Abstract

Background. Chemotherapy with gemcitabine and cisplatin (GC) is an active regimen in advanced transitional cell carcinoma (TCC). Traditionally, GC has been administered as a 4-week schedule. However, an alternative 3-week schedule may be more feasible. Long-term survival data for the alternative 3-week schedule and comparisons of the feasibility and toxicity between the two schedules have not previously been published. Material and methods. We performed a retrospective analysis of patients with stage IV TCC, treated with GC by a standard 4-week or by an alternative 3-week schedule. Results. A total of 212 patients received GC (3-week; n=151, 4-week; n=61). We found no statistical differences in overall survival between the two schedules (hazard ratio 1.15, 95% CI 0.83–1.59), p=0.40). Five-year survival rates were 14.9% and 11.8% for the 3- and 4-week schedule, respectively (p=0.94). Response rates were 59.7% and 55.6%, respectively (p=0.61). Toxicity was less pronounced in the 3-week schedule with regards to neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, and transfusion rates. Hematologic toxicity at day 15 in the 4-week schedule was common, leading to dose omissions in 47% of cycles. Dose intensity for gemcitabine was accordingly lower in the 4 week-schedule. The higher dose intensity of cisplatin in the 3-week schedule, did not lead to increased renal toxicity. In 13 patients with impaired renal function, cisplatin was split into 2 days, which was feasible and efficient. Conclusion. Efficacy parameters for the GC 3-week schedule were comparable to those for the 4-week schedule, whereas toxicity was less pronounced. The 3-week schedule may be an effective and feasible alternative GC-schedule.

Cisplatin-containing combination chemotherapy is the standard treatment for patients with locally advanced and/or metastatic transitional cell carcinoma (TCC) of the urothelium. Presently, the two most widely used therapeutic regimens are GC (gemcitabine and cisplatin) and MVAC (methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin and cisplatin) with similar efficacy, but with a significantly better toxicity profile for the GC combination Citation[1], Citation[2]. In the randomized phase III study of GC vs. MVAC Citation[1] as well as in three phase II studies Citation[3–5], a 4-week schedule was applied with gemcitabine 1000 mg/m2 on day 1, 8 and 15 and cisplatin 70–75 mg/m2 on day 2.

However, a high incidence of hematologic toxicity compromises the gemcitabine dose intensity. Gemcitabine doses were modified in 37% of cycles in the phase III study Citation[1], and in 30–100% of cycles in the phase II studies Citation[3–5]. Omission of day 15 gemcitabine is reported to be by far the most common dose modification Citation[1]. According to standard protocols, omissions on day 15 in the 4-week schedule should lead to advancement of the next treatment cycle. If so, the treatment is practically administered as a 3-week regimen. The combination of gemcitabine and cisplatin is also an active regimen in advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). In NSCLC, the combination has been given in both a 3-week and a 4-week schedule. The 3-week schedule has been preferred since it enables better treatment compliance while providing a dose intensity and response rate similar to that of the 4-week schedule Citation[6], Citation[7]. In carcinoma of the cervix uteri Citation[8], in nasopharyngeal carcinoma Citation[9] as well as in pancreatic carcinoma Citation[10], a 3-week regimen has been used and found feasible.

In urothelial carcinoma, the alternative 3-week schedule has been tested in a phase II study Citation[11]. It was reported that the safety profile was good and that only 8% of doses had to be modified as opposed to 30–100% reported in the phase II studies using a 4-week schedule Citation[3–5].

In the present study, we have retrospectively evaluated all patients in our institutions, who received GC for locally advanced and/or metastatic urothelial cancer. The aim was to compare overall and progression-free survival rates, response rates, toxicity profile, dose modifications, and dose intensity for the 3- and 4-week schedule, respectively.

Impairment of the renal function is a common obstacle in this patient category, which may hamper the possibility to initiate cisplatin-containing chemotherapy. In most protocols, a glomerular filtration rate (GFR) ≥60 ml/min or a se-creatinin ≤1.25×upper normal limit is requested. However, patients with a slightly impaired renal function may apparently tolerate cisplatin if the dose is given within 2 days instead of during one day. Several studies describe regimens with 50% doses administered on day 1 and 8 Citation[12–14] but this decreases the peak-intensity of cisplatin, which may be important for the efficacy. Administration of cisplatin by use of a 50% dose on two subsequent days is another possibility. Data for the outcome of such a strategy have to our knowledge not previously been published. As part of the present study, we have evaluated the feasibility of this procedure.

Material and methods

Patients

All patients with histological proven locally advanced (T4b/N2-3) or metastatic (M1) TCC of the urothelium, treated with gemcitabine and cisplatin (GC) in a 3- or 4-week schedule at the departments of oncology at Aarhus University Hospital and Herlev University Hospital were included in the study. Patients were required to have an ECOG performance status (PS) ≤2, an adequate bone marrow reserve (white blood cell (WBC) count ≥3.5×109/l, platelets ≥100×109/l, and hemoglobin ≥10 g/dl), and patients should have no signs of CNS metastases. An adequate renal function (51Cr-EDTA plasma clearance (GFR) ≥60 ml/min) was a prerequisite for full dose cisplatin. However, patients with a GFR of 50–60 ml/min were offered cisplatin 70 mg/m2, but this dose was divided, and administered as 35 mg/m2 on day 1 and 2 in both 3-week and 4-week schedules. This was in accordance with the guidelines in the mentioned GC versus MVAC phase III protocol.

Patients recruited for ongoing protocols fulfilled all protocol criteria and all gave informed consent. The scientific ethics committee of Aarhus County approved all protocols.

Baseline evaluation consisted in a complete history and physical examination, determination of performance status, complete blood cell count and analysis of p-alkaline phosphatase. Chest x-ray and CT-scans of the abdominal cavity were baseline evaluation methods, supplementary radiological evaluation were performed according to location of metastases.

Treatment Schedules

The 4-week schedule: gemcitabine 1 000 mg/m2 repeated on day 1, 8 and 15, plus cisplatin 70 mg/m2 on day 2. Cycles were repeated every 28 days.

The 3-week schedule: gemcitabine 1 000 mg/m2 on day 1 and 8 plus cisplatin 70 mg/m2 on day 2. Cycles were repeated every 21 days.

Gemcitabine and cisplatin were both administered intravenously over 30–60 minutes. Cisplatin was administered with adequate pre- and post-hydration. Supportive care, including anti-emetics, analgesics, blood transfusions and antibiotics, were administered if appropriate and similarly in the two regimens. Granulocyte colony stimulating factors were not used routinely.

In both schedules, cycles were not initiated unless WBC was ≥3.0×109/L and platelets were ≥100×109/L. Gemcitabine doses on day 8 or 15 were omitted for WBC <2.0×109/L and for platelets <50×109/L. Omitted doses were not given subsequently. If day 15 gemcitabine was omitted, the next cycle was started on day 21, i.e. as a 3-week schedule. Doses were adjusted for non-hematologic toxicity similarly in both schedules.

Patients received a maximum of six treatment cycles unless they experienced disease progression, developed unacceptable toxicity, or the patient requested discontinuation.

Blood counts were performed weekly, performance status (PS) and weight was assessed before each cycle. Renal function was evaluated by se-creatinin before each cycle and by Cr-EDTA clearance every two cycles.

Evaluation of patients

Toxicity was graded according to the National Cancer Institute common toxicity criteria scale (CTCAE v3.0). For toxicity analysis, the worst grade for each patient in each treatment cycle was recorded. Response was classified according to World Health Organization (WHO) criteria Citation[15]. Evaluation of response was performed radiologically with the same methods as for the baseline examination and by physical examination. Response evaluations were reassessed every two cycles.

Progression-free and overall survival was measured from the day of start of chemotherapy until progression or death, respectively. Patients who were alive with no progression were censored at the date when they were last known to be progression-free. Survival data were updated February 1, 2006.

Statistical methods

The distribution of the frequency of baseline parameters was analyzed by the χ2-test. Clinical response was dichotomized as response (WHO complete response and partial response) versus no response (no change or progressive disease). Patients not evaluable for response were excluded from the response analyses. Response and toxicity ratios were evaluated by the χ2-test. Weighted ratios and χ2-values were constructed by the Mantel-Haenszel method. For transfusion rates the Mann-Whitney U-test was used.

Dose intensity was calculated according to the methods of Hryniuk Citation[16].

Survival curves were estimated using the Kapplan Meier method. The relationships between survival and pretreatment factors as well as treatment were analyzed with the log-rank test. Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses were performed to evaluate the prognostic impact of pretreatment factors in relation to survival, and the statistical significance of the hazard ratios was estimated by Walds test. Data for the 4-week schedule represented the baseline parameters. Factors with a p-value ≤0.10 in the univariate analyses were included in the multivariate analysis. The final model was determined by backward selection. All p-values are two-sided.

All data calculations were performed using the SPSS Statistical Software (v. 13.0, Chicago, IL).

Results

A total of 212 patients with locally advanced and/or metastatic bladder cancer were treated with GC in a 3- or 4-week schedule in the period from January 1, 1997 to June 1, 2004. Among this group of patients, 151 patients were treated with the 3-week schedule and 61 patients with the 4-week schedule. The clinical features of the patients are presented in . Baseline parameters were not evenly distributed for all prognostic parameters. We found an uneven distribution of patients with and without visceral metastases, of patients with stages M0 vs. M1 and of patients with and without elevated P-alkaline phosphatase, with more patients with poor prognostic parameters in the 4-week schedule.

Table I. Baseline clinical patient characteristics.

For patients at risk at the time of analyses, the median follow-up-time was 48.5 months (range 21–88 months). No patients were lost to follow-up.

Overall survival

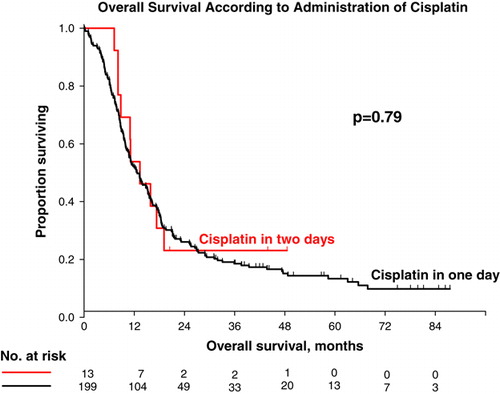

Survival data are summarized in . At the time of analysis, 178 patients had died; 126(83.4%) vs. 52(85.2%) in the 3 week vs. the 4-week schedule, giving a censoring rate of 16% (16.5% vs.14.7%). Median overall survival for all patients independent of schedule was 12.7 months (range 0.2–87.5). To assess the assumption of proportional hazards, we performed a regression analysis with time-dependent covariates and found no significant effect of the interaction term of time and schedule. There were no statistically significant differences in overall survival for patients in the two different GC-schedules. Median overall survival was 12.5 months (95% CI 10.3–14.7) vs. 14.7 months (95% CI 10.8–18.7) for the 3-week and 4-week schedule, respectively. The hazard ratio (HR) was 0.87 (95% CI 0.63–1.20; Walds p = 0.40). The survival curves are presented in a. Adjusting for baseline prognostic parameters revealed no statistical significant differences in the survival for the 3-week vs. the 4-week schedule ().

Figure 1. Survival for all patients. a) Overall survival, 3-week vs. 4-week schedule; b) Progression-free survival, 3-week vs. 4-week schedule.

Table II. Survival parameters.

Table III. Summary of efficacy outcomes.

Progression-free survival

Data are summarized in . At the time of analysis, 187 patients had progressed or died (3-week, n = 131, 86.8%; 4-week, n = 56, 91.8%). This means 25 patients were alive without progression giving a censoring rate of 11.8% (13.2% vs. 8.2%). There were no statistically significant differences in the median progression-free survival rates for patients in the two different GC-schedules. Median time to progression was 9.8 months and 8.6 months with the 3-week and 4-week schedule, respectively, HR 0.79 (0.58–1.08; Walds p = 0.14). b provides the progression-free survival curves for the two schedules. Adjusting the HR for prognostic parameters revealed no statistical significant differences in survival for the 3-week vs. the 4-week schedule ().

Analysis of effect of prognostic parameters

Multivariate Cox proportional hazards analyses were performed to evaluate the impact of pretreatment prognostic factors in relation to overall and progression-free survival. Presence or absence of visceral metastases, PS, level of hemoglobin, and level of alkaline phosphatase all revealed a p-value <0.1 in the Cox univariate analyses and were included in the multivariate analysis. The final model included PS (HR = 2.02; 95% CI 1.26–3.24), presence and absence of visceral metastases (HR = 1.81; 95% CI 1.33–2.47) and level of hemoglobin (HR = 1.57; 95%CI 1.16–2.13). Due to the uneven distribution of pretreatment prognostic parameters, and in order to evaluate the effect of the two different schedules on survival parameters adjusted for the independent prognostic variables, we included schedule in the final model. We found no statistically significant effect of the treatment schedule for overall survival (p = 0.39), nor for progression-free survival (p = 0.98), see .

Response analyses

Response evaluation was performed according to WHO criteria. All analyses were done by a skilled radiologist and if there were any doubt at the time of assessment, a reevaluation was performed. A total of 183 patients were evaluable for response (3-week, n = 129, 85.4%; 4-week, n = 54, 88.5%). The overall response rate was 59.7% vs. 55.6% in the 3-week vs. the 4-week schedule, respectively (p = 0.61, χ2-test). The complete response rate was 21.7% vs. 21.8% (p = 0.99). Mantel Haenszel weighted Risk Ratios (RR) and χ2-tests were computed with correction for absence and presence of visceral metastases. This analysis did not change the results ().

Toxicity and dose intensity

National Cancer Institute CTC grades 3 and 4 toxicities are provided in . Significant less grade 3 and 4 thrombocytopenia and neutropenia was observed in the 3-week schedule compared with the 4-week schedule. For neutropenic fever, the RR was 0.40 but with only few events in both schedules. The RBC transfusion rate was significantly lower in the 3-week schedule. Renal toxicity leading to dose reductions was not more common in the 3-week than in the 4-week schedule. Mantel Haenszel weighted RR and χ2-tests were computed with correction for absence and presence of visceral metastases, without changing the results of the analyses.

Table IV. Toxicity ratios, n = 212.

Patients on the 3-week schedule received a total of 799 cycles (88.2% of planned), compared with 314 cycles (85% of planned) on the 4-week-schedule. The median number of cycles was six in both schedules. Dose intensity was 96.0% and 92.0% for gemcitabine and for cisplatin, respectively, in the 3-week schedule as opposed to 80.7% and 93.0%, respectively, in the 4-week schedule ().

Table V. Dose intensity and compliance.

Dose adjustments were necessary in 19% of cycles in the 3-week schedule compared to 62% in the 4-week schedule. The by far most common dose adjustment occurred on day 15 in the 4-week regimen, where doses were omitted in 47% of all treatment cycles (). According to protocol criteria, omissions on day 15 should lead to modification of the schedule by starting the next cycle on day 21. In 35 of 149 cases of day 15 omissions, the cycle was the last in the treatment course and there was no subsequent treatment to be advanced. In 59 of the remaining 114 cases (51%), the next cycle was accelerated as planned. In 55 cases (48%), acceleration of the next cycle was not possible due to logistic reasons (32%), ongoing hematologic toxicity (12%), or due to the general condition of the patients (4%).

Patients with GFR 50-60 ml/min

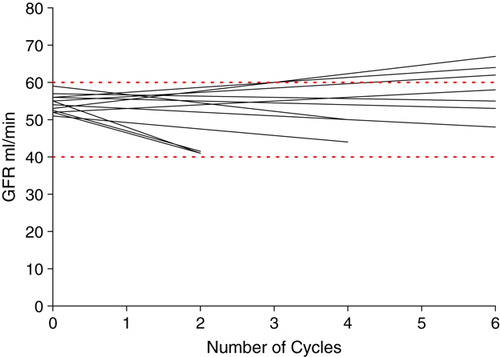

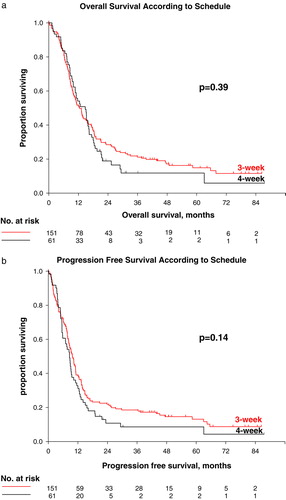

A slightly impaired renal function with a GFR of 50–60 ml/min at admission was found in 13 patients. These patients were offered cisplatin as a split dose with 35 mg/m2 on day 1 and 35 mg/m2 on day 2. Remarkably, ten out of these 13 patients had metastatic disease, hereof eight patients with visceral metastases. The survival rate for these few patients was similar to that for patients treated with cisplatin 70 mg/m2 in one day. Median survival was 13.3 months (95% CI 7.6–19.0) in the split-dose schedule compared to 12.7 months (95% CI 10.3–15.1) in patients receiving cisplatin on one day (p = 0.76). Survival curves are illustrated in . The response rate was also similar to that of the group of patients receiving cisplatin in one day. Two patients had a CR and four had a PR yielding an overall response rate of 46%. The effect on renal function as indicated by changes in GFR is illustrated in . Five patients had decrements of GFR below 50 ml/min and stopped cisplatin treatment before completion of the six cycles.

Discussion

Locally advanced and metastatic TCC is a disease with a poor prognosis. Cisplatin-containing combination chemotherapy is the treatment of choice and GC has proven to be efficient, well tolerated, and with long term survival rates comparable to other combinations Citation[2]. In the randomized phase III study of GC versus MVAC, a 28 day schedule was chosen to limit differences and biases since it allowed administration of cisplatin in the same schedule and dose as in the MVAC arm Citation[1]. On the basis of this randomized study, GC became an alternative to MVAC as a standard regimen and, consequently, as a 4-week GC schedule. Since then, this GC 4-week schedule has been applied in clinical trials concerning advanced urothelial cancer. However, in many centers, especially outside the framework of a clinical trial, a 3-week GC schedule is often applied in patients with locally advanced and/or metastatic bladder cancer. Optimally, a non-standard schedule should be compared with the standard 4-week schedule in a randomized trial. Such a randomized study would require a very large number of patients and will-from a realistic point of view-probably not be initiated. Therefore, we present this non-randomized comparison of the 3-week versus the 4-week GC schedule in a group of consecutive and unselected patients with locally advanced and/or metastatic urothelial cancer.

The effect and feasibility of a 3-week combination of GC has also been investigated in several other cancer types especially lung cancer, where the 3-week schedule is reported to be well tolerated and efficient Citation[6], Citation[17], Citation[18]. Patients with lung cancer may be comparable to patients with bladder cancer regarding age and smoking related comorbidity, and the obtained feasibility data in lung cancer may thus be of importance for patients with bladder cancer.

Data on efficacy, toxicity and compliance from phase II and phase III studies on GC in bladder cancer are presented in and together with data from a randomized phase II study of GC administered in a 3-week schedule vs. a 4-week schedule in non-small-cell lung cancer published by Parra et al. Citation[6]. The studies may have different criteria of dose adjustments and patient selection, which may reflect dose intensity and toxicity data. When comparing our results with those in other studies, these limitations should be taken into consideration.

Table VI. Treatment compliance.

Table VII. Presentation of 3- and 4-week GC Schedules.

We found no significant differences in survival or response for the two treatment schedules. Survival and response rates were comparable to previously published data on bladder cancer Citation[1], Citation[3–6], Citation[11], Citation[14], Citation[19] (). The results of the univariate and multivariate analyses of clinical prognostic parameters were also in accordance with previous findings Citation[1], Citation[20], Citation[21]. We found that hematological toxicity was significantly lower in the 3-week schedule compared to the 4-week schedule. Toxicity data is in line with the findings by Parra et al. Citation[6]. This randomized phase II study was conducted in patients with lung cancer comparing GC administered as a 3-week vs. a 4-week schedule. Although toxicity was the main endpoint and the study had a limited number of patients, no statistical differences in survival between the two schedules were reported and compliance was improved in the 3-week schedule Citation[6]. Both findings are in accordance with the results of the present study.

We report that dose adjustments were necessary in 19% in the 3-week schedule compared to 62% of cycles in the 4-week schedule. As reported by von der Maase et al. Citation[1], and Parra et al. Citation[6], the by far most common reason for dose adjustment was hematological toxicity on day 15, resulting in omission or reduction of gemcitabine. In our study, gemcitabine was omitted on day 15 in 47% of cycles. It is generally advised that the next treatment cycle is started on day 21 in case of day 15 omissions. However, this was only possible in 51% of cases, and led to a significant decrease in dose intensity for gemcitabine in the 4-week schedule (). Advancement of treatment may lead to logistic problems and frustrations for the patient as well as for the health care system. This may be illustrated by the fact that in 32% of the treatment cycles the subsequent cycle was not advanced due to logistic reasons.

When comparing the 4-week schedule in the present study with the previously presented studies of the 4-week schedule (), we found higher toxicity rates regarding thrombocytopenia and number of dose adjustments. This may be due to the unselected character of our patient material and the high frequency of patients with poor prognostic parameters.

In the 3-week schedules (), compliance was very similar to the results reported by Adamo et al. Citation[11] and Parra et al. Citation[6]. In the study in an adjuvant setting by Flechon et al. Citation[19], a higher dose of gemcitabine was used, which may also account for the higher frequency of neutropenia.

Nephrotoxicity, indicated by a decrease in GFR below 60 ml/min during treatment, was observed in 19% of patients. Cisplatin was administered at higher dose intensity in the 3-week schedule but this did not lead to differences in nephrotoxicity between the two schedules. Differences in reporting renal toxicities make comparisons with previously published studies difficult.

In patients with GFR 50–60 ml/min, we report the administration of cisplatin split into two doses given on day 1 and 2 to be a feasible strategy. It was tolerable and efficient with survival rates comparable to patients with a GFR ≥ 60 ml/min although eight of the 13 patients had visceral metastases. As only 13 patients had cisplatin divided in two doses on day 1 and 2, the results should be interpreted with caution. Our results may be supported by the data reported by Hussain et al. Citation[14] with a different 3-week GC schedule using cisplatin 35 mg/m2 on day 1 and 8. In that study, 19 patients had an impaired renal function (GFR of 40–60 ml/min). These patients did not experience a significant further decline in their renal function during treatment. Separate response and survival parameters for these 19 patients were not reported Citation[14].

Our results have to be interpreted with caution due to the non-randomized and retrospective design.

In our institutions GC was only applied as the presented 3-week or 4-week schedule. The choice of either the 3-week or the 4-week schedule was based on the running local protocols for that specific time period and not based on selected patient parameters. Thus during these specific time periods, all patients had the same schedule, which limits selection biases for the two schedules.

In this present material we found a significant difference in the distribution of prognostic baseline parameters with more patients with poor prognostic features in the 4-week schedule, which may favor the 3-week schedule in terms of survival and tolerability. We adjusted the HR for overall and progression-free survival and the OR for toxicity for the uneven distribution of these parameters, which did not change the conclusions of the study. However, as the study was not randomized, unknown parameters may have influenced the outcome measures.

In summary, we demonstrate that GC administered in a 3-week schedule is feasible and tolerable in locally advanced and/or metastatic bladder cancer. We found an improved compliance profile, adequate dose intensity and no differences in efficacy parameters for the 3-week schedule compared with the 4-week schedule. Thus with the proper reservations due to the retrospective data we find that the 3-week schedule may be an effective and feasible GC treatment schedule as an alternative to the 4-week schedule.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Professor Michael Vaeth, Department of Biostatistics, Institute of Public Health, University of Aarhus, Denmark for advice on survival analyses. The project was supported in part by grants from: Danish Cancer Society, Max og Inger Wörzners Fond, Frits, Georg og Marie Cecilie Gluds Fond. There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- von der Maase H, Hansen SW, Roberts JT, Dogliotti L, Oliver T, Moore MJ, et al. Gemcitabine and cisplatin versus methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin, and cisplatin in advanced or metastatic bladder cancer: Results of a large, randomized, multinational, multicenter, phase III study. J Clin Oncol 2000; 18: 3068–77

- von der Maase H, Sengelov L, Roberts JT, Ricci S, Dogliotti L, Oliver T, et al. Long-term survival results of a randomized trial comparing gemcitabine plus cisplatin, with methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin, plus cisplatin in patients with bladder cancer. J Clin Oncol 2005; 23: 4602–8

- Kaufman D, Raghavan D, Carducci M, Levine EG, Murphy B, Aisner J. Phase II trial of gemcitabine plus cisplatin in patients with metastatic urothelial cancer. J Clin Oncol 2000; 18: 1921–7

- Lorusso V, Manzione L, De Vita F, Antimi M, Selvaggi FP, De Lena M. Gemcitabine plus cisplatin for advanced transitional cell carcinoma of the urinary tract: A phase II multicenter trial. J Urol 2000; 164: 53–6

- Moore MJ, Winquist EW, Murray N, Tannock IF, Huan S, Bennett K. Gemcitabine plus cisplatin, an active regimen in advanced urothelial cancer: A phase II trial of the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group. J Clin Oncol 1999; 17: 2876–81

- Parra HS, Cavina R, Latteri F, Sala A, Dambrosio M, Antonelli G. Three-week versus four-week schedule of cisplatin and gemcitabine: Results of a randomized phase II study. Ann Oncol 2002; 13: 1080–6

- Parra HS, Cavina R, Latteri F, Campagnoli E, Morenghi E, Torri W. Cisplatin plus gemcitabine on days 1 and 4 every 21 days for solid tumors: Result of a dose-intensity study. Invest New Drugs 2007; 25: 57–62

- Burnett AF, Roman LD, Garcia AA, Muderspach LI, Brader KR, Morrow CP. A phase II study of gemcitabine and cisplatin in patients with advanced, persistent, or recurrent squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix. Gynecol Oncol 2000; 76: 63–6

- Yau TK, Lee AW, Wong DH, Yeung RM, Chan EW, Ng WT. Induction chemotherapy with cisplatin and gemcitabine followed by accelerated radiotherapy and concurrent cisplatin in patients with stage IV(A-B) nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Head Neck 2006; 28: 880–7

- Ko AH, Dito E, Schillinger B, Venook AP, Bergsland EK, Tempero MA. Phase II study of fixed dose rate gemcitabine with cisplatin for metastatic adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. J Clin Oncol 2006; 24: 379–85

- Adamo V, Magno C, Spitaleri G, Garipoli C, Maisano C, Alafaci E, et al. Phase II study of gemcitabine and cisplatin in patients with advanced or metastatic bladder cancer: Longterm follow-up of a 3-week regimen. Oncology 2005; 69: 391–8

- Huisman C, Giaccone G, van Groeningen CJ, Sutedja G, Postmus PE, Smit EF. Combination of gemcitabine and cisplatin for advanced non-small cell lung cancer: A phase II study with emphasis on scheduling. Lung Cancer 2001; 33: 267–75

- Kim JH, Lee DH, Shin HC, Kwon JH, Jung JY, Kim HJ. A phase II study with gemcitabine and split-dose cisplatin in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 2006; 54: 57–62

- Hussain SA, Stocken DD, Riley P, Palmer DH, Peake DR, Geh JI, et al. A phase I/II study of gemcitabine and fractionated cisplatin in an outpatient setting using a 21-day schedule in patients with advanced and metastatic bladder cancer. Br J Cancer 2004; 91: 844–9

- WHO handbook for reporting results of cancer treatment. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1979.

- Hryniuk WM. The importance of dose intensity in the outcome of chemotherapy. Important Adv Oncol 1988;121–41.

- Zatloukal P, Petruzelka L, Zemanova M, Kolek V, Skrickova J, Pesek M. Gemcitabine plus cisplatin vs. gemcitabine plus carboplatin in stage IIIb and IV non-small cell lung cancer: A phase III randomized trial. Lung Cancer 2003; 41: 321–31

- Brodowicz T, Krzakowski M, Zwitter M, Tzekova V, Ramlau R, Ghilezan N. Cisplatin and gemcitabine first-line chemotherapy followed by maintenance gemcitabine or best supportive care in advanced non-small cell lung cancer: A phase III trial. Lung Cancer 2006; 52: 155–63

- Flechon A, Fizazi K, Gourgou-Bourgade S, Theodore C, Beuzeboc P, Geoffrois L. Gemcitabine and cisplatin after radical cystectomy for bladder cancer in an adjuvant setting: Feasibility study from the Genito-Urinary Group of the French Federation of Cancer Centers. Anticancer Drugs 2006; 17: 705–8

- Sengelov L, Kamby C, Geertsen P, Andersen LJ, von der Maase H. Predictive factors of response to cisplatin-based chemotherapy and the relation of response to survival in patients with metastatic urothelial cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2000; 46: 357–64

- Bajorin DF, Dodd PM, Mazumdar M, Fazzari M, McCaffrey JA, Scher HI, et al. Long-term survival in metastatic transitional-cell carcinoma and prognostic factors predicting outcome of therapy. J Clin Oncol 1999; 17: 3173–81