Germ-cell tumours (GCTs) account for 2% of human malignancies, but are the most common malignant tumours in males aged 15–35. Approximately 2–5% of the GCTs arise at extragonadal sites, usually in the midline of the body, with the mediastinum and retroperitoneum as the two major sites (54 and 45% of the cases, respectively) Citation[1]. Garnick et al. reported an association between haematological malignancies and mediastinal GCTs in 1983 Citation[2] and several cases have been published since Citation[3–8]. The majority present with a mediastinal GCT and develop the haematological malignancy several months later, with a median interval of 6 months between the two diagnoses Citation[8]. We report three cases in which the haematological malignancies were concurrent with the mediastinal GCTs.

Case 1

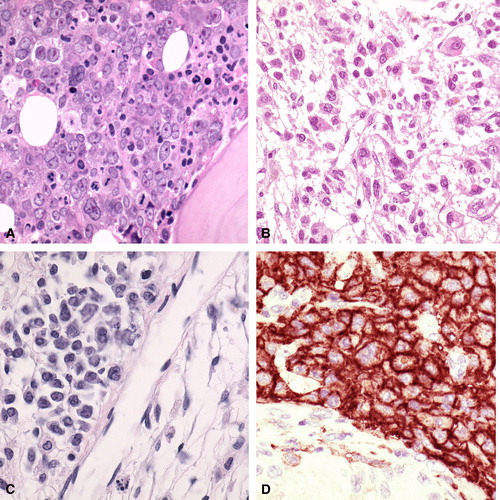

A 31-year-old male presented with fatigue, fever, weight loss, night sweating, and diffuse muscular pain. The investigation revealed anaemia, thrombocytopenia, and a mediastinal tumour (). Bone marrow trephine biopsy and aspirate showed acute megakaryoblastic leukaemia (M7) (a), whereas a mediastinal biopsy showed a GCT with embryonal carcinoma, endodermal sinus tumour, and mature teratoma components. The serum levels of alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) and human chorion gonadotropin (HCG) were elevated (). An ultrasound scan of the testicles with subsequent biopsies demonstrated bilateral leukemic infiltrates. The patient showed a partial response on cisplatin based chemotherapy and intrathecal chemotherapy (). Five months following diagnosis, however, he developed disease progression with pancytopenia and died due to an acute gastrointestinal bleeding.

Figure 1. A. Patient 1. The bone marrow trephine biopsy shows massive infiltration with megakaryoblasts (HE stain, 200×) B. Patient 3. The bone marrow shows infiltration with atypical histiocytic cells. Edema is noted in the background (HE stain, 200×) C. Patient 3. The testis biopsy shows interstitial infiltration with atypical histiocytes (HE stain, 300×). D. Patient 3. The atypical infiltrate in the testis expresses the monocyte-histiocyte marker CD14 (immunoperoxidase stain, 300×).

Case 2

A 25-year-old male presented with fatigue, fever, cough, and chest pain. The investigation showed anaemia, elevated leukocyte and platelet counts, and a mediastinal tumour (). Bone marrow aspirate and trephine biopsy were compatible with malignant histiocytosis. Fuorescence in situ hyridization (FISH) analyses demonstrated the presence of the GCT specific marker isochromosome 12p (i12p). The mediastinal tumour was a GCT with mature and immature teratoma components. AFP and HCG levels were elevated () and bilateral biopsies from atrophic testicles showed atypic cellular infiltrates, most likely leukemic. The patient received a single course of cisplatin based chemotherapy, but developed septicaemia and an acute respiratory distress syndrome and died less than a month following diagnosis.

Case 3

A 27-year-old male presented with fatigue, breathlessness at exertion, dizziness, cough, and chest pain. The investigation revealed anaemia, pancythopenia, and elevated AFP and HCG-levels (). Bone marrow trephine biopsy and aspirate showed malignant histiocytosis with haemophagocytosis (b). CT-scans demonstrated a large mediastinal tumour and lung, liver and spleen metastases. Small biopsies from the mediastinal tumour contained a partially necrotic carcinoma, compatible with teratocarcinoma. No other tumour components were seen. Based on the elevated tumour markers, the mediastinal tumour was considered most likely a nonseminomatous GCT. There were small hypoeccoic lesions in the left testicle which was removed and turned out to harbour focal infiltration of malignant histiocytosis (c and d). The patient received four courses of cisplatin based chemotherapy (). The disease, however, progressed and the patient died five months following diagnosis.

Discussion

The three cases support previous evidence of an association between haematological malignancies and mediastinal GCTs in young males. A total of 64 cases have been published Citation[2–8]. The syndrome seems to be specific for mediastinal nonseminomatous GCTs, and frequently there are serologic (elevated AFP) or histologic evidence of yolk-sac elements Citation[5], Citation[8]. It should be noted however, that there are two reports in which the GCTs were located in the testicle and in the midline of the brain, respectively Citation[9], Citation[10]. One of the three present patients suffered from acute megakaryoblastic leukaemia, the two others from malignant histiocytosis. These two, otherwise rare, diseases previously have been reported to be the most common haematological neoplasias in this syndrome Citation[5].

Haematological malignancies associated with nonseminomatous mediastinal GCTs have to be distinguished from therapy-related secondary leukemias. Leukemias caused by alkylating agents or topoisomerase II inhibitor, typically are diagnosed 5–7 and 2–3 years following therapy, respectively Citation[8]. The fact that the present three cases presented with haematological malignancy before instalment of any treatment, excludes the possibility that the haematological malignancies were therapy-related. In previous reports 5/16 and 2/17 patients with haematological malignancy and EGCT presented simultaneously with the two diagnoses Citation[5], Citation[8].

Nonseminomatous GCTs have the capacity to display totipotential differentiation, ranging from pluripotential embryonal carcinoma to extraembryonic or somatic cell types (teratomas). On rare occasions teratomas undergo malignant transformation into somatic components indistinguishable from primary malignancies like sarcoma or adenocarcinoma. Accordingly, the hematologic malignancies may well represent malignant transformation of hematopoietic tissue within the EGCTs. Supporting this hypothesis is the fact that the GCT-specific cytogenetic marker i(12p) was found in the bone marrow of patient 2 and in a few previous reported cases Citation[9], Citation[11], Citation[12].

All of the three patients had an aggressive clinical course of the disease and died within 6 months of diagnosis, in spite of cisplatin-based chemotherapy directed towards the GCT. In a previous report on 17 patients treated with cisplatin-based regimens, none were alive following two years of observation Citation[8]. Chemotherapy against teratomas with malignant transformation into nonhaematological neoplasms usually is dictated by the transformed histology. Therapeutic regimens should be designed to target the haematological malignancy as well as the GCT.

Our report underscores the importance of screening young males with haematological malignancies, especially with rare subtypes thereof, such as megakaryoblastic leukemia or malignant histiocytosis, for mediastinal GCTs. This can easily be accomplished by determining serum AFP and HCG and by performing radiological examination of the thorax. Mutatis mutandis, it seems reasonable to propose that bone marrow aspirate and trephine biopsy should be taken in all patients diagnosed with mediastinal nonseminomatous GCTs.

References

- Bokemeyer C, Nichols CR, Droz J-P, Schmoll H-J, Horwich A, Gerl A, et al. Extragonadal germ-cell tumours of the mediastinum and retroperitoneum: Results from an international analysis. JCO 2002; 20: 1864–73

- Garnick MB, Griffin JD. Idiopathic thrombocytopenia in association with extragonadal germ-cell cancer. Ann Inter Med 1983; 89: 926–7

- Helman LJ, Ozols RF, Longo DL. Thrombocytopenia and extragonadal germ-cell neoplasm. Ann Intern Med 1984; 101: 280

- Nichols CR, Hoffman R, Einhorn LH, Williams SD, Wheeler LA, Garnick MB. Haematological malignancies associated with primary mediastinal germ-cell tumours. Ann Intern Med 1985; 102: 603–9

- Nichols CR, Roth BJ, Heerema N, Griep J, Tricot G. Haematological neoplasia associated with primary mediastinal germ-cell tumours. N Engl J Med 1990; 322: 1425–9

- Ladanyi M, Roy I. Mediastinal germ-cell tumours and histiocytosis. Hum Pathol 1988; 19: 586–90

- Dulmet EM, Macchiarini P, Suc B, Verley JM. Germ-cell tumours of the mediastinum. A 30-year experience. Cancer 1993; 72: 1894–901

- Hartmann JT, Craig R, Nichols J-P, Horwich A, Gerl A, Fosså SD, et al. Hematologic disporders associated with primary mediastinal nonseminomatous germ-cell tumours. JNCI 2000; 92: 54–61

- Heimdal K, Evensen SA, Fosså SD, Hirscberg H, Langholm R, Brøgger A, et al. Karyotyping of a haematological neoplasia developing shortly after treatment for cerebral extragonadal germ-cell tumour. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 1991; 57: 41–6

- Margolin K, Traweek T. The unique association of malignant histiocytosis and a primary gonadal germ-cell tumour. Med Pediatr Oncol 1992; 20: 162–4

- RS Chaganti, M Ladanyi, Samaniego, et al. Leukemic differentiation of a mediastinal germ-cell tumour. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 1989;1:83–7.

- Ladanyi M, Samaniego F, Reuter VE, et al. Cytogenetic and immunohistochemic evidence for the germ-cellorigin of a subset of acute leukemias associated with mediastinal germ-cell tumours. J Natl Cancer Inst 1990; 82: 221–7