Abstract

Background: Since 40 years, Danish Breast Cancer Cooperative Group (DBCG) has provided comprehensive guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer. This population-based analysis aimed to describe the plurality of modifications introduced over the past 10 years in the national Danish guidelines for the management of early breast cancer. By use of the clinical DBCG database we analyze the effectiveness of the implementation of guideline revisions in Denmark.

Methods: From the DBCG guidelines we extracted modifications introduced in 2007–2016 and selected examples regarding surgery, radiotherapy (RT) and systemic treatment. We assessed introduction of modifications from release on the DBCG webpage to change in clinical practice using the DBCG clinical database.

Results: Over a 10-year period data from 48,772 patients newly diagnosed with malignant breast tumors were entered into DBCG’s clinical database and 42,197 of these patients were diagnosed with an invasive carcinoma following breast conserving surgery (BCS) or mastectomy. More than twenty modifications were introduced in the guidelines. Implementations, based on prospectively collected data, varied widely; exemplified with around one quarter of the patients not treated according to a specific guideline within one year from the introduction, to an almost immediate full implantation.

Conclusions: Modifications of the DBCG guidelines were generally well implemented, but the time to full implementation varied from less than one year up to around five years. Our data is registry based and does not allow a closer analysis of the causes for delay in implementation of guideline modifications.

Introduction

In 1977 the Danish Breast Cancer Cooperative Group (DBCG) launched a nationwide breast cancer database accompanying multidisciplinary guidelines for diagnostic, treatment and follow-up of breast cancer [Citation1,Citation2]. These initiatives have improved the quality of diagnostic procedures and all aspects of breast cancer treatment in Denmark. Furthermore, continued development and standardization of procedure and treatment strategies have significantly contributed to an improvement of the prognosis in breast cancer and has become a model for the construction of multidisciplinary cancer groups [Citation3,Citation4]. Improvement in the quality of care by clinical guidelines has been shown repeatedly but it is less clear how effectively guidelines are maintained and how long time it takes to implement modifications [Citation5].

Several potential barriers may delay implementation of evidence-based guidelines but the awareness of guidelines from the DBCG is promoted by the involvement of relevant professionals, a joint conception of the guidelines and a clinical database and a quality ensurance system [Citation6]. Partnerships between those who produce guidelines and those who use them are likely to enhance their relevance and implementation, and the guidelines of the DBCG, therefore, have been authored by scientific committees encountering all breast centers in Denmark [Citation7].

Methods

Study population

Since 2006, all patients with a record of a first invasive breast tumor in the Danish National Pathology Registry have been registered in the clinical database of DBCG.

Guidelines

National guidelines are continuously modified and available from the website of DBCG (www.dbcg.dk). The guidelines are prepared and agreed upon in the Scientific Committee of each of the specialties. All Danish centers are represented in the committees. The guidelines are finally approved by the DBCG board.

Organization of the database

The clinical DBCG database comprises a web-based open source data entry and display module with pages adapted for each of the specialties involved. Remote data entry is accessible from all Danish hospital units involved in diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer patients. The modules encompass data validation on data entry and cross validations connected queries directed to specific departments. The database and query system is updated on a daily basis. Treatment guideline algorithms based on reported data on patient characteristics and prognostic factors are built into the system. The data entry and query system has been extended to non-Danish centers participating in randomized DBCG clinical trials.

Histopathology

The reported histopathological data included histological type according to WHO [Citation8], tumor size, examination of tumor margins, invasion into skin or deep resection line, malignancy grade, number of nodes examined, hereof tumor positive, vascular invasion, estrogen (ER) and/or progesterone status, HER2 status, TOP2A status (2007–2013) and Ki67 (from 2009). Additional analysis and definitions are described in details elsewhere [Citation3,Citation9].

Treatment

The data of therapeutic interventions included type of breast (mastectomy or breast conserving surgery (BCS)) and axillary (sentinel node (SN) or axillary lymph node dissection (ALND)) surgery, oncoplastic procedures, radiotherapy (RT) (target, dose, number of fractions), systemic therapy (type, doses, duration), hematological toxicities and other adverse events and the results of the follow-up studies.

Supplementary data

Each patient is registered with a unique civic registration number assigned to each citizen in Denmark [Citation10]. Through linkage to nationwide Danish health registries, complete and continuously updated data on vital status and emigration (Danish Civil Registration System), cause of death (Danish Causes of Death Registry), pathology reports (National Pathology Registry), other malignancy (Danish Cancer Registry) and hospitalizations (National Patient Registry) are retrieved. From the National Patient Registry data, an algorithm has been set up to assign a Charlson comorbidity index to each registered patient [Citation11].

Results

From 2007 to 2016 records from 48,772 patients with malignant breast tumors was entered into DBCG’s clinical database, and 42,197 of these patients were diagnosed with an invasive carcinoma following BCS or mastectomy.

Risk assessment

From 1977 to 1989 patients were classified as high-risk if node-positive, tumor size >5 cm or tumor invasion in skin or deep fascia or otherwise as low-risk [Citation7]. The high-risk group was gradually extended and in 2013 a prognostic model was introduced to allow de-escalation of chemotherapy among postmenopausal patients with ER positive breast cancers. This model was constructed using prospectively recorded data on recurrence and survival from 6529 patients who in 1996–2004 as the sole adjuvant systemic treatment received tamoxifen, an aromatase inhibitor or the two in sequence. Using multivariable fractional polynomials a highly performing prognostic index was constructed [Citation12]. In 2017, risk assessment was further refined by inclusion of molecular subtypes (PAM50) [Citation13].

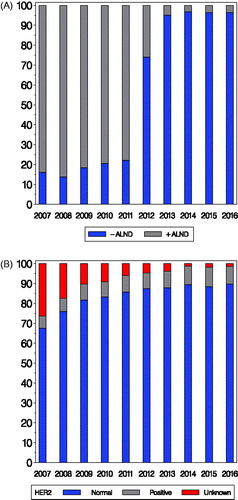

Surgery

Since 2002 the preferred surgical procedure has been BCS combined with SN assessment, and more than 70% of the patients with invasive breast cancer received a BCS in 2016. Guidelines for surgical margin was changed in 2013, see Supplementary Table 1 [Citation14]. ALND is limited to node positive cases and cases not eligible for the SN technique. Primarily based on the results from the ACOSOG Z0011 trial DBCG guidelines () for ALND following SN was changed in December 2011 [Citation15]. shows the distribution of axillary surgery in patients with micrometastases only in SN. Omission of ALND increased slowly from 16% in 2007 to 21% in 2010, before the guideline was changed in December 2011, rose to 74% after adoption of the revised guideline and ALND was omitted in around 95% from 2013 to 2016.

Figure 1. Panel A: Distribution in percent of use of ALND according to year of surgery for patients with invasive breast cancer with micrometastases only in SN (N = 4869 for the period 2007–2016). Panel B: Distribution in percent of HER2 status according to year of surgery for patients with ER positive disease 60 years or older at diagnosis (N = 22,209).

Table 1. Changes 2007–2016 in guidelines selected for data presentation.

Pathology

HER2 assessment was in Denmark introduced for identification of eligible participants to the HERceptin Adjuvant (HERA) trial [Citation16,Citation17]. As a results from HERA and other adjuvant trastuzumab trials HER2 assessment was in 2005 introduced to a restricted population and the guidelines were revised in 2008 () and has since April 2010 been a standard prognostic and predictive factor comprising all breast cancer patients [Citation18,Citation19]. The change introduced April 2010 in guidelines for adjuvant therapy included patients 60 years or older with ER and HER2 positive breast cancer, and shifted from endocrine therapy alone to combined treatment with chemotherapy, trastuzumab and an aromatase inhibitor. shows the distribution of HER2 status according to year of inclusion for this subgroup of patients. The proportion of patients registered with HER2 status increased from 74% in 2007 to 94% in 2011 and 99% in 2016.

ER is registered as a continuous variable allowing for use of different cut-points [Citation20,Citation21]. Very few patients are registered with ER 1–9% (approximately 65 patients per year). Ki67 has been assessed for most patients since 2009, but was not introduced in treatment guidelines (Supplementary Table 2) due to lack of standardization (methodology, reproducibility) [Citation22].

Radiotherapy

Since 1999 postoperative RT has been recommended following BCS and following mastectomy if node positive (macrometastasis) to women less than 70 years. The age criterion was modified in 2008, Supplementary Table 3. In patients ≥75 years the treatment has been based on an individual evaluation, with a high focus on patient shared decision making.

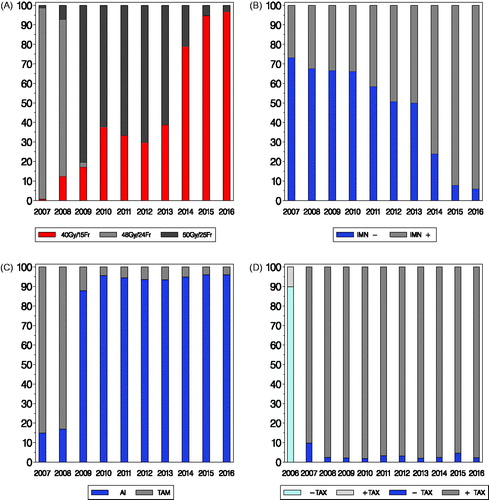

The fractionation schedules have been changed several times during the last decade, . shows the distribution of different schemes according to time of RT for patients with invasive breast cancer, who had breast only RT and not included in a randomized trial. A marked change from 98 to 81% treated with 48 Gy/24 fractions (Fr) in 2007 and 2008 to 2% in 2009 was seen following the change in guideline January 2009, where the DBCG recommendation was modified to 50 Gy/25 Fr to ensure comparability with other countries. Hypofractionation based on 40 Gy/15 Fr was partly introduced for selected patients treated with breast only RT in the guidelines in 2010, but implemented earlier (1% in 2007, 13% in 2008). In 2014 and 2016 the corresponding figures were 79 and 97%.The division in the years 2009–2015 is a result of successively implementation for different patient groups, but also a different approach in different centers.

Figure 2. Panel A: Distribution in percent of fractionation used for invasive breast cancer patients with breast only radiation therapy according to year of radiation (N = 15,005; patients in RT trials not included). Panel B: Distribution in percent of inclusion of IMN (internal mammary nodes) according to year of radiation for patients with loco-regional radiotherapy and left-sided breast cancer (N = 5805). Panel C: Distribution in percent of up-front treatment with either tamoxifen (TAM) or an aromatase inhibitor (AI) according to year of inclusion for postmenopausal patients allocated to endocrine treatment (N = 17,314; patients in trials for systemic treatment not included). Panel D: Distribution in percent of high-risk patients allocated to chemotherapy according to year of inclusion and whether chemotherapy was taxane based (N = 14,457).

From 2003 all high risk breast cancer patients treated with loco-regional RT had the internal mammary nodes (IMN) included in the RT fields in right sided breast cancer, but not in left sided. The IMN target generally included the nodes in caudal direction to the intercostal space IV. In 2014 all patients, irrespective of laterality, receiving loco-regional RT according to DBCG guideline had the IMN included [Citation23–25]. shows the proportion of node-positive patients with IMN included according to year of RT for left sided patients, with a marked change in 2014 (76% IMN included) and very few patients not having IMN in the target in 2016 (6%).

Systemic treatment

Systemic treatment is not recommended to postmenopausal women with T1 tumors in the absence of other risk factors [Citation26]. The group of patients receiving systemic treatment has gradually increased, Supplementary Table 4. In 2007 the recommended endocrine therapy was five years of tamoxifen in premenopausal and sequential tamoxifen-aromatase inhibitor in postmenopausal patients [Citation27]. Up-front letrozole to postmenopausal patients was recommended from January 2009 () [Citation28]. shows postmenopausal patients not included in randomized trial allocated to endocrine therapy according to up-front treatment and year of inclusion. From 16% with up-front AI before the guideline was applicable, the vast majority received an aromatase inhibitor up-front thereafter with 88% in 2009 and 96% in 2010 and 2016. Other changes concerning endocrine treatment are listed in Supplementary Table 4.

Adjuvant trastuzumab has since 2010 been recommended to all patients with HER2 overexpressing or amplified breast cancer. In the period 2006–2010 trastuzumab was only recommended to patients who also were recommended chemotherapy [Citation16]. The administration of trastuzumab has changed from weekly to three-weekly and from intravenous to subcutaneous administration. Also, pertuzumab in combination with trastuzumab has been introduced in the neoadjuvant setting [Citation29].

Throughout 2007–2016 the recommended adjuvant chemotherapy has been three-weekly cycles of EC (600, 90 mg/m2) followed by either three-weekly cycles of docetaxel (100 mg/m2) or nine weekly cycles of paclitaxel (80 mg/m2) [Citation30,Citation31]. shows the chemotherapy regimen with or without inclusion of a taxane for this time period. Also, 2006 has been listed to highlight the change by January 2007. In 2006 10% had taxane based CT, changing to 90% in 2007 and stabilizing thereafter with 98% in 2008 and 97% in 2016. The use of paclitaxel has gradually increased from none to the vast majority of patients. Neo-adjuvant chemotherapy has throughout the 10 year period been an option and has since 2016 been encouraged for patients with HER2 positive and to patients with ER and HER2 negative breast cancers. Zoledronic acid (eight times with six months intervals) has been recommended since 2014.

Discussion

In its fourth decade, the DBCG continued to refine multidisciplinary guidelines and further develop the comprehensive clinical database to allow an evaluation of the implementation of the guidelines. More than twenty revisions were introduced in 2007 through 2016 in the DBCG guidelines which reflect the high level of activity within this multidisciplinary group. The revisions monitored in this study were all successfully implemented within a reasonable short timeframe probably facilitated by easily assessable guidelines placed jointly with an online decision support system on the webpage of the responsible cooperative group. Accessibility and applicability has repeatedly been highlighted as the most important factors for implementation of guidelines [Citation32,Citation33].

This study in addition indicates that time from announcement of a breast cancer guideline revision until it is fully implemented may vary from less than one year to more than two years according to the type and setting of the treatment. Guideline revisions dealing with change of systemic treatment were implemented within less than a year while more than two years passed before revisions concerning loco-regional treatment were implemented. Also, treatment strategies were to some extent introduced before established in guidelines. There seem to have been the same degree of evidence behind all revision. Upfront treatment with an aromatase inhibitor instead of tamoxifen was based on results from the BIG 1–98 [Citation28], the decision to recommend the addition of a taxane to adjuvant chemotherapy was based on a systematic review [Citation31], omission of ALDN in patients with micrometastases only in SN was based on the ACOSOG Z0011 trial [Citation15] and the revision on irradiation of left-sided IMN was based on a large cohort study [Citation23]. In contrast, only the guideline revisions on systemic treatment were accompanied by a health technology assessment (HTA) to facilitate reimbursement [Citation34].

We are in this study able exactly to indicate the sequence of events. First, the introduction of revisions in the guidelines of the DBCG is announced on the DBCG website setting an official date for their introduction. Second, data prospectively documenting the degree of implementation could for each revision be extracted from the clinical DBCG database. In contrast, implementation of guidelines is frequently evaluated retrospectively using questionnaires [Citation35].

Some limitations should be considered when interpreting our study. We only monitored a small sample of revisions introduced in the last decade, and those included were better defined than those remaining. We did not assess comorbidity in this study and multimorbidity involves a variety of challenges and may to some degree have limited implementation [Citation36]. Further, regional differences have not been investigated.

In conclusion, the guidelines of the DBCG to a large extent ensures homogenous diagnostic and treatment strategy across all centers and implementation of guideline modifications is generally successful although time from introduction to implementation varies across the different disciplines.

Maj-Britt_Jensen_et_al._Supplementary_material.docx

Download MS Word (31.5 KB)Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflict of interest.

References

- Andersen KW, Mouridsen HT. Danish Breast Cancer Cooperative Group (DBCG). A description of the register of the nation-wide programme for primary breast cancer. Acta Oncol. 1988;27:627–647.

- Blichert-Toft M, Christiansen P, Mouridsen HT. Danish Breast Cancer Cooperative Group–DBCG: history, organization, and status of scientific achievements at 30-year anniversary. Acta Oncol. 2008;47:497–505.

- Mouridsen HT, Bjerre KD, Christiansen P, et al. Improvement of prognosis in breast cancer in Denmark 1977–2006, based on the nationwide reporting to the DBCG registry. Acta Oncol. 2008;47:525–536.

- Jensen MB, Ejlertsen B, Mouridsen HT, et al. Improvements in breast cancer survival between 1995 and 2012 in Denmark: the importance of earlier diagnosis and adjuvant treatment. Acta Oncol. 2016;55(2):24–35.

- Grimshaw JM, Russell IT. Effect of clinical guidelines on medical practice: a systematic review of rigorous evaluations. Lancet. 1993;342:1317–1322.

- Francke AL, Smit MC, de Veer AJ, et al. Factors influencing the implementation of clinical guidelines for health care professionals: a systematic meta-review. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2008;8:38.

- Møller S, Jensen MB, Ejlertsen B, et al. Danish Breast Cancer Cooperative Group. The clinical database and the treatment guidelines of the Danish Breast Cancer Cooperative Group (DBCG); its 30-years experience and future promise. Acta Oncol. 2008;47:506–524.

- Lakhani SR, Ellis IO, Schnitt SJ, et al. WHO classification of tumours of the breast. 4th ed. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2012.

- Kiaer HW, Laenkholm AV, Nielsen BB, et al. Classical pathological variables recorded in the Danish Breast Cancer Cooperative Group’s register 1978–2006. Acta Oncol. 2008;47:778–783.

- Schmidt M, Pedersen L, Sørensen HT. The Danish Civil Registration System as a tool in epidemiology. Eur J Epidemiol. 2014;29:541–549.

- Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–383.

- Ejlertsen B, Jensen MB, Mouridsen HT. Excess mortality in postmenopausal high-risk women who only receive adjuvant endocrine therapy for estrogen receptor positive breast cancer. Acta Oncol. 2014;53:174–185.

- Laenkholm AV, Jensen MB, Eriksen JO, et al. The PAM50 risk of recurrence score predicts 10 year distant recurrence in a comprehensive Danish cohort of 2558 postmenopausal women allocated to 5 year of endocrine therapy for hormone receptor positive early breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2018;57: in press.

- Houssami N, Macaskill P, Marinovich ML, et al. Meta-analysis of the impact of surgical margins on local recurrence in women with early-stage invasive breast cancer treated with breast-conserving therapy. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46:3219–3232.

- Giuliano AE, Hunt KK, Ballman KV, et al. Axillary dissection vs. no axillary dissection in women with invasive breast cancer and sentinel node metastasis a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2011;305:569–575.

- Piccart-Gebhart MJ, Procter M, Leyland-Jones B, et al. Herceptin Adjuvant (HERA) Trial Study Team. Trastuzumab after adjuvant chemotherapy in HER2-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1659–1672.

- Cameron D, Piccart-Gebhart MJ, Gelber RD, et al. Herceptin Adjuvant (HERA) Trial Study Team. 11 years’ follow-up of trastuzumab after adjuvant chemotherapy in HER2-positive early breast cancer: final analysis of the HERceptin Adjuvant (HERA) trial. Lancet. 2017;389:1195–1205.

- Wolff AC, Hammond ME, Schwartz JN, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists guideline recommendations for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 testing in breast cancer. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2007;131:18–43.

- Wolff AC, Hammond ME, Hicks DG, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology; College of American Pathologists. Recommendations for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 testing in breast cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3997–4013.

- Viale G, Regan MM, Maiorano E, et al. Prognostic and predictive value of centrally reviewed expression of estrogen and progesterone receptors in a randomized trial comparing letrozole and tamoxifen adjuvant therapy for postmenopausal early breast cancer: BIG 1–98. J Clin Oncol. 2007; 2:3846–3852.

- Hammond ME, Hayes DF, Dowsett M, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology/College Of American Pathologists guideline recommendations for immunohistochemical testing of estrogen and progesterone receptors in breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:2784–2795.

- Laenkholm AV, Grabau D, Talman ML, et al. An inter observer Ki67 reproducibility study applying two different assessment methods. On behalf of the Danish Scientific Committee of Pathology, Danish Breast Cancer Cooperative Group (DBCG). Acta Oncol. 2018; in press.

- Thorsen LB, Thomsen MS, Overgaard M, et al. Quality assurance of conventional non-CT-based internal mammary lymph node irradiation in a prospective Danish Breast Cancer Cooperative Group trial: the DBCG-IMN study. Acta Oncol. 2013;52:1526–1534.

- Thorsen LB, Thomsen MS, Berg M, et al. CT-planned internal mammary node radiotherapy in the DBCG-IMN study: benefit versus potentially harmful effects. Acta Oncol. 2014;53:1027–1034.

- Thorsen LB, Offersen BV, Danoe H, et al. DBCG-IMN: a population-based cohort study on the effect of internal mammary node irradiation in early node-positive breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:314–321.

- Christiansen P, Bjerre K, Ejlertsen B, et al. Mortality rates among early-stage hormone receptor–positive breast cancer patients: a population-based cohort study in Denmark. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103:1363–1372.

- Coombes RC, Hall E, Gibson LJ, et al. A randomized trial of exemestane after two to three years of tamoxifen therapy in postmenopausal women with primary breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1081–1092.

- BIG 1–98 Collaborative Group, Mouridsen H, Giobbie-Hurder A, et al. Letrozole therapy alone or in sequence with tamoxifen in women with breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:766–776.

- von Minckwitz G, Procter M, de Azambuja E, et al. Adjuvant pertuzumab and trastuzumab in early HER2-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:122–131.

- Francis P, Crown J, Di Leo A, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy with sequential or concurrent anthracycline and docetaxel: Breast International Group 02–98 randomized trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:121–133.

- Bria E, Nistico C, Cuppone F, et al. Benefit of taxanes as adjuvant chemotherapy for early breast cancer: pooled analysis of 15,500 patients. Cancer. 2006;106:2337–2344.

- Davis DA, Taylor-Vaisey A. Translating guidelines into practice. A systematic review of theoretic concepts, practical experience and research evidence in the adoption of clinical practice guidelines. CMAJ. 1997;157:408–416.

- Fischer F, Lange K, Klose K, et al. Barriers and strategies in guideline implementation-a scoping review. Healthcare (Basel). 2016;4:36.

- Banta D, Kristensen FB, Jonsson E. A history of health technology assessment at the European level. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2009;25(1):68–73.

- Nicholson BD, Mant D, Neal RD, et al. International variation in adherence to referral guidelines for suspected cancer: a secondary analysis of survey data. Br J Gen Pract. 2016;66:e106–e113.

- Austad B, Hetlevik I, Mjølstad BP, et al. Applying clinical guidelines in general practice: a qualitative study of potential complications. BMC Fam Pract. 2016;17:92.