Abstract

Background: The objective of this study was to examine if rehabilitation influenced self-reported male coping styles during and up to three years after treatment with radiotherapy for prostate cancer.

Materials and methods: In a single-center oncology unit in Odense, Denmark, 161 prostate cancer patients treated with radiotherapy and androgen deprivation therapy were included in a randomized controlled trial from 2010 to 2012. The trial examined the effect of a multidisciplinary rehabilitation program within six months of treatment consisting of two nursing counseling sessions and two instructive sessions with a physical therapist (n = 79), or standard care (n = 82). As secondary outcomes coping was measured before radiotherapy, one month after radiotherapy (baseline), six month post-intervention (assessment) and three years after radiotherapy (follow-up) by the Mini-mental adjustment to cancer scale (Mini-MAC). The male coping styles towards the illness are expressed in five mental adjustment styles: Fighting Spirit, Helplessness-Hopelessness, Anxious Preoccupation, Fatalism and Cognitive Avoidance. Descriptive analysis and multiple linear regression analysis adjusting for the longitudinal design were conducted.

Results: Most coping styles remained stable during the patient trajectory but Anxious Preoccupation declined from before radiotherapy to follow-up in both intervention and control groups. After six months the intervention group retained Fighting Spirit significantly (p = 0.025) compared with controls, but after three years this difference evened out. After three years the intervention group had lower Cognitive Avoidance (p = 0.044) than the controls. Factors as educational level, and depression influenced the use of coping styles after three years.

Conclusion: Multidisciplinary rehabilitation in irradiated prostate cancer patients retained the adjustment style Fighting Spirit stable after six months of radiotherapy, and in the long term reduced Cognitive Avoidance. Thus, the rehabilitation program supported the patient’s active coping style and played down the passive coping style.

Prostate cancer is the most common cancer among men [Citation1]. In Denmark 4577 men were diagnosed with prostate cancer in 2014. Due to increased incidence and improvements in treatment, more than 33 639 Danish men are living after a diagnosis of prostate cancer [Citation2]. About a third of all incident prostate cancer patients are treated with external radiotherapy, delivered with 39 fractions and a total of 78 Gy, which may cure patients with stage T1-T3 disease [Citation3]. Patients offered external radiotherapy have often locally advanced disease or are not fit for prostatectomy. External radiotherapy is usually preceded by three months of neo-adjuvant androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) and for high-risk patients’ adjuvant ADT may be continued for three years [Citation4].

In spite of improving 10-year survival rates to more than 70% [Citation4], prostate cancer patients are exposed for a number of challenges during the cancer trajectory. They have to cope with the diagnosis of a life-threating disease, and sometimes make difficult choices regarding treatment [Citation5]. During treatment the patients have to manage possible side effects, especially urinary and sexual problems, caused by disease or treatment, and may eventually manage and include late adverse effects into everyday life [Citation6,Citation7]. Prostate cancer patients have different unmet needs, and long-term unmet needs has been pointed out especially to be sexual morbidity; family issues, e.g. intimacy with partner; fear of cancer recurrence, and inadequate information about long-term effects of treatment [Citation8]. To deal with this in a proper way and with appropriate and timely supportive care or rehabilitation, we need to understand how men with prostate cancer are coping during the cancer trajectory. Limited research has been published describing coping in prostate cancer patients treated with radiotherapy and ADT. McSorley et al. reported in a mixed-method study that Irish men (n = 149) used different coping strategies during the first year after radiotherapy [Citation9]. The most used strategies were acceptance, positive framing, planning, emotional support and just getting on with it. A minority used alcohol, behavioral disengagement or self-blame [Citation9]. Cooper et al. studied quality of life (QoL) and coping styles in radiated Australian men with localized (n = 211) or advanced prostate cancer (n = 156) within the first year of diagnosis. They found that a fatalistic coping style near the time of diagnosis was predictor for a later depression in men with localized disease [Citation10]. However, these studies were short-term studies, and it is unknown how rehabilitation affects coping styles in radiated men with prostate cancer in the longer term. This paper presents secondary outcomes from a randomized controlled trial, the RePCa study, which showed rehabilitation to reduce irritative urinary problems within six months from radiotherapy [Citation11]. Furthermore, our hypothesis was that rehabilitation could strengthen the patients’ coping styles.

Here, we present data illustrating how rehabilitation influenced the patients coping styles and which factors influence prostate cancer survivor's coping styles during a long-term cancer trajectory.

Material and methods

Setting and participation

The RePCa study and this follow-up study was approved by the local Scientific Research Ethics Committee (File no. S-20090142), the Danish National Data Protection Agency (File no. 2012-41-1175), and registered by ClinicalTrials.gov (Study number, NCT01272648). All participants provided written informed consent and study procedures followed the Helsinki Declaration [Citation12].

Design

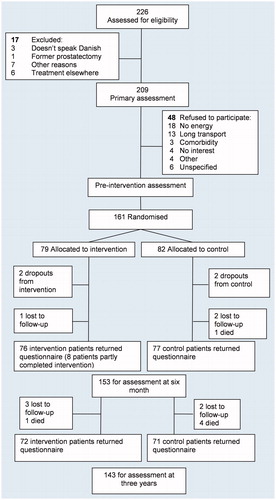

The design was a longitudinal prospective two-armed randomized controlled trial with follow-up, and recruited among 226 patients referred to curative radiotherapy from 1 February 2010 to 31 January 2012 at Odense University Hospital in Denmark. A total of 209 patients were eligible for participation ().

Figure 1. CONSORT-flow chart of a randomized study (RePCa) with follow-up in patients with prostate cancer.

Inclusion criteria: men ≥18 years old and with biopsy documented adenocarcinoma of the prostate.

Exclusion criteria: former prostatectomy, not able to speak Danish, or included in other protocols.

Information about TNM-staging, Gleason score, prostate-specific antigen values (PSA), and comorbidity was obtained from the patients’ medical files, and patients were registered in D’Amico risk groups [Citation13]. The treatment plan was external radiotherapy with intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT) with a dose of 78 Gy in 39 fractions given in 5 fractions per week. ADT was initiated three months before radiotherapy; and continued up to three years for high-risk patients.

Patients were randomly assigned to the intervention group or usual care (control group) in a ratio of 1:1 after completion of radiotherapy. The randomizations were externally handled, and the allocation sequence concealed from the research team.

The RePCa intervention

The rehabilitation intervention took place in an outpatient hospital setting and lasted from four weeks post-radiation to six months after radiotherapy.

The control group received usual care during follow-up, which consisted of one physician visit four weeks after radiotherapy. No systematically education or support for the control group was provided during the trajectory. In addition to usual care, the patients in the intervention group were instructed in an individually multidisciplinary program during two nursing counseling sessions and two sessions of counseling by physical therapists aiming the exact need of each patient. Each session lasted one hour including documentation.

The brief nursing intervention was in accordance with the framework for nursing by Patricia Benner and Judith Wrubel [Citation14], and the method of motivational interviewing [Citation15]. The nurses identified information needs about physical and mental adverse effects, established a rehabilitation plan based on the patients’ personal goals, and if needed, provided advice on lifestyle changes.

The brief instructive physiotherapeutic intervention was developed by the evidence of pelvic floor exercises which has improved post-prostatectomy urinary continence, post-micturition dribble, and erectile function [Citation16,Citation17]. The physical therapists identified the patient’s need for improved pelvic floor muscle function; general physical activity level, and recommended a self-training home program consisting of pelvic floor muscle exercises and exercises for the major muscle groups including muscle endurance, strength and balance exercises integrated in daily activities. The patient was recommended to bring his spouse along for all counseling and instructions in order to increase understanding and the possibility to cope. The 20 weeks of intervention were used to allow for muscle training and a change from ‘being a patient’ to being a ‘cancer survivor’. Details of the intervention are described elsewhere [Citation11].

To manage the intervention, the group of staff members (nurses and physiotherapists) were all enrolled in a six-day course with seven 45-minute lectures per day containing the topics prostate cancer and treatment, the male perspective, incontinence and the pelvic floor, sexuality, depression and fear of recurrence, social support, and finally the method of motivational interviewing [Citation15].

Outcome measures

Mental adjustment (coping) was measured four times during the trajectory; before radiotherapy, one month after radiotherapy (baseline), six month post-intervention and three years (follow-up) after radiotherapy by the questionnaire Mini-mental Adjustment to Cancer Scale (Mini-MAC) [Citation18]. Due to the possible relation between coping and depression we report results from a single question from Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite (EPIC-26): ‘How many problems did you have with depression the last 4 weeks?’ Additionally, three years after a few questions were asked about the RePCa intervention and the follow-up period: ‘Did you find the intervention useful?’ and ‘Did you miss anything during the follow-up period?’ with the possibilities to answer: Yes, No, Do not know.

The primary outcome in the RePCa study was defined as the urinary irritative sum-score based on the EPIC-26. Secondary outcomes included QoL from the Medical Outcome Study Short form-12 (SF-12), urinary incontinence, bowel, sexual and hormonal sum-scores by EPIC-26, and assessment of the male pelvic floor. The six month results from these outcomes are published elsewhere [Citation11]. Secondary outcomes regarding mental adjustment to cancer are reported in this paper.

Mini-MAC

Over the last decades, there has been a growing interest in coping with cancer. The most widely spread definition of coping is Lazarus and Folkman’s definition: ‘Constantly changing cognitive and behavioral efforts to manage specific external and/or internal demands that are appraised as taxing or exceeding the resources of the person’ [Citation19]. Related to Lazarus and Folkman’s theory of coping is the theory of mental adjustment to cancer, developed by Watson and Greer, where mental adjustment is defined as: ‘the cognitive and behavioral responses the patient makes to the diagnosis of cancer’ [Citation20]. It comprises the person’s assessment of the implications of cancer and furthermore the emotional reactions in relation to the disease. So, ‘mental adjustment’ is considered to be more comprehensive than coping, and therefore chosen for this study. However, Watson et al. use the mental adjustment styles for coping styles [Citation18], thus this term is used.

The MAC scale was developed in the UK to measure self-rated cognitive and behavioral responses of patients suffering from cancer [Citation20,Citation21]. The original MAC had 40 items to measure four adjustment styles. A new refined and shortened scale was developed in 1994 and called the Mini-MAC. This scale was extended with the possibility to measure Cognitive Avoidance as a coping style [Citation18]. The Mini-MAC is a 29-item four-point Likert Scale ranging from (1 = it definitely does not apply to me; to 4 = it definitely applies to me). The scale measures how the person is coping with cancer with regard to five coping styles with Cronbach’s alpha from 0.62 to 0.88 [Citation18].

Fighting Spirit – four items (the tendency to confront and actively face the illness, e.g. ‘I see my illness as a challenge’). Range 4–16 points.

Fatalism – five items (resigned and fatalistic attitudes about the illness, e.g. put themselves in the hands of God or fate and take one day at a time, e.g. ‘I’ve had a good life, what’s left is a bonus’). Range 5–20 points.

Cognitive Avoidance – four items (tendency to distract one-self about thoughts of illness and to avoid confrontation with it ‘Not thinking about it helps me cope’). Range 4–16 points.

Anxious Preoccupation – eight items (feelings of anxiety and the tendency of feeling over-worried concerning the illness, e.g. ‘I am a little frightened’). Range 8–32 points.

Helplessness-Hopelessness – eight items (the tendency to adopt a pessimistic attitude about the illness, e.g. ‘I feel like giving up’). Range 8–32 points.

The original factor structure was used to obtain scores on the five subscales. The raw scores are summed up for each subscale. A higher score represents a higher level of the respective coping style. The styles can be scored separately through simple addition, showing the total of each coping style.

The Mini-MAC is a validated and well known tool and in the Scandinavian cultural sphere, translated and validated in breast cancer patients in Norway [Citation22]. Furthermore, the Mini-MAC is used in a Swedish study of patients with laryngeal cancer [Citation23] and, in Denmark, in a study of women with breast cancer [Citation24].

The Mini-MAC was used with permission from Professor Maggie Watson [Citation18].

Statistical analyses

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics were described using means for continuous variables and frequencies for categorical variables. According to the methods described for Mini-MAC, all questions should be answered to be analyzed and insufficient questionnaires were removed from the analysis. Differences regarding coping styles between intervention and control groups were tested with multiple linear regression models adjusted for baseline (post-radiation) scores, and for three years data also adjusted for the post-intervention scores to consider the longitudinal design. All patients were analyzed with intention-to-treat according to the allocated group.

As secondary analyses, associations with the five coping styles at three years as dependent variables were analyzed for exposures, in this case: coping scores at baseline and at post-intervention, allocated group, age, education and self-reported moderate-severe depression. The purpose was to develop an explanatory model of the exposures, as previous research has shown these factors to influence coping [Citation25].

P-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant and were reported two-sided. Statistics were calculated with STATA 11.

Results

Participants

A total of 226 patients were screened for eligibility, and 48 patients refused to participate due to different reasons (). Groups were balanced at pre-intervention. The patients who refused to be included in RePCa differed by having a statistically significant, but marginally lower D'Amico risk, more patients were living alone, had a lower level of education and a higher proportion of smokers (). Patient flow is shown in , leaving 153 patients (95%) for the analysis at six months and 143 patients (89%) at three years. A total of 71/79 of the patients in the intervention group (90%) completed the entire intervention program. The attrition rate was 5% as four dropped out during intervention.

Table 1. Sociodemographic and biological pre-intervention characteristics of 161 participants and 48 non-participants with primary prostate cancer included in a randomized controlled trial after radiotherapy and androgen deprivation therapy, 2010–2012, Denmark.

Three years after, six patients had deceased, one from the intervention group and five from the control group. One patient allocated to the intervention group was diagnosed with relapse at three years follow-up in the outpatient clinic.

In response to the intervention and the follow-up period, 43 (60%) patients in the intervention group reported the intervention useful, four (5%) found it not useful and 25 (35%) did not know. Of all the patients at three year follow-up, 23 (16%) responded that they missed something in the follow-up period, 95 (68%) did not miss anything, and 23 (16%) did not know. There was no significant difference between patients from the intervention or control group.

Coping

At three years, the response rate with no missing items in coping styles was between 85% (Anxious Preoccupation and Cognitive Avoidance) to 87% (Fighting Spirit).

Most of the coping styles remained stable during the patient trajectory except Anxious Preoccupation, which declined for all patients from before to after radiotherapy (). After six months the intervention group retained Fighting Spirit significantly (p = 0.025) compared to controls, but after three years this difference evened out. After three years patients in the intervention group had significantly lower Cognitive Avoidance compared to controls – 1.07 (p = 0.044) ().

Table 2. Scores of mental adjustment styles pre-radiation, post-radiation, and post-intervention 6 months and 3 years after radiotherapy.

Secondary analyses with multiple regressions at three years (data not shown) showed that all five coping styles were significantly correlated with their previous coping scores. Fighting Spirit and Fatalism was unaffected by personal factors as age, educational level and self-reported moderate-severe depression.

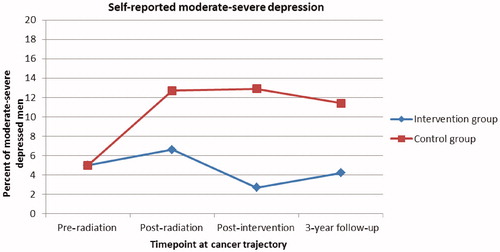

The use of Cognitive Avoidance was reduced in men with a medium educational level (–1.3, CI –2.5; –0.1, p = 0.029). Anxious Preoccupation increased with (3.8, CI 1.8; 5.8, p < 0.000) in moderate-severe depressed men. At three years follow-up, these men constituted 11/142 (7.8%) (). Medium level education influenced Anxious Preoccupation with −1.5 (CI −3.0; −0.2, p = 0.029), and Helplessness-Hopelessness was significantly increased in moderate-severe depressed men (2.1, CI 0.2; 3.9, p = 0.029).

Discussion

We found that rehabilitation consisting of nursing consultations and guidance from a physical therapist within six months from radiotherapy supported the active coping style Fighting Spirit in the short term, and in the long term reduced Cognitive Avoidance. However, the changes were small and may not be clinical important.

Fighting Spirit is the tendency to confront and actively face the illness [Citation18], and Fighting Spirit has previously been linked to low levels of psychopathology [Citation20]. This active coping style may be important in a self-management approach like the RePCa intervention. However, after three years this difference evened out. After three years the intervention group showed significantly lower Cognitive Avoidance than controls. Roesh et al. have in a review with mixed prostate cancer patients (n = 3133) concluded that Cognitive Avoidance heightened negative psychological adjustment [Citation25]. Still, most coping style studies included women with breast cancer, and the way men cope may be different. Nonetheless, during the rehabilitation, the men in the intervention group may have learned the advantages of talking to others. The clinical meaningfulness for prostate cancer patients to discuss with professionals and in particular with peers how to cope was confirmed in focus groups [Citation26]. Therefore, this intervention could be considered for future rehabilitation. Furthermore, the data showed men better educated were less likely to use Cognitive Avoidance, possibly explained by a higher tendency for educated persons to seek information.

Men who were moderate-severe depressed were more likely to use Anxious Preoccupation and Helplessness-Hopelessness as a coping style. Dalton et al. have shown that prostate cancer patients face an 81% increase in hospitalization due to depression the first 10 years after diagnosis [Citation27], and treatment with ADT may cause some of the blame [Citation28]. It is therefore important to be aware of the association between prostate cancer patients’ ability to cope and depression. Cooper et al. showed a fatalistic coping style to predict a later depression measured by HADS [Citation10], but we did not find the same association using EPIC-26. However, the single question used about depression in EPIC-26 must be a weaker measure compared to HADS, which is specifically designed to measure anxiety and depression. We did not examine associations between coping styles and other QoL factors than depression, and this remain to be investigated.

The coping styles remained almost stable during the trajectory although the measurement points represented quite different situations. However, a limitation to the study could be that the Mini-MAC may not be sensitive enough to catch minor changes over time. In addition, as 16% of all the patients responded that they missed something during their follow-up, it is important to explore what these issues are. A limitation is that the Danish version of the Mini-MAC has not been psychometric tested. The original five-factor structure has been questioned by Bredal et al. who suggested a four-factor structure, which combines Fighting Spirit and the Fatalism subscales into a ‘positive attitude’ adjusting style [Citation22]. However, as underlined by Ho et al., Fatalism in the original Mini-MAC is presumed to measure a patient’s tendency to accept the situation as unavoidable or ‘fate’, and should be conceptually separated from Fighting Spirit, which measure a patient’s tendency to take active steps to try to cure the disease or to ameliorate its effects [Citation29].

After treatment for prostate cancer, unmet needs related to intimacy, information, physical and psychological needs are reported [Citation8]. In clinical practice, this knowledge about unmet needs may be relevant to connect with an identification of the patient’s ability to cope. This could, for example be done by systematically patient-reported outcome measures during the cancer trajectory, and a dialogue between patients, family and health professionals, focusing at the moderate-severe problems and how they cope. However, health professionals involved in prostate cancer follow-up care should be aware that men use a variety of coping styles [Citation9].

This study has a number of advantages. The longitudinal design allowed us to follow the same patients at different time points from before treatment to three years follow-up. Internal validity in the RePCa study was maintained by randomization and the homogeneity of the groups. The study provided good feasibility with a high inclusion rate, few drop outs and a high response rate even after three years. The unrestricted inclusion and exclusion criteria, the uniform treatment protocol, and the fact that the included men were living in cities as well as rural areas, allow generalization of the results as the study sample was representative of a population of irradiated prostate cancer patients in Denmark.

To apply knowledge of men’s different coping styles in clinical practice will require training, resources and commitment through the rehabilitation and the follow-up period, and innovative thinking of inclusion of the family, especially partners, peers and municipal caregivers in the psychosocial support.

Conclusion

Multidisciplinary rehabilitation in irradiated prostate cancer patients retained Fighting Spirit stable after six months of radiotherapy, but this difference between groups was not present at follow-up. After three years, the intervention group used lower Cognitive Avoidance than controls. Thus, the rehabilitation program supported the patients’ active coping style and played down the passive coping style.

Acknowledgments

A special thanks to the patients who participated in the study for their valuable contributions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:E359–E386.

- Sundhedsdatastyrelsen. Nye kræfttilfælde i Danmark, Cancerregisteret 2014. Copenhagen: Sundhedsdatastyrelsen; 2014.

- Harmenberg U, Hamdy FC, Widmark A, et al. Curative radiation therapy in prostate cancer. Acta Oncol. 2011;50(Suppl 1):98–103.

- Widmark A, Klepp O, Solberg A, et al. Endocrine treatment, with or without radiotherapy, in locally advanced prostate cancer (SPCG-7/SFUO-3): an open randomised phase III trial. Lancet. 2009;373:301–308.

- Gwede CK, Pow-Sang J, Seigne J, et al. Treatment decision-making strategies and influences in patients with localized prostate carcinoma. Cancer. 2005;104:1381–1390.

- Budäus L, Bolla M, Bossi A, et al. Functional outcomes and complications following radiation therapy for prostate cancer: a critical analysis of the literature. Eur Urol. 2012;61:112–127.

- Dieperink KB, Hansen S, Wagner L, et al. Living alone, obesity and smoking: important factors for quality of life after radiotherapy and androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. Acta Oncol (Stockholm, Sweden). 2012;51:722–729.

- Paterson C, Robertson A, Smith A, et al. Identifying the unmet supportive care needs of men living with and beyond prostate cancer: a systematic review. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2015;19:405–418.

- McSorley O, McCaughan E, Prue G, et al. A longitudinal study of coping strategies in men receiving radiotherapy and neo-adjuvant androgen deprivation for prostate cancer: a quantitative and qualitative study. J Adv Nurs. 2014;70:625–638.

- Couper JW, Love AW, Duchesne G, et al. Predictors of psychosocial distress 12 months after diagnosis with early and advanced prostate cancer. Med J Aust. 2010;193(5 Suppl):58–61.

- Dieperink KB, Johansen C, Hansen S, et al. The effects of multidisciplinary rehabilitation: RePCa-a randomised study among primary prostate cancer patients. Br J Cancer. 2013;109:3005–3013.

- World Medical Association. World Medical Association declaration of Helsinki; 2008. Available from: http://www.wma.net/en/30publications/10policies/b3/index.html

- D'amico A, Whittington VR, Malkowicz S, et al. Biochemical outcome after radical prostatectomy, external beam radiation therapy, or interstitial radiation therapy for clinically localized prostate cancer. JAMA. 1998;280:969–974.

- Benner P, Wrubel J. The primacy of caring. stress and coping in health and illness. Menlo Park, CA: Addison-Wesley; 1989.

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing, preparing people to change addictive behavior. New York: The Guildford Press; 2002.

- Van Kampen M, Weerdt W, Van Poppel DH, et al. Effect of pelvic-floor re-education on duration and degree of incontinence after radical prostatectomy: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2000;355:98–102.

- MacDonald R, Fink HA, Huckabay C, et al. Pelvic floor muscle training to improve urinary incontinence after radical prostatectomy: a systematic review of effectiveness. BJU Int. 2007;100:76–81.

- Watson M, Law M, dos Santos M, et al. The Mini-MAC: further development of the Mental Adjustment to Cancer Scale. J Psychococ Oncol. 1994;12:33–46.

- Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal and coping. New York: Springer Publishing Company; 1984.

- Watson M, Greer S, Young J, et al. Development of a questionnaire measure of adjustment to cancer: the MAC scale. Psychol Med. 1988;18:203–209.

- Greer S, Watson M. Mental adjustment to cancer: its measurement and prognostic importance. Cancer Surveys. 1987;6:439–453.

- Bredal IS. The Norwegian version of the Mini-Mental Adjustment to Cancer Scale: factor structure and psychometric properties. Psychooncology. 2010;19:216–221.

- Johansson M, Ryden A, Finizia C. Mental adjustment to cancer and its relation to anxiety, depression, HRQL and survival in patients with laryngeal cancer: a longitudinal study. BMC Cancer. 2011;11:283.

- Rottmann N, Dalton SO, Christensen J, et al. Self-efficacy, adjustment style and well-being in breast cancer patients: a longitudinal study. Qual Life Res. 2010;19:827–836.

- Roesch SC, Adams L, Hines A, et al. Coping with prostate cancer: a meta-analytic review. J Behav Med. 2005;28:281–293.

- Dieperink KB, Wagner L, Hansen S, et al. Embracing life after prostate cancer. A male perspective on treatment and rehabilitation. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2013;22:549–558.

- Dalton SO, Laursen T, Ross ML, et al. Risk for hospitalization with depression after a cancer diagnosis: a nationwide, population-based study of cancer patients in Denmark from 1973 to 2003. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1440–1445.

- Dinh KT, Reznor G, Muralidhar V, et al. Association of androgen deprivation therapy with depression in localized prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:1905–1912.

- Ho SM, Fung WK, Chan C, et al. Psychometric properties of the Chinese version of the Mini-Mental Adjustment to Cancer (MINI-MAC) scale. Psychooncology. 2003;12:547–556.