Angiosarcomas are rare, aggressive malignancies of endothelial origin that account for 1 to 4% of all soft tissue sarcomas [Citation1,Citation2]. Though these tumors can occur at any soft tissue site, 60% arise in the skin and superficial soft tissues, most frequently in the head and neck, breast and limbs [Citation3–5]. While most angiosarcomas arise spontaneously, a subset occur secondary to prior treatment, typically from previous radiotherapy with a latency of approximately 5–10 years [Citation6,Citation7]. Since angiosarcoma is the most prevalent post-radiation secondary sarcoma of the breast, radiation-associated angiosarcoma (RAAS) may increase as the number of patients who undergo breast conserving therapy for early-stage breast cancer increases [Citation8].

Unfortunately, prognosis is poor for angiosarcoma, with an overall 5-year survival of 30–40% [Citation5]. Up to 20–40% of patients have disseminated disease at initial presentation, and nearly half of patients initially treated with curative intent for locoregional disease ultimately develop metastatic disease [Citation5,Citation9–13]. Due to its rare nature, there is limited consensus on treatment recommendations for angiosarcoma, with no randomized trials for localized disease and limited prospective studies. Though rarely curative, margin-negative resection remains the preferred choice for patients with localized disease [Citation4,Citation5,Citation9,Citation10,Citation13]. A recent analysis of 821 patients from the National Cancer Database identified poor prognostic factors following surgical resection, including older age, black race, grade 3 histology, larger tumor size and positive margins [Citation4].

Radiation therapy has been shown to improve local control in soft tissue sarcomas, with superior survival in some series when used in the adjuvant setting [Citation14], but has not demonstrated a survival benefit in other series [Citation9,Citation10]. While traditionally anthracycline-based chemotherapy has been used to treat metastatic soft tissue sarcomas, taxanes are now increasingly used and have demonstrated >50% response in several studies [Citation5,Citation13,Citation15,Citation16]. To expand the understanding of this rare soft tissue sarcoma subtype, we retrospectively examined disease course and evaluated factors for improved clinical outcomes in a cohort of primary and secondary angiosarcoma patients at our institution. Outcome metrics included overall survival (OS), progression-free survival (PFS), recurrence, and prognostic factors for recurrence and survival.

Methods

Patient selection and treatment information collected

A retrospective review of patients treated at our institution for angiosarcoma between 2000 and 2015 was conducted with approval of the Institutional Review Board. The following information was reviewed: (1) patient and tumor characteristics, (2) treatment information and (3) recurrence information. Length of follow-up was defined as time from initial diagnosis to date of last follow-up or death.

Outcomes analyzed and statistical analysis

The following outcomes were assessed: OS, defined as the time from pathological diagnosis until the patient’s death; PFS, defined as the time interval from initial treatment until the time of first progression (local recurrence or metastasis) or date of death if no documented progression; time to recurrence; and prognostic factors for survival. Survival was analyzed using Kaplan–Meier analysis with log-rank (Mantel–Cox) test for differences between groups. Multivariate analysis of factors affecting OS was performed using the Cox regression. Multivariate analysis of factors affecting recurrence was performed using multinomial logistic regression. All statistical analysis were performed using SPSS v22 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Patient characteristics and treatment received

The characteristics of this patient cohort are described in . The majority of patients had primary/sporadic sarcomas (75%), while 25% were secondary angiosarcomas that developed at a median of 7.7 years from prior radiation therapy. Of the RAASs, 75% (12/16) were of the breast, chest wall or axilla. The majority of patients presented with localized disease (67% were stage I or II, or non-node-positive stage III). The median follow-up time from date of diagnosis was 15.5 months (range 0.5–171.8 months). Treatment at initial diagnosis included surgery in 79% of patients, chemotherapy in 38%, and radiation therapy in 33%. The number of patients treated with each treatment regimen and sequence is reported in . The majority of patients (60%) had R0 resections. Taxane-based chemotherapy was used to treat 83% of patients, and radiation therapy was given to a median dose of 54 Gy.

Table 1. Patient characteristics and treatment information.

Disease recurrence

Nearly half (46%) of patients developed locoregional or distant recurrences, and half of these patients experienced multiple recurrences. The majority of initial recurrences were locoregional (62%), while 38% were distant. Recurrence developed with similar frequency for sporadic and secondary etiologies. The median time to any recurrence from initial treatment was 9.4 months (range 0.5–122 months). The median time to initial locoregional recurrence was 12.3 months (range 1.8–122 months) and 4.7 months (range 0.5–38.5 months) for initial distant recurrences. On multivariate analysis of factors affecting recurrence, only chemotherapy given as part of initial treatment was associated with reduced overall recurrence (odds ratio [OR] 0.21, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.05–0.89, p = .034).

Survival outcomes

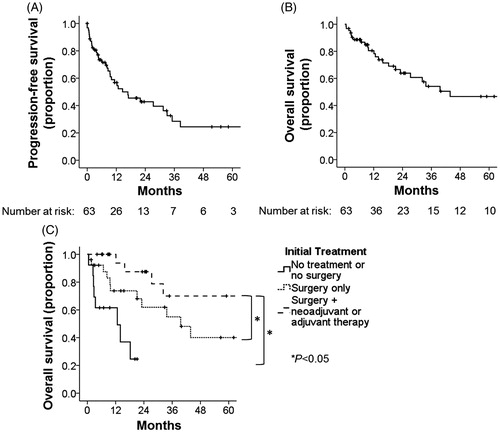

Median PFS from initial treatment was 14.6 months (range 0.0–122.0 months, 95% CI 4.2–25.0 months), and 5-year PFS was 25%. Median OS from initial diagnosis was 43.8 months (range 0.5–171.8 months, 95% CI 10.8–76.8 months), and 5-year OS was 47% (). On univariate analysis (, Supplementary Figure 1, Supplementary Table 1), better OS was seen in patients with breast/chest angiosarcoma (median 89.7 months vs. 39.6 months for head/neck and 12.7 months for extremity, p = .008), those with secondary angiosarcoma (median 81.7 months vs. 32.2 months for primary sarcoma, p = .024), patients with stage I–II disease (median 74.3 months vs. 21.1 months for stage III and 12.7 months for stage IV disease, p = .02), and patients treated with surgery with either adjuvant or neoadjuvant therapy (median 74.3 months vs. 39.6 months for surgery alone and 12.7 months for no surgery or no treatment, p < .001).

Figure 1. (A) Progression-free survival from time of initial treatment (date of surgery if applicable, otherwise end of radiation therapy or end of first course of chemotherapy) via Kaplan–Meier analysis. (B) Overall survival from time of initial diagnosis via Kaplan–Meier analysis. (C) Overall survival from time of initial diagnosis by initial treatment modality via Kaplan–Meier analysis. Statistical significance via log-rank test.

On multivariate analysis (Supplementary Table 2), better OS was still seen in patients treated initially with surgery and either adjuvant or neoadjuvant therapy compared to surgery only (OR 4.8 [95% CI 1.7–13.4], p = .002) or no surgery/no treatment at all (OR 7.6 [95% CI 2.4–24.8], p = .001) and in patients with secondary etiology compared to primary/sporadic etiology (OR 4.6 [95% CI 1.3–16.3], p = .019). Better OS was no longer significantly associated with breast/chest primary site.

Discussion

This single-institution retrospective study represents one of the larger series of patients treated for angiosarcoma of multiple primary sites with current chemotherapy regimens. Our results suggest that while survival remains poor overall and recurrences frequent for angiosarcoma, combined modality therapy that includes surgical resection with taxane-based chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy improves survival over surgical resection alone.

Our results confirm that recurrences are common for patients with angiosarcoma and that patients are at risk for multiple recurrences. Interestingly, patients developed locoregional recurrences at a median of 12 months, compared to distant recurrences at a median of 5 months. These early distant recurrences, along with our results indicating reduced risk of recurrence with chemotherapy, suggest that chemotherapy should not be delayed in management of angiosarcoma.

Importantly, our study demonstrated a significant survival benefit with the use of combined modality therapy (surgery with neoadjuvant or adjuvant therapy) compared to surgery alone. However, no specific survival benefit was seen with the use of chemotherapy or radiotherapy in our series, which could be related to limited use of both modalities in our study (each used in 30–40% of patients as part of initial management). Chemotherapy (but not radiotherapy) was associated with reduced overall recurrence in our study. Previous studies have demonstrated conflicting results regarding the roles of radiotherapy and chemotherapy, with some demonstrating improved local control or survival and others no clear benefit [Citation9,Citation10,Citation14,Citation17]. We note that a majority of patients in our series (83%) were treated with taxane-based chemotherapy regimens, which may potentially have greater benefit in angiosarcoma due to antiangiogenic activity and have demonstrated good response in several series [Citation15,Citation16].

To our knowledge, this study is the first to report superior survival with radiation-associated angiosarcomas compared to primary tumors. A few other studies have reported a trend toward better overall survival in secondary angiosarcomas [Citation10,Citation18,Citation19], but traditionally RAAS has been associated with worse survival and increased recurrence [Citation7,Citation9]. It is possible that better outcomes for RAAS are now being seen in the context of heightened awareness and earlier detection, increased immune response to radiation-induced mutations [Citation20], and better response to chemotherapy than primary angiosarcomas seen in one study [Citation15]. Other studies suggest better local control with surgery followed by re-irradiation for RAAS [Citation6,Citation21].

This study has several limitations inherent to a retrospective study, including differences in treatment regimens selected based on patient factors and practitioner preference. Given the rare nature of angiosarcoma and lack of clear management guidelines, there was no standard combination and sequence of treatments used. Importantly, the small size of our study cohort required grouping all anatomic sites together and prohibited subset analysis. A relatively small proportion of patients received chemotherapy or radiotherapy, precluding in-depth analysis of these treatment modalities. However, compared to several other studies of angiosarcoma, we do report a large cohort from a contemporary period of time that incorporates newer treatment modalities.

In conclusion, angiosarcoma is a rare but aggressive disease with high recurrence rates and poor survival. However, surgery with neoadjuvant or adjuvant therapy has the potential to improve overall survival. Combined modality therapy should be utilized to treat patients with this aggressive malignancy, even for patients who present initially with localized disease. Further investigation is needed into newer systemic agents to improve clinical outcomes.

IONC_1306104_Supplementary_information.zip

Download Zip (165.7 KB)Disclosure statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Mastrangelo G, Coindre JM, Ducimetiere F, et al. Incidence of soft tissue sarcoma and beyond: a population-based prospective study in 3 European regions. Cancer. 2012;118:5339–5348.

- Rouhani P, Fletcher CD, Devesa SS, et al. Cutaneous soft tissue sarcoma incidence patterns in the U.S.: an analysis of 12,114 cases. Cancer. 2008;113:616–627.

- Mendenhall WM, Mendenhall CM, Werning JW, et al. Cutaneous angiosarcoma. Am J Clin Oncol. 2006;29:524–528.

- Sinnamon AJ, Neuwirth MG, McMillan MT, et al. A prognostic model for resectable soft tissue and cutaneous angiosarcoma. J Surg Oncol. 2016;114:557–563.

- Young RJ, Brown NJ, Reed MW, et al. Angiosarcoma. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:983–991.

- Depla AL, Scharloo-Karels CH, de Jong MA, et al. Treatment and prognostic factors of radiation-associated angiosarcoma (RAAS) after primary breast cancer: a systematic review. Eur J Cancer. 2014;50:1779–1788.

- Ghareeb ER, Bhargava R, Vargo JA, et al. Primary and radiation-induced breast angiosarcoma: clinicopathologic predictors of outcomes and the impact of adjuvant radiation therapy. Am J Clin Oncol. 2014;39:463–467.

- Yap J, Chuba PJ, Thomas R, et al. Sarcoma as a second malignancy after treatment for breast cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;52:1231–1237.

- Abraham JA, Hornicek FJ, Kaufman AM, et al. Treatment and outcome of 82 patients with angiosarcoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:1953–1967.

- Buehler D, Rice SR, Moody JS, et al. Angiosarcoma outcomes and prognostic factors: a 25-year single institution experience. Am J Clin Oncol. 2014;37:473–479.

- Espat NJ, Lewis JJ, Woodruff JM, et al. Confirmed angiosarcoma: prognostic factors and outcome in 50 prospectively followed patients. Sarcoma. 2000;4:173–177.

- Fayette J, Martin E, Piperno-Neumann S, et al. Angiosarcomas, a heterogeneous group of sarcomas with specific behavior depending on primary site: a retrospective study of 161 cases. Ann Oncol. 2007;18:2030–2036.

- Fury MG, Antonescu CR, Van Zee KJ, et al. A 14-year retrospective review of angiosarcoma: clinical characteristics, prognostic factors, and treatment outcomes with surgery and chemotherapy. Cancer J. 2005;11:241–247.

- Mark RJ, Poen JC, Tran LM, et al. Angiosarcoma. A report of 67 patients and a review of the literature. Cancer. 1996;77:2400–2406.

- Italiano A, Cioffi A, Penel N, et al. Comparison of doxorubicin and weekly paclitaxel efficacy in metastatic angiosarcomas. Cancer. 2012;118:3330–3336.

- Penel N, Bui BN, Bay JO, et al. Phase II trial of weekly paclitaxel for unresectable angiosarcoma: the ANGIOTAX Study. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:5269–5274.

- Singla S, Papavasiliou P, Powers B, et al. Challenges in the treatment of angiosarcoma: a single institution experience. Am J Surg. 2014;208:254–259.

- Hillenbrand T, Menge F, Hohenberger P, et al. Primary and secondary angiosarcomas: a comparative single-center analysis. Clin Sarcoma Res. 2015;5:14–15.

- Scott MT, Portnow LH, Morris CG, et al. Radiation therapy for angiosarcoma: the 35-year University of Florida experience. Am J Clin Oncol. 2013;36:174–180.

- Behjati S, Gundem G, Wedge DC, et al. Mutational signatures of ionizing radiation in second malignancies. Nat Commun. 2016;7:12605.

- Smith TL, Morris CG, Mendenhall NP. Angiosarcoma after breast-conserving therapy: long-term disease control and late effects with hyperfractionated accelerated re-irradiation (HART). Acta Oncol. 2014;53:235–241.