Sir,

In the field of oncology, the concept of ‘distress’ refers to ‘a multifactorial unpleasant emotional experience of a psychological (i.e., cognitive, behavioral, emotional), social and/or spiritual nature that may interfere with the ability to cope effectively with cancer, its physical symptoms, or its treatment. Distress extends along a continuum, ranging from common normal feelings of vulnerability, sadness and fears to problems that can become disabling such as depression, anxiety, panic, social isolation and existential and spiritual crisis’ [Citation1]. Defining and measuring distress is part of a strong emancipatory movement that aims to provide adequate psychosocial care for patients with cancer [Citation2].

However, the current concept of cancer-related distress is not founded on modern conceptualizations of emotions and mental disorders. Furthermore, accumulating empirical studies report inconsistent uptake of interventions for distress. Therefore, we would argue that the conceptualization of cancer-related distress needs to be reconsidered, for both theoretical and empirical reasons.

Adaptive and maladaptive emotional responses

Although the definition of distress does acknowledge ‘common normal feelings’, it emphasizes the need for treatment: ‘distress should be recognized, monitored, documented and treated promptly at all stages of disease and in all settings’ [Citation1]. This definition tends to ignore the fundamental adaptive value of emotions.

Emotions have developed through the course of the evolution, as they facilitate adaptation to important events [Citation3]. Emotions alert, motivate and prepare us to deal with these events [Citation4]. For example, fear causes cognitive shifts, prioritizing efforts to cope with the threatening event; through overt behavioral responses we attempt to cope with a threatening event; physiological changes associated with fear prepare and support these behavioral responses [Citation3]. Sadness also carries important adaptive value. Sadness turns our attention inwards, promoting resignation and acceptance; physiological arousal is decreased, which contributes to reflection and adaptation of goals; the expression of sadness may elicit sympathy and support from other people [Citation5].

Mental disorders are characterized by lack of adaptation. A mental disorder, such as anxiety disorder or major depressive disorder, is defined as ‘a syndrome characterized by clinically significant disturbance in an individual's cognition, emotion regulation, or behavior that reflects a dysfunction in the psychological, biological, or developmental processes underlying mental functioning’ [Citation6]. A mental disorder interferes with adaptation, leading to significant distress and disability.

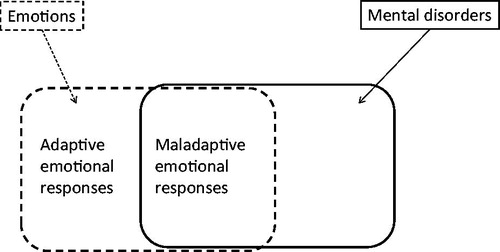

Emotions and mental disorders are strongly related. In a quantitative meta-analysis, emotional inertia (emotional states that linger and perpetuate over time) was associated with the presence of mental disorders, including anxiety and depressive disorders [Citation7]. High emotional variability (extreme states and large amplitudes of emotions) as well as emotional instability (emotional shifts from one moment to the next) were also associated with the presence of mental disorders. Thus, both lack (emotional inertia) and excess in emotional reactivity (extreme emotional states and emotional instability) are related to mental disorders, while smaller emotional changes are related to better mental health. Houben et al. [Citation7] comment: ‘Adaptive emotional functioning (…) <is> reminiscent of, for instance, the smaller back and forth jumps a tennis player makes when preparing to counter a serve, or the constant small adjustments we make to remain standing upright.’ The distinction between adaptive and maladaptive emotions is illustrated in .

This analysis leads us to formulate two hypotheses. (i) Emotional responses to the diagnosis and treatment of cancer are adaptive, unless these emotions are extreme or unstable. Cancer-related emotions – even if they have a negative valence – carry the potential to facilitate effective adaptation (e.g., by increasing adherence to medical regimens, or by eliciting social support). (ii) We further hypothesize that emotional responses to the diagnosis and treatment of cancer are maladaptive if these responses linger and perpetuate across time (emotional inertia), if these responses are extreme and unstable (emotional variability and instability), or if these responses interfere with the ability to cope with cancer, leading to significant distress and disability.

Indicators of adaptive and maladaptive emotional responses

Identification of patients with clinically relevant distress is based on the intensity of emotional responses [Citation1]. Measurement instruments such as the Distress Thermometer use a cutoff score for the intensity of emotional responses; patients are identified as suffering from distress if they score above the cutoff [Citation1].

This approach to measuring distress is built on the assumption that a low intensity of emotional responses is to be preferred, i.e., ‘less is better’. We argue that a cutoff on the dimension of intensity of emotional responses is not a valid approach. Indeed, some patients scoring above the cutoff may experience maladaptive emotional responses. However, other patients scoring above the cutoff may actually experience adaptive emotional responses, which facilitate coping with cancer.

The development of valid indicators distinguishing between adaptive and maladaptive emotional responses is an urgent research priority, both in general and in the field of psycho-oncology in particular. Candidate indicators are emotional inertia; emotional variability and instability, or lack of emotional regulation [Citation7,Citation8]; and emotional responses that interfere with the patient’s ability to cope with cancer [Citation6].

Uptake of interventions for distress

The current guidelines on distress management recommend that the primary oncology team (i.e., doctors and nurses) should deal with mild distress, defined as distress scores below the accepted cutoff score [Citation1]. Patients scoring above the cutoff score need to be further clinically assessed, which may result in a referral to a mental health professional. Despite its intuitive appeal, this approach results in important empirical inconsistencies in the uptake of distress interventions.

The majority of patients scoring above the cutoff for distress reportedly decline professional intervention. In a UK-based study, only 36% of patients with elevated distress scores indicated a need for professional help with emotional problems [Citation9]. An Australian study found that only 30% of distressed patients reported a need for help with distress [Citation10]. In a USA-based study, screening was implemented to identify patients with distress: from the patients screening positive on distress, only 14% had actually completed at least one appointment with the supportive care team after 14 days follow-up [Citation11].

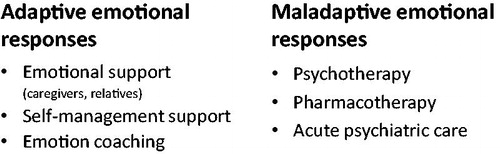

We would argue that the distinction between adaptive and maladaptive emotional responses may aid to understand the low uptake of interventions for distress. Patients who experience maladaptive emotional responses are indeed in need of professional mental health care, defined as psychotherapy, pharmacotherapy or emergency psychiatric care. Patients who experience adaptive emotional responses are hypothesized not to be in need of professional mental health care. Instead, they need support from relatives, friends and primary care-givers (i.e., doctors and nurses), and possibly other interventions that help them to deal with emotions (see below). The nature rather than the intensity of emotional responses seems to determine the need for professional mental health care. This would explain why many patients scoring above the cutoff for distress decline contact with a mental health professional.

Further inconsistencies in the uptake of interventions have been observed. Brebach et al. [Citation12] reviewed the uptake of psychological interventions designed to reduce distress, anxiety, depression, or fear of cancer recurrence. The review included 53 studies. The authors were surprised to find (i) that uptake was lower in studies that recruited patients scoring above the cutoff for distress, compared to studies that recruited unselected patients, and (ii) that uptake was lower if the study offered definitive psychological intervention (e.g., a study comparing two different interventions), compared to studies that carried the chance of assignment to a nonintervention condition (e.g., usual care). We would argue that the Brebach findings can be understood from the perspective of adaptive emotions. (i) Recruiting patients scoring above the cutoff for distress may lead to a low uptake, because a substantial number of patients may be experiencing adaptive emotional responses, leading them to decline professional support. (ii) Patients who do not experience a need for professional care may actually prefer the chance of assignment to a nonintervention condition, as opposed to the ‘risk’ of a definite offer of psychological intervention.

Tailoring of interventions

Patients experiencing adaptive emotions may need support other than traditional mental health care. Emotional support, defined as empathy, concern, encouragement, caring and affection [Citation13,Citation14] has been shown to improve health and well-being [Citation15,Citation16]. It is therefore important that, besides direct relatives, doctors and nurses provide emotional support [Citation17]. Greenberg [Citation18] has proposed ‘emotion coaching’ as an approach towards working with emotions. Instead of treating and reducing emotional responses, this approach encourages awareness of and reflection on emotions. Supporting patients in self-management also needs to be distinguished from traditional psychotherapeutic or psychiatric treatment. For example, after completion of primary treatment a self-management program strengthened patients in their capacity to use their emotions to adapt to the new situation, as opposed to ‘treating’ or ‘eliminating’ emotional responses [Citation19].

We contend that interventions need to be tailored to the nature of the emotional responses (see ). Emotional support, emotional coaching and self-management support are primarily indicated to help patients dealing with adaptive emotions. Traditional mental health care (i.e., psychotherapy, pharmacotherapy and in-patient emergency psychiatric care) is indicated in case of maladaptive emotions.

It should be noted that this model differs fundamentally from the well-known tiered model of psychosocial interventions in oncology [Citation20]. The tiered model tailors to the intensity of distress, while we have argued that it is not the intensity but the nature of the emotional responses that should be considered.

Conclusion

The concept of cancer-related distress has strongly contributed to the development of the field of psychosocial cancer care. The time has now come for a reconceptualization of distress, for both theoretical and empirical reasons. Distinguishing between adaptive and maladaptive emotional responses may contribute significantly to the understanding of cancer-related distress. Developing valid indicators of adaptive and maladaptive emotional responses is an urgent research priority. Interventions need to be tailored to the nature of emotional responses (adaptive versus maladaptive emotions), instead of their intensity. We believe that our analysis constitutes an important agenda for future empirical research.

Disclosure statement

Aartjan T.F. Beekman – Speakers’ Bureau: Lundbeck, Eli Lilly.

Additional information

Funding

References

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Guideline Distress Management Version 1; 2016. NCCN [Internet]. Available from: www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/f_guidelines.asp#distress

- International Psycho-Oncology Society; 2016. Available from: http://ipos-society.org/

- Tooby J, Cosmides L. The evolutionary psychology of the emotions and their relationship to internal regulatory variables. In: Lewis M, Haviland-Jones JM, Feldman Barrett L, editors. Handbook of emotions. New York: The Guilford Press; 2010. p. 114–137.

- Frijda NH. The emotions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1986.

- Bonanno GA, Goorin I, Coifman KG. Sadness and grief. In: Lewis M, Haviland-Jones JM, Feldman Barrett L, editors. Handbook of emotions. New York: The Guilford Press; 2010. p. 797–810.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Arlington (VA): American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

- Houben M, Van Den Noortgate W, Kuppens P. The relation between short-term emotion dynamics and psychological well-being: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull. 2015;141:901–930.

- Gross JJ. Handbook of emotion regulation. New York: The Guilford Press; 2007.

- Baker-Glenn EA, Park B, Granger L, et al. Desire for psychological support in cancer patients with depression or distress: validation of a simple help question. Psychooncology. 2011;20:525–531.

- Clover K, Kelly P, Rogers K, et al. Predictors of desire for help in oncology outpatients reporting pain or distress. Psychooncology. 2013;22:1611–1617.

- Funk R, Cisneros C, Williams RC, et al. What happens after distress screening? Patterns of supportive care service utilization among oncology patients identified through a systematic screening protocol. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24:2861–2868.

- Brebach R, Sharpe L, Costa DS, et al. Psychological intervention targeting distress for cancer patients: a meta-analytic study investigating uptake and adherence. Psychooncology. 2016;25:882–890.

- Langford CP, Bowsher J, Maloney JP, et al. Social support: a conceptual analysis. J Adv Nurs. 1997;25:95–100.

- Slevin ML, Nichols SE, Downer SM, et al. Emotional support for cancer patients: what do patients really want? Br J Cancer. 1996;74:1275–1279.

- Cohen S, Symme SL. Social support and health. San Diego (CA): Academic Press; 1985.

- Lepore S. A social–cognitive processing model of emotional adjustment to cancer. In: Baum A, Andersen B, editors. Psychosocial interventions for cancer. Washington (DC): American Psychological Association; 2001. p. 99–116.

- Holland JC, Lewis S. The human side of cancer. New York: HarperCollinss; 2001.

- Greenberg LS. Emotion-focused therapy: coaching clients to work through their feelings. Washington (DC): American Psychological Association; 2002.

- van den Berg SW, Gielissen MF, Custers JA, et al. BREATH: web-based self-management for psychological adjustment after primary breast cancer-results of a multicenter randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:2763–2771.

- Hutchison SD, Steginga SK, Dunn J. The tiered model of psychosocial intervention in cancer: a community based approach. Psychooncology. 2006;15:541–546.