Abstract

Background: Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death worldwide. The incidence and mortality rate of lung cancer in women has increased. Studies have indicated that females with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) have better survival than males. We aimed to examine the impact of gender on 1-, 5- and 10-year survival after surgery for stage I and II NSCLC.

Materials and methods: During the period 2003–2013, 692 patients operated for stage I and II NSCLC were prospectively registered. Patients were stratified into four groups according to gender and age over or less than 66 years. The relationship between gender and age on overall survival was investigated. Adjustment for multiple confounders was performed using the Cox proportional hazard regression model.

Results: Surgical resection was performed in 368 (53.2%) males and 324 (46.8%) females. During the study period, mortality was 35.2% in younger females, 34.9% in younger males, 42.8% in older females and 51.2% in older males. Stratified by age, there were no significant gender differences with regard to survival [hazard ratio (HR) 1.16, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.91–1.46, p = .23]. Comparing the younger and the older patients adjusted for confounders, the mortality risk was significantly increased in elderly patients [females, adjusted HR 1.60, 95% CI 1.12–2.28]. Compared with population data, standardized mortality ratio was increased to 4.1 (95% CI 3.5–4.7) in males and to 6.5 (95% CI 5.4–7.6) in females.

Conclusion: Overall survival did not differ significantly between males and females. Adjusted for confounding factors, we found a significantly increased mortality risk in elder patients compared to their younger counterparts. However, five-year overall survival of more than 50% for older patients with NSCLC should encourage surgical treatment also in elderly lung cancer patients.

Introduction

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death worldwide. In 2014, 2158 patients died of lung cancer in Norway (1198 men and 960 women) and in the same year, 3019 new cases were diagnosed [Citation1]. In the five-year period 2010–2014, the age-standardized incidence rates of lung cancer in Norway were, respectively, 50.4 per 100 000 person-years in females and 71.4 in males [Citation1]. This represented an increase from 37.5 in females and a slight decrease from 72.3 in males, compared to the period 2000–2004. Over 60 years, the incidence of lung cancer in women has increased almost 10-fold [Citation1], and has become an issue of major concern. The recommended, and best documented treatment for early stage lung cancer, is surgical resection [Citation2], and approximately 25% of all operations for primary lung cancer in Norway are performed in our tertiary university center.

Multiple studies have indicated that females with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) have better survival prognosis than males [Citation3–5]. Gender-associated differences in clinical characteristics such as histological tumor type, smoking habits, type and rate of surgical resection, and number and type of risk factors have been reported [Citation4,Citation6–12].

Several of the studies reporting better survival in females, featured inconsistent staging and spanned time periods during which the treatment algorithms changed [Citation6,Citation7,Citation12]. Some studies were large registry studies where data are complicated by biases of reporting and lack of sufficient detail [Citation4,Citation10,Citation11]. Other studies are old, reporting data collected before and shortly after the turn of the century [Citation9–11] In a meta-analysis,[Citation5], similar survival between female and male patients was reported in some studies [Citation13–19]. However, most of those studies included relatively few patients (n = 90–200) [Citation13–15,Citation17], and the proportions of females were low (10–27%) [Citation16,Citation18,Citation20]. Other studies had a retrospective design [Citation15,Citation18,Citation20], and included patients with all tumor stages and various treatment modalities [Citation19,Citation20]. In general, most of the studies were not primarily designed to analyze differences in survival between female and male patients.

In summary: although studies on gender-related differences in survival after surgery for NSCLC have shown conflicting results, the prevailing opinion is that the prognosis is better for females than for males. We have consecutively collected detailed demographic information as well as information on major risk factors expressed through the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI), smoking habits and lung function measurements. This has given us the opportunity to study adjustable gender-related differences in survival after surgery for early stage NSCLC. In the present study, we aimed to examine the impact of gender on 1-, 5- and 10-year survival after surgery for stage I and II lung cancer.

Methods

Patients

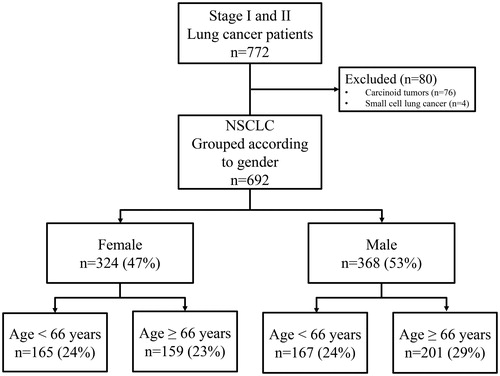

During a 10-year period (2003–2013), 692 patients with histologically confirmed NSCLC [adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, large cell carcinoma and carcinoma, not otherwise specified (carcinoma, NOS)] according to guidelines were registered in the hospital’s lung cancer database [Citation21]. Patients with small cell lung cancer and carcinoid tumors were excluded from the study (). Demographic characteristics of the patients are shown in and .

Figure 1. Surgically treated stage I and II lung cancer patients. NSCLC: non-small cell lung cancer.

Table 1(a). Characteristics of 692 patients surgically treated for NSCLC according to gender and age.

The National Registry of Norway provided data on birth and death dates. Clinical data were collected at admission and from the patients’ hospital charts. All patients completed a self-administered questionnaire on smoking habits, current medication and former diseases. No data on disease recurrence or specific causes of death were registered.

Patients were referred to our tertiary university center from their local hospitals in the southern parts of Norway (population approximately 1.2 million). Prior to referral, all patients underwent primary assessment according to national and international guidelines [Citation2,Citation22]. About one week postsurgery, after removing chest tubes and controlling pain and possible infections, all patients were transferred back to their respective hospitals. Systematic dissection or lymph node sampling was performed according to international guidelines [Citation2]. In line with internal hospital routines, all patients were treated with pre- and postoperative prophylactic antibiotics. The study was approved by the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics. Written consent was obtained from all patients.

Tumor classification

All tumors were classified according to the seventh TNM classification. Patients entered in the registry before the introduction of the seventh edition were manually reassessed to be comparable. To ensure a correct pathological TNM staging, the surgically obtained tissue specimens were used to describe tumor distribution at time of surgery.

Comorbidities and confounders

Comorbidities were classified according to the CCI (counting numbers of cardiovascular, endocrine or other present comorbidities at time of surgery) and dichotomized. The Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status (ECOG PS) to assess the preoperative status, was categorized as ECOG PS ≤1 or ECOG PS >1. Other aggregated variables were data on body mass index (BMI), pack-years of smoking, lung function [forced vital capacity (FVC), forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1), the ratio FEV1/FVC, and the diffusing capacity of lung for carbon monoxide (DLCO)] and postoperative days in need of thoracic drainage. Airflow limitation was determined according to The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD).

Statistical analyses

Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement guidelines were used to report our cohort study. The dynamic cohort of patients was followed from the date of surgery until death or end of follow-up. Follow-up data were censored with closing date 10 October 2014. To equalize the possible bias of age, we used the mean age of 66 years for both female and male patients to age stratify into four groups, male and female, aged over or under 66 years of age. All other variables were of interest only as possible confounders of the association between gender stratified by age and overall survival.

All potentially confounding variables were identified using bivariate analysis and significant variables were included in the multiple regression model. Adjustment for multiple confounders was performed using the Cox proportional hazard regression model with a manual backward stepwise elimination procedure. The effects were quantified by hazard ratios (HRs) with its 95% confidence interval (CI).

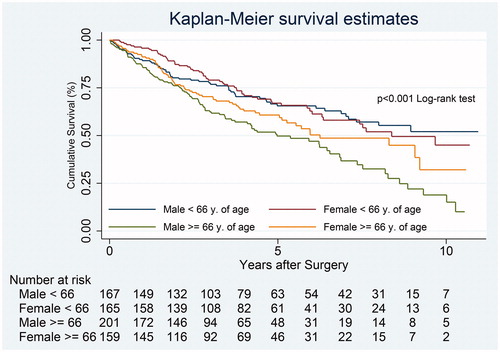

Survival curves were constructed with the Kaplan-Meier method to determine differences between female and male patients, younger and older than mean age. Differences were estimated by the Breslow and log-rank test statistics. Differences in continuous variables between the groups were estimated by one-way analysis of variances (ANOVA) or independent sample t-test, as appropriate. The χ2-test for contingency tables with different degrees of freedom was used to detect associations between categorical independent variables. All p-values were two-sided, and a p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The observed mortality in our cohort of NSCLC patients was compared to the expected total mortality of the Norwegian population stratified on age and gender. This permitted estimation of a standardized mortality ratio (SMR) with 95% confidence interval limits. Statistical analyses were performed using STATA version 13 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX), IBM SPSS Statistics version 22 (IBM SPSS, Chicago, IL) and OpenEpi (Open Source Epidemiologic Statistics for Public Health).

Results

Characteristics

The study population (n = 692) comprised 368 (53.2%) males and 324 (46.8%) females. The population characteristics are shown in and .

The patterns of smoking were similar between younger males and females. The highest number of pack-years (36.0 years) was found in younger males. There were more never-smokers among older females (17.0%) than in the other groups. The CCI showed an overweight of comorbidities among older males (38.9%). Lobectomy was the most common surgical procedure in older patients (females 79.9% and males 71.6%) and pneumonectomy was more frequently performed in younger patients (females 12.6% and males 20.4%) than in the older. Adenocarcinoma was the most frequent histological type in females (64.8%) and there were more squamous cell carcinomas in males (younger males 34.7% and older males 38.3%) than in females.

Survival and mortality

During the median follow-up time of 3.5 years (range 4 days–11.7 years), 288 patients (41.5%) died. Females had nearly 10% increased overall survival compared to males, but the difference did not reach statistical significance (). During the study period, mortality was 35.2% in younger females, 34.9% in younger males, 42.8% in older females and 51.2% in older males. The median cumulative survival of all patients was seven years. During the first five years, cumulative survival did not differ significantly between the four age and gender groups (). Ten years after surgery there was an almost 10%, increased survival (p = .03) in older females (28.2%) compared to older males (19.5%), (). However, at the end of follow-up the difference was no longer statistically significant (p = .06).

Figure 2. Overall survival after surgical intervention for non-small cell lung cancer according to gender and age.

Table 2. Overall 1-, 5- and 10-years cumulative survival after surgical resection for NSCLC in 692 patients according to gender. [AQ2]

Table 3. Overall 1-, 5- and 10-years cumulative survival after surgical resection for NSCLC in female and male patients over and under 66 years of age.

Crude mortality

Stratifying the cohort according to female and male gender, we found no statistically significant difference in mortality (HR 1.21, 95% CI 0.96–1.53, p = .10) (). There was a borderline increased mortality risk in older females compared to younger females (HR 1.42, 95% CI 1.00–2.01, p = .052). When comparing younger and older males, there was a significant difference in crude mortality in favor of the younger patients (HR 1.90, 95% CI 1.37–2.62, p < .001).

Table 4. Association of overall mortality between the genders and the genders stratified by age. Crude and adjusted for multi-confounding (Cox proportional hazard regression) in a cohort of 692 resected NSCLC patients.

Table 1(b). Surgical and histological characteristics of 692 patients resected for NSCLC according to gender and age.

Adjusted mortality

There was no significant difference in mortality between the genders (HR 1.16, 95% CI 0.91–1.46, p = .23) (). Applying Cox proportional hazard regression model, including tumor stage and lobectomy as covariates (i.e. confounders), no significant gender difference was found.

Tumor stage, lobectomy and large cell carcinoma were identified as confounders when analyzing gender and age groups. Controlling for multi-confounding, there was no difference in overall survival between males and females within the same age groups. Comparing the younger and the older patients adjusted for confounders, the mortality risk was significantly increased in elderly females (HRadj. 1.60, 95% CI 1.12–2.28, p = .01) compared to the younger females.

Comparing survival with the Norwegian population

Based on national data, the expected number of deaths in the male population was 39.4. In comparison, there were 162 observed deaths in male patients. This results in a SMR in our male patient cohort of 4.1 (95% CI 3.5–4.7, p < .001), as compared with the risk of mortality in the total male Norwegian population controlling for age distribution. There were 126 observed deaths in female patients and the expected number was 19.4. The SMR in our female cohort was 6.5 (95% CI 5.4–7.6, p < .001).

Discussion

Principal findings

In the present study, the overall survival rates did not differ significantly between male and female patients with stage I and II NSCLC, when compared to their respective peers. This is in contrast to multiple other studies which have reported increased survival in females compared to males [Citation5,Citation7,Citation11,Citation23], but in line with the anticipated diminishing gap in gender differences suggested by others [Citation24]. We found that the difference in overall survival between the youngest and the oldest patients was not present until more than five years after surgery. However, there were no survival differences between the genders within the respective age groups. Adjusted for confounding factors, we found a significantly increased mortality risk for the older patients as compared to the younger patients. This indicates that increased age per se is a risk factor for death.

Smoking patterns

One possible explanation for finding similar survival between male and female patients may be that gender differences in cigarette smoking have diminished [Citation25]. In the present study the patterns of smoking had a similar distribution of never-, ex- and current smokers in younger male and female patients. Among the older female patients, there were significantly more never-smokers compared to the other three age and gender groups. The similarity in cigarette smoking among the younger patients is comparable to the findings of Jemal et al [Citation25]. They also found that lung cancer mortality rates have converged between younger men and women, which they imply could be due to similar patterns of smoking between the genders. Although the patterns of smoking were similar between the genders in the present study, the number of pack-years was significantly higher in males. Pack-years were therefore included in the multivariate analysis, but did not affect mortality risk which remained similar between the genders, indicating that smoking per se is more important than the amount smoked.

Crude HR between older males and females was borderline significant (p = .06), and showed 35% increased mortality risk in older males compared to older females. However, when controlled for confounding factors, the difference was not significant (p = .25). In other studies that have included fewer females [Citation8,Citation20,Citation23], the differences in smoking patterns between the genders have been more pronounced than in the present study.

Data collection and histology

In the registry studies by Wisnivesky et al. and Ou et al. [Citation10,Citation11], data were collected during the periods 1991–1999 and 1989–2003, respectively. Being large registry studies, both lacked accurate information on risk factors like smoking and lung function. Also, Wisnivesky included only patients aged 65 and above due to limitations in the two registries that constituted the basis of the study. Our data collection was performed from 2003 until 2013 and we compared gender differences in both older and younger patients. Wisnivesky et al. suggested that lung cancer in elderly females may have a different natural history and tumor biology than that in males. This speculation was based on the finding that better survival in women was associated with higher proportions of adeno- and large cell carcinoma. Also in our cohort, the distribution of both adeno- and large cell carcinoma was higher in females than in males, but only large cell carcinoma affected the multivariate analyses. Despite an even higher proportion of adenocarcinoma and a similar proportion of large cell carcinoma in our study, we did not find better survival in females than in males.

Age and comorbidities

The prognoses for resected NSCLC, expressed in terms of five-year survival rates, are accepted to be better for stage I than stage II tumors [Citation2]. Ou et al. found 20% reduced mortality risk in women compared to men with stage Ia and Ib NSCLC. Similarly, we found a reduced crude mortality rate of 26% in women. Despite the dominance of stage I (79.3%) among the age-comparable older females in our study, the gender difference in mortality rate disappeared after controlling for significant confounding factors such as histology, smoking, stage and surgical approach. The study by Ou et al. did not adjust for risk factors like comorbidities and smoking.

A Norwegian study by Båtevik et al. found that female gender had a positive effect on survival [Citation23]. However, in that study the distribution of female and male patients was 1:2 and the study comprised only 351 patients over a 15-year period (1988–2003). Further, the study had a retrospective design and included also stages I-III. They did not control for lung function and other risk factors except cardiovascular disease, which was described as borderline significant in the multivariate Cox analyses. In our study, comorbidities, including cardiovascular disease and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in general, did not affect overall survival, despite a higher rate of comorbidities among the male patients.

Also another population-based Norwegian study reported survival benefit in females [Citation4]. The study included all histological subtypes and did not adjust for different treatment modalities, comorbidities and risk factors like smoking. Even in patients with localized disease, survival in females was better than in males. However, the increase in overall five-year cumulative survival in the period 2003–2007, compared with the period 1998–2002, was most noticeable in males, increasing from 31.8% to 40.9% in males and only from 49.9% to 51.8% in females over the same periods. This may indicate that the female advantage in survival after treatment of lung cancer is diminishing.

According to international guidelines, surgical resection is the treatment of choice in early stage lung cancer patients [Citation2,Citation22]. However, due to comorbidities some patients are not fit for surgery. Hence, there are patients treated by chemotherapy or radiation with curative intent who are not included in our study. Whether this affects the overall survival in a gender-specific way is not known. Unfortunately, our database contains no information on patients rejected for surgical resection.

Life expectancy

In the previously mentioned study by Båtevik et al., females had better survival after adjusting for the effects of life expectancy [Citation23]. This is in contrast to our study where mortality, compared with population data, was 4.1 times higher than expected in the male cohort. Mortality in the female cohort was 6.5 times higher compared with population data, and both female and male differences were statistically significant. Although this is worrying, it may partly be explained by the supplementary risk of various comorbidities in lung cancer patients. It is likely that lung cancer patients may carry an overall higher risk of death also from causes other than lung cancer, compared to the general population.

Conclusion

In a cohort of surgically treated stage I and II NSCLC patients we could not show any survival difference between male and female patients. This is in contrast to several older studies, but in line with the anticipated diminishing gap in gender differences suggested by others. The higher SMR in female patients is of concern. However, lung cancer patients are known to have more comorbidities and risk factors for mortality than the general population. As expected, when adjusted for smoking, lung function, type of surgery and tumor type, there was an increased mortality risk in older patients. In spite of this, a five-year overall survival of more than 50% in older patients with NSCLC may encourage surgical treatment also in elderly lung cancer patients.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this article.

Funding

This work did not involve any external financial support.

References

- Norway Cro [Internet]. Cancer in Norway 2014: Cancer incidence, mortality, survival and prevalence in Norway. 2015 [cited 2016 Mar 29]. Available from: https://www.kreftregisteret.no/globalassets/cancer-in-norway/2014/cin_2014.pdf.

- Howington JA, Blum MG, Chang AC, et al. Treatment of stage I and II non-small cell lung cancer: Diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2013;143(5 Suppl):e278S–e313S.

- Graham PD, Thigpen SC, Geraci SA. Lung cancer in women. South Med J. 2013;106:582–587.

- Sagerup CM, Smastuen M, Johannesen TB, et al. Sex-specific trends in lung cancer incidence and survival: a population study of 40,118 cases. Thorax. 2011;66:301–307.

- Nakamura H, Ando K, Shinmyo T, et al. Female gender is an independent prognostic factor in non-small-cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis. Ann Thoracic Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;17:469–480.

- Cerfolio RJ, Bryant AS, Scott E, et al. Women with pathologic stage I, II, and III non-small cell lung cancer have better survival than men. Chest. 2006;130:1796–1802.

- Visbal AL, Williams BA, Nichols FC, 3rd., et al. Gender differences in non-small-cell lung cancer survival: an analysis of 4,618 patients diagnosed between 1997 and 2002. Ann Thoracic Surg. 2004;78:209–215.

- Alexiou C, Onyeaka CV, Beggs D, et al. Do women live longer following lung resection for carcinoma? Eur J Cardio-Thoracic Surg. 2002;21:319–325.

- Koike T, Tsuchiya R, Goya T, et al. Prognostic factors in 3315 completely resected cases of clinical stage I non-small cell lung cancer in Japan. J Thoracic Oncol. 2007;2:408–413.

- Ou SH, Zell JA, Ziogas A, et al. Prognostic factors for survival of stage I nonsmall cell lung cancer patients: a population-based analysis of 19,702 stage I patients in the California. Cancer Registry from 1989 to 2003. Cancer. 2007;110:1532–1541.

- Wisnivesky JP, Halm EA. Sex differences in lung cancer survival: do tumors behave differently in elderly women? J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1705–1712.

- Sun Z, Aubry MC, Deschamps C, et al. Histologic grade is an independent prognostic factor for survival in non-small cell lung cancer: an analysis of 5018 hospital- and 712 population-based cases. J Thoracic Cardiovasc Surg. 2006;131:1014–1020.

- Sakao Y, Sakuragi T, Natsuaki M, et al. Clinicopathological analysis of prognostic factors in clinical IA peripheral adenocarcinoma of the lung. Ann Thoracic Surg. 2003;75:1113–1117.

- Ahrendt SA, Hu Y, Buta M, et al. p53 mutations and survival in stage I non-small-cell lung cancer: results of a prospective study. J Nat Cancer Inst. 2003;95:961–970.

- Inoue M, Sawabata N, Takeda S, et al. Results of surgical intervention for p-stage IIIA (N2) non-small cell lung cancer: acceptable prognosis predicted by complete resection in patients with single N2 disease with primary tumor in the upper lobe. J Thoracic Cardiovasc Surg. 2004;127:1100–1106.

- Vallbohmer D, Brabender J, Yang DY, et al. Sex differences in the predictive power of the molecular prognostic factor HER2/neu in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. Clin Lung Cancer. 2006;7:332–337.

- Chamogeorgakis T, Anagnostopoulos C, Kostopanagiotou G, et al. Does anemia affect outcome after lobectomy or pneumonectomy in early stage lung cancer patients who have not received neo-adjuvant treatment? Thoracic Cardiovasc Surg. 2008;56:148–153.

- Sawabata N, Miyoshi S, Matsumura A, et al. Prognosis of smokers following resection of pathological stage I non-small-cell lung carcinoma. General Thoracic Cardiovasc Surg. 2007;55:420–424.

- Yano T, Miura N, Takenaka T, et al. Never-smoking nonsmall cell lung cancer as a separate entity: clinicopathologic features and survival. Cancer. 2008;113:1012–1018.

- Foegle J, Hedelin G, Lebitasy MP, et al. Specific features of non-small cell lung cancer in women: a retrospective study of 1738 cases diagnosed in Bas-Rhin between 1982 and 1997. J Thoracic Oncol. 2007;2:466–474.

- Schwartz AM, Rezaei MK. Diagnostic surgical pathology in lung cancer: diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: American college of chest physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2013;143(5 suppl):e251S–e262S.

- Brunelli A, Charloux A, Bolliger CT, et al. ERS/ESTS clinical guidelines on fitness for radical therapy in lung cancer patients (surgery and chemo-radiotherapy). Eur Respir J. 2009;34:17–41.

- Batevik R, Grong K, Segadal L, et al. The female gender has a positive effect on survival independent of background life expectancy following surgical resection of primary non-small cell lung cancer: a study of absolute and relative survival over 15 years. Lung Cancer. 2005;47:173–181.

- Alberg AJ, Brock MV, Ford JG, et al. Epidemiology of lung cancer: diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2013;143(5 Suppl):e1S–29S.

- Jemal A, Travis WD, Tarone RE, et al. Lung cancer rates convergence in young men and women in the United States: analysis by birth cohort and histologic type. Int J Cancer. 2003;105:101–107.