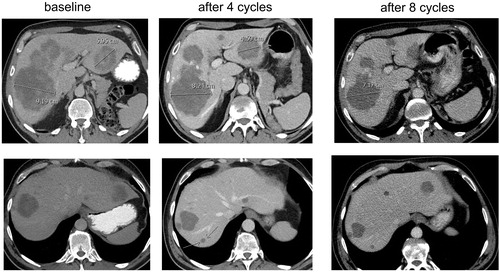

For several years, it is known that classic RECIST criteria are suboptimal to evaluate cancer treatment with targeted and immunomodulatory agents, for instance because these criteria underestimate the clinical value of prolonged disease stabilizations [Citation1]. More recently, this topic was much debated in efforts to explain the unexpected results of the FIRE-3 trial, which showed a benefit in overall survival for treatment with FOLFIRI + cetuximab compared with FOLFIRI + bevacizumab in patients with KRAS wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer, despite the fact that results on progression-free survival and response rates were highly comparable [Citation2]. Although this finding was not confirmed in a larger trial with similar design (CALGB 80405) [Citation3], early tumor shrinkage (ETS) and depth of response have been suggested as anti-EGFR antibody treatment-related tumor dynamics that are not captured by classic RECIST criteria and which may explain the results of FIRE-3 [Citation4,Citation5]. The results of FIRE-3 have had a significant impact on recent analyses on the predictive role of primary tumor location for the systemic treatment of metastases with chemotherapy plus either anti-EGFR or anti-VEGF antibodies [Citation6,Citation7]. However, anti-VEGF antibody treatment may also be associated with specific tumor dynamics. Patients with metastatic colorectal cancer treated with chemotherapy plus bevacizumab may have a morphological response, which is defined as metastases changing from heterogeneous masses with ill-defined margins into homogeneous hypo-attenuating lesions with sharp borders [Citation8,Citation9]. CT scan-based morphological response criteria were shown to have a statistically significant association with pathologic response (fibrosis) and overall survival, and much better predicted outcome compared with classic RECIST response criteria [Citation8]. This is due to the fact that RECIST criteria only capture volumetric changes, and patients with RECIST disease stabilization with a morphological response probably have a better outcome than without morphological response. In addition, we here provide data showing that evaluation of chemotherapy + bevacizumab in colorectal cancer liver metastases by RECIST criteria may also incorrectly evaluate patients as having disease progression while in fact they are responding. A 56-year-old male was diagnosed with a cT3N1M1 adenocarcinoma of the rectum with unresectable liver metastases. He was treated with short-course radiation on his primary tumor, and was included in the CAIRO5 study [Citation10], in which patients are being randomized between the currently most optimal systemic induction regimens depending on the BRAF/RAS mutation status of the tumor. He was allocated to treatment with FOLFOXIRI + bevacizumab, and after four cycles, he reported an improvement in his clinical condition with less fatigue compared to baseline. His laboratory values at baseline and after four and eight cycles were as follows: serum CEA 402, 247 and 34 µg/L (upper limit of normal, ULN 5.5), LDH 626, 190 and 232 U/L (ULN 248), alkaline phosphatase 667, 239 and 182 U/L (ULN 120), and gamma-GT 626, 203 and 148 U/L (ULN 60), respectively. Serum bilirubin and transaminase levels remained normal. A CT scan after four cycles showed a reduction in size as well as a morphological response of liver metastases (). However a new lesion was detected in segment 7, which also in retrospect was not visible at baseline and according to RECIST criteria should, therefore, be evaluated as progression of disease. Given the improvement in clinical condition as well as in relevant laboratory parameters as well as the radiological response in the majority of liver metastases, we postulated that this new lesion may have been preexisting, but had become better visible on CT scan due to morphological changes. Therefore we continued with the same systemic regimen. After eight cycles patient remained in good clinical condition, the laboratory parameters continued to improve, and a CT scan confirmed an ongoing radiological response with no increase of the ‘new’ lesion in segment 7. Although a mixed response could initially not be completely ruled out, the fact that patient is in ongoing remission for 12 months on first-line treatment strongly argues against this possibility. We conclude that the use of RECIST criteria in the evaluation of patients with colorectal cancer liver metastases treated with chemotherapy plus bevacizumab may inappropriately classify patients as having progressive disease (pseudo-progression). This phenomenon may result in the incorrect discontinuation of an effective treatment, which subsequently compromises patient survival and negatively impacts the survival outcome of patients treated with anti-VEGF antibodies in clinical trials. Updated criteria for response evaluation are urgently warranted.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Sleijfer S, Wagner AJ. The challenge of choosing appropriate end points in single-arm phase II studies of rare diseases. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:896–898.

- Heinemann V, von Weikersthal LF, Decker T, et al. FOLFIRI plus cetuximab versus FOLFIRI plus bevacizumab as first-line treatment for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer (FIRE-3): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:1065–1075.

- Venook A, Niedzwiecki D, Lenz H, et al. CALGB/SWOG 80405: phase III trial of irinotecan/5-FU/leucovorin (FOLFIRI) or oxaliplatin/5-FU/leucovorin (mFOLFOX6) with bevacizumab (BV) or cetuximab (CET) for patients (pts) with KRAS wild-type (wt) untreated metastatic adenocarcinoma of the colon or rectum (MCRC). J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(Suppl): Abstract LBA3.

- Stintzing S, Modest DP, Rossius L, et al. FOLFIRI plus cetuximab versus FOLFIRI plus bevacizumab for metastatic colorectal cancer (FIRE-3): a post-hoc analysis of tumour dynamics in the final RAS wild-type subgroup of this randomised open-label phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:1426–1434.

- Venook AP, Tabernero J. Progression-free survival: helpful biomarker or clinically meaningless end point? J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:4–6.

- Tejpar S, Stintzing S, Ciardiello F, et al. Prognostic and predictive relevance of primary tumor location in patients with RAS wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer: retrospective analyses of the CRYSTAL and FIRE-3 trials. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:194–201.

- Holch JW, Ricard I, Stintzing S, et al. The relevance of primary tumour location in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: A meta-analysis of first-line clinical trials. Eur J Cancer. 2017;70:87–98.

- Chun YS, Vauthey JN, Boonsirikamchai P, et al. Association of computed tomography morphologic criteria with pathologic response and survival in patients treated with bevacizumab for colorectal liver metastases. JAMA. 2009;302:2338–2344.

- Shindoh J, Loyer EM, Kopetz S, et al. Optimal morphologic response to preoperative chemotherapy: an alternate outcome end point before resection of hepatic colorectal metastases. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:4566–4572.

- Huiskens J, van Gulik TM, van Lienden KP, et al. Treatment strategies in colorectal cancer patients with initially unresectable liver-only metastases, a study protocol of the randomised phase 3 CAIRO5 study of the Dutch Colorectal Cancer Group (DCCG). BMC Cancer. 2015;15:365.