Abstract

Background: Patients with esophageal cancer seldom achieve long-term survival. This prospective cohort study investigated the selection of patients likely to benefit from curative treatment and whether information on patients’ health-related quality of life (HRQL) would assist treatment decisions in the multidisciplinary team.

Methods: Consecutive patients completed HRQL assessments and clinical data were collected before start of treatment. Logistic regression analyses identified clinical factors associated with treatment intent in patients with stage-III disease. Kaplan–Meier method was used for survival analyses and Cox proportional hazards models were used to assess the impact of clinical factors and HRQL on survival in patients planned for curative treatment.

Results: Patients with curative treatment intent (n = 90) were younger, had better WHO performance status and less fatigue than patients with palliative treatment intent (n = 89). Median survival for the total cohort (n = 179) and patients with palliative or curative treatment intent was nine, five and 19 months, respectively. In multivariate Cox regression analyses, performance status (0–1 favorable) and comorbidity (ASA I favorable) were factors of importance for survival, whereas measures of HRQL were not.

Conclusions: Patients performance status and comorbidity must be considered in addition to stage of disease to avoid extensive curative treatment in patients with short life expectancy. This study did not provide evidence to support that information on patients HRQL adds value to the multidisciplinary team’s treatment decision process.

Background

Despite continuous efforts to improve the outcome for patients with esophageal cancer the prognosis is poor, with a five-year relative survival of 23–24%, in patients with localized disease [Citation1]. The mainstay of curative treatment is surgery with or without preoperative chemoradiotherapy or chemotherapy. Inoperable patients often receive chemoradiotherapy. These treatment regimens are associated with high morbidity and deterioration of patients’ health-related quality of life (HRQL) [Citation2], and thus, the selection of patients likely to benefit from such curative approach is often difficult, but even more important.

The multidisciplinary team (MDT) meeting is the main forum in which cancer patients are discussed and treatment plans are made. Available guidelines are based on evidence from clinical trials on highly selected patient groups [Citation3,Citation4]. Whether the results are representative for patients in clinical practice is often questioned and it is challenging to find the optimal treatment for the individual patient.

Stage of disease according to UICC TNM classification version 7 is the main criterion for treatment decisions. Other determinants also need to be considered, but which to rely on is not established. Candidates are tumor localization, histology, patient’s age, weight loss and general health.

Performance status has been shown to be a prognostic factor for survival in cancer patients and may be measured using observer-rated scores, patient-reported scores or using physical performance tests [Citation5]. Patients’ health can be assessed by patient-reported outcome (PRO) using self-reported questionnaires, such as HRQL instruments with questions related to physical function, respiratory function, psychosocial aspects and symptoms. Several aspects of HRQL have been identified as possible prognostic factors for survival and post-treatment HRQL [Citation6,Citation7], but a standard set of prognostic HRQL variables is not available [Citation8].

Previous studies [Citation9,Citation10] and clinical experience have revealed that for fit patients with localized disease, and for fragile patients with metastatic disease, the MDTs treatment decisions are straight forward. For other patients, in particular those with locally advanced disease (stage III) and good health, the decisions are more challenging.

In order to improve treatment decisions and to better select patients likely to benefit from a curative approach, this paper has the following aims: (1) to identify factors that were important for the MDT’s treatment decision in patients with stage-III disease, (2) to describe patients planned for curative and palliative treatment and (3) to assess the impact of clinical factors and HRQL on survival in patients planned for curative treatment.

Material and methods

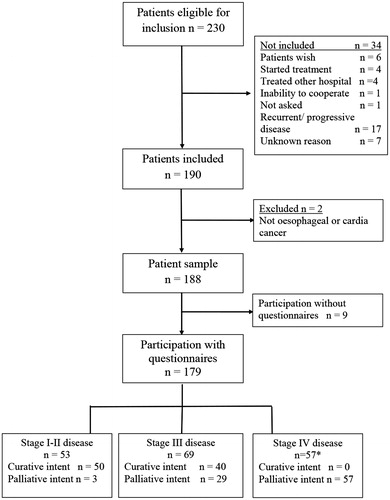

A prospective cohort study of unselected patients with cancer of the esophagus was conducted at Oslo University Hospital (OUS), from June 2010 until May 2012. The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Committee and the hospitals local authorities. All consecutive patients, with primary invasive carcinoma of the esophagus or cardia, referred to the OUS for treatment, were eligible (). OUS is the referral hospital of the southeast health region, covering 56% of the Norwegian population [Citation11].

Figure 1. Flow diagram of the cohort study of patients with esophageal cancer. *One patient without TNM staging, treated with palliative intent.

A written informed consent was obtained before inclusion, and patients willing to participate in the PRO-part of the study completed the first questionnaire (n = 179). Patients unable or unwilling to give informed consent (n = 7), patients with recurrent (n = 9) or progressive disease (n = 8) and patients admitted for second opinion (n = 4) were not included.

Procedures

The patients were examined and treated according to national guidelines and standard procedures at OUS at the time of recruitment [Citation4]. They were discussed at the weekly MDT meeting with a stable group of specialists; surgeons (usually including the endoscopist), oncologists, radiologists and cancer nurses. Pathologists were not part of the MDT meetings but were available for discussions on request. The MDT ensured that necessary diagnostic procedures had been performed. If necessary, additional diagnostic procedures were performed before consensus of the diagnosis and stage of disease was reached. Clinical tumor stage according to UICC TNM was assessed by upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and CT scan of thorax and upper abdomen. Endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) and positron emission tomography (PET) CT were optional. Information concerning the patient’s general health, such as her/his performance status and the American Society of anesthesiologists physical status (ASA) score, were not always available at the time of the MDT meeting. The clinical TNM classification, treatment recommendation and factors that the decision was based on were documented in the patients’ medical records.

Clinical data

Clinical data were collected on a case report form (CRF) during an admission to the hospital before start of treatment. Age, gender, clinical stage of disease, histology, tumor localization and length, comorbidity, smoking and drinking habits, WHO performance status (PS), weight loss, heartburn/dyspepsia and use of analgesics were recorded. In order to assess the functional impact of other disease than the index cancer ASA score was used as follows: person being healthy (grade I), with mild disease (grade II), severe disease (grade III) or with life-threatening disease (grade IV). Dysphagia was scored using Ogilvie’s dysphagia grading scale [Citation12]. Fatigue was defined as weariness from physical and mental exertion. Fatigue, pain and anorexia were scored using The National Cancer Institute Common Terminology for Adverse Events (NCI CTCAE) version 3 (Bethesda, MD).

Available treatment regimens for patients with curative treatment intent were; (1) surgery with or without preoperative chemoradiotherapy (cisplatin +5-fluorouracil (CiFu) + 40 Gy), 2) surgery with preoperative chemotherapy (CiFu or epirubicin + platinum and 5-fluorouracil) and for inoperable patients; (3) chemoradiotherapy (CiFu +50 Gy) or (4) radical radiotherapy (63 Gy + brachytherapy 8 Gy ×1). Standard treatment for patients with metastatic disease and good performance status were palliative chemotherapy (CiFu, epirubicin + platinum and 5-fluorouracil or docetaxel and capecitabine). Patients with local symptoms and patients not eligible for palliative chemotherapy were offered external radiotherapy with or without brachytherapy or endoscopic treatment alone (brachytherapy with or without stent insertion and stent insertion alone). Patients with very poor prognosis (metastatic disease, high age and reduced WHO PS), for whom the burden of treatment was likely to be greater than a possible benefit were offered best supportive care only.

For eligible patients who did not participate, some information (diagnosis, age, gender, clinical stage, ASA score, treatment intent) was collected.

Patient-reported outcome (PRO) and time of assessment

Before the treatment recommendation was discussed with patients, they filled in the following baseline questionnaires: the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) core questionnaire EORTC QLQ-C30 (version 3) [Citation13], the EORTC QLQ-OG25 [Citation14], the Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale (ESAS) [Citation15] and Ogilvie’s dysphagia grading scale [Citation12].

The EORTC QLQ-C30 is a cancer-specific questionnaire that contains five functional scales (physical, role, cognitive, emotional and social), three symptom scales (fatigue, pain and nausea and vomiting) and six single items (dyspnea, appetite loss, insomnia, constipation, diarrhea and financial difficulties). In addition, it includes a global health and quality-of-life scale. The EORTC QLQ-OG25 is a gastro-esophageal-specific questionnaire, designed to increase the specificity and sensitivity of the assessment in the current patient population. It consist of six symptom scales (dysphagia, eating restrictions, reflux, odynophagia, pain and discomfort and anxiety), and 10 single items. In both EORTC forms, the patients answers were scored using a four-point Likert scales ranging from ‘not at all’ (1) to ‘very much’ (4) or from very poor (1) to excellent (7) (EORTC QLQ-C30 questions 29 and 30).

ESAS measure symptoms and contains 10 questions graded on a numerical scale from 0 (symptom is absent) to 10 (worst possible severity). The patient’s answer is reported for each question separately, either graphically or as a numerical value. The values are often categorized as mild or absent (0–3), moderate (4–6) or severe (7–10), but should not be summated.

For this study, a HRQL index score was proposed based on the literature; five frequently reported clinically relevant scales associated with prognosis were selected (global quality of life, physical and role function, fatigue and eating restriction). Low HRQL was defined as function score< 50 or a symptom score >50 in at least three out of five scales based on our clinical judgment and long-time experience in the field. In addition, we used the EORTC QLQ-C30 scoring algorithm to generate a single sum score calculated as the mean of the combined 13 out of 15 scales of EORTC QLQ-C30 (except financial difficulty and global quality of life) [Citation16]. For this purpose, all symptom scale scores were reversed so that higher scores represent better outcomes in all scales.

Statistical methods

Descriptive statistics summarize patients’ characteristics, symptoms and HRQL. For every HRQL scale, the mean and standard deviation (SD) were calculated. All answers were converted mathematically to a 0–100 scale where high score represents a high degree of function or a high degree of symptoms. For the EORTC scales, a difference of ≥10 is regarded as clinically significant [Citation17]. For ESAS, based on local experience and later confirmed by others [Citation18], a difference of two steps was considered clinically significant.

Logistic regression analyses were performed to identify factors associated with curative treatment intent in patients with stage-III disease. Variable selection was done among the following variables: gender, age, N-status, tumor localization, histology, WHO PS, ASA score, weight loss, fatigue and anorexia. Due to the limited number of stage-III patients included in this study, we constructed a model with no more than six variables. Variables with p values <.1 in the univariate analyses were included in the multivariate analyses. Then, backward stepwise elimination was performed for variable selection. We used the variance inflation factor (VIF) to check for multicollinearity. The strengths of the association were presented as odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

The patients were followed from recruitment to time of death or censored if alive at end of study (1 May 2016). Survival was calculated using the Kaplan–Meier method. Comparison of survival curves was performed by log-rank test. Cox regression analyses identified factors associated with survival in patients with curative treatment intent. Clinical and tumor characteristics, as well as the HRQL index score and the EORTC QLQ-C30 sum score were analyzed separately in the univariate analysis. Median EORTC QLQ-C30 sum score was calculated for the total group. Variables with p values <.1 were included in the multivariate analyses. Age at the time of recruitment was included because of clinical relevance. Two different multivariate model analyses (1: including the HRQL index score and 2: including the EORTC QLQ-C30 sum score) were performed. The strengths of the associations were presented as hazard ratios (HR) with 95% CI. p values <.05 (two-sided) were regarded as statistically significant. Correlations between HRQL (EORTC QLQ-C30 functional domains, the HRQL index score and EORTC QLQ-C30 sum score) and observer-rated WHO PS were calculated using Pearson correlation coefficient. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 21.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Among 230 eligible patients, 188 patients with primary disease were included in this study of whom 179 (95%) were willing to participate in the PRO part of the study (). Participants were mainly elderly (≥65 years old) men with good WHO PS, diagnosed with adenocarcinoma in the lower part of esophagus (). Patients not included had similar stage of disease, age and gender distribution but had more often reduced PS (WHO PS 2-3 52%) and slightly more comorbidity (ASA III 25%) than patients included.

Table 1. Patient characteristics.

To confirm the completeness of this cohort, we compared the number of eligible patients approached with the incidence of esophageal cancer in Norway. In 2011, 136 eligible patients were identified at OUS, representing 57% of all patients diagnosed with esophageal cancer in Norway that year (n = 240) and similar to the proportion of patients covered by the southeast health region [Citation11].

Based on clinical TNM staging, 69 of 179 patients in this study had stage-III disease, while 56 patients had metastatic disease. Three patients had T1 tumor treated with surgery (n = 2) or brachytherapy (n = 1) alone. Patients with curative treatment intent had better WHO PS and less weight loss than patients with palliative treatment intent. Three patients with localized disease were planned for palliative treatment due to high age (n = 1) or severe comorbidity combined with reduced WHO PS (n = 2). One out of seven patients with T4 tumor was treated with curative intent.

Forty-two of the 80 patients with symptoms lasting more than three months were planned for curative treatment (). More than 70% of the patients had observer-rated dysphagia. Observer-rated fatigue and anorexia was less frequent in patients with curative treatment intent than in patients with palliative intent. Pain was reported in 50–54% of the patients.

Table 2. Observer-rated symptoms and use of analgesics.

In addition to gastrointestinal endoscopy and histologically verified diagnosis, all patients except two had CT scan of thorax and upper abdomen. EUS was performed in 56 patients (31%) of which 45 had curative treatment intent. FDG PET-CT was performed in 34 patients (19%). Most patients were discussed in the MDT meeting. Patients not discussed had metastatic disease (n = 8) or a second synchronous cancer (n = 1).

In patients with stage-III disease, 58% (40 of 69) had curative treatment intent. They were younger, had better WHO PS and less comorbidity compared to patients with stage-III disease and palliative treatment intent (Supplementary table 1). The multivariate logistic regression analysis identified age (OR =0.89, 95% CI: 0.83–0.96) and WHO PS (0.18, 0.04–0.85) to be significantly associated with curative treatment intent, while gender, N stage, tumor localization, histology, comorbidity, weight loss, fatigue and anorexia were not (). Fatigue was kept in the final model due to its confounding effect on the association between the other variables and the decision of treatment. There was no evidence of multicollinearity (VIF <2).

Table 3. Factors associated with curative treatment intent in patients with stage-III disease, logistic regression (69 patients at risk, 40 patients with curative and 39 with palliative intent).

Planned treatment

The planned curative treatments (90 patients) were: surgery with or without neoadjuvant treatment (n = 54), chemoradiotherapy (n = 19), radical radiotherapy (n = 15) or other treatments (n = 2, brachytherapy alone for one patient with a T1N0M0 tumor, good PS but comorbidity and neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by either surgery or radiotherapy depending on the effect of the chemotherapy for a patient with uncertain N stage). The planned palliative treatments (89 patients) were: external radiotherapy alone (n = 20) or in combination with brachytherapy, chemotherapy or stent (n = 15); chemotherapy with or without stent (n = 30). Twenty-one patients were planned for endoscopically brachytherapy with or without stent (n = 17) or stent insertion alone (n = 4), while three patients were planned for best supportive care only.

Health-related quality of life (HRQL) and patient-reported symptoms

More than 60% of the patients reported a high level of anxiety related to the disease and its future aspects irrespectively of treatment intent (). In both treatment intent groups, a significant number of patients also had impaired global quality of life, reduced sense of well-being and problems related to eating. Patients with curative treatment intent less often reported reduced HRQL and had fewer symptoms compared to patients with palliative treatment intent (). Comparison of the two groups’ mean scores for the HRQL scales and patient-reported symptoms are shown as supplementary (Supplementary table 2).

Table 4. Health-related quality-of-life and patient-reported symptoms at baseline (n = 179).

Survival

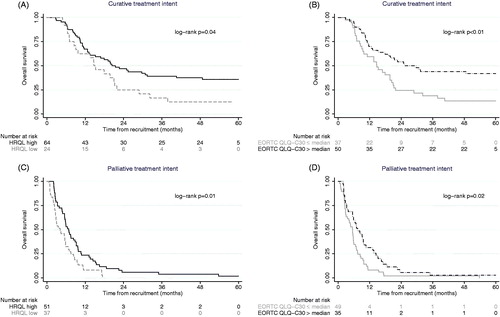

Median overall survival was nine, 19 and five months for the total cohort (n = 179), and for patients with curative (n = 90) and palliative (n = 89) treatment intent, respectively. In patients with stage-III disease, the median survival was 10, 16 and five months for the total cohort (n = 69), the curative group (n = 40) and the palliative group (n = 29), respectively. HRQL as assessed with HRQL index score and the median EORTC QLQ-C30 sum score (75), were associated with survival in both the curative and palliative group ().

Figure 2. Pretreatment health-related quality of life association with survival in patients with curative and palliative treatment intent. Recruitment is date of inclusion, before start of treatment; HRQL: health-related quality of life index score (3 patients with missing score); Median EORTC QLQ-C30 sum score (75) was calculated for the total group (n = 171 with valid information).

In patients treated with curative treatment intent; age, WHO PS, ASA score and HRQL were significantly associated with survival in univariate analyses. In multivariate analyses, WHO PS (0–1 favorable) and ASA score (ASA I favorable) were shown to be factors associated with improved overall survival after adjustment of age and median EORTC QLQ-C30 sum score (). Using HRQL index score, instead of the summary score, did not alter the results. There was no evidence of multicollinearity (VIF <2) in the two models.

Table 5. Cox regression analyses of potential prognostic factors for survival in patients with curative intent (90 patients at risk, 64 deaths).

The correlation between HRQL parameters and WHO PS was good for the EORTC QLQ-C30 physical function scale (0.69), and moderate for the HRQL index score (0.52) and the EORTC QLQ sum score (0.54).

Discussion

This prospective cohort study provides evidence to support that clinical factors, other than stage of disease, need to be reviewed in order to identify patients most likely to benefit from curative treatment. Particularly, information on WHO PS and ASA score seem to be more valuable for the treatment decision process than information on patients’ HRQL. Treatment intent varied most in patients with stage-III disease indicating that selecting the optimal treatment in this group is especially challenging.

The strength of the present study is the completeness of the data providing information on treatment decision, HRQL and survival in a patient cohort representative for patients in clinical practice in our region, and therefore, probably for patients in general.

Age and WHO PS were identified as the strongest predictors for the MDT’s treatment decision in patient with stage-III disease. Higher age has been associated with reduced treatment tolerability, increased risk of side effects and higher risk of postoperative mortality [Citation19]. However, with an increasing proportion of fit elderly patients, it is important to be aware that biological age not necessarily corresponds with chronologic age, and for fit elderly patients curative treatment is possible [Citation20]. It is a problem that elderly patients often are excluded from clinical trials, resulting in lack of information about the treatment effects in this group. PS has been shown to be a prognostic factor for outcome in esophageal cancer [Citation3], and the present results are in line with this. Observer-rated fatigue approached but did not achieve a significant association with the treatment decisions. This is a less distinct concept than WHO PS and may be subject to inconsistent interpretation. However, 88% of the patients were scored by the same clinician (CDA), reducing the risk of inconsistency.

In patients with curative treatment intent, the ASA score and WHO PS were most strongly associated with survival. This suggests that the MDTs need to consider comorbidity more carefully when curative treatment is an option in line with literature reporting comorbidity to increase operative time, length of hospital stay and the rate of postoperative complications after esophagectomy [Citation21]. A recent review found that lack of information on comorbidity in cancer patients hampers MDTs treatment decisions [Citation22]. A full clinical history and thorough examination of the patient prior to the MDT meeting is important. In the current study, ASA score was used for the assessment of comorbidity instead of the Charlson comorbidity index, in order to evaluate the functional impact of other diseases than the index cancer. The ASA score is widely used to describe preoperative physical status, but also to describe comorbidity [Citation23,Citation24]. A recently published study has shown agreement between the ASA score and Charlson comorbidity index score [Citation23] indicating that both systems are applicable for the assessment of comorbidity. Due to the limited number of patients, comparison of survival based on the different treatment regimens was not possible.

In a recently published study, pretreatment HRQL was found to have higher impact on survival than performance status [Citation25]. Patients with high HRQL (FACT E sum score > median) had a better prognosis than patients with low HRQL (FACT E sum score < median) supporting the presumption of an association between patients HRQL and survival. This is contrary to our results. We included a HRQL sum score in the analyses [Citation16] and defined high and low HRQL based on the median value similar to Kidane et al, but it did not provide prognostic value. This may be due to the difference in study populations. Patients included in their study were highly selected: 128 patients from four studies in three institutions, recruited over 18 years.

A disadvantage of sum scores is that the relative importance of the scale scores is not considered. It is a relevant presumption that for instance physical and role function are more related to a patient’s health than cognitive function or constipation is. Another problem is that the definitions of high and low HRQL using median sum scores are not readily used in the clinical setting. It may, however, serve as a platform for further studies to define a sum score threshold valid to be used in clinical practice.

Whether the appropriate aspects were included in the proposed HRQL index score may be questioned; only pretreatment HRQL scores frequently reported to have prognostic value [Citation6,Citation7,Citation26,Citation27] were included. In particular, pretreatment physical function has repeatedly been reported to predict survival [Citation6,Citation27], probably superseding observer-rated PS [Citation27]. This was not confirmed in the current study, although we found a high correlation between patient-reported physical function and WHO PS. Others have reported disagreement between clinician-reported PS and patient-reported PS with clinicians being more likely to rate patients with better PS than patients themselves [Citation28]. Interpretation of HRQL scores can be difficult and our definition of low HRQL for each scale as function <50 or symptom >50 was set to identify patients with significant level of problems and reduced function.

We were surprised that Kidane et al did not find ECOG PS to have prognostic value [Citation25] (WHO PS equals ECOG PS). A possible explanation may be that they compared PS score 0 (fully active) with score 1 (restricted in strenuous activities) and that the difference between these two scores is less relevant for survival than comparing ECOG PS 0/1 with ECOG PS scores ≥2 (unable to carry out any work activities). Whether a patient has ECOG PS 0 or 1 is less likely to impact on the treatment decision.

Even though we failed to prove that pretreatment HRQL data added value to the treatment decision, information on patients HRQL is still important to identify problems and to provide adequate palliation of symptoms irrespective of the treatment decision. It has been repeatedly demonstrated that clinicians are poor judges of patients’ symptoms [Citation28,Citation29], and we recommend collection of PRO before start of treatment. As expected, patients with palliative treatment intent had more problems and higher symptom burden than patients with curative treatment intent. The majority of all patients reported a high level of anxiety, independent of treatment intent and disease stage, probably reflecting that the HRQL assessment was performed prior to the clinical consultation giving them information about treatment and prognosis. This high level of anxiety may cause a barrier to communication and shared treatment decision making. Whether patients really have an informed choice regarding the treatment plan and its implications is uncertain. The use of PRO might assist in this process.

As expected, clinical stage of disease was the overall most important factor for the decision of treatment intent by the MDT. Despite that stage of disease is widely accepted as an important prognostic factor in esophageal cancer, the risk of inaccurate clinical TNM classification is a well-known problem. N stage was not associated with survival in patients treated with curative intent. For most of our patients, stage of disease was based on endoscopy and CT scan results. However, it is often difficult to distinguish between a T2 and T3 lesions based solely on CT images, including substantial limitations concerning N stage. EUS, considered to be superior to CT scans in both tumor and node staging [Citation30], was performed in 50% of the patients with curative intent. Increased use of EUS at our hospital would probably improve the accuracy of the staging process. Nevertheless, the continuous participation by the same experienced radiologists and endoscopist, were likely to increase the precision of the staging process.

In conclusion, next to clinical stage of disease, this study support that patients’ WHO PS and comorbidity are the most important factors to rely on in the treatment decision process. On this background, the risk of giving extensive curative treatment to patients with short life expectancy can be reduced. Although HRQL data is important to identify patient’s concern and to provide adequate palliation, it does not seem to add value to the MDTs treatment decision process.

IONC_A_1346379_Supplementary_Information.zip

Download Zip (23.8 KB)Acknowledgments

Study nurse Cecilie Lange provided excellent work in data management and patient follow-up and the Norwegian Cancer Society (project number 160866) provided financial support.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Cancer Registry of Norway. Cancer in Norway 2015 – Cancer incidence, mortality, survival and prevalence in Norway. Available from: www.kreftregisteret.no. 2016.

- Lagergren P, Avery KN, Hughes R, et al. Health-related quality of life among patients cured by surgery for esophageal cancer. Cancer. 2007;110:686–693.

- Allum WH, Blazeby JM, Griffin SM, et al. Guidelines for the management of oesophageal and gastric cancer. Gut. 2011;60:1449–1472.

- Helsedirektoratet. Nasjonalt handlingsprogram med retningslinjer for diagnostikk, behandling og oppfølging av spiserørskreft. 2015.

- Verweij NM, Schiphorst AH, Pronk A, et al. Physical performance measures for predicting outcome in cancer patients: a systematic review. Acta Oncol. 2016;55:1386–1391.

- Blazeby JM, Brookes ST, Alderson D. The prognostic value of quality of life scores during treatment for oesophageal cancer. Gut. 2001;49:227–230.

- Healy LA, Ryan AM, Moore J, et al. Health-related quality of life assessment at presentation may predict complications and early relapse in patients with localized cancer of the esophagus. DisEsophagus. 2008;21:522–528.

- Chang YL, Tsai YF, Chao YK, et al. Quality-of-life measures as predictors of post-esophagectomy survival of patients with esophageal cancer. Qual Life Res. 2016;25:465–475.

- Amdal CD, Jacobsen AB, Sandstad B, et al. Palliative brachytherapy with or without primary stent placement in patients with oesophageal cancer, a randomised phase III trial. Radiother Oncol. 2013;107:428–433.

- Amdal CD, Jacobsen AB, Tausjo JE, et al. Radical treatment for oesophageal cancer patients unfit for surgery and chemotherapy. A 10-year experience from the Norwegian Radium Hospital. Acta Oncol. 2010;49:209–218.

- Cancer Registry of Norway. Cancer in Norway 2011 – Cancer incidence, mortality, survival and prevalence in Norway. Available from: www.kreftregisteret.no. 2013.

- Ogilvie AL, Dronfield MW, Ferguson R, et al. Palliative intubation of oesophagogastric neoplasms at fibreoptic endoscopy. Gut. 1982;23:1060–1067.

- Bjordal K, deGraeff A, Fayers PM, et al. A 12 country field study of the EORTC QLQ-C30 (version 3.0) and the head and neck cancer specific module (EORTC QLQ-H&N35) in head and neck patients. EurJCancer. 2000;36:1796–1807.

- Lagergren P, Fayers P, Conroy T, et al. Clinical and psychometric validation of a questionnaire module, the EORTC QLQ-OG25, to assess health-related quality of life in patients with cancer of the oesophagus, the oesophago-gastric junction and the stomach. Eur J Cancer. 2007;43:2066–2073.

- Bruera E, Kuehn N, Miller MJ, et al. The Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS): a simple method for the assessment of palliative care patients. J Palliat Care. 1991;7:6–9.

- Giesinger JM, Kieffer JM, Fayers PM, et al. Replication and validation of higher order models demonstrated that a summary score for the EORTC QLQ-C30 is robust. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;69:79–88.

- Osoba D, Rodrigues G, Myles J, et al. Interpreting the significance of changes in health-related quality-of-life scores. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:139–144.

- Bedard G, Zeng L, Zhang L, et al. Minimal clinically important differences in the Edmonton symptom assessment system in patients with advanced cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013;46:192–200.

- Koppert LB, Lemmens VE, Coebergh JW, et al. Impact of age and co-morbidity on surgical resection rate and survival in patients with oesophageal and gastric cancer. Br J Surg. 2012;99:1693–1700.

- Schonnemann KR, Mortensen MB, Bjerregaard JK, et al. Characteristics, therapy and outcome in an unselected and prospectively registered cohort of patients with gastro-oesophageal cancer. Acta Oncol. 2014;53:385–391.

- Dolan JP, Kaur T, Diggs BS, et al. Impact of comorbidity on outcomes and overall survival after open and minimally invasive esophagectomy for locally advanced esophageal cancer. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:4094–4103.

- Stairmand J, Signal L, Sarfati D, et al. Consideration of comorbidity in treatment decision making in multidisciplinary cancer team meetings: a systematic review. Ann Oncol. 2015;26:1325–1332.

- Lavelle EA, Cheney R, Lavelle WF. Mortality prediction in a vertebral compression fracture population: the ASA Physical Status Score versus the Charlson Comorbidity Index. Int J Spine Surg. 2015;9:63.

- Dali D, Howard T, Mian Hashim H, et al. Introduction of minimally invasive esophagectomy in a Community Teaching Hospital. JSLS. 2017;21:e2016.00099.

- Kidane B, Sulman J, Xu W, et al. Pretreatment quality-of-life score is a better discriminator of oesophageal cancer survival than performance status. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2017;51:148–154.

- Chau I, Norman AR, Cunningham D, et al. Multivariate prognostic factor analysis in locally advanced and metastatic esophago-gastric cancer–pooled analysis from three multicenter, randomized, controlled trials using individual patient data. JCO. 2004;22:2395–2403.

- Fang FM, Tsai WL, Chiu HC, et al. Quality of life as a survival predictor for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma treated with radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;58:1394–1404.

- Schnadig ID, Fromme EK, Loprinzi CL, et al. Patient-physician disagreement regarding performance status is associated with worse survivorship in patients with advanced cancer. Cancer. 2008;113:2205–2214.

- Pearcy R, Waldron D, O'boyle C, et al. Proxy assessment of quality of life in patients with prostate cancer: how accurate are partners and urologists? J R Soc Med. 2008;101:133–138.

- Wani S, Das A, Rastogi A, et al. Endoscopic ultrasonography in esophageal cancer leads to improved survival rates: results from a population-based study. Cancer. 2015;12:194–201.