Abstract

Background: Admittance to specialized palliative care (SPC) has been discussed in the literature, but previous studies examined exclusively those admitted, not those with an assessed need for SPC but not admitted. The aim was to investigate whether admittance to SPC for referred adult patients with cancer was related to sex, age, diagnosis, geographic region or referral unit.

Material and methods: A register-based study with data from the Danish Palliative Care Database (DPD). From DPD we identified all adult patients with cancer, who died in 2010–2012 and who were referred to and assessed to have a need for SPC (N = 21,597).The associations were investigated using logistic regression models, which also evaluated whether time from referral to death influenced the associations.

Results: In the adjusted analysis, we found that admittance was higher for younger patients [e.g., 50–59 versus 80 + years: odds ratio (OR) = 2.03; 1.78–2.33]. There was lower odds of admittance for patients with hematological malignancies and patients from two regions: Capital Region of Denmark and Region of Southern Denmark. Lower admittance among men and patients referred from hospital departments was explained by later referral.

Conclusions: In this first nationwide study of admittance to SPC among patients with a SPC need, we found difference in admittance according to age, diagnosis and region. This indicates that prioritization of the limited resources means that certain subgroups with a documented need have reduced likelihood of admission to SPC.

Introduction

In Denmark, ∼16,000 persons die from cancer every year [Citation1] and as in many other countries it is a public agenda to improve access to palliative care for patients with cancer and other life threatening diseases [Citation2]. Palliative care may be provided everywhere in the health care system, whereas specialized palliative care (SPC) is provided by palliative care teams/units and hospices to patients with complex problems that according to clinical judgment cannot be adequately managed elsewhere [Citation3]. SPC can reduce symptom burden and improve quality of life for patients with cancer and their caregivers, and has been shown to be cost-effective [Citation4–6].

In the literature, lower access to SPC has been reported for men [Citation7–9], older persons [Citation10–17] and in rural areas [Citation8,Citation10,Citation14,Citation15,Citation18–20]. Compared with patients with other diagnoses, patients with cancer had the highest level of access [Citation11,Citation13,Citation14,Citation16,Citation17]. Among patients with cancer the lowest admittance to SPC was found in patients with hematological malignancies [Citation16,Citation17,Citation21,Citation22].

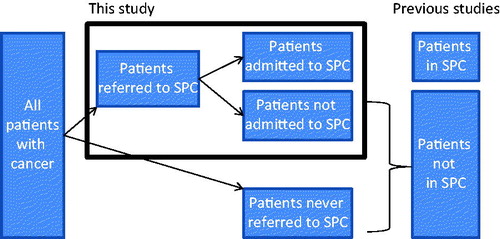

Previous studies have not investigated access to SPC in the entire group of patients referred to SPC. The Danish Palliative Care Database (DPD) registers all referrals to SPC in Denmark, which makes it possible not just to compare patients admitted to SPC with patients who are not admitted, but further to identify the patients who were referred but not admitted to SPC (). In contrast to all previous studies of access, it is therefore unique that this database makes it possible to study admittance to SPC in the entire group of patients viewed by their treating physician (who refers the patient) and the SPC unit (who accepts the patient) as having a need for SPC (‘often defined as complex symptomatology that could not be managed outside SPC’).

Being informed and acknowledging that you are a terminally ill patient who is in need of SPC, and accepting this referral, may be a substantial life event. Not being admitted may be a distressing disappointment, as one may fear that it reduces the likelihood of achieving optimal symptom control and end-of-life care.

The aim of this study was to investigate whether sex, age, cancer diagnosis, geographic region or referral unit were related to admittance to SPC in a national population of adult patients with cancer who were referred to and judged by their physician and SPC unit to have a need for SPC.

Material and methods

The study is a population based study based on existing data in DPD and the Danish Cancer Registry (CR). Each individual living in Denmark has a unique personal registration number, which makes it possible to link data from different data sources.

Setting

Denmark has 5.6 million inhabitants. The number of SPC units (hospital-based palliative care team/unit and hospice) increased from 36 units in 2010 to 44 units in 2012. Admittance to the SPC is, as the majority of other healthcare services, free of charge. The recommendations from EAPC stated that the SPC capacity should be; 80–100 beds per 1 million inhabitants and one home palliative care team for every 100,000 inhabitants [Citation23]. In Denmark there are 48 beds per million inhabitants, half the size recommended and 26 palliative care teams, 30 less than suggested from the EAPC. The capacity problem is seen in all regions, with the best SPC capacity in North Denmark Region ().

Table 1. Comparison of EAPC recommendations with regard to the number of SPC beds and teams versus the number in Denmark (2012).

Table 2. Characteristics of the study population.

Data sources

Since 1 January 2010, it has been mandatory for all SPC units in Denmark to register all referred patients and data concerning these referrals in DPD. To maximize the completeness of the DPD, data were linked with the Danish National Patient Register (DNPR) [Citation24]. Patients registered with a contact to an SPC unit in the DNPR were added to the DPD if the SPC unit confirmed the contact. The data completeness of DPD was high: in 2010–2012 all SPC units registered their patients in DPD (unit completeness: 100%), with annual patient completeness of 96, 99 and 100%, respectively [Citation25]. The DPD was further linked to the Danish Civil Registration System making information regarding date of death available [Citation26].

Information about cancer diagnoses was collected from the Danish Cancer Registry (CR), which is a nationwide research register which contains incident cancer cases since 1943 including data on tumor characteristics [Citation27].

Population

Adult (≥18 years) patients with cancer living in Denmark who were referred to SPC were included if they

were referred after 1 January 2010

died between 1 January 2010 and 31 December 2012 and

were meeting the referral criteria and did not refuse SPC (some patients changed their mind after the referral and did not want SPC) or were unsuitable for treatment (e.g., patients that were too close to death or who could not be accommodated in the unit).

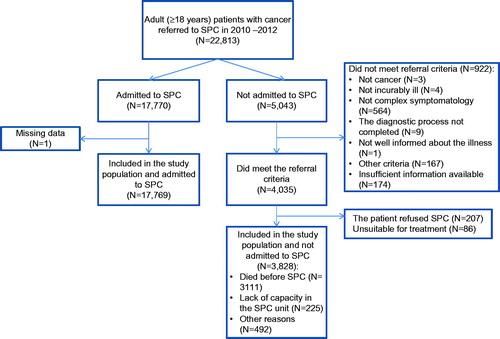

For patients meeting the referral criteria who were not admitted to SPC (n = 3828) the most frequent reason was ‘died before SPC’ (n = 3111). For patients not meeting the referral criteria (n = 922), the most common reason was ‘not complex symptomatology’ (n = 564). For further details see .

Figure 2. Flow chart of the patients referred to SPC in 2010–2012 and included in the study population.

If patients were initially rejected but later admitted to SPC they were considered admitted.

Variables

Descriptive variables: Date of referral to SPC, fulfillment of eligibility criteria as evaluated by the SPC unit and date of death.

Outcome variable: Admittance to SPC, defined as any personal contact with SPC: inpatient, home visit, outpatient SPC or palliative care team visits at non-SPC departments (yes/no).

Explanatory variables: Sex, age at the time of death (18–39, 40–49, 50–59, 60–69, 70–79, 80 + years), and geographic region. Diagnosis, coded using ICD-10 following the Danish Cancer Registry [Citation28] and Bray [Citation29]. Differently from Bray we grouped oral cavity, nasopharynx and other pharynx cancers into one group whereas small intestine cancer and sarcomas, were included as separate groups, not in ‘other’. The referring unit (general practitioner, hospital department, and other). Additionally, in some analyses, number of days from referral to death (<8, 8–21, 22–59 and 60 + days).

The cancer diagnosis from DPD was validated against CR. For most patients (82%) the same diagnosis was found in the two registers. Different cancer diagnoses were found for 16%, these individuals were included in the study with the cancer diagnosis registered in CR. If there was more than one cancer registration, the latest was used. Patients with no cancer registration in CR were included with the cancer diagnosis from DPD (2%).

Data analysis

The associations between the explanatory variables and admittance to SPC were investigated using univariate (‘unadjusted model’) and mutually adjusted logistic regression analysis (including all explanatory variables, ‘adjusted model 1’). The average for all diagnoses was used as reference group for diagnosis. Diagnoses with < 20 patients were included in the group of other cancer diagnoses.

The timing of referral (i.e., time from referral to death) may affect admittance to SPC, and may also be related to some of the variables tested here, e.g., if older patients are referred later. Therefore, number of days from referral to death was included in ‘adjusted model 2’.

The results from the logistic regression models are reported as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Statistical significance was p < .05. All analyses were conducted using SAS statistical software version 9.3 (SAS Inc., Cary, NC, USA) [Citation30].

Results

The study population

From 1 January 2010, 22,813 adult (≥18 years) patients with cancer were referred to SPC and died before 31 December 2012. Excluded from the study were 1216 patients (details in ). Thus, 21,597 patients judged to have a need for SPC were included in the analyses.

Patient characteristics

Half of the patients were men (50.2%), 80.0% were above the age of 60 years, and 1.3% were below 40 years (). The most common diagnoses were lung (24.6%), colorectal (12.0%) and breast cancer (8.2%). The majority of the patients were referred from hospital departments (69.3%) and 19.1% survived <8 days from time of referral.

Admittance to SPC

‘Unadjusted model’. The overall proportion of admittance to SPC was 82.3% (17,769/21,597). No association was found between sex and admittance to SPC. However, the association between all other explanatory variables and admittance to SPC was statistically significant ().

Table 3. Admittance to SPC of Danish cancer patients with an assessed need for SPC in relation to sex, age, region, diagnosis, referral unit and time from referral to death (N = 21,597).

‘Adjusted model 1’. In relation to age, diagnosis and geographic region the results from the ‘Adjusted model 1’ showed only minor differences compared to the unadjusted model (). Younger patients were much more likely to be admitted to SPC compared to older patients. Relatively large differences according to diagnosis were seen. Cancer patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma (0.57; 0.42–0.76) and leukemia (0.55; 0.42–0.73) had the lowest odds of admittance to SPC, whereas the highest significant odds ratio were found for patients with laryngeal cancer (2.56; 1.21–5.39) compared to the average of all diagnoses. Compared to Capital Region of Denmark, patients in North Denmark Region had more than two-fold higher OR (2.26; 1.99–2.57) of admittance to SPC.

Including time from referral to death

The odds of admittance to SPC increased markedly as time from referral to death increased (p < .001). After adjustment for time from referral to death the associations with sex (p = .67) and referral unit (p = .52) became insignificant (‘adjusted model 2’, ): men and patients referred from hospital departments were referred a little later in their trajectory (closer to death) (). Compared with the ‘adjusted model 1’, the model showed a slightly weaker association between admittance to SPC and age and a stronger association for region. The association for several diagnoses changed, suggesting a relationship between diagnosis and timing of referral ().

Table 4. Mean and median time from referral to SPC to death based on sex and referral unit (N = 21,597).

Discussion

Main findings

This study examined admittance to SPC at a national level among patients with cancer who were referred to SPC and had been assessed by their physician and the SPC unit to have a need for SPC. We found that admittance to SPC was lower for older patients, patients living in the Capital Region of Denmark and Region of Southern Denmark and patients having hematological malignancies.

Some of the differences found in this study reflect that some groups of patients were referred later in their disease trajectory than others, i.e., that the difference is caused by late recognition of needs for SPC or that the needs occur later in the trajectory in certain sub-groups. This was the case concerning men and patients referred from hospital departments.

In a health care system with limited resources, a part of the everyday life is to prioritize between the patients referred. This is also the case in relation to SPC. It is fully understandable and a fair utilization of the available resources if those with the most urgent needs are given priority. The difference in need may explain some of the difference found in the present study in relation to e.g., age and diagnosis. The decreasing admittance to SPC with increasing age, may reflect particularly alarming needs in the youngest patients (e.g., problems with children living at home) and thereby a fair difference. As shown in , the capacity of SCP in Denmark is substantially lower than recommended by the EAPC [Citation23]. It is possible that the relatively limited SPC capacity in Denmark have had important consequences for certain subgroups, e.g., older individuals with a need for SPC.

Previous studies have found that even though the symptom burden is similar to other patients groups [Citation31–33] hematological cancers were less represented in SPC than patients with solid tumors [Citation34,Citation35] and have attributed this to; late referral to SPC [Citation17,Citation36–40], prognostic difficulties to indicate appropriateness of palliative care [Citation41–44], lack of knowledge about the role of SPC [Citation41,Citation45–48], and low acceptability of SPC [Citation42,Citation44]. However, it is notable that the present study shows that even when hematological patients were actually referred to SPC, their chances of admission were lower. This suggests that there may be additional explanations. For example, there might be a reluctance in SPC units to receive patients with hematological cancers due to former experience. This should be further investigated.

The development of SPC in Denmark started relatively late compared with other European countries, and during the study period (2010–2012) it was widely recognized that the capacity was insufficient [Citation49,Citation50]. It is likely that the geographic differences found in this study could be explained by the SPC capacity, which was larger in some regions than others (). National laws have enforced the establishing of new hospice beds throughout the country. This has not been the case regulating the establishing of hospital palliative care teams/units (hospitals are run by regional councils), and accordingly, the planning probably has been more diverse and determined by local initiatives, economy, and interests. This may explain some of the differences between the regions and could indicate a need of a national strategy in order to ensure an equal geographical distribution of SPC units regionally.

Comparison with the existing literature

We have not identified any studies investigating the admittance rate for patients referred to and assessed to have a need for SPC. The results of the present study are therefore not directly comparable with previous research. On the other hand our results may help explain previous findings in studies looking at the absolute probability of admittance to SPC (i.e., not among those referred as in our study). Those studies have found the same age gradient, where older patients are less likely to be admitted to SPC [Citation10–17], geographic differences [Citation8,Citation10,Citation14,Citation15,Citation18–20], and less likelihood of admittance for patients with hematological cancer [Citation16,Citation17,Citation21,Citation22].

Thus, our study shows that at least part of the under-representation of certain subgroups found previously can be attributed to reduced likelihood of admittance among referred patients. We found a sex difference with lower admittance for men, whereas most studies (except [Citation7–9]) have found no sex difference. However, the sex difference was explained by time from referral to death, i.e., a lower proportion of men were admitted reflecting that they were referred later.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

As DPD is a national database with very high data completeness and covers the entire Danish population, it minimizes the influence of selection bias. The analyses included a large dataset 21,597 patients with an assessed need for SPC. The study concerns to a period of three years, where there have been no major political or legislative changes that could influence the results, although, a steadily growing number of SPC units across the country were seen during the study period. The validity of the assessment of need of SPC is high, because it was done by clinicians, while the patient was still alive, and the patients included in this study all had needs for SPC according to the referring doctor, according the patients themselves (by consenting to referral) and the target SPC unit. On the other hand, it is a limitation of the study that it has not been possible to classify the specific needs of SPC for the patients. Difference in need may explain part of the difference observed, but this does not change the findings that some groups of patients have lower admittance to SPC.

Admittance was measured as a dichotomous variable, independently of the quantity of SPC. This can be seen as an oversimplification. However, we believe that when the patients are admitted to SPC they do get the care they need, why it makes sense to have only two groups; the main difference being whether patients are admitted or not. It would however be interesting to investigate differences in the type and extent of SPC.

Conclusions

In this first ever nationwide study of patients with cancer assessed to have a need for SPC, we found differences in admittance to SPC in Denmark in relation to age, diagnosis and region. The differences concerning sex and referral unit were explained by later referral; men and patients referred from hospital departments were referred later (closer to death). It is possible and we hope that the results reflect a fair prioritization of the available resources to patients with the most urgent needs. On the other hand even if such prioritization is fair, it means that certain groups of patients having a need for SPC, e.g., the oldest, die without admittance to SPC. The SPC capacity problem in Denmark should therefore be addressed.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the SPC units (hospital palliative care teams/units and hospices) in Denmark for delivering data to DPD, which is funded by the Danish Regions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- The Danish Register of Causes of Death [Internet]. [Dødsårsagsregisteret]; [cited 2017, Apr 18]. Available from: http://sundhedsdatastyrelsen.dk/da/tal-og-analyser/analyser-og-rapporter/andre-analyser-og-rapporter/doedsaarsagsregisteret.

- Danish Health and Medicines Authority. Recommendations for palliative care. [Anbefalinger for den palliative indsats.]; Copenhagen: Danish Health and Medicines Authority; 2011.

- Radbruch L, Payne S. Whitepaper on standards and norms for hospice and palliative care in Europe: part 1. Eur J Palliat Care. 2009;16:278–289.

- El-Jawahri A, Greer JA, Temel JS. Does palliative care improve outcomes for patients with incurable illness? A review of the evidence. J Support Oncol. 2011;9:87–94.

- Higginson IJ, Evans CJ. What is the evidence that palliative care teams improve outcomes for cancer patients and their families? Cancer J. 2010;16:423–435.

- Morrison RS, Penrod JD, Cassel JB, et al. Cost savings associated with US hospital palliative care consultation programs. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:1783–1790.

- Fadul N, Elsayem A, Palmer JL, et al. Predictors of access to palliative care services among patients who died at a comprehensive cancer center. J Palliat Med. 2007;10:1146–1152.

- Lackan NA, Ostir GV, Freeman JL, et al. Decreasing variation in the use of hospice among older adults with breast, colorectal, lung, and prostate cancer. Med Care. 2004;42:116–122.

- Virnig BA, Mcbean AM, Kind S, et al. Hospice use before death - variability across cancer diagnoses. Med Care. 2002;40:73–78.

- Burge FI, Lawson BJ, Johnston GM, et al. A population-based study of age inequalities in access to palliative care among cancer patients. Med Care. 2008;46:1203–1211.

- Ahmed N, Bestall JC, Ahmedzai SH, et al. Systematic review of the problems and issues of accessing specialist palliative care by patients, carers and health and social care professionals. Palliat Med. 2004;18:525–542.

- Burt J, Raine R. The effect of age on referral to and use of specialist palliative care services in adult cancer patients: a systematic review. Age Ageing. 2006;35:469–476.

- Cohen J, Wilson DM, Thurston A, et al. Access to palliative care services in hospital: a matter of being in the right hospital. Hospital charts study in a Canadian city. Palliat Med. 2012;26:89–94.

- Maddison AR, Asada Y, Burge F, et al. Inequalities in end-of-life care for colorectal cancer patients in Nova Scotia, Canada. J Palliat Care. 2012;28:90–96.

- Rosenwax LK, McNamara BA. Who receives specialist palliative care in Western Australia – and who misses out. Palliat Med. 2006;20:439–445.

- Walshe C, Todd C, Caress A, et al. Patterns of access to community palliative care services: a literature review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;37:884–912.

- Hui D, Kim SH, Kwon JH, et al. Access to palliative care among patients treated at a comprehensive cancer center. Oncologist. 2012;17:1574–1580.

- Beccaro M, Costantini M, Merlo DF. Inequity in the provision of and access to palliative care for cancer patients. Results from the Italian survey of the dying of cancer (ISDOC). BMC Public Health. 2007;7:66.

- Hunt RW, Fazekas BS, Luke CG, et al. The coverage of cancer patients by designated palliative services: a population-based study, South Australia, 1999. Palliat Med. 2002;16:403–409.

- Kessler D, Peters TJ, Lee L, et al. Social class and access to specialist palliative care services. Palliat Med. 2005;19:105–110.

- Currow DC, Agar M, Sanderson C, et al. Populations who die without specialist palliative care: does lower uptake equate with unmet need? Palliat Med. 2008;22:43–50.

- Howell DA, Shellens R, Roman E, et al. Haematological malignancy: are patients appropriately referred for specialist palliative and hospice care? A systematic review and meta-analysis of published data. Palliat Med. 2011;25:630–641.

- Radbruch L, Payne S. White Paper on standards and norms for hospice and palliative care in Europe: part 2. Eur J Palliat Care. 2010;17:22–33.

- Lynge E, Sandegaard JL, Rebolj M. The Danish National Patient Register. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39:30–33.

- Hansen MB, Grønvold M. Danish palliative care database annual report 2012. [Dansk Palliativ Database Årsrapport]; Copenhagen: DMCG-PAL; 2012.

- Pedersen CB. The Danish Civil Registration System. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39:22–25.

- Gjerstorff ML. The Danish Cancer Registry. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39:42–45.

- Danish Health and Medicines Authority. The Danish Cancer Registry. Statistic and analysis. [Cancerregisteret 2009. Tal og analyse]; Copenhagen: Danish Health and Medicines Authority; 2009.

- Bray F, Sankila R, Ferlay J, et al. Estimates of cancer incidence and mortality in Europe in 1995. Eur J Cancer. 2002;38:99–166.

- SAS Institute Inc. SAS/STAT 9.3 users’s guide. SAS Institute Inc.: Cary, NC; 2011.

- Johnsen AT, Petersen MA, Pedersen L, et al. Symptoms and problems in a nationally representative sample of advanced cancer patients. Palliat Med. 2009;23:491–501.

- Johnsen AT, Tholstrup D, Petersen MA, et al. Health related quality of life in a nationally representative sample of haematological patients. Eur J Haematol. 2009;83:139–148.

- Manitta V, Zordan R, Cole-Sinclair M, et al. The symptom burden of patients with hematological malignancy: a cross-sectional observational study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011;42:432–442.

- Hui D, Didwaniya N, Vidal M, et al. Quality of end-of-life care in patients with hematologic malignancies: a retrospective cohort study. Cancer. 2014;120:1572.

- Sexauer A, Cheng MJ, Knight L, et al. Patterns of hospice use in patients dying from hematologic malignancies. J Palliat Med. 2014;17:195–199.

- Cheng WW, Willey J, Palmer JL, et al. Interval between palliative care referral and death among patients treated at a comprehensive cancer center. J Palliat Med. 2005;8:1025–1032.

- Good PD, Cavenagh J, Ravenscroft PJ. Survival after enrollment in an Australian palliative care program. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2004;27:310–315.

- Hui D, Elsayem A, De la Cruz M, et al. Availability and integration of palliative care at US cancer centers. JAMA. 2010;303:1054–1061.

- Morita T, Akechi T, Ikenaga M, et al. Late referrals to specialized palliative care service in Japan. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2637–2644.

- Osta BE, Palmer JL, Paraskevopoulos T, et al. Interval between first palliative care consult and death in patients diagnosed with advanced cancer at a comprehensive cancer center. J Palliat Med. 2008;11:51–57.

- Epstein AS, Goldberg GR, Meier DE. Palliative care and hematologic oncology: the promise of collaboration. Blood Rev. 2012;26:233–239.

- McGrath P, Holewa H. Missed opportunities: nursing insights on end-of-life care for haematology patients. Int J Nurs Pract. 2006;12:295–301.

- Odejide OO, Salas Coronado DY, Watts CD, et al. End-of-life care for blood cancers: a series of focus groups with hematologic oncologists. JOP. 2014;10:e396–e403.

- Schenker Y, Crowley-Matoka M, Dohan D, et al. Oncologist factors that influence referrals to subspecialty palliative care clinics. JOP. 2014;10:e37–e44.

- Hui D, Finlay E, Buss MK, et al. Palliative oncologists: specialists in the science and art of patient care. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:2314–2317.

- Hui D, Park M, Liu D, et al. Attitudes and beliefs toward supportive and palliative care referral among hematologic and solid tumor oncology specialists. Oncologist. 2015;20:1326–1332.

- Manitta VJ, Philip JA, Cole-Sinclair MF. Palliative care and the hemato-oncological patient: can we live together? A review of the literature. J Palliat Med. 2010;13:1021–1025.

- Wright B, Forbes K. Haematologists’ perceptions of palliative care and specialist palliative care referral: a qualitative study. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2017;7:39–45.

- Centeno C, Lynch T, Garralda E, et al. Coverage and development of specialist palliative care services across the World Health Organization European Region (2005–2012): results from a European Association for Palliative Care Task Force survey of 53 Countries. Palliat Med. 2016;30:351–362.

- Hoefler JM, Vejlgaard TB. Something’s ironic in Denmark: an otherwise progressive welfare state lags well behind in care of patients at the end of life. Health Policy. 2011;103:297–304.