Abstract

Background: Depression and anxiety are associated with decreased health-related quality of life (HRQoL). The knowledge about the development of anxiety, depression and HRQoL in cancer patients without depression or anxiety, that is initially scoring as non-cases (cutoff <8) according to the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), is sparse. The objectives were: (1) to evaluate changes in anxiety, depression and HRQoL over 6 months in two independent cohorts of oncology patients initially scoring as non-cases by the HADS, (2) to compare stable non-case patients with the general population regarding HRQoL and (3) to explore the outcomes using >4 rather than >7 as cutoff on any of HADS subscales.

Methods: The study group (SG) included 245 and the validation group (VG), a previous cohort, included 281 non-cases. Patients who were non-cases (HADS <8) at all completed assessments were categorized as stable non-cases (stable-NC); those who were doubtful/clinical cases (HADS >7) in at least one follow-up were categorized as unstable-NC. Questionnaires were completed at baseline, and after 1, 3 and 6 months. Age- and sex-matched EORTC QLQ-C30 data from the general population were used for HRQoL comparisons.

Results: One hundred ninety-six (80%) SG and 244 (87%) VG patients were stable-NC and 49 (20%) SG and 37 (13%) VG patients were unstable-NC. SG and VG were similar in all outcomes. Anxiety, depression and HRQoL deteriorated over 6 months for unstable-NC (p < .05). HRQoL for stable-NC was comparable to that in the general population. If >4 had been used as cutoff, most unstable-NC (36/49 and 25/37, respectively) would have been identified at baseline.

Conclusions: Most non-cases are stable-NC with a high stable HRQoL, indicating no need for re-assessment. A minority develop anxiety or depression symptoms and impaired HRQoL; for these a cutoff >4 rather than >7 on HADS subscales may be useful for early detection.

Background

Cancer and its treatments influence psychological well-being and health-related quality of life (HRQoL). Depression and anxiety are associated with decreased HRQoL, and depression is associated with poorer treatment adherence and prognosis [Citation1]. Depressive symptoms are risk factors for all-cause mortality 1–10 years post-diagnosis in cancer survivors [Citation2]. Anxiety and depression have strong and independent association with mental health problems and somatic symptom burden, where depression also has a broad association with several other aspects of HRQoL in cancer patients [Citation3]. Thus, identification of patients with a risk for persistent anxiety and depression symptoms is important. A clinically relevant number of patients has or develops anxiety and depression symptoms with decreased HRQoL.

In longitudinal studies, these problems decrease over time in many patients, whereas for others the problems persist or arises [Citation4]. In patients with various cancer diagnoses, about one-third of the patients with clinically elevated symptoms at baseline experience problems at 12 months [Citation5]. A study of colorectal cancer patients showed a generally low need for psychological support, while a minority reported high persistent unmet needs 12 months post-surgery [Citation6]. Nordin et al. [Citation7] showed that symptoms and clinical cases of anxiety or depression in connection with the diagnosis are predictors of similar status at 6 months. In our previous study of a heterogeneous sample of oncology patients about one of three had symptoms of anxiety and/or depression according to the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), at their first visit to an oncology department. The symptoms decreased but were still frequent at 6 months. HRQoL, initially affected with impaired global health status, role- and emotional functioning and increased symptoms, especially fatigue and insomnia, also improved over time but was still affected 6 months later [Citation8]. However, many patients do not develop persistent anxiety or depression symptoms and express no need for support in addition to adequate information and support from regular health care staff, family and friends [Citation9]. An important aspect of oncology care is to develop methods to identify patients with a low need for additional support to be able to direct available resources to those at risk for persistent psychological distress.

In oncology settings, the HADS is one of the most commonly used self-assessments for anxiety and depression. A meta-analysis suggests lower cutoff scores in cancer patients than recommended in other medically ill patients (>7) [Citation10]. Singer et al. [Citation11], for example, recommend the HADS cutoffs >1 for depression and >2 for anxiety to achieve high sensitivity when used in cancer patients in acute clinical practice. In a previous study, we compared a lower than recommended cutoff on the anxiety and depression scales with a thorough clinical assessment conducted by an oncology nurse or a social worker. The overall agreement between the HADS and the clinical assessment was moderate, where fewer patients with symptoms of anxiety were detected by the HADS than by the clinical assessment. The HADS cutoff >4 for anxiety and depression was suggested most optimal and comparable to the clinical assessment [Citation12]. There is a need to explore how the HADS is best used in different oncology settings and what thresholds may be appropriate for identifying clinically significant psychological morbidity in cancer populations [Citation13]. Little is known about the stability and changes of anxiety, and depression among patients with initially <8 on both HADS subscales (non-cases) and how HRQoL is affected in those who develop such symptoms later in the disease trajectory. More knowledge may facilitate the identification of patients who need repeated assessments and follow-up evaluations and those who are likely to remain free of anxiety and depression symptoms.

Aims

Aims included evaluation of anxiety, depression and HRQoL over 6 months in two independent cohorts of oncology patients scoring as non-cases according to HADS at the initial assessment. For comparison, the changes in patients who scored initially as cases are also presented. A second aim was to compare HRQoL for stable non-cases (stable-NC) patients with normative data from two Swedish population-based studies. A third aim was to explore if a cutoff >4 rather than >7 on HADS anxiety or depression scales at the initial assessment identifies initial non-cases who develop symptoms over 6 months.

Methods

Design

This study has a longitudinal, comparative design including data from two independent cohorts, collected a decade apart, to evaluate if changes in anxiety and depression in a more recent cohort of patients (study group, SG) could be replicated in an earlier also prospectively collected cohort (validation group, VG) and thus strengthen the validity of the findings in the SG. Also, EORTC QLQ-C30 data are compared to normative EORTC QLQ-C30 data from two Swedish population-based studies to explore whether HADS non-cases differ from the general population.

Patients and settings

Study group

Between September 2005 and June 2006, patients were invited to participate within 1 month from their first visit at the Department of Oncology. Patients were invited consecutively, regardless of diagnosis, stage or time since diagnosis (78% were diagnosed <3 months from the first visit). They were informed by a research nurse at the hospital in connection with their first visit or by telephone. After the informed consent form was signed, the questionnaires were distributed to the patients by the research nurse or sent by post together with an addressed prepaid envelope. Exclusion criteria were inability to speak and understand Swedish, cognitive impairment or constant need of hospital care (Karnofsky <40). The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Board, Uppsala University (Reg. no. 2004-Ö-436).

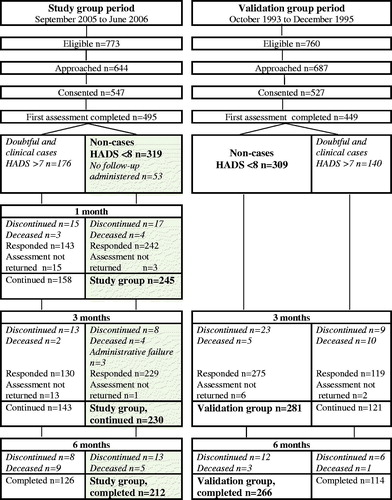

Out of 644 approached patients, 547 (85%) patients gave written informed consent prior to participation. Four hundred and ninety-five patients completed the initial assessment, of whom 319 (64%) patients were non-cases and 176 (36%) patients were doubtful cases or clinical cases according to the HADS (). The patients completed the questionnaires again (see below) after 1, 3 and 6 months. Fifty-three patients were lost to follow-up because non-cases were not included in the follow-up assessments at the beginning of the project. The study protocol was modified in November 2005 with follow-up assessments for all patients.

Figure 1. Participant flow, SG and VG. Discontinued includes patients who actively discontinued participation and patients who stopped returning questionnaires.

In this report, the SG constituted all patients who scored as non-cases according to HADS at the initial assessment and completed at least one follow-up (n = 245). Thirty-three (13%) of them did not complete the entire 6-month follow-up due to discontinued participation (n = 21), death (n = 9) or administrative failure (n = 3). Thus, 212 (87%) of 245 patients completed the study (). Patients who initially were doubtful cases and clinical cases for anxiety and depression according to HADS have been described in a previous report [Citation8], but those results were also included here for contrasting purposes ().

Validation group

The VG consisted of patients with newly diagnosed (<3 months) breast, prostate, colorectal or gastric cancer, consecutively included in a randomized controlled trial between September 1993 and December 1995, that is during a time period with less intensive oncological treatments and more inpatient care compared to the period when patients in the SG were included. The aim of the randomized study was to evaluate the effects of individual support and/or group rehabilitation on anxiety, depression and HRQoL. There were no significant effects of the intervention compared to standard care [Citation14]. Thus, we used the data for all patients from the initial assessment and the 3- and 6-month follow-up as a VG to the present SG. A total of 281 patients, non-cases according to HADS at the initial assessment and who completed at least one follow-up, constituted the VG. Two hundred and sixty-six (93%) of them completed the 6-month assessment (). Fifteen (5%) patients did not complete the entire 6-month follow-up due to discontinued participation (n = 12) or death (n = 3). The results of the 140 patients who were doubtful cases or clinical cases according to HADS at the initial assessment were again included for contrasting purposes ().

Data collection

Demographic and medical background data were collected from medical records.

Anxiety and depression

The HADS was used for assessments of anxiety and depression symptoms. It consists of 14 questions, 7 measuring anxiety and 7 depression. The score for each scale is summarized with a maximum of 21 points. The recommended cutoff for each subscale are <8 categorized as non-cases, >7 as doubtful cases and >10 as clinical cases [Citation15]. For the purpose of this study, patients who were non-cases on both subscales at all completed assessments were categorized as stable-NC. Patients who were non-cases on both subscales at baseline and developed doubtful or clinical cases of anxiety or/and depression at one or more follow-up assessments were categorized as unstable non-cases (unstable-NC); that is unstable anxiety case, unstable depression case or unstable combined anxiety and depression case.

Furthermore, the number of stable-NC and unstable-NC using a score >4 on any of the HADS subscales was separately explored since this cutoff was suggested in an earlier study where we compared HADS with a clinical assessment [Citation12].

Health-related quality of life

EORTC QLQ-C30 includes five functional scales, nine symptom scales and a global quality-of-life (QOL) scale. All questionnaire responses were transformed into scores on a linear 0–100 graded scale according to the EORTC scoring manual [Citation16]. For functional scales and global QOL, a higher score means better level of functioning, while for the symptom scales, a higher score means more problems [Citation17].

Normative data for EORTC QLQ-C30

EORTC QLQ-C30 data for stable-NC in the SG were compared to normative EORTC QLQ-C30 data from a sample of Swedish adults in the general-population from 2008 (n = 4910) [Citation18]. EORTC QLQ-C30 data for stable-NC in the VG were compared to similar data from another sample of Swedish adults in the general-population from 1997 (n = 3069) [Citation19]. Comparisons with normative data were adjusted for age and sex.

Data analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS, version 22 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Demographic and medical background data and data from the HADS and the EORTC QLQ-C30 were analyzed using descriptive statistics. Data from all patients who had completed at least one assessment were used. For EORTC QLQ-C30, missing values were replaced with the mean of each patient’s responses, provided that at least half of the subscale items had been completed [Citation16]. The Mann–Whitney test and the Chi-square test were used to analyze differences between patients completing and patients not completing the study in the SG and the VG, respectively. The Mann–Whitney test was also used to analyze differences between stable-NC and unstable-NC at baseline. The Friedman test was used to analyze differences between baseline, 1, 3 and 6 months with regard to anxiety, depression and HRQoL in unstable-NC. In order to diminish the differences between the SG and VG with regard to time since diagnosis, the sub-set of the patients diagnosed <3 months prior to the first visit was also analyzed. A p value of <.05 was regarded as statistically significant. Differences in the EORTC QLQ-C30 scores were also interpreted in terms of clinically relevant mean changes as small (5–10 points), moderate (11–19 points) or large (≥20 points) [Citation20]. Expected mean scores for the normative patient groups were calculated from the aged and sex adjusted reference values [Citation21].

Results

Attrition analyses

Patients in the SG not completing the study (n = 33) were similar to patients completing the study (n = 212) with regard to age, sex, treatment, advanced/non-advanced cancer, anxiety, depression and most HRQoL domains. However, those who did not complete the study had more dyspnea (p = .014), appetite loss (p < .001) and diarrhea (p = .032) compared to patients completing the study. Also, there were statistically significantly differences with regard to diagnosis (p = .002) where prostate cancer were less represented among patients not completing compared to patients completing the study (6% vs 36%). Patients in the VG who discontinued participation or died (n = 15) had more gastric cancer, less prostate cancer (p < .001) and more advanced disease (p = .010) compared to patients completing the study.

Clinical and demographic characteristics

Half of the 245 patients in the SG were men and the most common diagnoses were prostate cancer, followed by breast and GI-cancer. Most patients were newly diagnosed, had non-advanced cancer, ongoing oncological treatment, usually radiotherapy, and the majority were disease-free at 6 months. The VG patients were similar to the SG concerning age, sex and diagnoses ().

Table 1. Clinical and demographic characteristics of patients initially scoring as non-cases by HADS in the SG and the VG, stable-NC and unstable-NC, n (%).

Development of anxiety and depression symptoms

During the 6 months of follow-up, 196 (80%) of 245 patients in the SG were non-cases at all completed assessments, constituting the stable-NC (). Forty-nine (20%) of the 245 patients who were initially non-cases became unstable anxiety cases (n = 15), unstable depression cases (n = 13) or combined anxiety and depression cases (n = 21) in at least one occasion, constituting the unstable-NC. About half (53%) of the 49 patients scoring above cutoff during follow-ups were doubtful or clinical cases at only one of them, and one-third (33%) at all follow-ups. Stable-NC and unstable-NC were similar concerning demographic and medical background (), whereas unstable-NC had higher baseline mean values for anxiety (5.0 vs 2.8; p = .000) and depression (3.9 vs 2.2; p = .000). In addition, mean anxiety and depression scores for stable-NC were 2.0 at all follow-up assessments compared to increasing mean anxiety (5.0–7.0; p = .001) and depression (3.9–6.5; p = .012) scores in unstable-NC. The development of anxiety and depression in the VG was similar to the SG ().

Table 2. Number (percent) of patients in the SG and VG who scored as non-cases at baseline (HADS 0–7 on both subscales) and remained below 8 (stable-NC) or scored above 7 (unstable-NC) at one or several occasions during 6 months of follow-up according to baseline score (0–4 or 5–7).

HRQoL

In the SG, there were statistically significant mean differences between stable-NC and unstable-NC at baseline regarding global QoL, all functional scales and most symptoms (). For stable-NC, mean global QoL and mean values for all functional scales were high at baseline and stable during the 6-month follow-up. The symptom scales remained stable at comparable low levels. For unstable-NC, most HRQoL dimensions deteriorated over the 6-month follow-up. The mean change for fatigue from baseline (mean 35) to 3 months (mean 56) was interpreted as a large clinically meaningful difference (≥20 points; p = .015). The results were very similar in the VG (). Restricting the comparisons of development of HADS and EORTC scores to those diagnosed <3 months prior to their first visit, constituting most of the patients (), did not change the results (data not shown).

Table 3. Mean values for the EORTC QLQ-C30 for the SG and the VG at all assessments, stable-NC and unstable-NC.

HRQoL for stable-NC compared to the general population

HRQoL in the SG were comparable to the general population at baseline and during the entire follow-up. Only small differences in mean values of worse role functioning and more appetite loss and fatigue were seen, whereas the mean values for pain were higher in the general population compared to the SG. Most HRQoL scales means in the VG were also comparable to the means in the general population ().

Exploration of using >4 as a cutoff for anxiety and depression symptoms

If >4 had been used as the cutoff on HADS subscales 96 (39%) of 245 SG patients would had been identified as having symptoms of anxiety or depression at the initial assessment. The majority (91%) of the patients scoring between 0 and 4 remained stable-NC, whereas 38% (n = 36) of those scoring between 5 and 7 became unstable-NC. The results were very similar in the VG ().

Discussion

The majority, or four out of five patients defined as having no initial symptoms of anxiety and depression at diagnosis remained symptom-free during the subsequent 6 months. These patients had a HRQoL similar to age- and sex-matched population controls. However, about one of five patients developed symptoms of anxiety and depression; these patients had a poorer HRQoL at baseline that also deteriorated during the time period. Anxiety and depression increased in the latter unstable-NC group during follow-up; at 6 months, this unstable-NC group was more similar to the contrasting group of initial cases on HADS whose mean anxiety and depression scores improved during follow-up () [Citation8]. If a lower than usual cutoff had been used on the HADS (4 rather than 7), slightly more than half (51% and 65%) of these patients would have been identified at baseline. Thus, the group that remained free from anxiety and/or depression could be even more safely identified, of potential relevance when designing follow-up programs. The results also appear robust in that they were identical in two independent populations collected a decade apart with very much different intensity in treatments.

Our study is unique in that it explores the fate of a group of patients that has been little explored, since most studies focus on individuals who have some sort of problems. In a group of general oncology patients who consented to participate in a follow-up study exploring the well-being of patients, more than half of them did not express any problems with anxiety or depression during the first 6 months. Since they also had a HRQoL similar to the general population, it may not be necessary to offer them supportive care activities, referral or treatment. However, this should be undertaken with care because it is possible for patients to have unmet psychological needs without high endorsement on anxiety or depression scales. It is a matter of decisions and priorities to judge the benefit and cost consequences in lowering the cutoff scores. Singer et al. invented the term ‘clinical score’ defined as being a point at which at least 95% of cases are identified to minimize the risk of patients with problems going under-recognized and recommended >1 for depression and >2 for anxiety for clinical purposes [Citation11]. We did not have the intention to find an optimal score on HADS for identifying patients who safely can be left without further controls of their levels of anxiety or depression, but scores >4 on both anxiety and depression appeared adequate; to properly identify an ‘optimal’ score for this purpose requires much more rigorous testing. Inaccurate screening, that may lead to incorrect treatment after false positive screens, will cost health care resources, although previous studies have shown that less than half of patients with elevated clinical distress are willing to take advantage of available support services [Citation8,Citation22,Citation23]. Further work needs to be done to develop clinically relevant strategies to secure that appropriate services are provided to patients with the greatest needs.

Already at baseline, there were significant differences in HRQoL between stable and unstable-NC despite all having a HADS score <7. Even low levels of anxiety and depression symptoms, according to HADS seem to affect HRQoL. The unstable-NC scored poorer functioning and more symptoms on most scales compared to stable-NC, although most of them only had anxiety or depression symptoms at one follow-up assessment. A recent large study of 4021 cancer patients showed that comorbid depressive symptoms are associated with both psychological and physical domains of HRQoL in heterogeneous cancer patients. The question whether reduced HRQoL is a consequence of the severity of the patient’s disease or rather of the patient’s psychological status after having received a cancer diagnosis is still unclear [Citation24].

The results in the SG and the VG were similar in all outcomes, although there was a decade between the two studies and slight differences regarding diagnostic groups and time for inclusion. However, most patients were recently diagnosed (<3 months) in the SG, and restricting the analyses to those patients did not change the results. Also, patients in the SG were receiving oncological treatment to a greater extent than those in the VG, which is likely a consequence of the development in oncological treatments over these 10 years. More intensive oncologic treatments have been introduced, and the care is more and more transferred from inpatient to outpatient clinics. This has been made possible due to improved management of commonly severe side effects like nausea and vomiting. However, the newer and more intensive treatments have increased other side effects like fatigue, which is also associated with increased mental distress. Thus, the rapid changes in cancer care did not result in differences in the experiences of mental distress or HRQoL. Most cancer patients do not develop anxiety or depression [Citation25,Citation26], as clearly shown in this study during both time periods, and most patients with emotional distress seem to have resources to manage their problems without need for professional support. Thus, the present results support the benefit of screening, to prevent inappropriate or excessive psychosocial interventions in patients not in need of this resource and thereby concentrating available resources to patients at risk for persistent distress [Citation5,Citation27].

The use of screening tools in clinical care needs to include face-to-face follow-up after the assessments, since the completion of scales complemented with feedback to the patient is associated with positive effects on emotional well-being, which is not the case with completion of scales only [Citation28]. Our results indicate that one important aspect of the face-to-face follow-up after the completion of screening for distress may be to inform many patients about a low risk for development of severe mental distress with an accompanying decrease in HRQoL. Thus, one important use of HADS may be to rule-out non-case patients rather than to identify cases of anxiety, depression or distress, a notion supported by a meta-analysis regarding the diagnostic validity of HADS [Citation30].

Methodological considerations

The VG gave us the opportunity to investigate if the results in the SG could be replicated in another group of oncology patients and thus increase the validity of the results. This was especially interesting as only a minority of patients in the SG changed from non-cases during follow-up, and similar results were found in the VG. We used normative data on the general population from two different studies to adjust to the time periods when the two study cohorts were conducted. However, comparable normative data for the youngest and the oldest patients were lacking. The normative data contained individuals up to 79 years of age, where the oldest age group reported the lowest levels on physical and role functioning and higher levels of pain and fatigue [Citation19]. The comparison to normative data may also contain some methodological difficulties, as EORTC QLQ-C30 was developed for cancer patients and not for use in general populations. However, it has been used in several large population-based studies with similar results [Citation18,Citation19] which serves as valuable references to cancer population studies.

Patients not completing the study were very similar to patients completing the study. Regarding demographic and clinical variables (except for diagnosis where prostate cancer were less represented among patients not completing compared to completers), there were no differences between the two groups. The completion rate was high, or 86% (SG) and 95% (VG). This may indicate a satisfactory generalizability of the findings to groups with somewhat better well-being than that in the entire cancer population.

A limitation is the lack of control concerning previous psychiatric health, disease development and medical treatment outcomes for the patients. Future studies are warranted to explore the clinical impact on the development of anxiety, depression and HRQoL longitudinally in non-case patients. Also, socio-economic factors such as education and income may be of importance for anxiety and depression. Lack of social support is a risk factor for anxiety and depression [Citation7]. We were not able to explore social support in the current study. Thus, there are aspects beyond medical variables that need to be explored regarding their impact on the development of psychological distress in patients without initial problems. Prior to the use of a lower than usual cutoff for HADS (>4 rather than >7) further validation is needed using analyses of accuracy (applying ROC-curves, negative and positive predictive values, sensitivity and specificity) and comparisons with standardized clinical interviews.

Clinical implications

Screening with HADS may be a way of securing resources to patients most in need for support to ease and treat anxiety and depressive symptoms and to handle problems with a decreased functioning and increased symptoms such as fatigue and insomnia. Clinicians should use the face-to-face follow-up with the patients to communicate and inform about the stable emotional and HRQoL status for most non-cases. Clinicians should also be aware of the minority of patients with risk to develop symptoms of anxiety and depression with impaired HRQoL during the course of the disease. Re-assessment and information about support services should be provided for these patients.

Conclusions

Most oncology patients categorized as non-cases according to HADS remain stable-NC during a 6-month follow-up with a HRQoL, comparable to that of the general population, indicating no need of re-assessment. However, about one in five patients are unstable-NC with a poorer and deteriorating HRQoL. Because all results were virtually identical in two independent cohorts collected a decade apart, they appear robust. HADS cutoff >4 may be a useful strategy to identify these patients prior to development of symptoms and repeated assessments can be indicated for these patients.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the patients and staff who participated in this study.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The granting institutions had no roles in the design of the trial, data collection, analysis, interpretation or writing of the manuscript.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Arrieta O, Angulo LP, Nunez-Valencia C, et al. Association of depression and anxiety on quality of life, treatment adherence, and prognosis in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:1941–1948.

- Mols F, Husson O, Roukema JA, et al. Depressive symptoms are a risk factor for all-cause mortality: results from a prospective population-based study among 3,080 cancer survivors from the PROFILES registry. J Cancer Surv. 2013;7:484–492.

- Brown LF, Kroenke K, Theobald DE, et al. The association of depression and anxiety with health-related quality of life in cancer patients with depression and/or pain. Psychooncology. 2010;19:734–741.

- Alfonsson S, Olsson E, Hursti T, et al. Socio-demographic and clinical variables associated with psychological distress 1 and 3 years after breast cancer diagnosis. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24:4017–4023.

- Carlson LE, Waller A, Groff SL, et al. What goes up does not always come down: patterns of distress, physical and psychosocial morbidity in people with cancer over a one year period. Psychooncology. 2013;22:168–176.

- Lam WW, Law WL, Poon JT, et al. A longitudinal study of supportive care needs among Chinese patients awaiting colorectal cancer surgery. Psychooncology. 2016;25:496–505.

- Nordin K, Berglund G, Glimelius B, et al. Predicting anxiety and depression among cancer patients: a clinical model. Eur J Cancer. 2001;37:376–384.

- Thalen-Lindstrom A, Larsson G, Glimelius B, et al. Anxiety and depression in oncology patients; a longitudinal study of a screening, assessment and psychosocial support intervention. Acta Oncol. 2013;52:118–127.

- Carlson LE, Angen M, Cullum J, et al. High levels of untreated distress and fatigue in cancer patients. Br J Cancer. 2004;90:2297–2304.

- Vodermaier A, Millman RD. Accuracy of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale as a screening tool in cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Support Care Cancer. 2011;19:1899–1908.

- Singer S, Kuhnt S, Gotze H, et al. Hospital anxiety and depression scale cutoff scores for cancer patients in acute care. Br J Cancer. 2009;100:908–912.

- Thalen-Lindstrom AM, Glimelius BG, Johansson BB. Identification of distress in oncology patients: a comparison of the hospital anxiety and depression scale and a thorough clinical assessment. Cancer Nurs. 2016;39:E31–E39.

- Carey M, Noble N, Sanson-Fisher R, et al. Identifying psychological morbidity among people with cancer using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale: time to revisit first principles? Psycho-oncology. 2012;21:229–238.

- Johansson B, Brandberg Y, Hellbom M, et al. Health-related quality of life and distress in cancer patients: results from a large randomised study. Br J Cancer. 2008;99:1975–1983.

- Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361–370.

- Fayers P, Aaronson N, Bjordal K, et al. The EORTC QLQ-C30 scoring manual. 3rd ed. Brussels: European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer; 2001.

- Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:365–376.

- Derogar M, van der Schaaf M, Lagergren P. Reference values for the EORTC QLQ-C30 quality of life questionnaire in a random sample of the Swedish population. Acta Oncol. 2012;51:10–16.

- Michelson H, Bolund C, Nilsson B, et al. Health-related quality of life measured by the EORTC QLQ-C30 – reference values from a large sample of Swedish population. Acta Oncol. 2000;39:477–484.

- Osoba D, Rodrigues G, Myles J, et al. Interpreting the significance of changes in health-related quality-of-life scores. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:139–144.

- Hjermstad MJ, Fayers PM, Bjordal K, et al. Using reference data on quality of life–the importance of adjusting for age and gender, exemplified by the EORTC QLQ-C30 (+3). Eur J Cancer. 1998;34:1381–1389.

- Baker-Glenn EA, Park B, Granger L, et al. Desire for psychological support in cancer patients with depression or distress: validation of a simple help question. Psycho-Oncology. 2011;20:525–531.

- Shimizu K, Ishibashi Y, Umezawa S, et al. Feasibility and usefulness of the ‘Distress Screening Program in Ambulatory Care’ in clinical oncology practice. Psycho-oncology. 2010;19:718–725.

- Faller H, Brahler E, Harter M, et al. Performance status and depressive symptoms as predictors of quality of life in cancer patients. A structural equation modeling analysis. Psychooncology. 2015;24:1456–1462.

- Mitchell AJ, Chan M, Bhatti H, et al. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and adjustment disorder in oncological, haematological, and palliative-care settings: a meta-analysis of 94 interview-based studies. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:160–174.

- Krebber AM, Buffart LM, Kleijn G, et al. Prevalence of depression in cancer patients: a meta-analysis of diagnostic interviews and self-report instruments. Psychooncology. 2014;23:121–130.

- Carlson LE, Waller A, Mitchell AJ. Screening for distress and unmet needs in patients with cancer: review and recommendations. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1160–1177.

- Velikova G, Booth L, Smith AB, et al. Measuring quality of life in routine oncology practice improves communication and patient well-being: a randomized controlled trial. JCO. 2004;22:714–724.

- Mitchell AJ, Lord K, Slattery J, et al. How feasible is implementation of distress screening by cancer clinicians in routine clinical care? Cancer. 2012;118:6260–6269.

- Mitchell AJ, Meader N, Symonds P. Diagnostic validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) in cancer and palliative settings: a meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2010;126:335–348.