Abstract

Introduction. Peginterferon has an increased plasma half-life and enables a constant exposure to interferon. This modification might increase the antiangiogenic effect of the treatment and influence the efficacy. We report the results of a phase II open-label study with Peginterferon alfa-2b (Pegintron® Schering-Plough) on efficacy and tolerability in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma (MRCC). Materials and methods. Twenty eight patients with MRCC were treated with Peginterferon in escalating doses of 0.5 µg/kg once weekly until 2 µg/kg was reached or prohibited toxicity occurred. Lesions were evaluated according to Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST). Results. Thirteen patients tolerated a dose of 2 µg/kg/week. At 6 months 16 patients (57%) had disease control of which four had partial response (PR) and 12 stable disease whereas 12 (43%) had progressed. PR was only seen in the lung parenchyma or mediastinum. Median time to progression (TTP) was 8 months in all patients and 13 months for PR and SD patients. Correspondingly, median survival was 19.5 months and 28 months, respectively (seven patients received second-line treatment with tyrosine kinase inhibitor). The mean dose during long-term treatment was 1.5 and at the end of treatment 1.2 µg/kg/week. Most side effects were grade 1-2 and only two patients stopped treatment for that reason. VEGF levels in serum before and during treatment did not correlate to the therapeutic response. Discussion. Peginterferon was well tolerated in MRCC albeit with dose modification during long-term treatment. Response pattern seems to be the same as with nonpegylated interferon. Peginterferon may be used as monotherapy in selected patients and in trials of combinations with targeted drugs.

Until recently interferon alfa or IL-2 has been the main treatment option for selected patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma (MRCC) Citation[1]. Clinical trials have reported response rates of 15–20% but only about 2% complete responses among patients with MRCC Citation2–4.

Two randomised trials have shown survival benefit of interferon in comparison with medroxyprogesteron acetate Citation[1] or vinblastin Citation[5]. An improved response has also been demonstrated when interferon is combined with newly developed targeted drugs Citation[6], Citation[7].

Peg-interferon is a conjugate of interferon with polyethylene glycol (PEG). The conjugate decreases the clearance, thus prolonging the plasma half time (t½) to approximately 40 hrs (in patients with chronic hepatitis) from otherwise 3–7 hrs for not conjugated interferon alfa-2b Citation[8], Citation[9]. The prolonged plasma half-life of Peg-interferon achieves a more constant exposure which leads to an increased area under the concentration curve (AUC). This may more effectively inhibit the angiogenesis as repeated injections of low-dose interferon Citation10–12. Thereby, the efficacy of the drug may be increased as it has an antiangiogenic effect Citation[9] apart from the immunological effect. The angiogenesis is thought to play a central role in the progress of MRCC and increased Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) in serum is a negative prognostic factor Citation[13].

The pharmacokinetics of Peg-interferon allows for administration subcutaneously once weekly and this regimen has shown acceptable safety Citation[8].

Pegylated interferon has been used in different clinical settings such as hepatitis C Citation[15], chronic myelogenous leukaemia (CML) Citation[16] and malignant melanoma Citation[17]. The most efficient dosage of Peg-interferon in MRCC is still unclear and there are few studies in MRCC Citation[14], Citation[17], Citation[18].

We report the results of a phase II open-label study with Peg-interferon alfa-2b, (Pegintron® Schering-Plough) with the intention of studying tolerability and efficacy in patients with advanced MRCC.

As a marker of angiogenesis the level of VEGF in serum was measured.

Material and methods

Eligibility

Patients with progressive metastatic renal cell carcinoma, MRCC, not curable with surgery were studied. A single target lesion should measure ≥20 mm in diameter and ≥10 mm in diameter if multiple lesions. Prior immunotherapy was not allowed. The patient should preferably have been nephrectomised but that was not a requirement, minimum age 18 years with a life expectancy of at least 3 months. The patient should have adequate haematological, renal and hepatic function when enrolled: HB ≥100 g/L, WBCC ≥ 3.0×109, Platelets ≥100×109, Bilirubin/s ≤30 µmol/L, Creatinine/s ≤180 µmol/L. Patients with clinical evidence of CNS metastasis were not eligible. Patients with performance status of Easter Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) > 1 were not compatible with eligibility. All patients signed a written consent.

Patient characteristics ()

Twenty-eight patients were recruited between January 2002 and October 2005 and followed up until November 2008. The majority of the patients had >1 metastatic site. Eleven patients were diagnosed with MRCC limited to the lungs, two of whom also had mediastinal metastases.

Table I. Patient characteristics at baseline.

Dose, treatment and management

Peg-interferon alfa-2b was administrated subcutaneously at a starting dose of 0.5 µg/kg/w and was escalated in increments of 0.5 µg/kg every two weeks until a dose of 2 µg/kg/w was reached or prohibitive toxicity occurred. Treatment was continued at maximum tolerable dose (MTD), until progression of disease. Doses were adjusted to allow for long-term treatment with acceptable side effects and quality of life. The patients were instructed by a nurse and given written instructions in order to administrate the treatment themselves.

Adverse events were graded for severity according to the National Cancer Institute's common toxicity criteria (NCI-CTC version 3.0) classification. Adverse events were managed by dose reduction until resolved (grade 0-1), at which time the dose was to be increased to MTD.

Response and evaluation

Computerised tomography (CT) of abdomen and thorax was performed every 3 months and reviewed by an independent radiologist. Tumour response was calculated according to RECIST Citation[19]. Confirmation of stable disease (SD) and partial response (PR) was set to 6 months after the first dose of Pegintron®, thus two consecutive image investigations were required.

VEGF analysis

Blood samples for analysis of VEGF were collected prior to first Pegintron® dose and every month throughout the treatment. The serum samples were stored at –80°C until analysis. This was performed according to the established technique, using a commercial quantitative immunoassay kit for human VEGF165 (Quantikine®, Human VEGF immunoassay, R & D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) Citation[13]. Briefly, 100 µL of the serum samples diluted in 100 µL buffer solution or serially diluted standard solution (human VEGF) were added to a 96-well microtiter plate pre-coated with mouse anti-human VEGF monoclonal antibody and incubated at room temperature for 2 hours. After washing, 200 µL of the secondary antibody solution, a VEGF specific polyclonal goat antibody was incubated for 2 hours at room temperature. Substrate solution was added and the reaction continued for 25 minutes. Optical density was determined on a microtiter plate reader (Multiskan MCC/340, Labsystems) at 450 nm.

Statistical methods

The Gehan two-step procedure was used to determine the size of the material Citation[20]. Initially, 14 patients were treated and accrual of further patients to the study continued if one responding patient was seen among the first 14 patients. Under these conditions the probability of rejecting a treatment with a response rate of 20% was less than 5%.

Response rates and adverse events were analysed with descriptive statistics. Survival rate was estimated with the Kaplan-Meier method. The non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test was used for testing the differences between groups.

Results

Dose ()

Thirteen patients (46%) managed to reach a weekly dose of 2 µg/kg. Nine patients (32%) reached the interval of ≥1.5 < 2.0 µg/kg/week and two patients the interval of ≥1.0 < 1.5 µg/kg. Thirteen of twenty eight patients (46%) needed a dose reduction at some time.

Table II. Number of patients on each interval of maximum reached dose and number of patients having their dose reduced at some time during the study.

Sixteen patients continued the treatment for 6 months or longer and of these 11 (69%) needed dose reduction at some stage. One of these is still on the treatment. This subgroup had an average dose of 1.5 µg/kg/weekly for the entire treatment period. Among these 16 patients the dose at the end of the treatment was average 1.2 µg/kg/weekly. The 12 patients that were assessed as PD < 6 months had an average dose of 1.1 µg/kg/weekly. Four of these never reached 1.0 µg/kg/weekly.

Totally 24 patients managed to reach ≥1.0 µg/kg/weekly at some time.

Toxicity ()

The most common side effects reported throughout the study were fatigue, nausea, fever and rigor/chills mostly grade 1-2 according to NCI-CTC. In the long term there were also reports of skin-rash, anorexia and weight loss.

Table III. Toxicity was registered according to NCI-CTC version 3.0. No grade 4 events were reported. Early side effects were assessed during the first two months giving the patients a chance of reaching 2 µg/kg/week.

There were four grade 3 adverse events, concerning cardiac-dysrhythmia, anorexia, fatigue and bleeding in the eye. No grade 4 adverse event was registered.

Two patients stopped treatment due to toxicity; bleeding in the eye and several simultaneous grade 2 toxicities respectively. Due to elevated ALAT (>2.5×upper reference limit) two patients temporarily reduced the dose of Pegintron. One of the patients with elevated ALAT also had elevated creatinine (>200 µmol/L) which subsided with the dose reduction. Another patient also indicated impaired renal function with elevated creatinine which was improved after dose reduction.

Response and survival

At 6 months four patients (14%) were evaluated having a PR. No PR was observed later in the treatment. SD was assessed in 12 patients (43%) at 6 months and in 8 patients (29%) at 12 months. Twelve patients (43%) had progressive disease (PD) at 6 months, out of which 6 had PD at 3 months.

Time to progression (TTP) in all patients was median 8 (1–40 + ) months (). TTP in patients with disease control (PR and SD) was 13 months.

Figure 1. Kaplan-Meier curve for time to progression (TTP), n = 28. Median TTP 8 months for the entire study population. One patient had not reached PD at the time of evaluation. Censored patient is shown by a vertical tick mark.

In the subgroup of PR and SD, 14/16 (88%) patients had performance status (PS) ECOG 0 and 7 (44%) patients had only one metastatic site. The corresponding data for the group of PD <6 months were 7/12 (58%) with ECOG 0 and 2/12 (17%) patients with one metastatic site respectively ().

Table IV. Patient characteristics at baseline for those responding with partial response (PR), reaching stable disease (SD) or progressive disease (PD) within six months.

After discontinuing Pegintron® seven patients received second-line treatment with targeted drugs and seven endocrine treatment with Tamoxifen.

The median overall survival (n = 28) was 19.5 (1–88.5) months (). In patients with disease control (PR and SD) the survival was median 28 (15–88.5) months, six of those received second-line targeted drugs. Five patients are still alive, three after targeted treatment, one is still on Pegintron and has not yet progressed. One patient has progressed with liver metastases which have been treated with radio frequency ablation. In patients with PD <6 months the median overall survival was 9.3 (1–30) months, one of these patients received targeted drugs.

Figure 2. Kaplan-Meier survival curve, until November 2008, n = 28. Median overall survival was 19.5 months. Totally five patients were still alive. Three of these received second-line treatment with targeted drugs. Censored patients are shown by vertical tick marks.

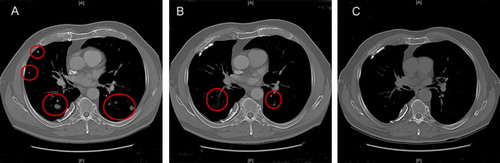

Patients with only pulmonary and mediastinal metastases (n = 11) had a median TTP of 9.5 (3–32 + ) months and a response rate of 4/11 (36%) with PR at 6 months and median survival of 25.5 (9–33) months () ().

Figure 3. Average VEGF in serum (pg/ml). Levels of VEGF did not correlate to the therapeutic response.

Figure 4. Computed tomography of a patient with lung metastases responding (PR) to treatment. Baseline, A. Three months, B. Ten months, C.

Table V. Patient characteristics at baseline for patients with only lung and/or mediastinal metastases.

Twenty-two patients were eligible for MSKCC risk evaluation with five patients favourable, 16 intermediate and one patient with poor prognosis. The favourable had a survival of median 33 months and those with intermediate risk 13.5 months. Corresponding data for TTP were 15.5 and 4 months respectively.

S-VEGF ()

The pre-treatment s-VEGF was 594 (85–1 742) pg/ml in the overall group, 565 (128–1 575) pg/ml in the disease control group and 632 (97–1 742) pg/ml in the non-responders’ group, NS.

During treatment there was no statistical significance between patients with PR and SD, versus non-responders. In the group of non-responders the s-VEGF was only followed for 3 months compared with 12 months in the other group.

Discussion

Treatment with Interferon alfa-2b for MRCC, given three times weekly, results in an oscillating plasma concentration, apart from the inconvenience for the patients with repeated injections. In the present study we used Pegintron® with the intention of finding an acceptable dose for long-term treatment (≥6 months) and still reaching clinical benefit as with conventional IFN alpha 2b treatment.

Polyethylene glycol (PEG) is a neutral, flexible polymer that is used to modify proteins. Studies investigating several proteins with added PEG have shown longer plasma-lives, lower immunogenicity, improved water solubility and less sensitivity to proteolysis. PEG has also a well-known safety record. Through conjugating PEG with interferon alfa-2b (IFN-α2b), PEG-intron (Pegintron®, Schering-Plough AB) the achievements of longer plasma half-life (around 40 hours) in patients with normal renal function Citation[21] and weekly injections are reached compared to using IFN-α2b alone with a half-life of 3–7 hours.

As this was not a randomised study we decided to classify clinical benefit as partial response, PR, and stable disease, SD, only when RECIST was fulfilled from baseline to 6 months, to get more robust data.

In our study with Pegintron® the overall response rate (PR) was 14% (at 6 months) and 43% had SD. At 12 months 29% (n = 8) were still assessed as SD and two patients were still at SD after 24 months.

The median overall survival was 19.5 (1–88.5) months (after second-line treatment with TKI in seven patients) and at one year 71% of the patients were still alive. These data are in line with former phase I/II trials Citation[10], Citation[17], Citation[18]. However, in those studies the patients were treated with pegylated interferon alfa-2b doses of 4.5–7.5 µg/kg/week. One of the studies Citation[18] contained patients with MRCC where all (100%) had been subject to nephrectomy, in comparison to our group where 5/28 (18%) never were under surgery. Another study Citation[17] was a mixed study-population with different solid tumours even though most of them were MRCC, several of whom had received previous treatment. Both of those studies presented patients with CR but also more frequently severe adverse events. We have here presented the results from treating a group of severely ill patients from MRCC, treated with low average-dose of Peg-interferon (1.5 µg/kg/w among those who stayed on the treatment for ≥6 months) and still reaching acceptable response and minimising the toxicity.

In a randomised study (n = 100), two different dosing regimens of IFN (interferon alfa-2a) were tested in combination with Sorafenib, IFN 9 MU three times weekly versus 3 MU five times weekly. The latter (low-dose IFN) gave similar response as to that of the higher IFN dose Citation[6].

Bevacizumab, in combination with IFN-α2a, suggests in subgroup analysis that IFN can be reduced in order to manage side effects but still maintaining efficacy Citation[22].

The baseline characteristics of the patients with PR or SD (n = 16) contains a larger proportion of patients with only one metastatic site (n = 7) and more frequently ECOG 0 (n = 14) than among the patients of PD < 6 months. These data could be expected concerning prognostic factors and are in accordance with a previously performed interferon study Citation[23].

In the group of patients with only lung metastases TTP was 9.5 months, median survival 25.5 and four of 11 patients (36%) had PR. Increased survival has been demonstrated in lung metastases compared to other metastatic sites during interferon treatment of MRCC irrespectively if nephrectomy was performed or not Citation[24].

In our study population 21 patients had ECOG 0, their median TTP was 10 (1–32) months and survival 25.5 (3–88.5) months. In the group of patients with ECOG 1 (n = 7), their median TTP was 3 (1–15) and survival 9.5 (1–19.5) months.

Four patients progressed (PD) after one month only. Two of those had a performance status (PS) of ECOG 1. All four had either two or three metastatic sites. Previous trials have shown high ECOG Citation[25], Citation[26] and number of metastatic sites a negative prognostic factor Citation[27].

VEGF in serum taken before planned nephrectomy has a prognostic value in RCC Citation[12] but in MRCC a significant increased survival with low s-VEGF was shown only in patients with the best PS Citation[28]. In our study pre-treatment s-VEGF had no prognostic value. During treatment with peginterferon no difference could be demonstrated between responders and non-responders, hence VEGF in serum appears not to be a useful serum marker to monitor interferon treatment in patients with MRCC.

To designate the early or late adverse events, toxicity was analysed at 2 months to give the patients a chance to reach full dose. Toxicity, grade 3/4 was very rare. Only two patients left the study due to side effects, bleeding in the eye and the other due to several grade two effects simultaneously. However, dose reduction at some time during the study was frequent, 13/28 (46%), and four patients never even reached the dose of 1.0 µg/kg/weekly before discontinuing the study. Considering the low doses of Pegintron® we administered, the dose reduction reflects the clinical assessment by the physician of the patient in tailoring the treatment. Previous studies have shown a link between low dose IFN and the reduction of toxicity Citation[29]. However, one could speculate that diminishing side effects may also erase the drug efficacy. The optimal dose for treating patients with MRCC is still not known, however we have in our study population a group of 16 patients that had clinical benefit of the treatment. Those were treated with an average dose of 1.5 µg/kg/week.

Pharmacokinetic studies on pegylated interferon, analysing accumulation, have been performed with interferon alpha 2a and in combination with other drugs and in clinical settings such as Chronic Hepatitis C (CHC) Citation[8], Citation[21]. For doses of 0.7–1.4 µg/kg administrated weekly a slight accumulation was observed over one month calculating from the area under the curve of concentration (AUC). However, the main part of our study group had been subject to nephrectomy and the pharmacokinetics may be different than in patients with CHC. T½ is prolonged if the renal function decreases to CLcr to 20–40 mL/min Citation[30] which is not unusual in nephrectomised patients. Thus drug accumulation cannot be excluded in our patient material during long-term treatment. Late appearing side effects which called for dose reduction could support this hypothesis. However, we were not able to analyse plasma concentration of peginterferon.

In the era of TKIs we see combination trials and sequential trials in treating MRCC. One combination in different trials is TKI + IFN. The prolonged exposure with pegylated interferon mimic the repeated injection of interferon and may increase the antiangiogenic effect of the drug. Our results indicate that Peginterferon may be used as monotherapy in selected patients and in trials of combination with targeted drugs.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by King Gustav V Jubilée Clinic Cancer Research Foundation, The Göteborg Medical Society′s grant number 07/9248, The Foundation of Anna-Lisa and Bror Björnsson, The Foundation of Märtha and Gustaf Ågren at the Department of Urology, Sahlgrenska University Hospital and by Schering-Plough Ltd. Declaration of interest: The authors report no other conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Collaborators MRCRC. Interferon-alpha and survival in metastatic renal carcinoma: Early results of a randomised controlled trial. Medical Research Council Renal Cancer Collaborators. Lancet 1999;353:14–7.

- Quesada JR, Rios A, Swanson D, Trown P, Gutterman JU. Antitumor activity of recombinant-derived interferon alpha in metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 1985; 3: 1522–8

- Figlin RA, deKernion JB, Mukamel E, Palleroni AV, Itri LM, Sarna GP. Recombinant interferon alfa-2a in metastatic renal cell carcinoma: Assessment of antitumor activity and anti-interferon antibody formation. J Clin Oncol 1988; 6: 1604–10

- Wirth MP. Immunotherapy for metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Urol Clin North Am 1993; 20: 283–95

- Pyrhonen S, Salminen E, Ruutu M, Lehtonen T, Nurmi M, Tammela T, et al. Prospective randomized trial of interferon alfa-2a plus vinblastine versus vinblastine alone in patients with advanced renal cell cancer. J Clin Oncol 1999; 17: 2859–67

- Bracarda, S ECea. Sorafenib plus interferon alpha-2b in metastatic renal cell carcinoma: Results from RAPSODY (GOIRC Study 0681)-A randomized prospective Phase II Trial of two different treatment schedules. EAU 2008-23rd Annual EAU Congress. 2008.

- Escudier B, Pluzanska A, Koralewski P, Ravaud A, Bracarda S, Szczylik C, et al. Bevacizumab plus interferon alfa-2a for treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma: A randomised, double-blind phase III trial. Lancet 2007; 370: 2103–11

- Glue P, Fang JW, Rouzier-Panis R, Raffanel C, Sabo R, Gupta SK, et al. Pegylated interferon-alpha2b: Pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, safety, and preliminary efficacy data. Hepatitis C Intervention Therapy Group. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2000; 68: 556–67

- Wang YS, Youngster S, Grace M, Bausch J, Bordens R, Wyss DF. Structural and biological characterization of pegylated recombinant interferon alpha-2b and its therapeutic implications. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2002; 54: 547–70

- Motzer RJ, Rakhit A, Thompson J, Gurney H, Selby P, Figlin R, et al. Phase II trial of branched peginterferon-alpha 2a (40 kDa) for patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma. Ann Oncol 2002; 13: 1799–805

- Chang E, Boyd A, Nelson CC, Crowley D, Law T, Keough KM, et al. Successful treatment of infantile hemangiomas with interferon-alpha-2b. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 1997; 19: 237–44

- Berg WJ, Divgi CR, Nanus DM, Motzer RJ. Novel investigative approaches for advanced renal cell carcinoma. Semin Oncol 2000; 27: 234–9

- Jacobsen J, Rasmuson T, Grankvist K, Ljungberg B. Vascular endothelial growth factor as prognostic factor in renal cell carcinoma. J Urol 2000; 163: 343–7

- Motzer RJ, Rakhit A, Ginsberg M, Rittweger K, Vuky J, Yu R, et al. Phase I trial of 40-kd branched pegylated interferon alfa-2a for patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2001; 19: 1312–9

- Liu CH, Liang CC, Lin JW, Chen SI, Tsai HB, Chang CS, et al. Pegylated interferon alpha-2a versus standard interferon alpha-2a for treatment-naive dialysis patients with chronic hepatitis C: A randomised study. Gut 2008; 57: 525–30

- Michallet M, Maloisel F, Delain M, Hellmann A, Rosas A, Silver RT, et al. Pegylated recombinant interferon alpha-2b vs recombinant interferon alpha-2b for the initial treatment of chronic-phase chronic myelogenous leukemia: A phase III study. Leukemia 2004; 18: 309–15

- Bukowski R, Ernstoff MS, Gore ME, Nemunaitis JJ, Amato R, Gupta SK, et al. Pegylated interferon alfa-2b treatment for patients with solid tumors: A phase I/II study. J Clin Oncol 2002; 20: 3841–9

- Bex A, Mallo H, Kerst M, Haanen J, Horenblas S, de Gast GC. A phase-II study of pegylated interferon alfa-2b for patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma and removal of the primary tumor. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2005; 54: 713–9

- Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, Wanders J, Kaplan RS, Rubinstein L, et al. New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, National Cancer Institute of the United States, National Cancer Institute of Canada. J Natl Cancer Inst 2000; 92: 205–16

- Gehan EA. The determination of the number of patients required in a preliminary and a follow-up trial of a new chemotherapeutic agent. J Chronic Dis 1961; 13: 346–53

- Glue P, Rouzier-Panis R, Raffanel C, Sabo R, Gupta SK, Salfi M, et al. A dose-ranging study of pegylated interferon alfa-2b and ribavirin in chronic hepatitis C. The Hepatitis C Intervention Therapy Group. Hepatology 2000; 32: 647–53

- Melichar B, Koralewski P, Ravaud A, Pluzanska A, Bracarda S, Szczylik C, et al. First-line bevacizumab combined with reduced dose interferon-{alpha}2a is active in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Ann Oncol 2008; 19: 1470–6

- Fossa S, Jones M, Johnson P, Joffe J, Holdener E, Elson P, et al. Interferon-alpha and survival in renal cell cancer. Br J Urol 1995; 76: 286–90

- Flanigan RC, Salmon SE, Blumenstein BA, Bearman SI, Roy V, McGrath PC, et al. Nephrectomy followed by interferon alfa-2b compared with interferon alfa-2b alone for metastatic renal-cell cancer. N Engl J Med 2001; 345: 1655–9

- Elson PJ, Witte RS, Trump DL. Prognostic factors for survival in patients with recurrent or metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Res 1988; 48: 7310–3

- Fossa SD, Kramar A, Droz JP. Prognostic factors and survival in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with chemotherapy or interferon-alpha. Eur J Cancer 1994; 30A: 1310–4

- Negrier S, Escudier B, Gomez F, Douillard JY, Ravaud A, Chevreau C, et al. Prognostic factors of survival and rapid progression in 782 patients with metastatic renal carcinomas treated by cytokines: A report from the Groupe Francais d'Immunotherapie. Ann Oncol 2002; 13: 1460–8

- Alamdari FI, Rasmuson T, Grankvist K, Ljungberg B. Angiogenesis and other markers for prediction of survival in metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Scand J Urol Nephrol 2007; 41: 5–9

- Quesada JR, Talpaz M, Rios A, Kurzrock R, Gutterman JU. Clinical toxicity of interferons in cancer patients: A review. J Clin Oncol 1986; 4: 234–43

- Gupta SK, Pittenger AL, Swan SK, Marbury TC, Tobillo E, Batra V, et al. Single-dose pharmacokinetics and safety of pegylated interferon-α2b in patients with chronic renal dysfunction. J Clin Pharmacol 2002; 42: 1109–15