Abstract

Background: Lung cancer (LC) is the leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide, including Sweden. Several studies have shown that socioeconomic status affects the risk, treatment, and survival of LC. Due to immigration after Second World War, foreign-born people constitute 12.5% of the Swedish population. We wanted to investigate if there were any differences in LC management, treatment and survival among the foreign-born Swedes (FBS) compared to the native Swedish population (NatS) in Stockholm.

Material and methods: A retrospective analysis of all patients diagnosed with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) at the Department of Respiratory Medicine and Allergy, Karolinska University Hospital, Solna from 1 January 2003 to 31 December 2008 was made. In all, 2041 cases of LC were diagnosed, thereof 1803 with NSCLC. Of these, 211 (11.7%) were FBS.

Results: The mean age of NatS and FBS patients was 69.9 years, median 70 (range 26–96) and 66.0 years, median 66 (range 38–94), respectively (p < 0.001). In all, 89.8% of NatS and 90.0% of FBS were either smokers or former smokers. Adenocarcinoma was the most common subtype in both groups (NatS 54.7%, FBS 48.3%). In 140 (8.8%) of the NatS and 17 (8.1%) of the FBS the diagnosis was clinical only. There were no significant differences in stage at diagnosis, nor in performance status (PS) or different therapies between the groups. The median overall survival time for the NatS was 272 days and for FBS 328 days, again no significant difference. However, the median overall survival time for female NatS was 318 days and for female FBS 681 days (p = 0.002).

Conclusion: FBS patients were significantly younger than NatS at diagnosis, and female FBS lived longer than female NatS, but otherwise there were no significant differences between NatS and FBS patients with LC regarding diagnosis, treatment, and survival.

International immigration increased considerably in the last decades of the 20th century because of people escaping war, poverty, political, economic, and religious repression. With the settlement of hundreds of thousands of refugees from the Middle East, Africa, Asia, Latin America, Eastern Europe and the Balkans during recent decades, patients from ethnic minorities have become common in Sweden: 12.4% in 2006 and 15.9% in 2013 (Statistical yearbook of Sweden). The mean population of all Stockholm in 2008 was 1 995 917 inhabitants (Cancer Incidence in Sweden 2008), of these approximately just over 1 million inhabitants have Karolinska University Hospital, Solna, as their specialist hospital. In 2003, 18.3% of Stockholm community were FBS and the figures for 2008 were 20.0%.

A growing body of research has found that some immigrant groups have poorer health than the majority population. This has been shown for coronary heart disease [Citation1,Citation2] and in mental disorders [Citation3–8]. In some groups of immigrants a poor self-rated health has been demonstrated [Citation9,Citation10]. Some studies have also described important differences in the treatment of minority patients in some specialties in comparison with patients from the majority population [Citation11,Citation12].

Lung cancer (LC) is the leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide. Several studies have shown that the risk of developing LC is associated with socioeconomic status [Citation13,Citation14]. Race, ethnicity and social factors have been previously identified in multiple studies as variables that can account for variations in LC treatment and survival [Citation15–18] and a Swedish study has shown that socioeconomically disadvantaged groups with NSCLC receive less specialized care [Citation19]. The incidence of this cancer is associated with socioeconomic position (SEP) [Citation20]. In a recent systematic review and meta-analysis, LC patients of low SEP were less likely to receive surgery and chemotherapy in both universal and non-universal healthcare systems, regardless of stage or histology [Citation21]. Recently a Danish study [Citation22] showed that social inequalities in stage at diagnosis, comorbidity and receipt of treatment contribute to the poorer outcomes in the large group of patients who have short education, low income and live alone. Social inequality might affect other outcomes after LC, such as access to supportive care and rehabilitation [Citation23].

The exact underlying mechanisms of these social inequalities are unknown, but differences in access to care, comorbidity and lifestyle factors may all contribute. There might also be ethnic differences in awareness of cancer warning signs or help-seeking behavior.

The aim of this study was to evaluate if there are any differences in LC management, treatment and survival between the foreign-born Swedes (FBS) and to the native Swedish population (NatS).

Material and methods

This was a single-center, retrospective cohort study in all patients newly diagnosed with NSCLC in the Department of Respiratory Medicine and Allergy at the Karolinska University Hospital in Solna, Stockholm, for a six-year period from 1 January 2003 to 31 December 2008. The Stockholm-Gotland Cancer Registry was used to identify the patients. This registry is known for its high level of completeness of the data reporting. Data about all the patients newly diagnosed with LC during the above period has been extracted from the Stockholm-Gotland Cancer Registry. All the patients has been investigated and evaluated at the same department. Medical journals were reviewed, in identified patients, to get information about treatment.

The following variables were included in the analysis: age, gender, smoking history, performance status (PS) according to WHO, TNM stages [Citation24], type of LC, different types of treatment, first-, second- and third line chemotherapy, adjuvant chemotherapy and overall survival.

Patients were classified as never smokers, current, or ex-smokers. Patients who had stopped smoking for more than one year were classified as ex-smokers. Definite diagnosis was aimed at with a biopsy and/or a cytology test to verify the diagnosis and classify the tumor according to the WHO system [Citation25]. Investigations for a primary site, final clinical diagnosis and surgical and/or medical treatment for the LC were recorded.

Statistical analysis

Statistics software SPSS (version 22.0) was used for all study analyses. Patient characteristics at point of diagnosis were summarized using standard descriptive statistics. Observed frequencies in categorical variables were calculated. Survival time after diagnosis was analyzed using Kaplan-Meier estimates, and differences in survival distributions for different patient subgroups were tested using log-rank tests. Differences in categorical variables between subgroups were statistically tested using Fishers exact test, using Monte Carlo simulation with 20 000 replicates for variables with more than two categories. The significance level was set at 0.05 for all statistical tests.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Karolinska Institutet 2005/115 and 2015/2:10.

Results

In all, a total of 2041 patients were newly diagnosed with LC from 2003 to 2008 in our department. Of these, 238 (11.6%) had small cell lung cancer (SCLC) and were excluded from this study. Among the SCLC group were 204 (85.7%) NatS. Thus, 1803 patients with NSCLC remained, and of those 211 (11.7%) were FBS. All cytology and biopsies were analyzed at the Department of Pathology, Karolinska University Hospital, Solna. In all, 44 (3.3%) of the FBS were from other Nordic countries, 39 (1.5%) from west Europe, 49 (2.3%) from central Europe and the rest were spread with a couple of patients from all over the world.

The mean age in NatS patients was 69, median 70 and range 26–96 years. The figures for the immigrants was 66, median 66 and range 38–94 years, respectively (p < 0.001) (). The median age and the range for SCLC NatS and FBS were 69.0 and 62–75 years, 61.5 and 55–67.8 years, respectively.

Table 1. Patient characteristics.

Data about smoking history were available for all except 12 patients. 89.8% of the NatS and 90.0% of FBS were either smoker or former smoker (). There was no significant differences between the groups (p = 0.6465). There were a significant deference in smoking habits between genders, 18 (25%) of the female FBS and 102 (12.1%) of the female NatS were never smokers, the figures for the male patients were three (2.2%) and 60 (8.1%), respectively.

In one patient, staging was not possible. Of the remaining patients with NSCLC, 22.9% of the NatS and 21.3% of the FBS were diagnosed as stage I, 3.5% vs. 6.1% as stage II, 10.3% vs. 6.6% as stage IIIa and 63.3% vs. 65.9% as stage IIIB/IV (p = 0.2994) ().

Of the NatS 85.0% and of the FBS 84.0% had PS 0–2, 15.1% and 16.7% had PS 3–4, respectively (p = 0.4777) ().

In 140 (8.8%) NatS and 17 (8.1%) FBS the diagnosis was clinical (without histological diagnosis), because of age, lung function or radiological findings, the risks entailed by further investigation were considered to outweigh any potential therapeutic benefit. Adenocarcinoma was the most common subtype found in both groups, 54.7% and 48.3%, squamous cell carcinoma 18.7% and 22.3%, and low differentiated LC 13.4% and 15.2% for NatS and FBS, respectively (p = 0.4469) (). There were not any differences in diagnostic staging between the groups.

Table 2. Subtypes of lung cancer.

Chemotherapy was given to 502 (39.9%) of the NatS and 65 (30.9%) of the FBS, concomitant chemoradiotherapy to 134 (10.9%) and 22 (14.7%), radiotherapy against the tumor in 8.4% and 8.1%, stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) to 3.5% and 1.9%, respectively. Surgery was performed among 19.0% of the NatS and 22.0% of the FBS, and 8.1% and 7.6%, respectively, were given adjuvant chemotherapy. Approximately 22.5% of the NatS and 18.0% of the FBS received only palliative care because of poor PS, comorbidities, and/or poor lung function (). Thus, there were no significant differences in treatment between the two groups (p = 0.165). There were no significant differences in adjuvant chemotherapy between the two groups.

Table 3. Treatment modalities (p = 0.165).

Second line therapy was given to 17.3% of the NatS and 19.5% to FBS (NS). The figures for third line were 7.9% vs. 8.1%.

Survival

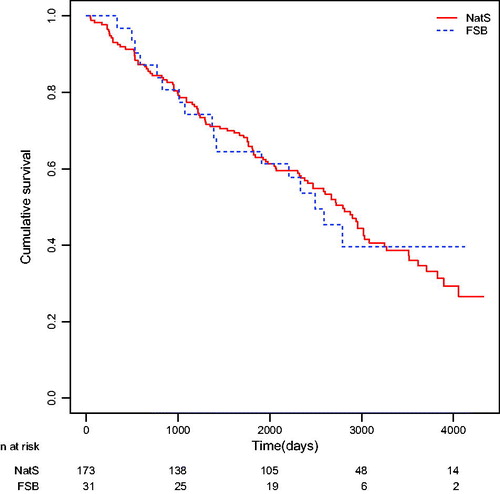

The median survival time for the NatS was 272 days with a 95% confidence interval (CI) of (246, 295), and for the FBS it was 328 days with a 95% confidence interval of (270, 435), based on 1592 Swedish patients and 209 immigrant patients. Testing the null hypothesis of equal survival distribution by the log-rank test resulted in a p-value of p = 0.1463 (). Thus, there was no statistical significant difference. The log-rank test is more powerful to detect differences in the end of the time span. The Kaplan-Meier estimates of cumulative survival plotted against time is shown in .

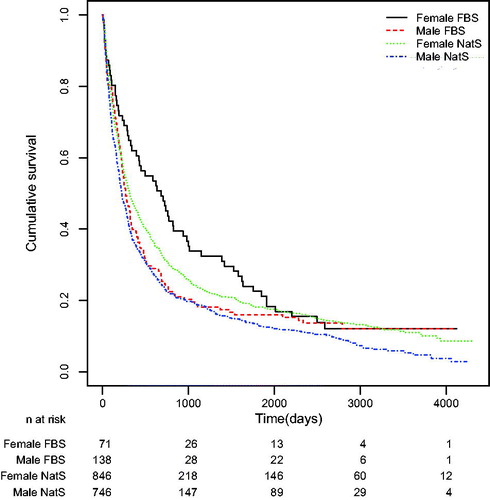

For NatS female patients the median survival time was 318 days, 95% CI (281, 368) (n = 846) and for female FBS it was 681 days, 95% CI (422, 981) (n = 71). There was thus a statistically significant difference in the survival (log-rank test resulted in a p-value of p = 0.002) (.

For males, NatS had a median survival time of 222 days, 95% CI (201, 266) (n = 746) and for FBS it was 270 days, 95% CI (224, 337) (n = 138). The log-rank test resulted in a p-value of p = 0.160.

For NatS who underwent surgery without adjuvant chemotherapy the median survival time was 7.8 years, 95% CI (6.6, 8.5) (n = 173) and for FBS it was 6.8 years 95% CI (3.9, NA) (n = 31). Due to the small number of patients at risk and the method to calculate standard errors and CIs the upper limit of the CI was not available. The log-rank test resulted in a p-value of 0.9825. For the surgical NatS who were given adjuvant chemotherapy the median survival time was 6.6 years and for the FBS the median survival time was not estimable due to more than 50% of the patients were still alive at the end of follow-up. The time point where 50% of the patients were alive was never reached. The small number of patients at risk made the estimate of the survival function uncertain (p = 0.56).

For NatS patients with stage IV the median survival time was 137 days, 95% CI (121, 157) (n = 609) and for the FBS it was 133 days, 95% CI (88, 192) (n = 85). There was thus a statistically significant difference in the survival (log-rank test, p = 0.03125).

Median survival for NatS given concomitant chemoradiotherapy was 493 days, 95% CI (417, 699) (n = 134) and for the FBS 744 days, 95% CI (509, 1623) (n = 22) (log-rank test, p = 0.7323).

Discussion

This is the first study in Sweden that in details evaluate epidemiology, treatment and survival between NatS and FBS patients with NSCLC. In this study, we used cohort of patients with LC (except SCLC), with focus on ethnicity, to determine whether racial/ethnic disparities exist in histology, smoking habits, staging, treatment and survival.

For the first generation FBS many cancer rates, such as those for stomach, LC and melanoma, have been shown to be closer to the rates of country of origin than those for Sweden. The Swedish incidence rates for all cancer are generally high compared with other countries, but the overall rates for FBS men and women regarding LC are not much lower with SIRs being 0.95 and 0.92, respectively [Citation26].

Several studies have revealed differences in health issues between NatS and FBS. In Sweden a higher incidence of mental disorders, self-reported anxiety, and severe pain has been reported in FBS than in the majority population, resulting in more prescribed analgesics and antidepressants [Citation8,Citation27,Citation28]. Unhealthy behavior, such as smoking, physical inactivity and obesity, and consequently higher risks of CHD, has been reported to be more prevalent in several immigrant groups [Citation29–32].

In the present study, the mean age at diagnosis in the FBS group was significantly lower. This is probably due to heavier smoking habits and perhaps also other environmental and lifestyle risk factors. Somewhat surprisingly against the background of earlier studies, we could not find any differences in staging, treatment or survival between NatS and FBS, except that FBS women lived significantly longer than the NatS women. This finding might be due to less intense smoking habits in the FBS women. Cultural differences can explain the low number of never smokers among the female FBS. The observed lack of differences between the NatS and FBS LC patients indicates that the FBS have as good access to health care and also are treated with the same quality of care as do the NatS, at least in the Stockholm area.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to Per Liv, Statistician at Center for Research and Development, Uppsala University/County Council of Gävleborg for valuable support and analyzing all our data.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Sundquist J, Johansson SE. Indicators of socio-economic position and their relation to mortality in Sweden. Soc Sci Med 1997;45:1757–66.

- Salmond CE, Prior IA, Wessen AF. Blood pressure patterns and migration: a 14-year cohort study of adult Tokelauans. Am J Epidemiol 1989;130:37–52.

- Eitinger L, Grunfeld B. Psychoses among refugees in Norway. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1966;42:315–28.

- Hitch PJ, Rack PH. Mental illness among Polish and Russian refugees in Bradford. Br J Psychiatry 1980;137:206–11.

- Sundquist J. Ethnicity as a risk factor for consultations in primary health care and out-patient care. Scand J Prim Health Care 1993;11:169–73.

- Cantor-Graae E, Pedersen CB, McNeil TF, et al. Migration as a risk factor for schizophrenia: a Danish population-based cohort study. Br J Psychiatry 2003;182:117–22.

- Saraiva Leao T, Johansson LM, Johansson SE, et al. Incidence of mental disorders in second-generation immigrants in sweden: a four-year cohort study. Ethn Health 2005;10:243–56.

- Leao TL, Sundquist J, Frank G, et al. Incidence of Schizophrenia or other psychoses in first- and second-generation immigrants: a national cohort study. J Nerv Ment Dis 2006;194:27–33.

- Zolkowska K, Cantor-Graae E, McNeil TF. Increased rates of psychosis among immigrants to Sweden: is migration a risk factor for psychosis? Psychol Med 2001;31:669–78.

- Wiking E, Johansson SE, Sundquist J. Ethnicity, acculturation, and self reported health. A population based study among immigrants from Poland, Turkey, and Iran in Sweden. J Epidemiol Community Health 2004;58:574–82.

- Sungurova Y, Johansson SE, Sundquist J. East-west health divide and east-west migration: self-reported health of immigrants from Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union in Sweden. Scand J Public Health 2006;34:217–21.

- Fernando S, ed. Race and Culture in Psychiatry. London: Routledge; 1988.

- Eaker S, Halmin M, Bellocco R, et al. Social differences in breast cancer survival in relation to patient management within a National Health Care System (Sweden). Int J Cancer 2009;124:180–7.

- Dalton SO, Steding-Jessen M, Engholm G, et al. Social inequality and incidence of and survival from lung cancer in a population-based study in Denmark, 1994-2003. Eur J Cancer 2008;44:1989–95.

- Ekberg-Aronsson M, Nilsson PM, Nilsson JA, et al. Socio-economic status and lung cancer risk including histologic subtyping-a longitudinal study. Lung Cancer 2006;51:21–9.

- Margolis ML, Christie JD, Silvestri GA, et al. Racial differences pertaining to a belief about lung cancer surgery: results of a multicenter survey. Ann Intern Med 2003;139:558–63.

- Lathan CS, Neville BA, Earle CC. The effect of race on invasive staging and surgery in non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:413–18.

- Gordon HS, Street RL, Jr., Sharf BF, et al. Racial differences in doctors’ information-giving and patients’ participation. Cancer 2006;107:1313–20.

- Berglund A, Holmberg L, Tishelman C, et al. Social inequalities in non-small cell lung cancer management and survival: a population-based study in central Sweden. Thorax 2010;65:327–33.

- Sidorchuk A, Agardh EE, Aremu O, et al. Socioeconomic differences in lung cancer incidence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Causes Control 2009;20:459–71.

- Forrest LF, Adams J, Wareham H, et al. Socioeconomic inequalities in lung cancer treatment: systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med 2013;10:e1001376.

- Dalton SO, Steding-Jessen M, Jakobsen E, et al. Socioeconomic position and survival after lung cancer: influence of stage, treatment and comorbidity among Danish patients with lung cancer diagnosed in 2004–2010. Acta Oncologica 2015;54:797–804.

- Dalton SO, Johansen C. New paradigms in planning cancer rehabilitation and survivorship. Acta Oncol 2013;52:191–4.

- Mountain CF. Revisions in the international system for staging lung cancer. Chest 1997;111:1710–17.

- Travis WD, Colly TV, Corrin B. Histological typing of tumours of lung and pleura. In: Sobin LH, editor. World Health Organization international classification of tumours. 3rd ed. Berlin, Germany: Springer, 1999.

- Tomson Y, Aberg H. Risk factors for cardiovascular disease-a comparison between Swedes and immigrants. Scand J Prim Health Care 1994;12:147–54.

- Hemminki K, Li X, Czene K. Cancer risks in first-generation immigrants to Sweden. Int J Cancer 2002;99:218–28.

- Hjern A. High Use of Sedatives and Hypnotics in Ethnic Minorities in Sweden. Ethn Health 2001;6:5–11.

- Hjörleifsdottir Steiner K, Johansson S-E, Sundquist J, et al. Self-Reported Anxiety, Sleeping Problems and Pain Among Turkish-Born Immigrants in Sweden. Ethnicity and Health 2007;12:363–79.

- Hjern A, Grindef JM. Dental Health and Access to Dental Care for Ethnic Minorities in Sweden. Ethn Health 2000;5:23–32.

- Gadd M, Johansson SE, Sundquist J, et al. Morbidity in cardiovascular diseases in immigrants in Sweden. J Intern Med 2003;254:236–43.

- Lindstrom M, Sundquist J. Ethnic differences in daily smoking in Malmö, Sweden. Varying influence of psychosocial and economic factors. Eur J Public Health 2002;12:287–94.