Abstract

Background: This study examines information needs and satisfaction with provided information among childhood central nervous system (CNS) tumor survivors and their parents.

Material and methods: In a population-based sample of 697 adult survivors in Sweden, 518 survivors and 551 parents provided data. Information needs and satisfaction with information were studied using a multi-dimensional standardized questionnaire addressing information-related issues.

Results: Overall, 52% of the survivors and 48% of the parents reported no, or only minor, satisfaction with the extent of provided information, and 51% of the survivors expressed a need for more information than provided. The information received was found useful (to some extent/very much) by 53%, while 47% did not find it useful, or to a minor degree only. Obtaining written material was associated with greater satisfaction and usefulness of information. Dissatisfaction with information was associated with longer time since diagnosis, poorer current health status and female sex. The survivors experienced unmet information needs vis-à-vis late effects, illness education, rehabilitation and psychological services. Overall, parents were more dissatisfied than the survivors.

Conclusion: These findings have implications for improvements in information delivery. Information in childhood CNS tumor care and follow-up should specifically address issues where insufficiency was identified, and recognize persistent and with time changing needs at the successive stages of long-term survivorship.

Introduction

With a growing population of long-term survivors of childhood cancer, the importance of adequately provided information to patients and parents has received more attention as promotor of adjustment to illness. The goals of providing information include increasing patients’ understanding of the disease and preparing children and their families for the treatment and post-treatment follow-up. The benefits of information include increased adherence to treatment and abilities to cope with the illness, greater participation in treatment decisions, and improved sense of control [Citation1–3]. The concept of patients’ information needs has been defined as the basis from which to develop patient-centered services [Citation2]. ‘Information needs’ has been defined as the patient’s recognition that their knowledge is inadequate to satisfy a goal, within the context/situation that they find themselves at a specific point in time [Citation4]. The gap between the patients’ needs and the level of information disclosed can be defined as unmet information needs. The information needs may furthermore change over time and thus the importance of information continues throughout the entire illness trajectory. When it comes to childhood cancer, repeated information provision to patients is fundamental also for the reason that information at the time of illness may not be directly given to them, but to the parents [Citation2]. In Sweden, childhood cancer survivors are generally followed at the pediatric clinic until reaching 19 years of age, after which follow-up is less regular and often dependent on the survivor’s own initiative.

The problem of unmet information needs has been recognized in studies of diagnostically mixed childhood cancer patient groups. Findings of such studies show a certain consistency regarding the areas where information shortages are experienced as greatest, e.g., late effects and psychological services [Citation5–7]. Unmet information needs have been found associated with lower overall health, secondary comorbidities, psychological distress, worry about the future, and lower health-related quality of life [Citation2,Citation3,Citation7–10]. Individual psychological personality traits have also been found to be a potentially influential factor for patients' perception of information [Citation11].

Despite recognition of the crucial importance of patient information, the needs of long-term adult survivors and families of specific diagnostic sub-groups have been rarely attended to in large-scale studies. However, in a Swiss national questionnaire study of adult survivors of various childhood malignancies, results indicated a general need of both quantitatively and qualitatively enhanced information in specific areas, including personalized information and about late effects especially [Citation2,Citation7]. Among survivors of adult cancers, unmet information needs have been found associated with greater worries about the future and fears about disease recurrence [Citation8].

Among parents of children with cancer, a perceived lack of adequate information has been found associated with heightened psychological symptoms and lower quality of life [Citation3,Citation7], whereas the provision of effective and timely information potentially reduces anxiety due to a child’s cancer, and facilitate empowerment, and feeling of control and safety [Citation12].

Compared to other childhood cancers, children with CNS tumors constitute a high-risk group as regards a medical and psychosocial sequelae [Citation13–15]. Survivors and parents may therefore have specific care and information needs [Citation2,Citation16]. Also, the delivery of information may need to be adapted because of the relatively high prevalence of cognitive impairment [Citation17,Citation18]. Due to persistent late effects, many CNS tumor survivors do not live independently as adults, but with a prolonged dependence on families [Citation13]. The resulting extended parenthood contributes to why information needs should be considered even among parents of adult survivors.

The specific information needs associated with CNS tumor long-term survivorship and the extent to which these are perceived as met/unmet have to our knowledge not previously been investigated. The aim of this study was to study how of provided information and questions related to information needs is experienced in adult survivors of childhood CNS tumor and their parents. The following research questions were posed:

How do survivors’ experience provided information, and to what extent are survivors and parents satisfied with the extent and usefulness of the information provided?

Are there areas/issues where information needs are insufficiently met as experienced by survivors and parents, respectively?

Do information needs differ by demographic or illness-related factors such as sex, age, health status, type of CNS malignancy, level of education, and time since diagnosis?

To what extent do survivors and parents agree in their experienced information needs and satisfaction with received information?

We hypothesized that: (1) unmet information needs would be associated with current health status (more unmet information needs associated with poorer health status); (2) health status would be associated with satisfaction with information (poor health status associated with low satisfaction); and (3) health status would be associated with perceived usefulness with information (poor health status associated with perceived low usefulness).

Material and methods

Participants and procedures

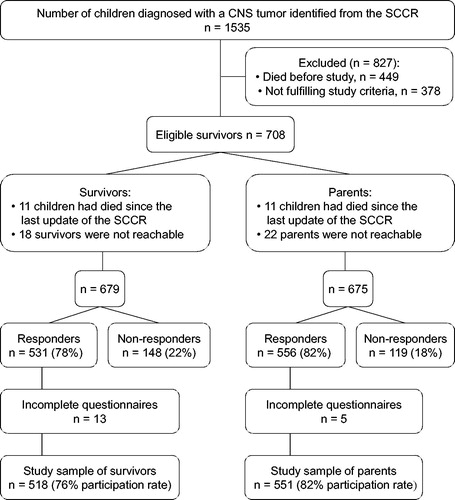

Participants were identified via the Swedish Childhood Cancer Registry (SCCR) with information about children diagnosed with a primary cancer diagnosis classified according to the third edition of the International Classification for Childhood Cancer [Citation19]. Survivors who met the following inclusion criteria were eligible for the study: a primary CNS tumor diagnosis between 1982 and 2001 before the 19th birthday, >5 years elapsed from diagnosis, and ≥18 years of age at the time of assessment. Of 1535 children diagnosed with a CNS tumor 1982–2001, 679 survivors were eligible for the study. Survivors and parents were asked to complete a booklet of self-report questionnaires. Questionnaires were returned from 531 survivors and 556 parents. In this study, thirteen returned, but incomplete survivor questionnaires and five parent questionnaires were excluded from analysis, resulting in a study sample of 518 survivors (76%) and 551 parents (82%) (). All the participants provided written informed consent. The study was approved by the Regional Research Ethics Committee (#2006/3-31/1).

Measurements

Information

Information needs, satisfaction with the quality (relevance/usefulness) of the information and the amount of information received were assessed by a study-specific questionnaire including areas similar to those of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) QLQ-INFO26 inventory [Citation1]. The questionnaire covered issues related to illness and treatment, medical tests, monitoring of late effects, psychological support, and rehabilitation services. Questions regarding the extent of information received were answered on a four-point Likert scale, ranging from ‘Not at all’ to ‘A great deal’.

In addition to the quantitative part, open-ended questions were posed regarding if the respondent had additional information needs that were not met by the information provided, or if they had preferred less information than provided. Respondents were asked to specify issues regarding which they had such additional unmet information needs.

Health status

We used the 15-item Health Utilities IndexTM Mark 2/3 (HUI2/3) for the assessment of survivors’ health status. The HUI2/3 has proven applicable across age groups and in various clinical and non-clinical populations [Citation20]. It allows establishing an overall health status score, which was used in the current study. The measure is based on a theoretical framework that describes individuals’ health on a scale, where dead = 0.00 and perfect health =1.00. Health status scores for states characterized by mild disability fall into the 0.89–0.99 range, states with moderate disability into the 0.70–0.88 range, while states with severe disability have scores <0.70 [Citation20].

Analyses

We provide descriptive statistics (mean, median, SD) for sociodemographic and medical characteristics of survivors and parents. Numbers and valid percentages are presented for outcomes relating to the extent of provided information pertaining to the specific fields defined and covered by the questionnaire, and for satisfaction with, and usefulness of information. An unmet information need was recorded among responders who reported having additional information needs, beyond what had been provided. Outcomes regarding open-ended questions are presented after classification into distinctive categories such as information about illness, treatment, late effects, psychological services and rehabilitation services. Satisfaction with information, perceived usefulness of the provided information, and having unmet information needs did not differ between parent responder constellations, i.e., whether the mother, the father, or parents together had responded to the questionnaire. Therefore, the data from all parent respondents were merged for analyses.

Differences in demographic and disease-related variables between responders and non-responders were first analyzed using t-test for independent groups and chi-square tests. Chi-square tests were conducted in analyses of associations between information satisfaction and demographic variables (age, survivors’ sex and education) and illness-related variables (survivors’ health status, diagnosis, age at diagnosis and time since diagnosis), respectively. Three binary logistic regression models were used to identify parameters that influence survivors’ and parents’ reports of provided information. Dependent variables were categorized as follows: information satisfaction (not at all/minor vs. some/a great deal), usefulness of information (not at all/minor vs. some/a great deal), and having unmet information needs (yes vs. no). Based on the results of bivariate tests, included independent variables were sex, time since diagnosis, level of education, if having received written information, and survivors’ age at assessment (the latter only for parent outcomes). Linear regression models were used to evaluate the association between information needs and overall health status in adjusted multivariable models.

Agreement between survivor- and parent reports of satisfaction and usefulness of information was evaluated using Kappa statistics, and by examining percentage agreement [Citation21].

Results

Study sample

Responding (n = 531) and non-responding survivors (n = 148) were similar in terms of age at assessment, time elapsed since diagnosis, sex, and diagnosis, but differed in age at diagnosis (t216=2.30, p = .02). Non-responders were younger at diagnosis (mean: 9.52 years; SD: 4.97) compared to responders (mean: 10.56 years, SD: 4.43). Responding (n = 556) and non-responding (n = 119) parents were similar regarding child’s sex, diagnosis, age at diagnosis, time elapsed since diagnosis, and age at follow-up. Returned questionnaires were completed by the mother alone (74%), the father alone (6%), or by parents together (20%). presents demographic characteristics of survivors in the final study group. Female survivors had lower educational outcomes (p = .045), significantly poorer health status (p = .002), and more often received social insurance/governmental subsidies (p = .028) than male survivors.

Table 1. Total group and comparisons between female and male survivors on sociodemographic and medical characteristics and survivors’ health status.

Survivor outcomes

Survivors reported that greatest amount of information (corresponding with the response alternative: ‘A great deal’) had been received about medical tests, including purpose of tests, medical procedures, and medical test results, followed by information about illness and treatment (including, diagnosis, spread of disease, and causes of disease). Survivors reported that least information had been received for other care services, including, e.g., psychological support and rehabilitation services (Supplementary Table 1). In total, 129 survivors (26%) reported that they had received written information about their illness and treatment. Eight survivors (2%) had received information on CD or videotape.

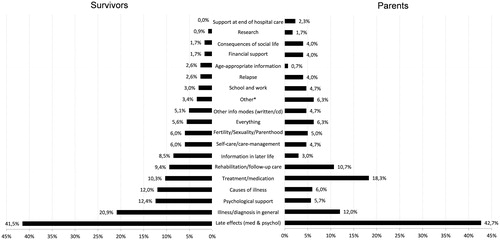

Survivors’ satisfaction with the extent and usefulness of the information provided are presented in . About half of the survivors (51%) were not at all, or only to some extent, satisfied with the extent of the information provided during treatment and follow-up. Information was found useful (to some extent/very much) by 53% of the survivors, while 33% found it useful to minor extent only, and 14% found it not at all useful (). Two hundred and sixty-three survivors (51%) reported unmet information needs (a need for more information than had been provided), whereas four survivors (1%) told that they had wanted less than what had been provided. The most frequently reported unmet information need concerned late effects (medical and psychological), the illness in general, and treatment-related issues ().

Figure 2. Areas of unmet information needs of survivors (n = 234) and parents (n = 300). *Includes (for survivors): time for talks with physician without parent(s) being present; one-to-one follow-up talks after the provision of initial information; ‘everything’ excluding medical aspects, and (for parents): the wish for better co-operation regarding information provision between care providers; time for talks with physician without the child being present; information about how to talk with the child; practical information about accommodation.

Table 2. Satisfaction with the extent of information and perceived usefulness of information among survivors and parents, by sex and health status.

Satisfaction with extent of information (χ2=34.71, p < .001), perceived usefulness of the provided information (χ2=29.81, p < .001), and prevalence of unmet information needs (χ2=10.59, p = .014) was associated with survivors’ health status (). After adjusting for confounders (sex, education, time since diagnosis and age) dissatisfaction with the extent of provided information (p < .001), dissatisfaction with the usefulness of information (p = .001), and reports of unmet information needs (p = .039) were still significantly associated with a poorer overall health status.

Bivariate analyses showed that female survivors were less satisfied with the extent of provided information than male survivors (χ2=19.36, p < .001), although there was no sex-related difference in perceived usefulness of the information (). Furthermore, a greater portion of females (62%, n = 150) than of males (45%, n = 113) reported unmet information needs (χ2=14.49, p < .001). Survivors with longer time elapsed since diagnosis reported lower satisfaction with the extent (χ2=30.61, p < .001) and usefulness (χ2=17.38, p = .043) of provided information, and more often reported unmet information needs (χ2=9.05, p = .029). In comparison with survivors who had not received written information, those who had received such reported greater satisfaction with the extent of information (χ2=45.89, p < .001), found provided information more useful (χ2=34.33, p < .001), and less often reported unmet information needs (χ2=27.89, p < .001). Education was unrelated to satisfaction with the extent of information. However, survivors with a low education level more often reported unmet information needs (χ2=7.32, p = .026), and less usefulness of information (χ2=8.46, p = .015). Age at diagnosis, survivors’ age at assessment, and type of CNS malignancy were unrelated to survivors’ appraisal of provided information and satisfaction with information.

Table 3. Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for survivors’ reports of being satisfied with the extent of information, finding the information provided useful, and having unmet information needs by sociodemographic and illness-related factors.

The results from the multivariable logistic regression analysis are presented in . After adjusting for the other variables in the model, greater satisfaction with the extent of information was significantly associated with having been provided written information, a shorter time since diagnosis and a better health status. Adjusted models further showed that survivors reporting the information provided as being useful more often were close (<10 years) in time to diagnosis, had been provided written information, had a better health status, and a high school graduate education level. Female survivors, survivors with a severe disability, and survivors reporting that they had not been provided written information more often reported unmet information needs.

Parent outcomes

Parents reported that greatest amount of information had been received regarding medical tests, followed by information about disease and treatment (Supplementary Table 1). On the other hand, parents told that least information had been provided regarding psychological support and about rehabilitation services.

Parents’ reports of satisfaction with the extent of information and perceived usefulness of the provided information at treatment and follow-up are presented in . Unmet information needs were reported by 338 parents (64%), while three parents (0.6%) had preferred less information than what was received. Late effects, access to psychological support, illness education, and follow-up were the areas where parents most often reported unmet information needs ().

In total, 114 parents (21%) told that they had received written information or a written summary of their child's illness and treatment, and five parents (1%) had received information on CD or videotape. Parents who had received written information reported greater satisfaction with the extent (χ2=33.81, p < .001), and greater usefulness of the provided information (χ2=23.69, p < .001) than did parents who had not received written information. Furthermore, parents of children with poorer health status were less satisfied with the extent of information provided (χ2=22.38, p = .008), reported less usefulness of the information received (χ2=17.08, p = .047), and more unmet information needs (χ2=12.99, p = .005). Parents of survivors with a longer time since diagnosis reported less satisfaction with the extent (χ2=19.00, p = .025), and usefulness of the provided information (χ2=23.53, p = .005). Time since diagnosis was however unrelated to parents' unmet information needs. Parents’ satisfaction with information, perceived usefulness of information, and prevalence of unmet information needs were unrelated to parents’ age, survivor's sex, and survivor's age at diagnosis. However, survivors’ age at assessment was related to parents' perceived usefulness of the provided information; parents of younger survivors found information more useful than did parents of older survivors (χ2=21.33, p = .011).

Results of the logistic regression analyses involving parents are presented in Supplementary Table 2. Multivariable models showed that the found associations remained after adjustment, except for association between time since diagnosis and perceived usefulness of the provided information.

Parent and survivor agreement

Poor to fair agreement between survivors’ and parents’ outcomes was found for perceived usefulness of the provided information (percentage agreement: 62%; Kappa value: 0.22), and for satisfaction with extent of information (percentage agreement: 64%; Kappa value: 0.29). Parents reported lower satisfaction with provided information, in terms of both extent and usefulness, than did survivors.

Discussion

This population-based study addressed information needs of survivors and parents after childhood CNS cancer treatment, and presents participants' experiences of provided information. Survivors and parents told that most information was received about medical interventions and treatment issues, while least information had been obtained about care services such as psychological support and rehabilitation. A large proportion of survivors and parents reported dissatisfaction with the extent and usefulness of the provided information, with every other survivor having unmet information needs. Among survivors, less positive appraisal of received information was associated with poorer current health status, longer time since diagnosis, female sex, and not having been provided written information. The results were in agreement with what was hypothesized.

Our study shows that survivors and parents had indeed received adequate information in a number of important areas including risks of relapse of malignancy, school/work, and financial support. Still, the indicated shortcomings of information delivery to CNS tumor survivors require attention and points out targets for improvement. In our study, about half of the survivors and parents were unsatisfied with the extent of provided information during treatment and follow-up. Furthermore, about half of the survivors perceived the provided information as hardly useful. These outcomes can be compared to those from a Dutch study of young adult thyroid cancer patients, in which the corresponding results were 47% (a little/not satisfied with the amount of information received) and 31% (a little/not helpful) [Citation22]. Also, our findings of the association between health status and information satisfaction confirm earlier findings where information factors have been found related to better health-related quality of life among adult cancer patients [Citation3].

According to participants, least information had been received about issues concerning potential effects of treatment on, e.g., patients’ life and sexuality as well as care services including self-care, rehabilitation and psychological support. These were also the areas where survivors and parents most frequently experienced unmet information needs. Remarkably, more than half of the survivors and parents told that they had not received any information at all regarding psychological support services. This finding is interesting in the light of prior study results where parents reported an experience of a lack of care-related psychological services [Citation23]. Alongside with other seemingly more important issues, children and parents also need qualified and specific information about available psychological services and about how to access such.

Overall, the results of our study can be compared to results from a Swiss national study addressing information-related outcomes among adult childhood cancer survivors (319 survivors; mean age 21.3 years, SD 4.1, response rate 45%) years old) [Citation2], and an Australian-New Zealandian study (322 survivors, mean age 26.7 years, SD = 7.9; 163 parents, response rate 59%) [Citation7]. However, those study groups comprised survivors of any type of malignancy, of which only 11% and 10%, respectively, were treated for a brain or CNS tumor. Although the findings from adjacent studies indicate similar needs of information improvements, differences in study groups and used outcome measures prevent direct comparison of outcomes. Still, areas associated with most frequently reported unmet information needs have been partly similar, including late effects, above all [Citation2,Citation7]. In our study, 51% of the survivors indicated unmet information needs in response to the specific question in our questionnaire. In the Swiss and the Australian-New Zealandian studies an unmet need was reported by 87% and 77% of survivors, respectively [Citation2,Citation7]. The difference in these numbers between our study and the two others is not easily interpretable. It could be explained by differences in prevailing information routines in study sites, the differences study groups (mixed vs. brain/CNS cancers), or the difference in method (assessment questionnaires). Also, unequal response rates may play a role, as lower response rates in the comparison studies (59% and 45%) may be associated with selection bias with bearing on outcomes.

Our finding that both survivors and parents reported need for improved information about late consequences of illness supports outcomes of prior investigations of survivors of mixed childhood cancer diagnoses [Citation2,Citation7,Citation17,Citation24]. This finding is of importance for structuring timely and extended information routines for CNS tumor patients who are at considerable risk of both immediate and late occurring sequelae. In particular, the heightened risk for neurocognitive impairment among these patients plays a significant role in the provision of adapted and accessible information [Citation18]. Insufficient information seems to put survivors and families at risk of remaining unaware of the individual risk of sequelae, and unprepared for managing sequelae that may occur.

Results were in agreement with our hypotheses that a poorer health status of the survivor was associated with unmet information needs and with lower satisfaction with the information received, among both survivors and parents. The current results are largely in line with what is known regarding cancer survivors of different cancer types [Citation2,Citation3,Citation7,Citation8] Dissatisfaction among those who already suffer from compromised health or functional disability shows the need for enhanced and individualized information. Written or internet-based sources that provide general information about illness consequences are insufficient for that, and should be complemented with updated personalized information provision when necessary. The possible benefits of multi-modal information provision in form of oral, written, audio-visual information has been put forth in earlier studies [Citation16,Citation17]. Still, the value of providing survivors with a written treatment summary only has been debated [Citation25], and its relation to satisfaction does not seem obvious [Citation7,Citation16]. The results of this study draw attention to the potential benefits by showing that survivors who had received written information were more satisfied with the information provided. That just one out of four survivors and one out of five parents reported receiving written illness- and treatment-related information remains a clear target for improvement.

Female survivors were less satisfied with the extent of provided information and reported more of unmet information needs than did male survivors. As indicated by the current results, a possible contributing explanation to this might be that the female survivors in our study group present poorer health status compared to male survivors [Citation26]. Still, even after controlling for the effect of current health status, female survivors reported more of unmet information needs than male survivors. This finding warrants further investigation in future studies.

Some study limitations should be considered. Firstly, retrospective recall of provided information could be subject to recall bias and/or selectivity, a possible bias as regards reports of the early diagnosis-treatment period. Secondly, the cross-sectional design of the study allows conclusions about associations between information appraisals and factors such as survivor’ health status, while causal relationships cannot be determined. Forthcoming research should involve longitudinal studies to address causal interrelationships, and expand focus to the relationships between information needs and potential illness and treatment-related variables and psychological social factors, respectively. Moreover, when interpreting our findings, we need to consider the complexity and challenges of communication under potentially stressful circumstances. It is possible that adequate and more complete information was in fact provided than what the patient/parent could assimilate at the time, and afterwards be able to fully recall. Distress and strain may have blocked understanding and assimilating of early provided information, and obscured memorizing and later recalling – a phenomenon that can interfere with the intentions of information [Citation27]. Early stage information delivery of today may be improved, and the importance of repeated checkups of information needs are perhaps better known than they were at the time of treatment of survivors in our study. However, this study shows that adult survivors of childhood CNS tumors and their families have information needs that are insufficiently met by current standards of long-term follow-up care. Information needs to better pay attention to individual demands, and acknowledge that needs can alter considerably during long-term survival and adult life.

Conclusions

A considerable proportion of adult childhood CNS tumor survivors and their parents have unmet information needs and report dissatisfaction with the provided information. Results show the importance of adopting both patient and family perspectives in information provision. Information insufficiency was greatest for those with a longer time since diagnosis, poorer health status, and female survivors. Long-term surveillance of these patients should include targeted individualized information, reassessment of information needs regarding late-occurring sequelae, and consider psychological support needs.

Emma_Hoven_et_al._Supplementary_TABLES.docx

Download MS Word (47.8 KB)Disclosure statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Arraras JI, Kuljanic-Vlasic K, Bjordal K, et al. EORTC QLQ-INFO26: a questionnaire to assess information given to cancer patients a preliminary analysis in eight countries. Psycho-Oncol. 2007;16:249–254.

- Gianinazzi ME, Essig S, Rueegg CS, et al. Information provision and information needs in adult survivors of childhood cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2014;61:312–318.

- Husson O, Mols F, van de Poll-Franse LV. The relation between information provision and health-related quality of life, anxiety and depression among cancer survivors: a systematic review. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:761–772.

- Ormandy P. Defining information need in health – assimilating complex theories derived from information science. Health Expect. 2011;14:92–104.

- Pöder U, von Essen L. Perceptions of support among Swedish parents of children on cancer treatment: a prospective, longitudinal study. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2009;18:350–357.

- Zebrack BJ, Block R, Hayes-Lattin B, et al. Psychosocial service use and unmet need among recently diagnosed adolescent and young adult cancer patients. Cancer. 2013;119:201–214.

- Vetsch J, Fardell JE, Wakefield CE, et al. “Forewarned and forearmed”: long-term childhood cancer survivors' and parents' information needs and implications for survivorship models of care. Patient Educ Couns. 2017;100:355–363.

- O'Malley DM, Hudson SV, Ohman-Strickland PA, et al. Follow-up care education and information: identifying cancer survivors in need of more guidance. J Cancer Educ. 2016;31:63–69.

- Oerlemans S, Husson O, Mols F, et al. Perceived information provision and satisfaction among lymphoma and multiple myeloma survivors-results from a Dutch population-based study. Ann Hematol. 2012;91:1587–1595.

- Husson O, Oerlemans S, Mols F, et al. Satisfaction with information provision is associated with baseline but not with follow-up quality of life among lymphoma patients: results from the PROFILES registry. Acta Oncol. 2014;53:917–926.

- Husson O, Denollet J, Oerlemans S, et al. Satisfaction with information provision in cancer patients and the moderating effect of Type D personality. Psychooncology. 2013;22:2124–2132.

- Kastel A, Enskar K, Bjork O. Parents' views on information in childhood cancer care. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2011;15:290–295.

- Hjern A, Lindblad F, Boman KK. Disability in adult survivors of childhood cancer: a Swedish national cohort study. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:5262–5266.

- Oeffinger KC, Mertens AC, Sklar CA, et al. Chronic health conditions in adult survivors of childhood cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1572–1582.

- Boman KK, Lindblad F, Hjern A. Long-term outcomes of childhood cancer survivors in Sweden: a population-based study of education, employment, and income. Cancer. 2010;116:1385–1391.

- Vetsch J, Rueegg CS, Gianinazzi ME, et al. Information needs in parents of long-term childhood cancer survivors. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62:859–866.

- Trask CL, Welch JJG, Manley P, et al. Parental needs for information related to neurocognitive late effects from pediatric cancer and its treatment. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2009;52:273–279.

- Ellenberg L, Liu Q, Gioia G, et al. Neurocognitive status in long-term survivors of childhood CNS malignancies: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. Neuropsychology. 2009;23:705–717.

- Steliarova-Foucher E, Stiller C, Lacour B, et al. International classification of childhood cancer, third edition. Cancer. 2005;103:1457–1467.

- Furlong WJ, Feeny DH, Torrance GW, et al. The health utilities index (HUI (R)) system for assessing health-related quality of life in clinical studies. Ann Med. 2001;33:375–384.

- Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33:159–174.

- Husson O, Mols F, Oranje WA, et al. Unmet information needs and impact of cancer in (long-term) thyroid cancer survivors: results of the PROFILES registry. Psychooncology. 2014;23:946–952.

- Ljungman L, Boger M, Ander M, et al. Impressions that last: particularly negative and positive experiences reported by parents five years after the end of a child's successful cancer treatment or death. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0157076.

- Knijnenburg SL, Kremer LC, van den Bos C, et al. Health information needs of childhood cancer survivors and their family. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2010;54:123–127.

- Kadan-Lottick NS, Robison LL, Gurney JG, et al. Childhood cancer survivors' knowledge about their past diagnosis and treatment - childhood cancer survivor study. JAMA. 2002;287:1832–1839.

- Boman KK, Hoven E, Anclair M, et al. Health and persistent functional late effects in adult survivors of childhood CNS tumours: a population-based cohort study. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:2552–2561.

- Jedlicka-Kohler I, Gotz M, Eichler I. Parents' recollection of the initial communication of the diagnosis of cystic fibrosis. Pediatrics. 1996;97:204–209.