Abstract

Background: We were interested in examining if there was a link between self-assessed emotional shock by prostate cancer diagnosis and psychological well-being at 3, 12, and 24 months after surgery.

Material and methods: Information was derived from patients participating in the LAPAroscopic Prostatectomy Robot Open (LAPPRO) trial, Sweden. We analyzed the association between self-assessed emotional shock upon diagnosis and psychological well-being by calculating odds ratios (ORs).

Results: A total of 2426 patients (75%) reported self-assessed emotional shock by the prostate cancer diagnosis. Median age of study participants was 63. There was an association between emotional shock and low psychological well-being after surgery: adjusted OR 1.7: (95% confidence interval [CI]), 1.4–2.1 at 3 months; adjusted OR 1.3: CI, 1.1–1.7 at 12 months, and adjusted OR 1.4: CI, 1.1–1.8 at 24 months. Among self-assessed emotionally shocked patients, low self-esteem, anxiety, and having no one to confide in were factors more strongly related with low psychological well-being over time.

Conclusion: Experiencing self-assessed emotional shock by prostate cancer diagnosis may be associated with low psychological well-being for up to two years after surgery. Future research may address this high rate of self-assessed emotional shock after diagnosis with the aim to intervene to avoid this negative experience to become drawn out.

Background

With the widespread cancer fear in western society today, it is understandable that men may feel frightened upon receiving a prostate cancer diagnosis [Citation1], an experience which in turn may result in self-assessed emotional shock. According to a review article, several studies have focused on prostate cancer-specific distress during the first year after surgery [Citation2]. Yet less is known about the prevalence of self-assessed emotional shock at the diagnostic phase. Although one well-designed study indicates that receiving the diagnosis in an impersonal way is a major source of dissatisfaction with care [Citation3], we know very little of the extent to which the experience of self-assessed emotional shock at diagnosis is associated with patients’ well-being and whether it is associated with well-being over time. Shock may encompass both physical symptoms (e.g., shivers, feeling cold) as well as emotional symptoms (e.g., anxiety and worry) and it comprises both objective and subjective components. Typically, it is the subjective experience of objective events that make up the trauma [Citation4], like the situation when receiving a prostate cancer diagnosis. Hence, based on the subjective nature of the traumatic experience, emotional shock was for this report defined as the individual's own perception of feeling emotionally shocked.

We investigated the association between self-assessed emotional shock upon diagnosis and psychological well-being over time at four measurement points: from the preoperative phase to two years after radical prostatectomy. Our primary hypothesis was that patients who reported self-assessed emotional shock upon diagnosis of prostate cancer were more likely to report low psychological well-being at 3, 12, and 24 months after surgery. With the possibility to improve future care and possibly buffer against experiencing self-assessed emotional shock at diagnosis, our secondary hypothesis was that potentially modifiable psychosocial factors like self-esteem, that is, the emotional evaluation of one’s self worth, anxiety [Citation5,Citation6], and the ability to express emotions [Citation7] may also play a role on patients’ psychological well-being and interact on the association of self-assessed emotional shock with long-term psychological well-being.

Material and methods

Study population for this project derives from the LAPAaroscopic Prostatectomy Robot Open trial (LAPPRO), which is a prospective, nonrandomized, clinical controlled trial with the main purpose to compare outcomes after open retropubic and robot-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy at 14 Swedish urology departments performed between 1 September 2008 and 7 November 2011 [8] (ISRCTN registry no. 066393679). In the study reported here, those patients were included who had signed informed consent, were able to read and write Swedish, and who had responded to the question of self-assessed emotional shock upon diagnosis in the preoperative questionnaire.

Questionnaires were carefully prepared in accordance with an established methodology [Citation9,Citation10], which comprised in-depth patient interviews with content analysis, construction of questions by experts in the field that were based on thematic results from the in-depth interviews, and repeated face-to-face validations and questionnaire revisions with experts and patients to ensure the questions were understood as intended [Citation11]. When revised several times, we conducted a pilot study with an additional 10 patients. Thus, the clinimetric one-phenomenon-one-question tradition does not work with ‘constructs’ (the summing of items into one construct). Instead, we study self-assessed emotional shock with one question the way it was defined by the specific patient group in focus of the study, which is different from studying, for example, post-traumatic stress syndrome (PTSD), requiring a diagnosis by a physician or by an instrument assessing that specific ‘construct’. In the LAPPRO study, data were collected prospectively: preoperatively, and at 3, 12, and 24 months postoperatively. Also, clinicians documented information on record forms at each measurement time point. All means for data collection were standardized. A description of the trial and data collection procedure has been published previously [Citation12]. Prior to analyses for this report, a detailed analysis plan with definitions of all variables and predetermined dichotomizations was written. These were based on clinical experience with the patient group but also on previously used methodology from the LAPPRO cohort [Citation8].

The independent variable, self-assessed emotional shock upon diagnosis, was measured by the question ‘It is common to experience feeling emotionally shocked upon receiving a prostate cancer diagnosis. How well does this apply to you?’ with an ordinal scale of the following response categories ‘It doesn't apply to my experience at all’; ‘It applies somewhat to my experience’; ‘It applies a great deal to my experience’; and ‘It applies completely to my experience’. Since we aimed at investigating the association between any degree of self-assessed emotional shock upon diagnosis and psychological well-being, we classified ‘Somewhat’, ‘A great deal’, and ‘Completely’ as experiencing emotional shock upon diagnosis. To evaluate the outcome psychological well-being, we analyzed responses to the question ‘In the past month, how would you rate your psychological well-being?’ with a seven-digit visual digital scale (VDS) in which zero denoted ‘lowest possible well-being’ and six denoted ‘best possible well-being.’ We classified a response of 0–4 to be in the low well-being category, whereas a 5–6 response was classified as high well-being. Receiving the diagnosis was defined as receiving information by the urologist of a diagnosis of prostate cancer – a diagnosis warranting a discussion with the patient about treatment options where radical prostatectomy was one option. Cutoff levels were selected prior to conducting analyses and were based on patients' feedback in the face-to-face validations, clinicians' experience with the patient group, and on theory and prior knowledge of this patient group from the literature.

A chi-square test was used to estimate to which extent a difference between the two groups was statistically significant. To assess the bivariate relationships between possible psychosocial independent variables and psychological well-being in the group of patients reporting self-assessed emotional shock upon diagnosis, we used log-binomial regression analysis. Percentages of respondents in each category of the independent variables were calculated with psychological well-being and we formed ratios of these percentages (relative risks, RRs) as a measure of the strength of the link between the possible independent variable and psychological well-being (95% confidence interval (CI)). Using logistic regression, results were adjusted for age, marital status, educational level, alcohol intake, type of surgery, health status according to American Society of Anesthesiologists score (ASA), having someone to confide in, anxiety, feelings of depression, biochemical recurrence status, current erectile dysfunction, and current urinary leakage at the different time points. Covariates to adjust for were selected based on current literature and clinical experience with this patient group. As we suspected that self-assessed emotional shock by the diagnosis could depend upon severity of the tumor (tumor stage), we conducted a separate analysis to elucidate tumor stage as possibly associated with self-assessed emotional shock. Patients who had received their diagnosis at an earlier point and had therefore been on active surveillance were analyzed separately [Citation13]. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 for Windows (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). The study was approved by the Regional Ethics Committee (EPN Gothenburg 277-07).

Results

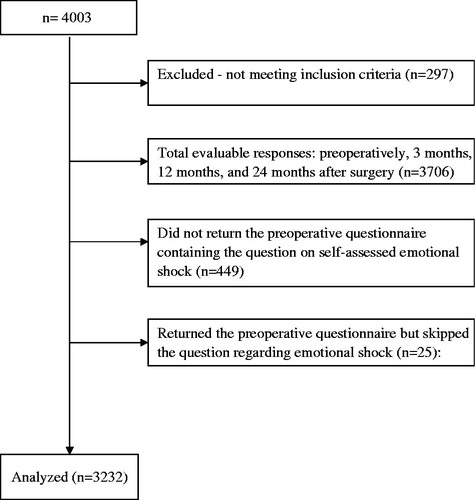

Analyses for this study included 3232 patients (). Out of those who returned the preoperative questionnaire, median age was 63 and 64 years, respectively, for the two groups self-assessed emotionally shocked and not emotionally shocked (). A sizeable number of patients in both groups were university educated (n = 874; 36% and n = 349; 43%). The second largest group in the study had completed secondary school. Fifty-four percent out of those who reported self-assessed emotional shock had their primary source of income from employment (n = 1301) and the proportion among patients not reporting self-assessed emotional shock among those employed was 49%. In addition to a higher Gleason score, self-assessed emotionally shocked patients were statistically significantly younger, had shorter education, were employed, and more anxious than patients not emotionally shocked (). According to a three parts division of d'Amico risk groups for the overall cohort, 412 patients were high risk (11%), 2198 were medium risk (60%), and 1032 were low risk (28) (data not shown in table).

Figure 1. Flow chart for the analysis of self-assessed emotional shock and psychological well-being from the LAPPRO trial.

Table 1. Characteristics of patients treated with radical prostatectomy (n = 3232).

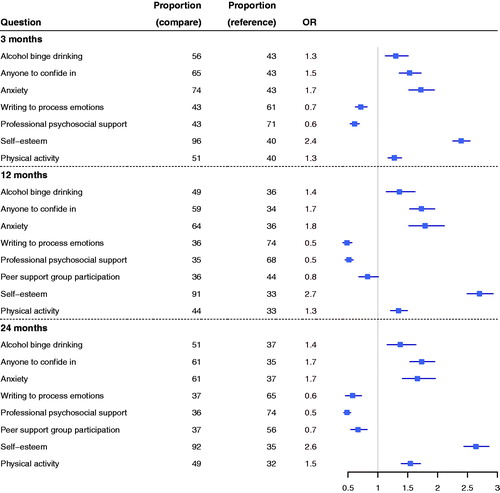

Two thousand four hundred twenty-six patients (75%) reported feeling emotionally shocked upon receiving their prostate cancer diagnosis and 806 patients (25%) reported not feeling shocked (). Adjusted results using log-binomial regression analysis show that self-assessed emotional shock from receiving the diagnosis increased one’s risk of low psychological well-being at 3 months (OR [odds ratio] 1.7; 95% CI, 1.4–2.0), at 12 months (OR 1.3; 95% CI, 1.1–1.7), and at 24 months after surgery (OR 1.4; 95% CI, 1.1–1.8) (). A separate analysis to elucidate the relationships between various aspects of tumor stage as possibly associated with self-assessed emotional shock showed statistically significant relationships for cT stage, tumor size ≥16 millimeters, and a high risk d'Amico score (). shows the potentially amenable psychosocial variables that were included in the model in order to investigate if they could be attributed to the association between self-assessed emotional shock and psychological well-being. Among patients reporting self-assessed emotional shock, self-esteem, anxiety, and having no one to confide in were the three factors most strongly associated with low psychological well-being at the different measurement points 3, 12, and 24 months after surgery ().

Figure 2. Potentially modifiable psychosocial independent variables of psychological well-being (outcome) at 3, 12, and 24 months after surgery among self-assessed emotionally shocked patients (n = 2426).

Table 2. Relative risks of self-assessed emotional shock upon diagnosis on low compared with high psychological well-being at 3, 12, and 24 months after radical prostatectomy.

Table 3. Relative risks of self-assessed emotional shock in relation to tumor characteristics.

Discussion

In this prospective controlled trial with patients having undergone radical prostatectomy by either open or robot assisted laparoscopic approach, we found that for up to two years following surgery, patients who reported feeling emotionally shocked by their prostate cancer diagnosis reported low psychological well-being in comparison with patients not emotionally shocked. We also found that among the emotionally shocked patients, low self-esteem, anxiety, and not having anyone to confide in were the factors most strongly related to low psychological well-being at 3, 12, and 24 months.

Our result that self-assessed emotional shock at diagnosis was associated with patients' psychological well-being for up to two years after surgery, maps on to the meager but consistent literature suggesting that male patients tend to be emotionally affected when receiving the prostate cancer diagnosis. In a qualitative publication from 2004, Wall et al. interviewed patients twice (n = 8): directly following recruitment to the study at diagnosis and three months thereafter, focusing on patients’ experiences during the first three months following prostate cancer diagnosis [Citation1]. All patients in their study reported feeling emotionally shocked upon diagnosis, the effects of which later on were studied as distress. Authors attributed this and the reported distress following diagnosis to the perceived need to camouflage their distress to friends and family because they believed that it was expected from them. Additional research has shown that a prostate cancer diagnosis may, by its very nature, make patients feel dependent, powerless, and incapable of caring for themselves [Citation14]. With these findings as backdrop, we speculate that the perceived need to maintain the role of ‘the strong one’ and not show emotions, the man avoids talking things out, but that this in turn, possibly makes him even more vulnerable to low psychological well-being.

Our results also showed that for those reporting self-assessed emotional shock, low self-esteem, increased anxiety, and having no one to confide in were the potentially amenable psychosocial factors most strongly associated with low psychological well-being at 3, 12, and 24 months after surgery with elevated odds ratios for all four factors at 12 months. It may be difficult to maintain a high self-esteem when facing the challenges that a prostate cancer diagnosis imposes, yet the patients experiencing self-assessed emotional shock in combination with low self-esteem may be those who need a psychosocial intervention the most. Helgeson et al. investigated if self-esteem, self-efficacy, and baseline depressive symptoms moderated the benefits of a psychoeducational intervention for patients with prostate cancer (n = 250) [Citation15]. In this study, using the 10-item Rosenberg Global Self-Esteem Scale at baseline, they found that the benefits of the intervention were strongest for patients with low self-esteem. Also, this was the most consistent finding across their measured outcomes and across time in the study [Citation15]. Understandably, the struggle with self-esteem may also parallel anxiety, a concern that has been well documented previously both in patients undergoing radical prostatectomy and in patients during active surveillance [Citation5,Citation11,Citation16]. With male patients typically maintaining one primary source of support, most often one's partner [Citation17], it is understandable that having no one to confide in was also one of the factors most strongly associated with low psychological well-being over time in the group of emotionally shocked patients.

It is possible that the separate analysis showing statistically significant relationships between various aspects of tumor stage (cT stage, ≥16 mm tumor length, and a high risk d’Amico score) and self-assessed emotional shock may have had an indirect bearing upon how the patient experienced receiving the diagnosis from the urologist. Even with the best intentions to communicate the diagnosis in a merciful and empathic way, the combination of the modern, often fast-paced clinic and the seriousness of the disease, inferred from the urologist’s, for example, choice of words, facial expression, and tone of voice may, in turn, have affected the experience when receiving the diagnosis and thus indirectly one’s psychological well-being over time. Results from separate analyses on patients on active surveillance did not change our interpretation of the main findings (results not shown in table).

Strengths of this study include the large sample size of patients along with a high participation rate, prospectively measured on four occasions over the course of two years, enabling us to compare psychological well-being at different time points. Also, the rich data from detailed questionnaires filled out by the patients at home and returned not to the attending urologist but to a trial secretariat, enabled investigating the specific experience of self-assessed emotional shock and probably minimized the risk of measurement errors and avoided any interviewer-related bias.

There are limitations to our study, however. The main study limitation is that we do not have any information on how the diagnosis was delivered (e.g., in person or by telephone) and this may have differed between clinics and even between attending urologists. Some of the clinics may have been subject to more stress and some may have had active routines in place to buffer against self-assessed emotional shock when communicating the diagnosis. However, even if the diagnosis itself is not possible to change, the patient's experience when receiving it may be altered as it may depend on how the diagnosis is communicated. Second, prior exposure to cancer of others in one’s family and among friends prior to receiving the prostate cancer diagnosis may potentially be associated with psychological well-being. Third, the study lacks a standardized tool for evaluating self-assessed emotional shock. Possibly, by using one question, we may have increased the noise compared to if we would have used two questions. In this case, however, an increase in noise is expected to yield conservative associations and thus reduced possibilities to find statistically significant associations. An increase in noise never explains the outcome of statistically significant associations. Following extensive preparation of the questionnaires [Citation12,Citation18], involving several revisions after patient and expert reviews, we believe the chances were maximized that the participants understood the questions the way we had intended. Moreover, if the measurements of self-assessed emotional shock and psychological well-being would have both measured an identical underlying construct, the same individuals who responded ‘high’ on self-assessed emotional shock would have also responded ‘high’ on psychological well-being (the same for those who responded ‘low’ on self-assessed emotional shock and psychological well-being). Indeed, cross tables with self-assessed emotional shock and psychological well-being (at all time points) clearly show that not the same individuals who responded ‘high’ to self-assessed emotional shock also responded ‘high’ to psychological well-being (and the same for those who responded ‘low’ to these questions).

The focus of the study was to report the association between self-assessed emotional shock and psychological well-being and it is possible that other, unknown factors may affect psychological well-being that we have not been able to account for. However, when adjusting for factors that are known to or possibly related to psychological well-being, the association, although attenuated, remained statistically significant. Finally, we were unable to exclude that prediagnostic characteristics such as anxiety or low psychological well-being prior to diagnosis played a role in how a person experienced receiving the diagnosis. It is also possible that aspects of personality characteristics, such as neuroticism, could be related to psychological well-being. Unfortunately, however, this information was not obtained in the LAPPRO study but may well be an area of particular interest in a future study of this patient population.

Despite these limitations, our findings identify self-assessed emotional shock at diagnosis as one of the salient factors contributing to patients’ psychological well-being for up to two years after surgery. To our knowledge, the LAPPRO study is the first larger prospective setting to investigate the reported experiences of self-assessed emotional shock already before surgery. Our findings suggest that it may be of clinical importance to not only prioritize the development of effective interventions that help patients mobilize support from their social network but also to, closely after diagnosis, as well as later down the timeline, follow-up the patients’ reactions and proactively provide psychosocial treatment resources.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this article.

References

- Wall DP, Kristjanson LJ, Fisher C, et al. Responding to a diagnosis of localized prostate cancer: men's experiences of normal distress during the first 3 postdiagnostic months. Cancer Nurs. 2013;36:E44–E50.

- Hsiao CP, Loescher LJ, Moore IM. Symptoms and symptom distress in localized prostate cancer. Cancer Nurs. 2007;30:E19–E32.

- Lehto US, Helander S, Taari K, et al. Patient experiences at diagnosis and psychological well-being in prostate cancer: a Finnish national survey. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2015;19:220–229.

- Allen JG, Coping with trauma: a guide to self-understanding. Arlington, VA, USA: Americal Psychistric Association; 1995.

- Watts S, Leydon G, Eyles C, et al. A quantitative analysis of the prevalence of clinical depression and anxiety in patients with prostate cancer undergoing active surveillance. BMJ Open 2015;5:e006674.

- Taoka R, Matsunaga H, Kubo T, et al. Impact of trait anxiety on psychological well-being in men with prostate cancer. Int Braz J Urol. 2014;40:620–626.

- Huntley A. Prostate cancer: online support reduces distress in men with prostate cancer. Nat Rev Urol. 2016;13:9–10.

- Haglind E, Carlsson S, Stranne J, et al. Urinary incontinence and erectile dysfunction after robotic versus open radical prostatectomy: a prospective, controlled, nonrandomised trial. Eur Urol. 2015;68:216–225.

- Omerov P, Steineck G, Runeson B, et al. Preparatory studies to a population-based survey of suicide-bereaved parents in Sweden. Crisis. 2013;34:200–210.

- Bowling A. Just one question: if one question works, why ask several? J Epidemiol Community Health. 2005;59:342–345.

- Steineck G, Helgesen F, Adolfsson J, et al. Quality of life after radical prostatectomy or watchful waiting. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:790–796.

- Thorsteinsdottir T, Stranne J, Carlsson S, et al. LAPPRO: a prospective multicentre comparative study of robot-assisted laparoscopic and retropubic radical prostatectomy for prostate cancer. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 2011;45:102–112.

- Anderson J, Burney S, Brooker JE, et al. Anxiety in the management of localised prostate cancer by active surveillance. BJU Int. 2014;11:55–61.

- Beck AM, Robinson JW, Carlson LE. Sexual intimacy in heterosexual couples after prostate cancer treatment: what we know and what we still need to learn. Urol Oncol. 2009;27:137–143.

- Helgeson VS, Lepore SJ, Eton DT. Moderators of the benefits of psychoeducational interventions for men with prostate cancer. Health Psychol. 2006;25:348–354.

- Bellardita L, Valdagni R, van den Bergh R, et al. How does active surveillance for prostate cancer affect quality of life? A systematic review. Eur Urol. 2015;67:637–645.

- Stinesen Kollberg KM, Wilderäng U, Thorsteinsdottir T, et al. Psychological well-being and private and professional psychosocial support after prostate cancer surgery: a follow-up at 3, 12, and 24 months after surgery. Eur Urol Focus 2016;2:418–425.

- Zhang L, Gallagher R, Lowres N, et al. Using the ‘think aloud’ technique to explore quality of life issues during standard quality-of-life questionnaires in patients with atrial fibrillation. Heart Lung Circ. 2017;26:150–156.