Abstract

Background: Multidisciplinary team meetings (MDTMs) have developed into standard of care to provide expert opinion and to grant evidence-based recommendations on diagnostics and treatment of cancer. Though MDTMs are associated with a range of benefits, a growing number of cases, complex case discussion and an increasing number of participants raise questions on cost versus benefit. We aimed to determine cost of MDTMs and to define determinants hereof based on observations in Swedish cancer care.

Methods: Data were collected through observations of 50 MDTMs and from questionnaire data from 206 health professionals that participated in these meetings.

Results: The MDTMs lasted mean 0.88 h and managed mean 12.6 cases with mean 4.2 min per case. Participants were mean 8.2 physicians and 2.9 nurses/other health professionals. Besides the number of cases discussed, meeting duration was also influenced by cancer diagnosis, hospital type and use of video facilities. When preparatory work, participation and post-MDTM work were considered, physicians spent mean 4.1 h per meeting. The cost per case discussion was mean 212 (range 91–595) EUR and the cost per MDTM was mean 2675 (range 1439–4070) EUR.

Conclusions: We identify considerable variability in resource use for MDTMs in cancer care and demonstrate that 84% of the total cost is derived from physician time. The variability demonstrated underscores the need for regular and structured evaluations to ensure cost effective MDTM services.

Introduction

Treatment recommendations from multidisciplinary team meetings (MDTMs) have developed into standard of care in cancer diagnostics and management. Based on case reviews and multidisciplinary and multi-professional discussions, evidence-based recommendations and expert opinion on diagnostics and treatment are provided. This principle has been shown to increase adherence to guidelines and to be associated with better quality of care [Citation1–4]. From the patient’s perspective, MDTMs grant multidisciplinary evaluations and up-to-date treatment recommendations, may contribute to equality in care and represent a relevant time point to consider possibilities for treatment within clinical trials. Most MDTMs are run on a weekly basis and may be local, hospital-based, or regional, video-based to allow for participation from health professionals in a larger geographical area.

Guidelines for selection of cases for MDTM discussions differ between hospitals and cancer types with two main formats, i.e., brief discussions of all cases or in-depth discussions of select complex cases. In the UK, the fraction of cancer patients managed at MDTMs has increased from 20 to 80% during the latest decades [Citation5]. In Sweden, the first MDTMs for e.g., breast cancer, head and neck cancer and sarcoma were initiated in the 1980’s. Today, most cancer types are covered by an MDTM and the growing fraction of patients managed at MDTMs are monitored in the national quality registers for cancer. In 2009, 92% of breast cancer patients, 89% of head and neck cancer patients, 79% of rectal cancer patients, 50% of lung cancer patients and 32% of colon cancer patients were discussed at MDTMs [Citation6]. In 2016, these frequencies were 75% for lung cancer and 98–99% for the other cancer types, whereas selected case discussions apply in e.g., urologic and gynecologic cancer [Citation7].

The MDTMs have evolved from inter disciplinary meetings attended by a limited number of physicians e.g., in medical oncology, radiation therapy, surgery, radiology and pathology, into organ-based meetings with participation from a large number of multi-professional experts, e.g., specialized surgery, nuclear medicine, supportive and palliative care and rehabilitation. A growing number of professions also participate with e.g., physiotherapists, cancer nurses, dieticians, occupational therapists, research nurses and MDTM coordinators frequently being members of the MDTM team [Citation8,Citation9].

An increasing cancer incidence, more complex diagnostic procedures and therapeutic options and a growing number of MDTMs and participants contribute to increased use of resouces and raise issues of the cost-effectiveness of MDTMs. A potential beneficial effect from MDTM on the cost of cancer care remains to be defined since studies hereof have reached different conclusions [Citation1,Citation4]. We estimated MDTM cost and determinants hereof based on observations of all 50 cancer-related MDTMs in the south Sweden health care region and time estimates from participants in these MDTMs.

Material and methods

Annually, 13,000 patients are diagnosed with cancer in the south Sweden health care region with a population of 1.8 million [Citation10]. Specialized cancer services are provided by one university hospital and six county hospitals with a total of 50 weekly cancer-related MDTMs available. Of these, 22 are provided by the university hospital and 28 are held at county hospitals. Facilities for video-based meetings are available at 13 and 11 of these MDTMs, respectively. The MDTMs cover all malignant diagnoses except for lymphoma and hematologic cancers for which inter-professional case reviews rather than full MDTM services have been implemented. The 50 MDTMs were dedicated to breast cancer and malignant melanoma (n = 16), upper gastrointestinal cancer (including esophageal cancer, gastric cancer, hepatobiliary cancer and pancreatic cancer) (n = 9), lung cancer (n = 8), colorectal cancer (n = 5), urologic cancer (prostate cancer, renal cell cancer and urothelial cancer) (n = 5), head and neck cancer (n = 2), gynecologic cancer (n = 1), sarcoma (n = 1), endocrine tumors (n = 1), CNS tumors (n = 1) and penile cancer (n = 1). The university hospital-based MDTM for penile cancer constitutes a national conference with video-based participation from all six university hospitals in Sweden, but the evaluation hereof considered only the regional resources.

This observation study used a standardized evaluation scheme to collect data on meeting structure, number of cases discussed and attendance from various health professionals and disciplines. Each of the 50 MDTMs was observed once by one or two research group members between February and July 2016. Participation time was recorded for each health professional, including the time that each local hospital was connected to video-based MDTMs. In the analyzes nurses and other personell, e.g., coordinators, physiotherapists and medical secretaries, were grouped.

Since MDTM services, besides direct participation, also requires preparation and post-MDTM administrative work, we collected time estimates from the participants based on an electronic survey that also contained questions on benefits and barriers from MDTMs (data not shown). The time estimates provided were rounded up to the closest 0.25 h.

Calculations of cost applied standardized wages from Statistics Sweden [Citation11], with monthly wages of 3696 EUR (21.5 EUR/h) for nurses and coordinators and 7634 EUR (44.4 EUR/h) for physicians using a standard of 172 working hours per month. Social security costs and payroll taxes of 48.82% were added to salary costs. For cost estimates in relation to hospital type and use of video facilities, the mean participation time for physicians and nurses was used. We did not accounts for facility costs, except for a user fee of 826 EUR/month for video-conferencing systems. The nine MDTM rooms equipped with video facilities were weekly used for 14 MDTMs, which translated to an additional cost of 531 EUR per video-based MDTM. Costs were calculated in relation to participants, disciplines, hospital types, use of video-based meetings and cancer diagnoses. Currency conversion from SEK to EUR was based on the 2016 average exchange rate of 9.4704 from the Central Bank of Sweden.

All statistical analyzes were performed in R, version 3.2.2 [Citation12]. A variance model was employed to investigate the impact from potential predictors on the duration of the meetings using log transformed data. A statistical significance level of 5% was used and no adjustment for multiplicity was performed. The duration of the MDTMs in relation to the number of cases discussed was depicted as bubble plots for different types of MDTMs. The time used for preparation, participation and post-MDTM work in relation to discipline and profession were depicted as box plots designated by quartiles. Differences in mean times for preparation, participation and post-MDTM work were analyzed using one-way analysis of varaiance (ANOVA). The study was granted ethical permission (# 2016/195) from the Lund University ethics committee.

Results

The 50 MDTMs showed considerable variability in format, number of case discussions and participants. Total participants included 393 physicians, 105 nurses and 29 other professionals. Radiologists participated in 96% of the meetings and pathologists in 88%, though pathology pictures were demonstrated only in 34% of the meetings. Of the 50 meetings, MDTM coordinators were present in 40%. The principles for case discussion differed between diagnoses; in eight cancer types, all newly diagnosed patients were managed through MDTMs, whereas select cases were discussed in lung cancer, melanoma, urologic cancer and gynecologic cancer (). All MDTMs had a defined list of cases for review, but only a few MDTM teams used standardized case presentations. Direct documentation of recommendations through dictation occurred in 30% of the meetings.

Table 1. Characteristics of the 50 MDTMs.

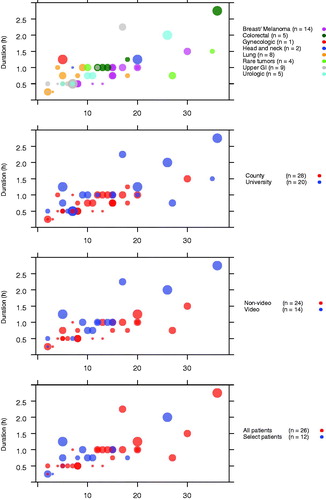

Based on our observations, an MDTM lasted mean 0.88 (range 0.25–2.75) h and managed mean 12.6 (range 2–36) cases with participation from mean 8.2 (2–16) physicians and 2.9 (0–6) nurses/others (). The total time per case discussion, considering all participants, ranged from 0.29 to 2.32 h for physicians and from 0.01 to 0.5 h for nurses/others. The mean time per case discussion was 4.2 min with variability from 1.8 min for sarcoma to 9.6 min for the gynecologic cancer. MDTMs at the university hospital discussed mean 14.6 cases and lasted mean 1.06 (0.5–2.75) h compared to mean 11.1 cases and 0.74 (0.25–1.5) h at the county hospitals, resulting in mean times per case of 4.4 and 4.0 min, respectively. Participating physicians and nurses/others were mean 10.1 and 3.0 at the university hospital and mean 6.8 and 2.8 at the county hospitals, respectively. Video-based MDTMs (n = 14) lasted mean 1.14 (0.25–2.75) h, whereas non-video based MDTMs (n = 26) lasted mean 0.76 (0.25–1.25) h with mean 12.7 cases discussed in both formats. MDTM duration correlated with the number of case discussions, but was also significantly influenced by cancer type (p = .005), local hospital versus university hospital (p = .038), video-based versus non-video based meetings (p = .002), but not to discussion of all versus select patients (p = .455) ().

Figure 1. Bubble plots depicting MDTM length in relation to the number of case discussions. The diameter of each circle is proportional to the number of participants with the smallest equal to 2 and the largest equal to 22 participants. The plots demonstrate MDTM cases and length relative to (a) diagnosis (p = .005), (b) local versus university hospital-based meetings (p = .038), (c) video-based versus local meetings (p = .002) and (d) dissussion of all versus select patients (p = .455).

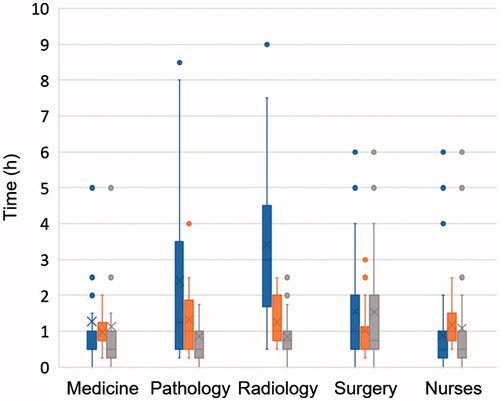

Data on time for preparation, participation and post-MDTM administrative work was reported from 206/362 (57%) invited participants. Physicians (n = 155) reported mean times of 1.84 h for preparation, 1.07 h for participation and 1.23 h for post-MDTM administrative work per MDTM. Nurses/others (n = 51) reported mean 0.89 h for preparation, 1.17 h for participation and 1.08 h for administrative post-MDTM work. The time required for preparation was reported to be significantly longer for pathologists, mean 2.4 h (p = .03) and radiologists, mean 3.4 h (p < .001) compared to internists with median 1.27 h and finally physicians in surgery who reported mean times of 1.55 h ().

Figure 2. Box plots showing estimated time per MDTM for preparation (blue), participation (orange) and post-MDTM administrative work (grey) in relation to speciality for physicians in surgery, medicine including oncology, radiology, pathology and to profession for nurses. In the boxes, mean times are marked with ‘x’ and median times with ‘–’.

MDTM costs were calculated using the combined data from our observations at the 50 MDTMs and the times reported by the 206 participants (). Time estimates for MDTM participation (excluding preparation and post-MDTM work) were somewhat higher from professionals’ estimates than from our observations ( and ), but had a minor impact on the cost estimates (mean 96.98, range 32–245, EUR/case, based on our observations compared to 101.94, range 41–214, EUR/case, based on participants’ reports). The total MDTM costs ranged from 1439 EUR for breast cancer and malignant melanoma to 4770 EUR for head and neck cancer with a mean cost of 2675 EUR (). The cost per case ranged from 91 EUR for breast cancer to 595 EUR for gynecologic cancer with a mean cost of 212 EUR (). Differences in cost per case discussion were were identified in relation to hospital type (225 EUR/case at the university hospital compared to 202 EUR/case in county hospitals), discussion of select cases versus all cases (318 EUR/case compared to 192 EUR/case) and use of video equipment (273 EUR/case for video-based meetings versus 169 EUR/case for local meetings) (). Overall, 84% of the cost was attributed to physician costs ().

Table 2. Estimated MSTM time and cost (in EUR).

Discussion

In cancer care, MDTMs represent an important possibility for case review and expert opinion. Based on observations and time estimates from cancer-related MDTM in Swedish health care we demonstrate that mean 8.2 physicians and 2.9 nurses–coordinators participate in the MDTMs, which is in line with data from UK on 6–10 participating physicians [Citation13]. The number of case discussions, mean 12.6 (range 2–36), the length of the meetings, mean 0.88 h, and the time per case discussion, mean 4.2 min. were also comparable to observations from UK with 14–35 case discussions, MDTM lengths of 1–2.5 h and case discussions of 4–7 min [Citation13,Citation14]. MDTM length naturally correlates with the number of case discussions, but also other factors such as cancer type, hospital type, use of video facilities influence MDTM length ().

In Sweden, the number of video-based MDTMs has increased during recent years linked to refined diagnostics and advanced treatment options, centralized treatment of rare cancers and an increased awareness of the need for equal treatment recommendations throughout the health care regions. The higher total cost for video-based MDTMs (273 EUR/case versus 169 EUR/case) should be viewed in relation to the reduced time for transport to/from physical meetings and the quality improvement from first-hand information from physicians who have responsibility for the patient at local hospitals who can participate in the video-based MDTM format. Video-based MDTMs may also contribute to the development of a shared culture and common understanding of cancer pathways through application of the same protocol and peer-review principles among specialists in different local teams within a geographical area.

Work to prepare, participate and administer MDTMs discussions and recommendations constitutes a major part of health professionals’ weekly duties. Indeed, the direct MDTM participation accounted for only 26% of the weekly time physicians spent on MDTM work and for 37% of the time reported by nurses. Preparation time was considerably longer for pathologists (2.4 h) and radiologists (3.4 h) () and is supported by similar estimates of 2.4–4 h for pathologists and 2–4.75 h for radiologists from UK and Ireland [Citation14–16]. Though MDTM preparation significantly impacts the work schedule in these disciplines, independent case review also represents an important safety aspect related to clinical responsibilities.

The MDTM cost per case was mean 212 EUR with a range from 91 to 595 EUR. The highest costs applied to video-based meetings and MDTMs that considered select complex cases (). Data based on professionals’ estimates resulted in slightly higher costs than the observations, which could potentially relate to the professionals considering time for transportation, which the observations did not take into account. Direct participation costs were estimated at mean 54.3 EUR, which is comparable to the cost of 44.7 EUR per case discussion reported from UK [Citation17]. Data from UK on MDTMs for breast cancer and head and neck cancer estimated case discussion costs of 59.9 EUR for breast cancer and 120.7 EUR for head and neck cancer, which can be compared to our estimates of 85 EUR for breast cancer and 353 EUR and for head and neck cancer [Citation14]. We estimate that 84% of the total costs were related to physician cost, which suggests that work to grant efficient MDTM performance need to define key experts and consider possibilities to avoid redundant expert participation.

The different MDTM formats with discussion of all cases versus select cases did not significantly influence MDTM length (), but were naturally associated with higher costs per case with mean 192 EUR versus mean 318 EUR per case (). Case discussions at MDTMs have been shown to change the initial treatment plan in one-third of cases. This, however, applies particularly to complex cases and recurrencies, whereas it is rare in standard cases [Citation18–20]. Studies using time-driven, activity-based costing has shown that improved quality of care leads to financial savings [Citation21], emphasizing the need for continous quality improvements. In many countries, including Sweden, structured evaluations of MDTMs remain to be developed. Regular evaluations are needed to develop MDTM services and to optimize use of resources [Citation4]. Performance measures could include principles for MDTM referral, structured case presentations, formalized peer review and documentation, evaluations of leadership and monitoring of adherence to guidelines and implementation of recommendations [Citation2,Citation3,Citation22].

Study limitations include observation of each MDTM at one occasion and consideration only of costs for staff and video facilities, though non-staff costs have been estimated to represent 9–14% of the total [Citation14]. Moreover, we can not evaluate a potential impact from e.g., standardized case presentations and direct dictation since this was infrequently used. Strengths of our study include observations of all MDTMs in a geographical area with 1.8 million inhabitants with cancer care performed at one university hospital and several regional hospitals and possibilities to perform subgroup analyzes relaed to e.g., diagnosis, profession, discipline, case discussion format and hospital type.

In summary, we demonstrate considerable variability of the cost per case discussion, from 85 to 519 EUR, in cancer-related MDTMs. Several factors, beyond the number of case discussions and meeting participants, i.e., diagnosis, use of video-conferencing systems and hospital type, influenced MDTM duration and cost. A well-functioning MDTM requires participation from qualified and effective experts and an optimized function related to e.g., format, structure, case selection and presentation, review, leadership and interaction between the participants [Citation9]. To meet future challenges in cancer care, work to optimize and evaluate MDTM services should be prioritized to ensure cost-effectiveness of this focal point of the diagnostic pathway.

Acknowledgments

MDTM technician Mats Palm is acknowledged for information on costs of video facilities. Cancer coordinators Tina Eriksson and Jeanette Törnquist are acknowledged for help in collecting data at MDTMs. Statisticians Stefan Peterson and Oskar Hagberg are acknowledged for statistical support.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Freeman RK, Ascioti AJ, Dake M, et al. The effects of a multidisciplinary care conference on the quality and cost of care for lung cancer patients. Ann Thorac Surg. 2015;100:1834–1838, discussion 8.

- Prades J, Remue E, van Hoof E, et al. Is it worth reorganising cancer services on the basis of multidisciplinary teams (MDTs)? A systematic review of the objectives and organisation of MDTs and their impact on patient outcomes. Health Policy. 2015;119:464–474.

- Raine R, Wallace I, Nic a’Bhaird C, et al. Improving the effectiveness of multidisciplinary team meetings for patients with chronic diseases: a prospective observational study. Health Serv Delivery Res. 2014;2:37.

- Taplin SH, Weaver S, Salas E, et al. Reviewing cancer care team effectiveness. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11:239–246.

- Fleissig A, Jenkins V, Catt S, et al. Multidisciplinary teams in cancer care: are they effective in the UK? Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:935–943.

- The National Board of Health and Welfare, Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions. Comparisons of cancer care quality and efficiency. March 15, 2012.

- [Internet]. http://www.cancercentrum.se/samverkan/vara-uppdrag/kunskapsstyrning/kvalitetsregister/.

- Fennell ML, Prabhu Das I, Clauser S, et al. The organization of multidisciplinary care teams: modeling internal and external influences on cancer care quality. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2010;2010:72–80.

- Lamb B, Green JS, Vincent C, et al. Decision making in surgical oncology. Surg Oncol. 2011;20:163–168.

- Official Statistics of Sweden. Cancer incidence in Sweden 2015. Stockholm: Official Statistics of Sweden; 2017.

- Database of wages [Internet]. Stockholm: Statistics Sweden; 2015. Available from: http://www.scb.se/.

- R Development Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2015.

- Restivo L, Apostolidis T, Bouhnik AD, et al. Patients’ non-medical characteristics contribute to collective medical decision-making at multidisciplinary oncological team meetings. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0154969.

- Simcock R, Heaford A. Costs of multidisciplinary teams in cancer are small in relation to benefits. BMJ. 2012;344:e2718.

- Kane B, Luz S, O’Briain DS, et al. Multidisciplinary team meetings and their impact on workflow in radiology and pathology departments. BMC Med. 2007;5:14.

- Taylor C, Munro AJ, Glynne-Jones R, et al. Multidisciplinary team working in cancer: what is the evidence? BMJ. 2010;340:c951.

- Fosker CJ, Dodwell D. The cost of the MDT. BMJ. 2010;340:c951.

- Oxenberg J, Papenfuss W, Esemuede I, et al. Multidisciplinary cancer conferences for gastrointestinal malignancies result in measureable treatment changes: a prospective study of 149 consecutive patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:1533–1539.

- Ryan J, Faragher I. Not all patients need to be discussed in a colorectal cancer MDT meeting. Colorectal Dis. 2014;16:520–526.

- Rao K, Manya K, Azad A, et al. Uro-oncology multidisciplinary meetings at an Australian tertiary referral centre–impact on clinical decision-making and implications for patient inclusion. BJU Int. 2014;114(Suppl. 1):50–54.

- Govaert JA, van Dijk WA, Fiocco M, et al. Nationwide outcomes measurement in colorectal cancer surgery: improving quality and reducing costs. J Am Coll Surg. 2016;222:19–29.e2.

- Trotman J, Trinh J, Kwan YL, et al. Formalising multidisciplinary peer review: developing a hematological malignancy-specific electronic proforma and standard operating procedureto facilitate procedural efficacy and evidence-based clinical practice. Intern Med J. 2017;47:542–548.