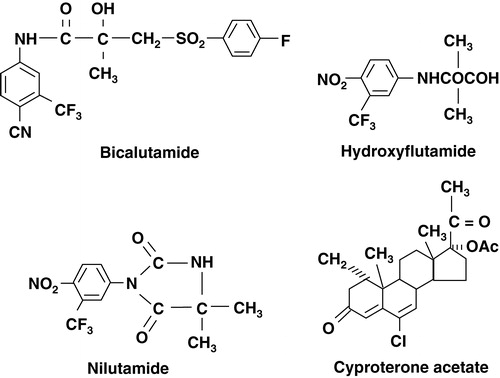

Figure 1. The endocrine control of the prostate gland. The main regulator is testosterone, which is produced from the testes (95%) and the adrenals (5%). Testosterone production is regulated by LH (testes) and ACTH (adrenals). The pituitary production of LH is regulated by GnRH from the hypothalamus.

Bilateral orchidectomy

Bilateral orchidectomy is the golden standard, is easy to perform and has a definite and rapid onset of action leading to castrate levels of serum testosterone within 24 hours. It is, however, a surgical procedure that is associated with psychological problems, particularly in younger males. Loss of libido and sexual function is following orchidectomy. Bilateral orchidectomy also causes loss of muscle mass, physical and psychological energy, even cognitive decline, bothersome hot flushes, osteoporosis (in 50% of patients after three years) with an increased risk of fractures, and a 10–15% drop in haemoglobin levels, which may cause anaemia in some patients Citation[3].

There are some global absolute indications for bilateral orchidectomy including patients with manifest or imminent spinal compression, those with severe pain when immediate reduction of testosterone into castrate range is necessary and poor compliance with tablet intake or injections at regular intervals.

GnRH Agonists

GnRH agonists are small polypeptides given parenterally, mostly as 3-monthly depot injections. Treatments with GnRH agonists are associated with an initial flare of symptoms, due to the initial stimulation of the pituitary to produce more LH and thus stimulate the testicles to produce more testosterone. Antiandrogens should be given at the beginning of treatment with GnRH agonists (for the first 4 weeks) to prevent this initial flare of symptoms at least in patients with metastases. The efficacy and adverse effects of GnRH agonists are comparable to surgical castration.

Oestrogens

Oral oestrogens were used in the early days, but came under criticism because of cardiovascular and thromboembolic side-effects. However, by giving oestrogens parenterally it is possible to by-pass the portal circulation and to avoid the effects on the liver production of various coagulation factors. The Scandinavian Prostatic Cancer Group (SPCG) investigated the concept of parenteral oestrogens in a large randomized trial comparing patients with previously untreated metastatic cancer receiving either parenteral oestrogen or combined androgen blockade Citation[4]. This study showed that parenteral oestrogens and total androgen blockade were equally effective in the treatment of advanced prostatic cancer and there was no increase in cardiovascular mortality associated with parenteral oestrogens.

GnRH antagonists

GnRH antagonists have an advantage compared to agonists, as an immediate inhibition of LH secretion is achieved thus avoiding the onset of a flare reaction. It means that the antagonists cause an immediate drop in LH levels and the patients reach castrate levels of testosterone within a few days Citation[5].

Antiandrogens

Two types of antiandrogens exist; steroidal types, such as cyproterone acetate, and non-steroidal types, such as flutamide, bicalutamide and nilutamide. Steroidal antiandrogens have, in addition to its antiandrogenic effects, also some progestational activity, which through negative feedback action on the pituitary, leads to a slight reduction of testosterone secretion Citation[6]. Non-steroidal antiandrogens are purely antiandrogenic and may block the receptors on the pituitary, sometimes giving rise to increased LH and testosterone production Citation[7].

Non-steroidal antiandrogens are mainly used as flare protection for four weeks when treatments with GnRH agonists are initiated. Non-steroidal antiandrogen monotherapy is rather well tolerated, although gynaecomastia is a problem associated with bicalutamide. Antiandrogen mono-therapy is considered to be a treatment option in well informed patients who wish to remain sexually active Citation[8].

Usage of endocrine therapy in prostate cancer

Timing of endocrine therapy

Endocrine therapy has been used to treat prostate cancer for more than half a century. Initially, options were limited to bilateral orchiectomy, which is unacceptable to many men for psychological reasons Citation[9], Citation[10], or oestrogen therapy. Randomised placebo-controlled studies of oestrogen therapy (diethylstilbestrol) in men with newly diagnosed advanced prostate cancer Citation[11] was conducted in the early 1970s by the Veterans Administration Cooperative Urological Group (VACURG). It was clearly shown that immediate hormonal therapy delayed disease progression, but the excessive risk of cardiovascular toxicity associated with diethylstilbestrol confounded any survival advantage. With this background, it became routine practice to defer hormonal therapy until symptomatic progression. The availability of GnRH agonists and non-steroidal antiandrogens from the 1980s and onwards, made the concept of immediate hormonal intervention more attractive to patients and clinicians. Despite the fact that endocrine therapy is palliative and not biologically curative, increased uptake of such treatment could be contributing to declines in mortality by delaying death from prostate cancer long enough for the patient to die of unrelated causes Citation[12].

The timing of hormonal therapy may affect survival rates. Experiments in animals have shown that initiation of hormonal manipulation early in the course of tumour growth can substantially improve survival. One study demonstrated a significant negative linear correlation between the mean survival time after tumour inoculation and the time of castration in the commonly used Dunning R-3327 rat prostate cancer model Citation[13]. Mean survival was 470 days in rats castrated at the time of tumour inoculation, compared with approximately 350 days in untreated control rats and those in which castration was delayed for 250 days after tumour inoculation. Studies using a transgenic mouse model of prostate cancer have also shown that early castration significantly reduces prostate tumour growth and improves cancer-free survival Citation[14], Citation[15].

These observations in experimental prostate cancer models are supported by evidence from randomised, controlled clinical trials. Some studies investigating adjuvant hormonal therapy, using a GnRH agonist or bilateral orchiectomy, after radiotherapy has reported survival results Citation[16–19]. In one of those studies, 415 men with T1-4 disease and no evidence of lymph node involvement were randomised to treatment with radiotherapy alone or radiotherapy plus GnRH agonist for 3 years Citation[17], Citation[20]. At a median follow-up of 66 months, overall survival was significantly improved with adjuvant GnRH compared with radiotherapy alone Citation[17]. Similar results were obtained in another study comparing radiotherapy alone with radiotherapy in combination with bilateral orchiectomy in men with locally advanced prostate cancer Citation[21]. Adjuvant therapy was associated with an increase in median survival of more than 3 years, with significantly higher mortality in the control group compared with the adjuvant group. In a third study, 977 men with locally advanced prostate cancer were randomised to receive radiotherapy alone or radiotherapy plus GnRH indefinitely or until disease progression Citation[16], Citation[19]. Although there were no significant differences between the two groups for either 5- or 8-year overall survival rates, a subgroup analysis of patients with high-grade Gleason scores Citation[8–10] who had not previously undergone radical prostatectomy revealed a significant improvement in overall survival in favour of adjuvant therapy. In patients planned for radical prostatectomy and found to have nodal metastases, immediate hormonal therapy was compared with the same therapy deferred until clinical progression Citation[21]. At a median follow-up of 7.1 years, overall survival was significantly improved in the immediate therapy group compared with the deferred therapy.

In a large study performed by the Medical Research Council, benefits of immediate hormonal therapy in men with previously untreated locally advanced or asymptomatic metastatic disease was shown Citation[22], Citation[23]. A total of 938 patients were randomised to medical or surgical castration initiated either at diagnosis or delayed until symptoms developed. In the first analysis, conducted after 74% of the patients had died, overall mortality was significantly reduced with immediate endocrine therapy Citation[22]. However, when patients were stratified according to metastatic status at study entry, the difference in mortality between the two treatment groups remained significant only in patients without distant metastasis. A second analysis after 86% of patients had died continued to demonstrate a significant difference in overall survival favouring immediate therapy, but this difference was no longer statistically significant for patients without metastasis Citation[23]. In addition, results have been reported from an EORTC study comparing early versus delayed hormonal therapy in men with nodal metastasis but without skeletal metastasis. A 23% survival difference in favour of early treatment was observed after a median follow-up of 8.7 years, but this was not statistically significant Citation[24].

The value of the non-steroidal antiandrogen bicalutamide 150 mg compared with placebo, given in addition to standard care, in 8 113 patients with localised or locally advanced prostate cancer, has been investigated in the Early Prostate Cancer (EPC) programme Citation[25], Citation[26]. Recently, survival data was published showing that early bicalutamide provides significantly improved survival in patients with locally advanced disease Citation[27], Citation[28]. On the other hand, in patients with localized disease a decreased survival was observed after early bicalutamide treatment. It was concluded that in previously untreated patients there may be a tumour burden below which endocrine therapy provides no benefit or may even decrease survival.

Combined androgen blockade

Early reports from nonrandomised studies supported the concept of complete androgen blockade meaning that castrational treatment (surgical or medical), which is used to prevent testicular production of testosterone, is combined with an antiandrogen to block the action of adrenal androgens Citation[29]. The results from these early reports led to several controlled trials to test the hypothesis that men with advanced prostate cancer had a longer survival after combined androgen blockade than after monotherapy. The results from these trials were partly contradictory. In a recent metaanalysis Citation[30] and a systematic review Citation[31], a small survival advantage was described after combined treatment at 5 years follow-up. However, it was concluded that this small (2.9%) benefit in survival must be balanced to the increased risk for adverse effects and the higher costs with combined androgen blockade.

Intermittent endocrine therapy

Intermittent androgen ablation means a treatment strategy where periods of androgen ablative therapy (medical) is stopped when PSA level has reach its nadir (often defined as below 4 ng/ml), followed by a period when the patients are without any endocrine therapy. When PSA starts to increase again, therapy is reintroduced. Intermittent androgen suppression is based on the hypothesis that malignant prostate cancer cells would remain in a hormone dependent stage longer than under continous therapy, thus leading to prolonged survival Citation[32]. The results of experimental studies on prostate cancer models support this hypothesis Citation[33]. The concept of intermittent treatment has been tested in several open clinical studies and appears feasible Citation[34]; however, there are not yet any available data from prospective randomized trials. Randomised studies are ongoing and until the results from these studies are available, intermittent androgen blockade should still be considered experimental.

Conclusions

Androgen ablative therapies remain an important treatment strategy in advanced prostate cancer. The introduction of non-steroidal antiandrogens, with fewer side-effects than castrational therapies, has increased the interest for using endocrine treatment in an adjuvant setting after localized treatment. Available evidence suggests that the use of early hormonal treatment may extend survival, at least in certain stages of the disease. Further research is required to define the relationship between hormonal therapy and survival.

References

- Huggins C, Hodges CV. Studies on prostate cancer. 1. The effect of castration, of estrogen and of androgen injection on serum phosphatase in metastatic carcinoma of the prostate. Cancer Res 1941; 1: 293–297

- Varenhorst E. Prostate cancer treatment: Tolerance of different endocrine regimens. New Development in Biosciences 4, Endocrine management of prostatic cancer, H Klosterhalfen. Walter Gruyter, Berlin, New York 1988; 105–113

- Higano CS. Side effects of androgen deprivation therapy: monitoring and minimizing toxicity. Urology 2003; 61: 32–8

- Hedlund, PO, Henriksson, P, and the, Scandinavian Prostate Cancer Group (SPCG) –5 Trial Study. Parenteral oestrogen versus total androgen ablation in the treatment of advanced prostate carcinoma. Effects on overall survival and cardiovascular mortality. Urology 2000;55:328–333.

- Mongiat-Artus P, Teillac P. Abarelix: the first gonadotrophin-releasing hormone antagonist for the treatment of prostate cancer. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2004; 5: 2171–9

- Schröder FH. Cyproterone acetate: mechanism of action and clinical effectivness in prostate cancer treatment. Cancer 1993; 72: 3810–15

- Tyrell CJ. Casodex: a pure non-steroidal antiandrogen used as monotherapy in advanced prostate cancer. Prostate 1992; Suppl 5: 97–105

- Reese DM. Choice of hormonal therapy for prostate cancer. Lancet 2000; 355: 1474–5

- Cassileth BR, Soloway MS, Vogelzang NJ. Quality of life and psychosocial status in stage D prostate cancer. Zoladex Prostate Cancer Study Group. Qual Life Res 1992; 1: 323–9

- Cassileth BR, Soloway MS, Vogelzang NJ, et al. Patients’ choice of treatment in stage D prostate cancer. Urology 1989; 33: 57–62

- Byar DP. The Veterans Administration Cooperative Urological research Group's studies of cancer of the prostate. Cancer 1973; 32: 1126–30

- Talbäck M, Stenbeck M, Rosen M, Barlow L, Glimelius B. Cancer survival in Sweden 1960–1998 – Development across four decades. Acta Oncol 2003; 42: 637–59

- Isaacs JT. The timing of androgen ablation therapy and/or chemotherapy in the treatment of prostatic cancer. Prostate 1984; 5: 1–17

- Eng MH, Charles LG, Ross BD, et al. Early castration reduces prostatic carcinogenesis in transgenic mice. Urology 1999; 54: 1112–9

- Gingrich JR, Barrios RJ, Kattan MW, Nahm HS, Finegold MJ, Greenberg NM. Androgen-independent prostate cancer progression in the TRAMP model. Cancer Res 1997; 57: 4687–91

- Lawton CA, Winter K, Murray K, et al. Updated results of the phase III Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) trial 85-31 evaluating the potential benefit of androgen suppression following standard radiation therapy for unfavorable prognosis carcinoma of the prostate. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2001; 49: 937–46

- Bolla M, Collette L, Blank L, et al. Long-term results with immediate androgen suppression and external irradiation in patients with locally advanced prostate cancer (an EORTC study): a phase III randomised trial. Lancet 2002; 360: 103–8

- Granfors T, Modig H, Damber J-E, Tomic R. Combined orchiectomy and external radiotherapy versus radiotherapy alone for nonmetastatic prostate cancer with or without pelvic lymph node involvement: a prospective randomized study. J Urol 1998; 159: 2030–4

- Pilepich MV, Caplan R, Byhardt RW, et al. Phase III trial of androgen suppression using goserelin in unfavourable-prognosis carcinoma of the prostate treated with definitive radiotherapy: report of Radiation Therapy Oncology Group protocol 85-31. J Clin Oncol 1997; 5: 1013–21

- Bolla M, Gonzalez D, Warde P, et al. Improved survival in patients with locally advanced prostate cancer treated with radiotherapy and goserelin. N Eng J Med 1997; 337: 295–300

- Messing EM, Manola J, Sarosdy M, Wilding G, Crawford ED, Trump D. Immediate hormonal therapy compared with observation after radical prostatectomy and pelvic lymphadenectomy in men with node-positive prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 1999; 341: 1781–8

- The Medical Research Council Prostate Cancer Working Party Investigators Group. Immediate versus deferred treatment for advanced prostatic cancer: initial results of the Medical Research Council Trial. Br J Urol 1997;79:235–46.

- Kirk, D. Immediate vs. deferred hormone treatment for prostate cancer: how safe is androgen deprivation?. Br J Urol 2000;86((suppl 3)):220, (Abstr MP6.1.07)

- Kurth, KH. Early versus delayed endocrine treatment in node positive disease. Proc PACIOU VII/DUA VII: an update on sexual function in the elderly male, BPH, renal cancer and prostate cancer and basic science on prostate cancer. 2002;117–8.

- See WA, McLeod D, Iversen P, Wirth M. The bicalutamide Early Prostate Cancer Program: Demography. Urol Oncol 2001; 6: 43–7

- See WA, Wirth MP, McLeod DG, et al. Bicalutamide (‘Casodex’) 150 mg as immediate therapy either alone or as adjuvant to standard care in patients with localized or locally advanced prostate cancer: first analysis of the Early Prostate Cancer program. J Urol 2002; 168: 429–35

- Wirth MP, See WA, McLeod D, Iversen P, Morris T, Caroll K. On behalf of the Casodex early prostate cancer trialists’ group. Bicalutamide 150 mg in addition to standard care in patients with localized or locally advanced prostate cancer: Result from the second analysis of the early prostate cancer program at median followup of 5.4 years. J Urol 2004; 172: 1865–70

- Iversen P, Johansson J-E, Lodding P, Lukkarinen O, Lundmo P, Klarskov P, et al. On behalf of the Scandinavian Prostatic Cancer Group. J Urol 2004; 172: 1871–76

- Labrie F, Dupont A, Belanger A, et al. Combination therapy with flutamide and castration (LHRH agonist or orchidectomy) in advanced prostate cancer: a marked improvement in response and survival. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 1985; 23: 833–41

- Samson DJ, Seidenfeld J, Schmitt B, Hasselblad V, Albertsen PC, Bennett CL, et al. Systemic Review and meta-analysis of monotherapy compared with combined androgen blockade for patients with advanced prostate carcinoma. Cancer 2002; 95: 361–76

- Schmitt, B, Bennett, C, Seidenfeldt, J, Samson, D, Wilt, T. Maximal androgen blockade for advanced prostate cancer (Cochrane Review). The Cochrane Library 2004, Issue 4.

- Bruchovsky N, Rennie PS, Coldman AJ, Goldenberg SL, To M, Lawson D. Effects of androgen withdrawal on the stem cell composition of the Shionogi carcinoma. Cancer Res 1990; 50: 2275–82

- Trachtenberg J. Experimental treatment of prostatic cancer by intermittent hormonal therapy. J Urol 1987; 137: 785–8

- Albrecht W, Collette L, Fava C, Kariakine OB, Whelan P, Studer UE, et al. Intermittent maximal androgen blockade in patients with metastatic prostate cancer: An EORTC feasibility study. Eur Urol 2003; 44: 505–11