Abstract

Background: Self-rated health (SRH) has been shown to be a strong predictor of mortality from a number of major chronic diseases, however, the association with cancer remains unclear. The aim of this study was to investigate a possible association between change in SRH and cancer incidence.

Materials and methods: SRH and information on lifestyle and other risk factors were obtained for 13–636 women in the Danish Nurse Cohort. Cancers that developed during 12 years of follow-up were identified in the National Patient Registry. An association between SRH and cancer was examined in a Cox proportional hazards model with adjustment for age, smoking, alcohol, marital status, physical activity, body mass index and estrogen replacement therapy.

Results: No significant association was found between SRH and overall cancer incidence in the age-adjusted Cox proportional hazards model (1.04; 95% CI 0.93–1.16), even after adjustment for potential confounding factors (HR 1.08; 95% CI 0.96–1.21). Likewise, there was no significant association between SRH and breast cancer (HR 1.09; 95% CI 0.89–1.33), lung cancer (HR 1.03; 95% CI 0.71–1.49) or colon cancer (HR 1.08; 95% CI 0.75–1.54).

Conclusion: SRH is not significantly associated with the incidence of all cancers or breast, lung or colon cancer among Danish female nurses. Women who reported a decrease in SRH between 1993 and 1999 had the same risk for cancer as those who reported unchanged or improved SRH.

The question of whether social and psychological factors contribute to the development of cancer has attracted attention for decades. Although genetic, environmental, lifestyle and socioeconomic factors have been identified as risk factors for cancer, the contribution of psychological factors has been questioned [Citation1]. A review in 2008 suggested that psychological distress, including depression, anxiety and poor quality of life, lead to considerable increases in both the incidence of and mortality from cancer [Citation2], however, that review has been criticized on the grounds of the poor quality of the studies included and due to methodological and statistical issues [Citation3]. Furthermore, a review in 2004 of studies conducted over the previous 30 years on the significance of psychological factors in the development of cancer found no association [Citation4]. The overall evidence from prospective studies with unbiased information on exposure and outcome also does not support an association, leaving little likelihood of an association [Citation5].

Self-rated health (SRH) is used increasingly as a measure in epidemiological research. This measure reflects various aspects and people’s health in general [Citation6]. Culture, age, gender as well as biological, psychological and social dimensions are all included when health is rated by the individual [Citation7]. SRH has proven to be a strong independent predictor of mortality, disease-specific mortality and the incidence of a number of chronic diseases such as diabetes and cardiovascular diseases [Citation6].

To our knowledge, there are only four published studies on the association between SRH and cancer risk (morbidity), and none found an association with poor SRH. A Norwegian cohort study (2013) comprised 25 532 participants and 10 years of follow-up, but no data were reported on participants aged 48–69 years or on marital status, which is an important factor in the development of cancer [Citation8]. In a Dutch study (1993) of 783 men, only 60 cases of cancer were diagnosed during follow-up, which limits the weight of the evidence from this study. Furthermore, there was no adjustment for physical activity, which is an important risk factor for cancer [Citation9]. In a longitudinal study in the USA (2012), with 4770 participants, recall bias and misclassification of the outcome may have been present due to self-reported onset of cancer. Furthermore, there may have been confounding factors from alcohol consumption, as no information on this factor was available [Citation10]. In a Danish cohort study with 4493 participants and only 102 cancer cases diagnosed during follow-up, separate analyses were not performed for different cancer sites and there were no data on body mass index, which has also been shown to play an important role in the development of cancer [Citation11]. In all these studies, only one measure was made of SRH, at baseline, and therefore changes over time could not be measured.

The aim of this study was to investigate the association between change in SRH and risks for all cancers and for breast, lung and malignant neoplasms of digestive organs, the most common types of cancer among Danish women: we also addressed some of the limitations of previous studies, such as repeated measurement of SRH.

Materials and methods

Study population and data material

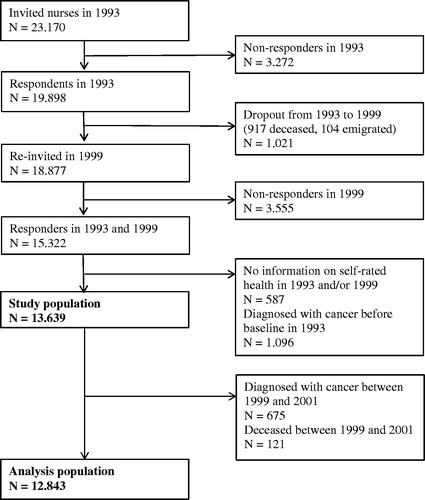

The data for our study were derived from the Danish Nurse Cohort established in 1993 to study the effect of hormone replacement therapy on osteoporosis. All female members of the Danish Nurses’ Organization over the age of 44 (N = 23 170) were recruited for the study, and 19 898 (86%) completed a questionnaire. In 1999, a second questionnaire was posted to the same nurses and also to nurses who had attained 45 years of age since the first questionnaire in 1993. A total of 15 322 nurses (76%) completed the second questionnaire [Citation12]. Nurses with a diagnosis of cancer at baseline (N = 1096) and nurses for whom information on SRH in 1993 and/or in 1999 (N = 583) was missing were excluded from this study (). Thus, the study population for the descriptive analysis consisted of the remaining 13 639 women. A lag between 1999 and 2001 was introduced to minimize the effect of reverse causality, and an additional 796 women died or developed cancer during this period. The study population for the regression analysis consisted of 12 843 women.

The study protocol was declared to the Data Protection Authority and approved by the Regional Ethics Committee [Citation2].

The questionnaire

SRH was measured from answers to a standard question used in several previous studies [Citation13]: “How would you rate your current state of health in general?” with five possible answer categories: “very good”, “good”, “fair”, “poor” and “very poor”. The question has been validated and has shown high reliability [Citation3,Citation4]. In this study, the categories “very good” and “good” were combined to form the category “good SRH”; “fair” remained; and “poor” and “very poor” were combined to form the category “poor SRH”.

Information on a number of demographic variables and lifestyle factors was self-reported and collected at baseline. The variables were age, marital status, number of children, menopausal status, physical leisure activity, smoking history, alcohol consumption and body mass index (kg/m2).

Outcome

The primary outcome was incidence of cancer. The study population was followed from January 2001 to the date of the first registration of cancer, death, emigration or the end of follow-up (October 2013), whichever occurred first. Thus, the maximum follow-up was 12 years. Cancer diagnoses were obtained from the National Patient Registry, which has registered all hospital admissions in Denmark since 1976 through personal identification number [Citation14] and codes them according to the International Classification of Diseases (ICD). The cancer diagnoses in this study were covered by ICD-10 codes C00-C97, with the exclusion of non-melanoma skin cancer. The date of death was obtained from the Danish Causes of Death Register [Citation15].

Statistical analysis

The predictive value of decreased SRH over time on the risk for development of cancer was estimated as hazard ratios (HRs) by application of the Cox proportional hazards model. We adjusted the risk estimates for the potential confounding factors marital status, physical leisure activity, smoking history and alcohol consumption, body mass index and estrogen replacement therapy. To estimate the effect of a negative change in SRH over time, women who had unchanged or improved SRH were used as the reference group. A two-year lag between 1999, when the last survey was completed, and 2001, the start of follow-up of cancer, was used to minimize reverse causality. Respondents for whom data were missing were omitted from the analysis. We performed separate analyses for the three most frequent types of cancer in Danish women: breast (C-50), lung (lung, bronchus and trachea; C 30-39) and malignant neoplasms of digestive organs (C 15-26). All statistical analyses were performed with the statistical software package SAS version 9.3.

Results

Characteristics of the study population

The 1840 cancer cases identified in this population included 589 cases of primary breast cancer, 159 cases of lung cancer and 243 cases of malignant neoplasms of digestive organs (). Good SRH was reported at baseline by 84% of the study population, fair SRH by close to 14% and poor SRH by almost 2%. The mean age was 55 years (SD 7.8) (). Women who reported poor SRH were more likely to be older, widows, previous users of hormone replacement therapy and unmarried or divorced than those who reported good SRH. Those with poor SRH were also more often smokers, more often had an alcohol consumption of 1–4 units per week, were less physically active and more often had a body mass index >18.5 kg/m2 and >30 kg/m2 ().

Table 1. Sites of cancers in the study population from 2001 to 2013. The Danish Nurse Cohort. N = 12 843.

Table 2. Demographic and lifestyle characteristics of the study population according to self-rated health. The Danish Nurse Cohort. N = 13 639.

Changes in SRH between 1993 and 1999

Of the 13 639 participants, 7993 women (59%) had unchanged SRH between 1993 and 1999, 3245 (24%) reported a decrease, and 2401 (18%) reported improved SRH.

Association between SRH and cancer incidence

Based on the baseline SRH measure in 1993 a total of 2515 participants had a cancer diagnosis in the study period (results not shown). Among those with a very good or good SRH 2102 got a cancer diagnosis. Among those with an average SRH 379 had a cancer diagnosis, and among those with a poor or very poor SRH 43 had equivalent. In an age-adjusted Cox proportional hazard regression model, participants with decreased SRH over time had the same risk for cancer as those with unchanged or increased SRH (HR 1.05; 95% CI 0.94–1.17) (). Multivariate adjusted analysis did not change this result (HR 1.08; 95% CI 0.96–1.21) ().

Table 3. Hazard ratios for overall cancer, breast, lung and colon cancer according to self-rated health. The Danish Nurse Cohort. N = 12 843.

Further analyses were performed on the three most frequent cancer types among Danish women. No significant associations with SRH were observed (breast cancer, HR 1.09; 95% CI 0.89–1.33; lung cancer, HR 1.03; 95% CI 0.71–1.49 and malignant neoplasms of digestive organs, HR 1.08; 95% CI 0.75–1.54; ).

Discussion

The women in this study had a 10% higher prevalence of good or very good SRH than women in the general Danish population, even after taking into account the social class of nurses [Citation16].

One fourth of the participants reported decreased SRH during the period 1993–1999, while almost one fifth reported an increase. Decreased SRH may be related to physical disability and the medical problems that come naturally with age [Citation17]. More than half the participants in this study had unchanged SRH between 1993 and 1999, which may indicate either that SRH is a stable health measure or that a persistent attitude to life rarely changes over time. In a study in 1992, changes in SRH rated eight times during 3 years were investigated among 251 Americans over the age of 62 [19]. Although the sample size was small, the results are in agreement with ours, showing that SRH is generally stable [Citation18].

Our main finding, that the perception of health in general over time is a risk factor for cancer later in life, is in line with the findings of a similar prospective cohort study of 25 532 participants [Citation8]. In contrast to that large cohort study, we did not find an increased risk for lung cancer among people with poor SRH. This discrepancy might be because of a heterogenic and older study population in the cohort study by Riise et al. [Citation8] and the selected, younger, and more homogenous study population in this study.

Our results are supported by the findings of three prospective cohort studies of the association between SRH and the incidence of chronic diseases including cancer [Citation10,Citation11], although these studies had medium to small samples (N = 4493, 4770, 783, respectively) and few cancer cases (N = 102, 544, 60, respectively), making site-specific cancer risk analysis difficult. In our study we had a larger study population and a larger number of cancer cases than any of the previous mentioned studies. Furthermore, SRH was measured at only one time. Therefore, they cannot demonstrate an association between changes in SRH over time and the risk for cancer.

As previous studies suggested that poor SRH may reflect subclinical disease and underlying biological and psychological changes [Citation6,Citation9], we introduced a two-year time lag in follow-up for cancer between 1999 and 2001 to avoid potential reverse causation. This changed our results in the direction of a null finding.

Factors, such as subjective somatic perception, identity and personality traits, have been found important for evaluating perceptions of health [Citation19]. Poor SRH has been associated with stress, depression, negative life events and personality traits, such as tension and anger. The same personality traits are associated with people with a type A personality, who have a higher risk for and mortality from cardiovascular disease [Citation20], however, there is no substantial evidence that stress, depression, negative life events and personality traits are risk factors for cancer. In several prospective studies, no association was found between stress or depression and the subsequent risk for cancer [Citation5,Citation21]. Similar findings were made in a review in 2004 of literature in the previous 30 years on the significance of psychological factors for cancer risk [Citation4]. A meta-analysis in 2008 found the opposite result: an association between various psychological factors and the risk for cancer [Citation2]. This meta-analysis has, however, been criticized because it included studies with short follow-up, few cancer cases, insufficient statistical strength and insufficient adjustment for confounding factors [Citation3].

Strengths and limitations

Strengths

This study is based on a comprehensive, thorough epidemiological survey of a homogeneous population with the same education and gender. The exposure variable was measured twice, which made it possible to determine whether a decrease in SRH over time is a risk factor for cancer later in life. This has not previously been examined.

The strong points of this study are its prospective design, the high participation rate (86% in 1993 and 77% in 1999), the large number of cancer cases and no loss to follow-up, as access to the Danish National Patient Registry secured complete follow-up for the outcome under study. The prospective register-based design minimized selection and information bias, and the 12-year follow-up made it possible to investigate SRH as a risk factor for cancer over a relatively long period. The time between initiation and detection of breast, lung and malignant neoplasms of digestive organs has, however, been estimated to be up to one or two decades [Citation22], which might explain the observed significant association between a decrease in SRH over time and overall cancer incidence before introduction of the two-year lag in the analysis (data not shown). We cannot rule out that early symptoms of undiagnosed cancer had a negative effect on SRH for some participants.

As in all observational studies, there may have been residual confounding factors. We had no appropriate information on diet, which plays an important role in SRH and the development of cancer [Citation23]. In addition, we did not adjust for chronic disease at baseline, as this would have created an artificial disease-free study population. Nevertheless, certain chronic diseases, e.g. diabetes, have been identified as risk factors for colon cancer [Citation24].

As the SRH of only two participants in the study changed from poor to very poor and that of only 155 from fair to poor, use only of participants with SRH that changed from poor to very poor as our exposure group would not have been statistically sound. It is possible that the results for an association between a decrease in SRH over time and cancer incidence would have been different if this had been the case. The fact that the exposure group included all participants who experienced a decrease in SRH over time might have resulted in underestimation of the risk.

Conclusion

In this large cohort study with repeated measures of SRH, we observed no increase in the risk for cancer overall among women with poor SRH. In addition, we did not find increased risks for cancers of the breast, colorectal or lung. These results do not indicate that SRH plays a role in cancer causation.

Disclosure statement

None to declare.

References

- Colditz GA, Sellers TA, Trapido E. Epidemiology: identifying the causes and preventability of cancer? Nat Rev Cancer 2006;6:75–83.

- Chida Y, Hamer M, Wardle J, et al. Do stress-related psychosocial factors contribute to cancer incidence and survival? Nat Clin Pract Oncol 2008;5:466–75.

- Coyne JC, Ranchor AV, Palmer SC. Meta-analysis of stress-related factors in cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2010;7. doi: 10.1038/ncponc1134-c1.

- Garssen B. Psychological factors and cancer development: evidence after 30 years of research. Clin Psychol Rev 2004;24:315–38.

- Dalton SO, Boesen EH, Ross L, et al. Mind and cancer. do psychological factors cause cancer? Eur J Cancer 2002;38:1313–23.

- Idler EL, Benyamini Y. Self-rated health and mortality: a review of twenty-seven community studies. J Health Soc Behav 1997;38:21–37.

- Manderbacka K. Examining what self-rated health question is understood to mean by respondents. Scand J Soc Med 1998;26:145–53.

- Riise HKR, Riise T, Natvig GK, et al. Poor self-rated health associated with an increased risk of subsequent development of lung cancer. Qual Life Res Int J Qual Life Asp Treat Care Rehabil 2014;23:145–53.

- Pijls LT, Feskens EJ, Kromhout D. Self-rated health, mortality, and chronic diseases in elderly men. The Zutphen Study, 1985-1990. Am J Epidemiol 1993;138:840–8.

- Latham K, Peek CW. Self-rated health and morbidity onset among late midlife U.S. adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2013;68:107–16.

- Flensborg-Madsen T, Johansen C, Grønbæk M, et al. A prospective association between quality of life and risk for cancer. Eur J Cancer Oxf Engl 1990 2011;47:2446–52.

- Hundrup YA, Simonsen MK, Jørgensen T, et al. Cohort profile: the Danish nurse cohort. Int J Epidemiol 2012;41:1241–7.

- Lundberg O, Manderbacka K. Assessing reliability of a measure of self-rated health. Scand J Soc Med 1996;24:218–24.

- Jürgensen HJ, Frølund C, Gustafsen J, et al. Registration of diagnoses in the Danish National Registry of Patients. Methods Inf Med 1986;25:158–64.

- Juel K, Helweg-Larsen K. The Danish registers of causes of death. Dan Med Bull 1999;46:354–7.

- Ekholm Ola KM, Davidsen Michael H. ulrik. Sundhed og sygelighed i Danmark 2005 & udvikling siden 1987. Statens Institut for Folkesundhed; 2006.

- Niels Kristian Rasmussen. Sundhed og sygelighed i Danmark 1987. DIKEs undersøgelse, København; 1988.

- Rodin J, McAvay G. Determinants of change in perceived health in a longitudinal study of older adults. J Gerontol 1992;47:P373–84.

- Mora PA, DiBonaventura MD, Idler E, et al. Psychological factors influencing self-assessments of health: toward an understanding of the mechanisms underlying how people rate their own health. Ann Behav Med Publ Soc Behav Med 2008;36:292–303.

- Nabi H, Kivimäki M, Zins M, et al. Does personality predict mortality? Results from the GAZEL French prospective cohort study. Int J Epidemiol 2008;37:386–96.

- Lemogne C, Consoli SM, Melchior M, et al. Depression and the risk of cancer: a 15-year follow-up study of the GAZEL cohort. Am J Epidemiol 2013;178:1712–20.

- Friberg S, Mattson S. On the growth rates of human malignant tumors: implications for medical decision making. J Surg Oncol 1997;65:284–97.

- Osler M, Heitmann BL, Høidrup S, et al. Food intake patterns, self rated health and mortality in Danish men and women. A prospective observational study. J Epidemiol Community Health 2001;55:399–403.

- Yuhara H, Steinmaus C, Cohen SE, et al. Is diabetes mellitus an independent risk factor for colon cancer and rectal cancer? Am J Gastroenterol 2011;106:1911–21. quiz 1922.