Abstract

Introduction: Despite an intensive screening activity, the incidence of cervical cancer in Denmark has remained stable for the last 15 years, while regional differences have increased. To search for explanations, we investigated possible weaknesses in the screening program.

Material and methods: Data on the screen-targeted women were retrieved from Statistics Denmark. Data on screening activity were retrieved from the annual reports from 2009 to 2015 on quality of cervical screening. Coverage was calculated as proportion of screen-targeted women with at least one cytology sample within recommended time intervals. Insufficient follow-up was calculated as proportion of abnormal and unsatisfactory samples not followed up within recommended time intervals. Diagnostic distribution was calculated for samples with a satisfactory cytology diagnosis.

Results: Coverage remained stable at 75%–76% during the study period. Annually, approximately 100,000 women are screened before they are eligible for invitation, and 600,000 invitations and reminders are issued resulting in screening of 200,000 women. In 2009, 21% of abnormal and unsatisfactory samples were not followed up within the recommended time interval; a proportion that had decreased to 15% in 2015. Overall, 11% of satisfactory samples with a cytology diagnosis were abnormal, but with surprising variation from 6% to 15% across regions.

Discussion: The success of a screening program depends first of all on coverage and timely follow-up of abnormal findings. Our analysis indicated that the currently high incidence of cervical cancer in Denmark may partly be due to low screening coverage. Also worrisome is a high proportion of non-timely follow-up of abnormal findings. Innovative ways to improve coverage and follow-up are urgently needed.

Introduction

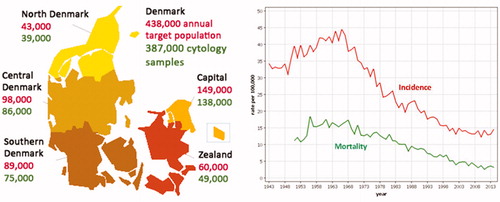

Denmark has a high background risk of cervical cancer. This is illustrated by an incidence of more than 40 per 100,000 (Nordic Standard Population) in the prescreening period of the early 1960s [Citation1], and by the present 20% prevalence of high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV)-DNA [Citation2]. Denmark is now one of the nine European countries with a completed rollout of a population-based national cervical screening program [Citation3–4]. After almost 50 years of screening, the incidence of cervical cancer is now down to the present level of 13.7 per 100,000 (Citation1]. However, despite the intensive screening program with an annual number of about 400,000 cervical samples taken in 1.5 million women of screening age, the incidence of cervical cancer in Denmark has been almost stable during the past 15 years, 2000–2014, . It is difficult to know how the risk of cervical cancer would have developed in Denmark if no screening had taken place. The prevalence over time of HPV infection could have varied, as seen for instance for gonorrheal infection [Citation5]. Prevalence of tobacco smoking in women reached its peak in the late 1970s, and has since decreased from a level of about 50% [Citation6] to about 20% [Citation7].

Figure 1. Number of screen-targeted women in Denmark 1 January 2016 ((women aged 23–49 years/3) + (women aged 50–64 years)/5)) and number of cytology samples 2015 by region. Age-standardized incidence and mortality (Nordic standard population) of cervical cancer per 100,000 in Denmark 1943–2014.

The incidence of cervical cancer decreased from 19.1 per 100,000 in 1985–1999 to 13.7 per 100,000 in 2000–2014. But the decrease was unevenly distributed throughout the five Danish regions. While there was only a 7% difference between the region with the highest and the region with the lowest incidence in 1985–1999, this difference had increased to 26% in 2000–2014. This was explained by a decrease over time in the incidence in the Capital and the Zealand regions of only 21%–23%, while the incidence in Funen and Jutland decreased by 33%–37% [Citation1].

In 2009, the Danish Quality Database for Cervical Screening (DKLS) was established and selected quality indicators started to be published on an annual basis. The purpose of the present paper was to use these quality assurance data to investigate to what extent the stagnation in cervical cancer incidence nationwide and the development of regional differences were related to differences in the quality of the screening.

Material and methods

Screening in Denmark

The Danish regions (earlier counties) are responsible for cervical screening. The Danish Health Authority issued recommendations for the screening in 1986 [Citation8], in 2007 [Citation9], and in 2012 [Citation10]. After 1986, Denmark implemented a so-called integrated screening program. This meant that all cytology samples were registered centrally, and only women not registered with a sample within the recommended time interval were invited for screening. The purpose was to reduce opportunistic screening. The counties (later regions) were recommended to offer women aged 23–59 years cytology screening every third year [Citation11], and samples should be taken by the general practitioner (GP). While all counties by 1996 had some organized screening, it took 20 years before the 1986 recommendations were fully implemented [Citation12]. In 2007, the recommendations were changed to invitation of women aged 23–49 years every third year, and of women aged 50–64 years every fifth year ().

Table 1. Cervical cancer incidence in Denmark by region 1985–1999 and 2000–2014.

In 2007, pathology departments were recommended to use the Bethesda classification for cervical cytology, and the recommended follow-up of abnormal findings was specified in diagrams. In addition, HPV-DNA triage of atypical cells of undetermined significance (ASCUS) for women above the age of 30 years, alternatively HPV-RNA triage of women with ASCUS/low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL) independently of age, was recommended [Citation9]. In 2012, an HPV check-out-test was recommended to replace cytology for women aged 60–64 years. It is possible for women to inform their region, if they do not want to be invited for screening [Citation10]. Severe abnormal findings are referred directly for colposcopy including biopsies. Minor findings in women below age 30 years are followed up with repeated testing, while minor findings in women from age 30 and above are triaged with HPV-testing, and referred for colposcopy if the HPV-test is positive.

Danish quality database for cervical screening

The input to this database is retrieved from the Central Population Register (CPR), from the Nationwide Pathology Register (Patobank), which includes data on all histology and cytology in Denmark, and from the Danish Cancer Register. The target population for screening is identified from the CPR. The invitations to screening, reminders, participation and screening outcome data come from the Patobank. Data from the two data sets are linked for each individual woman based on the personal identification number used in both data sets. From this database, an annual DKLS-report started to be published in 2009 [Citation13,Citation14], and it reports on a number of quality indicators inspired by the European guidelines [Citation15]: proportion of cytology laboratories analyzing more than 15,000 (later changed to more than 25,000) sample per year; participation rate among women invited to screening; percentage of unsatisfactory samples; percentage of samples answered within 10 days; percentage of ASCUS >30 years with HPV-triage; coverage; percentage of abnormal and unsatisfactory samples not followed up within recommended time intervals; and number of cervical cancer cases. As an additional indicator, audit of screening history for women diagnosed with cervical cancer is being developed, but data have so far not been reported.

We will report here on the time trends and the regional differences in the quality indicators expected to be most important for the incidence of cervical cancer [Citation13,Citation16–21]. These are coverage and percentage of abnormal and unsatisfactory samples not followed up within recommended time intervals. Although not a quality indicator, we will report also on the diagnostic distribution of cytology samples reported from 2013 to 2015.

Coverage is calculated for a given date as follows: for women aged 23.5–50.4 years, the proportion with at least one cytology sample within the last 3.5 years, and for women aged 50.5–65.4 years the proportion with at least one cytology sample within the last 5.5 years. All cytology samples are included in the calculation independently of whether it is taken spontaneously or after invitation. Coverage is a better measure of the extent to which the population is protected by screening, as participation reflects only the response to invitations.

Non-timely follow-up is calculated as the proportion of cytology samples with a given follow-up recommendation for which a follow-up sample is not registered in the Patobank within the recommended time interval. The recommended follow-up intervals vary from 3 to 12 months depending on the severity of the abnormal finding. A separate calculation is therefore made also for the most severe abnormalities, high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL), adenocarcinoma in-situ (AIS), atypical squamous cells, cannot rule out high-grade squamous intra-epithelial lesion (ASCH) and atypical glandular cells (AGC).

The diagnostic distribution published for the cytology samples includes the categories ‘unsatisfactory’ and ‘other’. The proportion of ‘unsatisfactory’ samples is dependent on whether conventional or liquid-based cytology is used. The proportion of ‘other’ samples represents HPV-tests taken in women above the age of 60 years. In order to obtain a proper comparison of the diagnostic distribution of cytology across regions, the ‘unsatisfactory’ and ‘other’ samples have therefore been excluded.

Ethics

All data in this paper are quoted from publicly available databases.

Results

In 2015, a total of 438,000 women were targeted by the screening program, and 387,000 cytology samples were taken (). The coverage in the Danish cervical screening program is low, varying between 75% and 76% during the past 7 years. There have, however, been only minor differences of only 1%–3% between the regions with the highest and the lowest coverage, .

Table 2. Coverage in percent of target population by cervical screening in Denmark 2009–2015 by region.

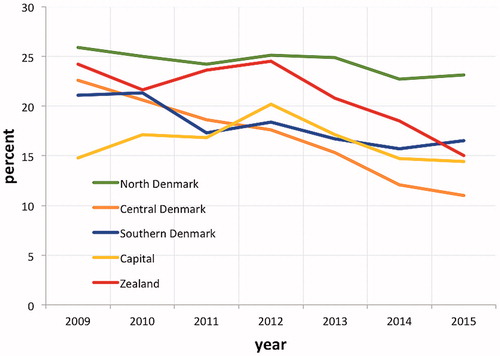

The percentage of abnormal and unsatisfactory cytology samples not followed up within the recommended time interval on a national basis decreased from 20.7% in 2009 to 15.1% in 2015, . This development was most marked in the Central Denmark Region, where the percentage decreased from 22.6% in 2009 to 11.0% in 2015. The Capital Region started out with the lowest percentage in 2009 of 14.8%, but on the other hand overall remained at this level with 14.4% in 2015. While a downward trend was seen throughout the period in the Central Denmark Region, a downward trend was seen in the Region of Southern Denmark in the beginning of the period, where after it stabilized, and a downward trend started late in Region Zealand. The North Denmark Region remained at a high level throughout the period, . The percentage of severe abnormalities not followed up in 120 days (the 3 recommended months +1 extra month) decreased on a national basis from 7.5% in 2009 to 4.1% in 2015. The numbers are too small for analysis of the trend by region.

Figure 2. Percent of abnormal and unsatisfactory cytology samples not followed up within recommended time interval by region, 2009–2015.

Table 3. Percent of abnormal and unsatisfactory findings not followed up within recommended time interval by region, and percent of severe abnormalities (HSIL, AIS, ASCH and AGC) not followed up within recommended time interval.

During 2013–2015, in total 10.7% of satisfactory cytology samples in Denmark showed abnormalities as defined by ASCUS+; of these, 3.0% were ASCUS and 7.7% higher than ASCUS, . There was a considerable variation across regions in the percentages of abnormal samples. For ASCUS+, the percentage was 156% higher for Region Zealand than for the Capital Region. This pattern was repeated both for ASCUS and for >ASCUS.

Table 4. Percent of ASCUS+, ASCUS and > ASCUS of satisfactory cytology samples by region in Denmark in 2013–2015.

Discussion

Main findings

As cervical dysplasia (cervical intraepithelial neoplasia, 1–3) does not cause symptoms, coverage by screening is the most important factor for the success of a screening program. Within the last 7 years, the coverage in Denmark remained at 75%–76%. This means that one fourth of Danish women do not follow the recommended screening intervals, and these women harbor almost half of the cervical cancer cases in the relevant age-groups [Citation22]. At the national level, coverage increased to 79% when the target population was corrected for hysterectomized women [Citation23]. While the relatively high incidence of cervical cancer in Denmark can thus partly be attributed to the low screening coverage, there was no indication for the low coverage to explain the regional differences in the incidence, as coverage did not vary between regions.

The homogeneity in coverage across regions is remarkably, as screening coverage is often lower in urban than in rural settings. This is seen in for instance Sweden, where the national coverage is 80%, but only 75% in Stockholm [Citation24]. The coverage in young women has been slightly below that of the average coverage, but in contrast to the development in certain other countries, the coverage in young Danish women has been stable over time. Between 1995 and 2007, the coverage in women aged 25–29 years varied between 68% and 70% [Citation25].

In the European perspective, coverage is high in Denmark; in 2013, Denmark was among the four EU-countries (Denmark, Ireland, Sweden and UK Northern Ireland) with an examination coverage about 80% [Citation3]. It should be noted though, that there is a considerable variation over years in the number of cytology samples taken in Denmark; in 2013, the number was 458,000 as opposed to 387,000 in 2015. The EU-reported coverage based only on data from 2013 is therefore higher than the coverage reported here, where each woman has been followed backwards in her respective screening interval. Norway and Sweden have invitation systems similar to the Danish one. With calculations similar to the one presented here, coverage in Norway is at present 68% [Citation26], while it is 80% in Sweden [Citation24]. Coverage in Denmark is thus at the average of the coverage in these neighboring countries.

Screening makes no sense unless women with abnormal findings are actually followed up and eventually treated. It was therefore worrisome when the first quality assurance report from 2009 showed that one fifth of abnormal and unsatisfactory findings were not followed up within the recommended time intervals. On this basis, two new initiatives were taken. First, in May 2011 the Danish Health Authority issued new legally binding guidelines for follow-up of paraclinical tests [Citation27]. Second, in February 2012, routine reminders started to be send from the Patobank to the GPs in case of missing follow-up, and although these reminders are sent only after the deadline for follow-up they may have had an overall preventive effect. However, changes in technology may have been the most important factor behind the decrease in non-timely follow-up. At the national level in 2009, 3.3% of cytology samples were unsatisfactory, but as conventional cytology was gradually replaced by liquid-based cytology this proportion decreased to 1.3% in 2015. The Region of Southern Denmark and most of the Capital Region used liquid-based cytology already in 2009; the Central Denmark Region converted to liquid-based cytology in 2010; Zealand Region from 1 June 2013; and the North Denmark Region used conventional cytology throughout the study period. Abnormal samples over time thus constituted an increasing proportion of samples not followed up timely.

It is difficult to determine to what extent non-timely follow-up has contributed to the relatively high incidence of cervical cancer in Denmark, but it is certainly a factor that potentially diminishes the effect of screening. In a follow-back study of cervical cancer cases diagnosed in 1997–2002 in Aarhus, Denmark, 5% of the cases could be attributed to failure in follow-up [Citation28]. Fortunately, late follow-up does occur. In 2015, only 1% of severe abnormalities were not followed up within 450 days [Citation21]. An in-depth study in 2014 showed that 16 severe abnormalities had follow-up after 450 days; 13 women had at that time emigrated or died; so only 45 out of originally 9341 women with severe abnormalities remained without long-term follow-up [Citation20]. The number of samples with non-timely follow-up has varied across sample takers; for severe abnormalities from 0 to 25 in 2015 [Citation21].

Data on proportion of abnormal cytology findings have been reported only for the last 3 years, 2013–2015, and it does therefore not make sense to analyze the time trend. It was remarkably, though, that the Capital Region systematically had much lower proportions of abnormal findings than the other regions. The low proportion of ASCUS in the Capital Region was due to recoding of these samples to normal if the HPV-triage was negative, a practice changed only from 1 January 2017. Given that the Capital Region has also a remarkably low proportion of > ASCUS samples, the data do, however, indicate a generally more conservative diagnostic policy in the Capital than in other regions. The 7.7% of abnormalities more severe than ASCUS at the national level seems high. It should be remembered though that both screening, follow-up and control samples are included, and that unsatisfactory samples are excluded from the denominator. Given the latency time, it is uncertain to what extent the regional differences in ASCUS + detection can explain the regional differences in cervical cancer incidence.

The key quality assurance indicators thus provide a valuable basis for improvement of the national screening program, but do not explain the regional differences in incidence of cervical cancer.

Ways for improvement

Coverage

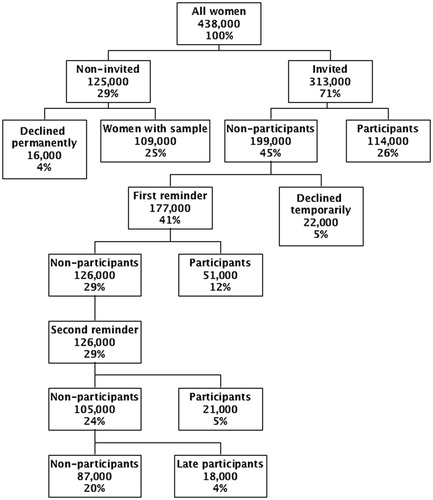

Coverage has remained stable over time, and 2015 can therefore be used to illustrate the activities. In , number of screen-targeted women is defined as women aged 23–49 years at 1 January 2016 divided by 3, and aged 50–64 years divided by 5 [Citation29], and the numbers of activities are taken from the DKLS-report from 2015 [Citation21]. Put together these numbers give a slightly lower total coverage of 72% than the 75% found by the calculation method used in the DKLS-report, reflecting the dynamic of the screening population. The numbers in anyhow provide an overview of the activities in the screening program. In 2015, after 600,000 invitations and reminders, about 200,000 women attended screening. This means on average three letters per screened woman. Electronic messages are expected to replace physical letters in the screening program in the near future. It remains to be seen how this will affect coverage.

Figure 3. Flow diagram for screening activities in Denmark in 2015. Notes: All women: ((Women aged 23–49 years/3) + (women aged 50–64 years/5)) by 1 January 2016; Declined permanently: hysterectomized women, and women who had resigned from the program permanently; Declined temporarily: women not screened within 90 days of invitation and not reminded; Participants: women with a cytology sample within 90 days of invitation/reminder; Late participants: other women with a cytology sample within 365 days of invitation. Due to the dynamic in the screening population over time, this group will partly overlap with ‘declined temporarily’.

About 100,000 women had already a sample taken before they were due for invitation. A certain proportion of these women will be in follow-up and control. The rest of these women are expected to have undergone opportunistic screening with either a shorter time interval than recommended, so-called sporadic opportunistic screening, or a time-interval longer than 90 days after the second reminder, so-called routine opportunistic screening [Citation30]. Routine opportunistic screening might be a way to screen a hard-to-reach group, and a woman should always have the opportunity to have a sample taken in case of symptoms or suspicions. It is therefore difficult to draw a firm line between justified and non-justified samples. It is clear though that sporadic opportunistic screening is expensive, and that this is not the way to increase coverage.

In the Capital Region, a random sample of non-attenders was invited for self-sampling for HPV-testing in 2014/15 [Citation31]. Divided into 24 batches over a period of approximately 1 year, 23,632 women were scheduled for invitation. Of these, 974 women had a physician-taken sample registered prior to invitation; 4824 returned the self-sampling brush; and 2288 had a physician-taken sample registered after invitation. The response rate can thus be estimated to 28%, which is better than the 17% short-term response to the second reminder. In combination with the other numbers in , self-sampling could bring coverage close to 80%. In the Central Denmark Region a randomized controlled trial is under way comparing self-sampling with the second reminder [Citation32]. It is clear that coverage remains a challenge and that new ways of approaching this are warranted.

Follow-up of abnormal findings

The transition to liquid-based cytology, the new legally binding guidelines for follow-up of paraclinical tests, and probably also the implementation of routine reminders from the pathology departments to the GPs all helped to decrease the proportion of samples not follow-up timely. From before to after the reminders to the GPs, a decrease from 26% to 15% was observed for samples not followed up within 12 months among samples that should have been followed up within 6 months [Citation33]. As of 2015, however, still 15% of samples were not followed up timely. Results of cervical screening are sent to the GP only. The Danish Health Authority in 2012 recommended that results should also be sent to the women. The implementations of this system has, however, been postponed to await an electronic solution that has so far not materialized. In 2012, the Central Denmark Region started a cluster randomized controlled trial with direct information of the screening result to the women. The dedicated information policy in the Central Denmark Region has been followed by a decline in non-timely follow-up from 22% in 2009 to 11% in 2015. System failures seem to be the main explanations for lack of timely follow-up in Denmark.

Cytology

There was a marked difference between the proportions of ASCUS + samples in the Capital Region as compared with the other regions. Comparison of reading and coding practice across regions could help to reveal reasons for these differences. Possible quality differences in cytology reading will be overcome when HPV-testing is expected to replace cytology as the primary screening test, as it is already the case in the Netherlands [Citation34] and partly in Sweden [Citation35].

Strengths and weaknesses

The Danish register data provide a good opportunity for disentangling elements of the screening ‘machinery’. But there are also limitations. With the long latency time between an abnormal cytology and the potential occurrence of cervical cancer, it is clear that we cannot expect a straightforward correlation between the present incidence of cervical cancer and the present quality of screening. This is in particular the case for regional data, where the numbers may be small, and where the previous screening policy has varied for those generations now above screening age.

Perspectives

Despite 50 years of screening, Denmark still struggles with low coverage, non-timely follow-up of abnormal findings, and surprisingly large regional differences in screening diagnostics. While HPV-vaccination is a promising perspective, screening will still be needed for control of cervical cancer in older, non-vaccinated women, and unfortunately also in younger generations not following the vaccination program [Citation36]. New innovative ways to increase coverage and empowerment of women to ensure follow-up of abnormal findings are needed. This is relevant both for the present cytology-based screening program and for a foreseen HPV-based screening program.

Disclosure statement

Elsebeth Lynge: Roche provides test kits free of charge for a randomized controlled trial. Participated in meetings with Roche with fees paid to the University of Copenhagen.

Berit Andersen: Test kits for HPV-project delivered free of charge by Roche. Self-sampling devises for HPV-project delivered free of charge by Axlab. Participation in Eurogin 2016 paid by Roche.

Carsten Rygaard: Participated in meeting with Roche with fee paid to the University of Copenhagen.

Marianne Waldstrøm: Participation in meetings sponsored by Roche and Merck. Fees paid by Merck to Vejle Hospital. HPV tests at reduced price from Roche for study.

No conflict of interest for remaining authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Engholm G, Ferlay J, Christensen N, et al. NORDCAN: Cancer incidence, mortality, prevalence and survival in the Nordic countries, Version 7.3 (08.07.2016) [Internet]. Association of the Nordic Cancer Registries. Danish Cancer Society. [cited 2017 May 4]. Available from: http://www.ancr.nu

- Kjær SK, Munk C, Junge J, et al. Carcinogenic HPV prevalence and age-specific type distribution in 40,382 women with normal cervical cytology, ASCUS/LSIL, HSIL or cervical cancer: what is the potential for prevention? Cancer Causes Control. 2014;25:179–189.

- Screening Group. International Agency for Research on Cancer. Cancer screening in the European Union. Report on the implementation of the Council Recommendation. European Commission, 2017. [cited 2017 Jul 3] https://ec.europa.eu/health/…/2017_cancerscreening_2ndreportimplementation_en.pdf

- Cancer Registry of Norway. [cited 2017 Jul 3]. Available from: https://www.kreftregisteret.no/screening/livmorhalsprogrammet/ (in Norwegian).

- Lynge E, Jensen OM. Cohort trends in incidence of cervical cancer in Denmark in relation to gonorrheal infection. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1985;64:291–296.

- Osler M, Prescott E, Gottschau A, et al. Trends in smoking prevalence in Danish adults, 1964–1994. Scand J Soc Med.1998;4:293–298.

- Hansen H, Johnsen NJ, Molsted S. Time trends in leisure time physical activity, smoking, alcohol consumption and body mass index in Danish adults with and without COPD. BMC Pulm Med 2016;16:110. DOI 10.1186/s12890-016-0265-6.

- Sundhedsstyrelsen. Preventive Examinations for Cervical Cancer Committee on Cervical Cancer Examinations. Copenhagen: National Board of Health (Sundhedsstyrelsen); 1986. Danish.

- Sundhedsstyrelsen [webpage on the Internet]. Screening for cervical cancer – recommendations. Copenhagen: National Board of Health (Sundhedsstyrelsen); 2007. [In Danish]. [cited 2015 Aug 14] Available from: https://sundhedsstyrelsen.dk/da/sundhed/folkesundhed/screeningsprogrammer/livmoderhalskraeftscreening#.

- Sundhedsstyrelsen [webpage on the Internet]. Screening for cervical cancer – recommendations. Copenhagen: National Board of Health (Sundhedsstyrelsen); 2012. [In Danish – with summary in English]. Available from: https://sundhedsstyrelsen.dk/da/sundhed/folkesundhed/screeningsprogrammer/livmoderhalskraeftscreening#. [cited 2015 Aug 14]. Forebyggende undersøgelser for livmoderhalskræft i Denmark. Status i 1995. Planer for 1996 [Preventive examinations for cervix cancer in Denmark].

- IARC working group on evaluation of cervical cancer screening programmes. Screening for squamous cervical cancer: duration of low risk after negative results of cervical cytology and its implication for screening policies. BMJ 1986;293:650–664.

- Lynge E, Arffmann E, Behnfeld L, et al. Status in 1995. Plans for 1996. Ugeskr Laeger 1996;158:4916–4919. Danish.

- Styregruppen for DKLS [webpage on the Internet]. DKLS Annual Report 2009, Dansk Kvalitetsdatabase for Livmoderhalskræftscreening; 2010 [In Danish]. [cited 2016 Jan 14] Available from: http://danskpatologi.dk/doc/DSPAC_pdf/%C3%85rsrapport%20DKLS%202009_final.pdf.

- Rygaard C. The Danish quality database for cervical cancer screening. Clin Epidemiol. 2016;8:655–660.

- European Commission, Directorate General for Health and Consumers. European guidelines for quality assurance in cervical cancer screening. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities; 2008.

- Styregruppen for DKLS [webpage on the Internet]. DKLS Annual Report 2010. Dansk Kvalitetsdatabase for Livmoderhalskræftscreening; 2011 [in Danish]. [cited 2016 Jan 14] Available from: https://www.sundhed.dk/content/cms/80/1880_aarsrapport-2010-livmoderhalskraeftscreening.pdf.

- Styregruppen for DKLS [webpage on the Internet]. DKLS Annual Report 2011. Dansk Kvalitetsdatabase for Livmoderhalskræftscreening; 2012 [In Danish]. [cited 2016 Jan 14] Available from: https://www.sundhed.dk/content/cms/82/4682_dkls-%C3%A5rsrapport-2011-dfs-270612.pdf.

- Kompetencecenter for Epidemiologi og Biostatistik Nord (KCEB Nord) [webpage on the Internet]. DKLS Annual Report 2012. Dansk Kvalitetsdatabase for Livmoderhalskræftscreening; 2013 [in Danish]. [cited 2016 Jan 14] Available from: https://www.sundhed.dk/content/cms/82/4682_dkls-%E5rsrapport-2012.pdf.

- Kompetencecenter for Epidemiologi og Biostatistik Nord (KCEB Nord) [Internet]. DKLS Annual Report 2013. Dansk Kvalitetsdatabase for Livmoderhalskræftscreening; 2014 [in Danish]. [cited 2016 Jan 14]. Available from: https://www.sundhed.dk/content/cms/82/4682_dkls-%C3%A5rsrapport-august_vers3-8_final.pdf

- Kompetencecenter for Epidemiologi og Biostatistik Nord (KCEB Nord) [webpage on the Internet]. DKLS Annual Report 2014. Dansk Kvalitetsdatabase for Livmoderhalskræftscreening; 2015 [in Danish]. [cited 2015 Aug 14] Available from: https://www.sundhed.dk/sundhedsfaglig/kvalitet/kliniske-kvalitetsdatabaser/screening/livmoderhalskraeftscreening/

- Kompetencecenter for Epidemiologi og Biostatistik Nord (KCEB Nord) [webpage on the Internet]. DKLS Annual Report 2015. Dansk Kvalitetsdatabase for Livmoderhalskræftscreening; 2016 [in Danish]. [cited 2017 May 4] Available from: https://www.sundhed.dk/sundhedsfaglig/kvalitet/kliniske-kvalitetsdatabaser/screening/livmoderhalskraeftscreening/

- Dugué PA, Lynge E, Bjerregaard B, et al. Non-participation in screening: the case of cervical cancer in Denmark. Prev Med. 2012;54:266–269.

- Lam JU, Lynge E, Njor SH, et al. Hysterectomy and its impact on the calculated incidence of cervical cancer and screening coverage in Denmark. Acta Oncol. 2015;54:1136–1143.

- Elfström KM, Sparén P, Olausson P, et al. Registry-based assessment of the status of cervical screening in Sweden. J Med Screen. 2016;23:217–226.

- Lancucki L, Fender M, Koukari A, et al. A fall-off in cervical screening coverage of younger women in developed countries. J Med Screen. 2010;17:91–96.

- Kreftregisteret. Livmodhalsprogrammet. Årsrapport 2015. [cited 2017 Jul 4]. Available from: https://www.kreftregisteret.no/Generelt/Publikasjoner/Livmorhalsprogrammet/arsrapporter-fra-livmorhalsprogrammet/livmorhalsprogrammet-arsrapport-2015/ (in Norwegian).

- Retsinformation. [cited 2017 May 4]. Available from: http://www.retsinformation.dk/Forms/R0710.aspx?id=137127

- Ingemann-Hansen O, Lidang M, Niemann I, et al. Screening history of women with cervical cancer: a 6-year study in Aarhus, Denmark. Br J Cancer. 2008;98:1292–1294.

- Statistics Denmark. [cited 2017 May 4]. Available from:http://www.statistikbanken.dk/10021.

- Tranberg M, Larsen MB, Mikkelsen EM, et al. Impact of opportunistic testing in a systematic cervical cancer screening program: a nationwide registry study. BMC Publ Health. 2015;15:681. DOI 10.1186/s12889-015-2039-0.

- Lam JU, Rebolj M, Møller DE, et al. Human papillomavirus self-sampling for screening nonattenders: opt-in pilot implementation with electronic communication platforms. Int J Cancer. 2017;140:2212–2219.

- Tranberg M, Bech BH, Blaakær J, et al. Study protocol of the CHOiSE trial: a three-armed, randomized, controlled trial of home-based HPV self-sampling for non-participants in an organized cervical cancer screening program. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:835.

- Kristiansen BK, Andersen B, Bro F, Svanholm H, Vedsted P. Reminders to general practitioners, improve follow-up after cervical cytology: a Danish nationwide before-after natural experiment. Br J Gen Pract. 2017. DOI:10.3399/bjgp17X691913

- National Institute for Public Health and the Environment. http://www.rivm.nl/en/Topics/C/Cervical_cancer_screening_programme [cited 2017 May 4].

- Socialstyrelsen. [cited 2017 Mar 10]. Available from:http://cancercentrum.se/samverkan/vara-uppdrag/prevention-och-tidig-upptackt/gynekologisk-cellprovskontroll/vardprogram/

- Statens Serum Institute. [cited 2017 May 4]. Available from: http://www.ssi.dk/Smitteberedskab/Sygdomsovervaagning/VaccinationSurveillance.aspx?xaxis=Cohort&vaccination=6&sex =0&landsdel=100&show=&datatype=Vaccination&extendedfilters=True#HeaderText