Abstract

Introduction: This study aimed to explore the feasibility of an individualized comprehensive lifestyle intervention in cancer patients undergoing curative or palliative chemotherapy.

Material and methods: At one cancer center, serving a population of 180,000, 100 consecutive of 161 eligible newly diagnosed cancer patients starting curative or palliative chemotherapy entered a 12-month comprehensive, individualized lifestyle intervention. Participants received a grouped startup course and monthly counseling, based on self-reported and electronically evaluated lifestyle behaviors. Patients with completed baseline and end of study measurements are included in the final analyses. Patients who did not complete end of study measurements are defined as dropouts.

Results: More completers (n = 61) vs. dropouts (n = 39) were married or living together (87 vs. 69%, p = .031), and significantly higher baseline physical activity levels (960 vs. 489 min.wk−1, p = .010), more healthy dietary choices (14 vs 11 points, p = .038) and fewer smokers (8 vs. 23%, p = .036) were observed among completers vs. dropouts. Logistic regression revealed younger (odds ratios (OR): 0.95, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.91, 0.99) and more patients diagnosed with breast cancer vs. more severe cancer types (OR: 0.16, 95% CI: 0.04, 0.56) among completers vs. dropouts. Improvements were observed in completers healthy (37%, p < 0.001) and unhealthy dietary habits (23%, p = .002), and distress (94%, p < .001). No significant reductions were observed in physical activity levels. Patients treated with palliative intent did not reduce their physical activity levels while healthy dietary habits (38%, p = 0.021) and distress (104%, p = 0.012) was improved.

Discussion: Favorable and possibly clinical relevant lifestyle changes were observed in cancer patients undergoing curative or palliative chemotherapy after a 12-month comprehensive and individualized lifestyle intervention. Palliative patients were able to participate and to improve their lifestyle behaviors.

Introduction

Physical activity (PA), a healthy diet, stress management and smoking cessation is recommended during and after oncological treatment to manage cancer-related symptoms, prevent early and late co-morbidities, increase the rate of chemotherapy cycles and possibly extend overall and disease-specific survival [Citation1–5]. However, few cancer patients currently meet these lifestyle recommendations [Citation6–8] and undergoing chemotherapy is negatively associated with adherence to a healthy lifestyle [Citation9]. Furthermore, previous lifestyle interventions have typically focused on only one lifestyle behavior [Citation10] and are commonly based on a ‘one size fits all’-approach [Citation2,Citation11]. The current literature is thus based on selected samples of a minority of the youngest, healthiest, fittest and most motivated cancer patients with limited potential to further improve their lifestyles. Importantly, these studies were commonly performed ‘after’ completion of chemotherapy, usually in patients in an adjuvant setting [Citation12–14]. Lifestyle interventions in patients undergoing chemotherapy with palliative intent are almost absent [Citation15–17], although this may be a window to adapt strategies for increased control and empowerment in a setting characterized by lack of control, vulnerability and uncertainty for patients with incurable disease [Citation18]. Further, this may be a critical phase to reduce therapy-induced side effects [Citation3,Citation19]. A reason for lack of research in this area may be interference with clinical logistics or ‘gatekeeping’ issues, where healthcare professionals ‘protect’ patients with advanced disease from potential unnecessary strain [Citation20]. In conclusion, based on the selection bias of the previous lifestyle interventions conducted, the feasibility of the current guidelines in cancer patients undergoing active oncological treatment can be questioned. Clinicians thus have limited evidence to base their guidance upon in patients undergoing chemotherapy; especially for patients in a palliative setting [Citation17,Citation19].

The primary objective of the present study was thus to explore the feasibility of a population-based and individualized comprehensive lifestyle intervention with follow-up of four and 12 months after inclusion focusing on diet, PA, stress management and smoking cessation in 100 consecutive newly diagnosed cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy with curative or palliative intent. Feasibility was predefined as a > 20% improvement in > two lifestyle behaviors in >70% of the eligible cancer patients at the Center for Cancer Treatment. Secondary objectives were to identify subgroup feasibility differences in completion rate and feasibility among patients in a curative vs. palliative treatment intent.

Material and methods

I CAN Individualized comprehensive lifestyle interventions in cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy (I CAN) is a 12-month single-arm feasibility study in cancer patients undergoing curative or palliative chemotherapy. I CAN aims to increase adherence to healthy lifestyle behaviors, based on participants preferences and barriers, including a healthy diet [Citation21], PA [Citation2], stress management [Citation22] and smoking cessation [Citation23]. The intervention is described in detail previously [Citation24].

Sample

Between January 2013 and May 2014, all newly diagnosed cancer patients receiving chemotherapy with either curative or palliative intent at the Center for Cancer Treatment in Kristiansand/Norway, serving a population of 180,000 inhabitants, were considered for inclusion to the present I CAN study according to the following criteria: (1) second cycle of chemotherapy; (2) age ≥18 years; (3) life expectancy ≥6 months; (4) Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG) ≤ 2 and (5) able to speak and read Norwegian. Exclusion criteria were suspected anorexia cachexia syndrome and severe mental disorder (evaluated by the patients primary physician). The detailed inclusion process is described previously [Citation24].

Patients with completed baseline and end of study measurements are included in the final analyses. Patients who for some reason did not complete end of study measurements are defined as dropouts.

The study was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration and approved by the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics, South-East (2012/1717). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Intervention

Initially participants and relatives were invited to a voluntary grouped startup course to learn about lifestyle recommendations and practical suggestions on adapting a healthier lifestyle during chemotherapy. Next, participants received an information binder with evidence-based lifestyle recommendations, recipes for healthy foods and beverages, PA and stress management suggestions and also a list with common side effects with ideas on how to manage these. Participants were also offered monthly individual lifestyle counseling over 12-months during the participants appointment at the Center for Cancer Treatment. The individualized lifestyle counseling was facilitated through a dedicated software application developed to monitor and evaluate self-report outcomes and provide immediate feedback on the participants lifestyle behaviors, after specific adaptation for the I CAN study (GoTreatIT Cancer) [Citation25].

Measures

Assessment of medical and demographic variables is described in detail previously [Citation24]. Tumor type was categorized into breast; colorectal ; prostate; and other cancer types (gastric, pancreas, gallbladder, urinary bladder, hepatic and origo incerta), respectively. The latter group (other cancer types) was pooled in one group, since they comprised cancers with expected similarly short median survival and a frequently high burden of cancer-related symptoms. Complex self-report of the participants lifestyle habits and quality of life (QOL, (European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30 (EORTC QLQ-C30)) [Citation26] consisting of 106 questions was conducted at baseline, four months and end of study, while a shorter self-report consisting of 30 questions was conducted monthly. As part of a validation study [Citation27], participants wore a SenseWear Armband after two and four months to obtain objective measures of PA levels.

Participants lifestyle behaviors were entered directly into electronic questionnaires in GoTreatIT Cancer [Citation25] by one of the lifestyle counselors. The lifestyle counselors were two oncologic nurses and a PhD student with a Master degree in sports science. GoTreatIT categorized participants responses into healthy and unhealthy lifestyle behaviors; healthy included PA and healthy diet components, while unhealthy included sedentary time, unhealthy diet, cancer-specific distress and cigarette smoking (). To easily monitor participants month-by-month lifestyle changes and their adherence to the lifestyle recommendations, healthy and unhealthy lifestyle behaviors were scored ranging from one to five; one corresponded to low adherence to the recommendations and five corresponded to high adherence ().

Table 1. Lifestyle scoring system within the different lifestyle behaviors ranging from 1 (low adherence) to 5 (high adherence).

Physical activity and sedentary time

Self-reported PA and sedentary time was assessed using the short form of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ-sf) according to Guidelines for Data Processing and Analysis developed by the IPAQ-group [Citation28]. PA was classified as either vigorous PA (VPA), moderate PA (MPA) or walking. Total time spent walking, MPA or VPA activities was calculated and included as beneficial habits and the score was based on cutoffs from the IPAQ-sf [Citation28]. The number of hours and minutes sitting was calculated which represented the participants sedentary time or unhealthy lifestyle behavior within the PA domain ().

All walking was defined as MPA, as proposed by Craig et al. [Citation29]. PA was defined as the sum of time in Moderate-to-Vigorous intensity PA (MVPA).

Diet

According to the Norwegian dietary advice to promote public health and prevent disease [Citation21], diet was classified into seven different food groups: (1) fruits, berries and vegetables; (2) grains (whole grains vs. white bread); (3) meat (fish and white meat vs. red and processed meat); (4) fat (saturated vs. unsaturated fat); (5) sugar; (6) salt and (7) alcohol. Diet quality was then assessed by a seven-day recall of 13 different food items or food groups (e.g., ‘How many servings of vegetables did you usually eat per day the last week?’). Dietary score was categorized into a healthy and unhealthy diet score based on the recommendations from the Norwegian dietary advice [Citation21] ().

Cancer-specific distress

Subjective stress related to being diagnosed with cancer was assessed by the Impact of Event Scale (IES) according to Horowitz et al. [Citation30]. A total subjective stress score of >26 defined moderate to severe impact [Citation30] () and participants scoring >26 were offered a stress management course by the hospital’s patient education center.

Cigarette smoking

Cigarette smoking was assessed by asking ‘Did you smoke any cigarettes the past month?’. If yes: ‘How many cigarettes did you smoke on average per day/week?’ ().

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics are presented as mean and standard deviation (SD) or as median and interquartile range (IQR). Stratified analyses were conducted to test for statistical differences in baseline characteristics between treatment intent groups (curative vs. palliative). Logistic regression analyses were performed to calculate odds ratios (OR) for completing the end of study measurements, with medical and socio-demographic characteristics and baseline lifestyle behaviors included in the model. Results are presented as OR with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Due to multi-collinearity, gender, diagnosis type, tumor stage and treatment intent were not included in the same model.

The relative change from baseline to four month and end of study in each lifestyle behavior was calculated for each participant with completed end of study registrations. Mixed models analyses were applied, with different lifestyle behaviors at end of study as dependent and visit number as independent variables. An interaction term of treatment intent groups and visit number was included in separate models, to explore changes in palliative participants lifestyle behaviors. Changes are presented as regression coefficients (B) and 95% CI.

Level of significance was set to 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS statistical software version 22 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

Recruitment

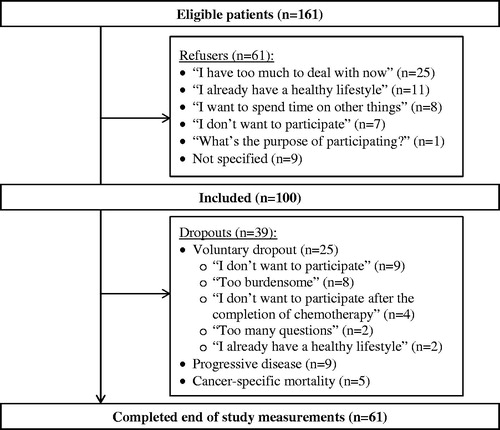

Over a 16-month period, 197 newly diagnosed cancer patients started their treatment with either curative or palliative chemotherapy, of which 161 were eligible for inclusion. The 36 excluded patients are described previously [Citation24]. In total 100 patients (62%) agreed to participate and completed baseline lifestyle assessments (). Baseline socio-demographic, medical characteristics and lifestyle variables are presented in and .

Table 2. Baseline socio-demographic and medical characteristics of I CAN participants, categorized by treatment intent (curative vs. palliative).Table Footnotea

Table 3 Absolute baseline lifestyle values from all participants also stratified into completers (n = 61) and dropouts (n = 39).Table Footnotea

Completers and dropouts

In total 61 participants (21 palliative) completed end of study measurements (), corresponding to 38% of 161 eligible patients. Median adherence to counseled sessions in all participants was six visits (IQR: 6). Completers and dropouts attended eight (IQR: 6) vs. two (IQR: 4) visits, respectively (p < .001). In total, 17 participants completed 100% of scheduled visits. The 61 who completed the end of study measurements, were more often married or living together vs. dropouts (87 vs. 69%, respectively, p = .031). Higher baseline levels of MVPA (960 vs. 489 min.wk−1, respectively, p = .010), more healthy dietary choices (14 vs. 11 points, p = .038) and fewer smokers (8 vs. 23%, p = .036) were observed among completers vs. dropouts, respectively (). In logistic regression analyzes, age and diagnosis were associated with completion (Nagelkerke 0.24). Completers were significantly younger than dropouts (OR: 0.95, CI: 0.91, 0.99) and more often diagnosed with breast cancer vs. ‘other’ cancer types (0.16 (0.04, 0.56)). Gender, socio-demographic variables, smoking status, body mass index(BMI), ECOG, treatment intent, QOL or distress levels at baseline was not associated with dropout.

Four and 12-month lifestyle changes

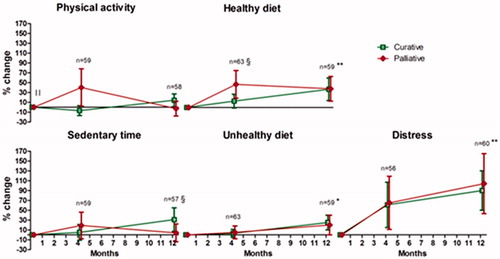

Relative lifestyle changes (%) from baseline are presented in for the 61 participants who completed the end of study measurements. Mixed models analyses revealed significant improvements in completers healthy (coefficient B: 0.04, 95% CI: 0.02, 0.06) and unhealthy diet (0.02 (0.01, 0.04)) during the 12-month intervention. Completers also significantly improved their cancer-specific distress (0.84 (0.05, 0.12)) from baseline to end of study. Mean improvements observed for healthy and unhealthy diet were 37% (p < .001) and 23% (p = .002), respectively, while a 94% change in cancer-specific distress was observed in all completers (p < .001). Palliative patients significantly improved their healthy dietary habits (38%, p = .021) and distress (104%, p = .012) during the study. After four months, palliative patients improved their healthy dietary habits significantly more vs. curative patients (0.10 (0.01, 0.20)). MVPA levels were significantly lower at baseline in palliative (597, 95% CI: 302, 892 min.wk−1) vs. curative patients (904, 95% CI: 677, 1131 min.wk−1;−0.52 (−0.86, −0.19)); however, no significant changes from baseline to end of study were observed in either groups. Still, a trend towards larger improvements in palliative vs. curative patients MVPA levels were observed after four months (0.15 (−0.01, 0.30)). Mixed models analyses revealed that sedentary time changed differently in curative vs. palliative patients from baseline to end of study: sedentary time was reduced in curative patients, but increased in palliative patients (−0.06 (−0.09, −0.02)). For cigarette smoking, no significant changes were observed (0.01 (−0.01, 0.02)) (data not shown).

Figure 2. Twelve-month lifestyle changes. An improved percentage change is favorable for all lifestyle behaviors, based on the scores from . ǁStatistical significant difference between treatment intent groups at baseline (p < .05); §Statistical significant interaction between treatment intent group and visit number (p < .05); *Statistical significant improvement over time in all (p < .05) and ** (p < .001).

Discussion

I CAN is, to our knowledge, the first study to examine the feasibility of a comprehensive and individualized lifestyle intervention in a newly diagnosed population-based cohort of cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy with both curative and palliative intent.

In total, 38% of eligible patients completed the study. They improved their dietary habits by ∼30% and reduced cancer specific distress by 94% during the 12-month intervention, despite the fact that completers self-reported a lifestyle in line with the lifestyle recommendations already at baseline. Importantly, PA levels did not decrease during a 12-month intervention in cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. We defined ‘feasibility’ for this study as increasing at least two lifestyle behaviors by at least 20%. This definition was reached, however, by improving lifestyle behaviors in – again – a selected sample of a healthier and younger subset of eligible patients.

The study aimed at retaining >70% of eligible patients through a low-threshold and individualized study design. Our observed completion rate of 38% of eligible patients is lower than aimed for. Comparing the pre-defined feasibility cutoff in the present study to other studies, aiming at completing >70% of eligible patients in a 12-month lifestyle intervention while undergoing active oncologic treatment might have been too ambitious. A recently published feasibility study in adults with lung cancer defined feasibility as a ≥ 20% enrollment and a completion rate of 70% for five nurse-patient contact sessions [Citation31]. Yet, this is contrary to a survey from our outpatient clinic, where 26 of 27 consecutive queried patients would have appreciated a lifestyle intervention during oncological treatment if it existed (unpublished results). Compared to dropouts, completers of the present study were typically nonsmokers, younger with higher levels of baseline MVPA and a trend towards a healthier diet. Additionally, participation in the present study was deterred by increasing age and cigarette smoking [Citation24]; we did not succeed including as many elderly and unhealthy patients as aimed for. One reason for the high dropout, may be dissatisfaction with the data acquisition burden which resulted in less focus on the individualized counseling, as expressed through qualitative in-depth interviews in palliative and curative patients [Citation32,Citation33]. This was despite the fact that the number of questions was reduced to 30 during monthly counseled sessions. Nonetheless, selective dropout of the oldest and least healthy participants is in accordance with previous studies reporting a ‘healthy volunteer bias’ in lifestyle interventions [Citation24,Citation34]. On the other hand, a dropout rate of 39% in the present study is lower compared to previous lifestyle interventions in cancer patients undergoing palliative chemotherapy [Citation20].

Previous studies have reported completion rates from less than 10 to 50% of eligible patients [Citation20,Citation35–37]. Importantly, previous studies used as benchmark for comparison rate [Citation38] have practiced more selective patient inclusion, often in a curative setting ‘after’ the completion of their oncological treatment in ‘single’ behavioral interventions of ‘shorter’ duration, typically six to 14 weeks [Citation12,Citation13,Citation38].

Our findings that cancer patients undergoing active oncological treatment were not only able to sustain, but also improve aspects of their lifestyle, with significant improvements observed for dietary habits and cancer-specific distress, are presumably of important clinical relevance. Importantly, I CAN is, to our knowledge, the first lifestyle intervention study demonstrating the feasibility of a comprehensive and individualized lifestyle intervention in cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy, particularly in a palliative setting. For cancer-specific stress, the observed reduction in the present study may be attributed to either a ‘ceiling’ or ‘floor’ effect, described as a decrease in emotional distress from time of diagnosis to follow-up [Citation39], or simply due to available support in the standard care [Citation40], as described previously.

Since previous lifestyle intervention investigators have reported that receiving chemotherapy is associated with lower compliance to healthy lifestyle behaviors [Citation6,Citation9,Citation13], our observations of improved dietary habits and maintained PA level during a 12-month low-threshold lifestyle intervention in cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy are promising, but cannot be ascribed to participation in the I CAN study alone [Citation1–3,Citation5].

Study limitations

The study is inevitably limited by the lack of control group, making it impossible to establish any causal effect of the observed lifestyle changes. Next, the present study is limited by the exclusion of 36 patients, creating an under representation of patients treated with palliative intent due to a gatekeeping process in the present study. However, and importantly; we observed no significant differences between participants and those who refused to participate with regard to treatment intent. We believe these findings support the conclusion that there is no need for gatekeeping of patients in a palliative treatment setting from future lifestyle interventions.

Changes in smoking habits were not depicted due to a low number of smokers included and subsequently increased risk of type 2 errors. Next, when using self-report and assessing lifestyle behaviors with seven-day retrospection, recall bias is likely to occur; particularly in a population experiencing disease and treatment-related side effects such as ‘chemobrain’ and memory loss [Citation41]. Objective measures, i.e., activity monitors and IT-tools for assessing lifestyle behaviors at home in ‘real life settings’, may be possible solutions to the self-report issues in a population with difficulties in self-reporting [Citation27]. This would also release time for extra counseling of patients in the clinic, since I CAN participants reported dissatisfaction with the burden of 30 questions monthly [Citation33]. Future studies are also encouraged to include structured use and measures of behavior change theories (i.e., motivation, self-regulation and resources) to provide the patients with more individualized interventions and to identify theoretical explanations for behavior change in cancer patients undergoing active treatment [Citation42]. Lack of these measures are a limitation of the present study.

Clinical implications

The implications of lifestyle changes in patients treated with palliative intent should be further elaborated [Citation17]. Since no differences in the inclusion or completion of curative or palliative patients were observed, we find that palliative patients are just as willing and able to participate in a sustained lifestyle as patients treated with curative intent. Next, cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy with palliative intent were able to maintain their lifestyle behaviors during the 12-month I CAN study. Healthy dietary habits and cancer-related distress were even improved in this patient group. Specifically, after participating for four months, palliative patients significantly improved their healthy dietary habits more than curative patients; a trend also observed for PA level. In fact, after four months, palliative patients reported a 40% increased PA level vs. a 7% ‘decrease’ in curative patients. Thus, a ‘reversed U-shape’ was observed in palliative patients healthy dietary habits and PA levels, with a peak after four months, before returning towards, but importantly not below baseline levels at end of study after twelve months. These findings are encouraging, especially since participation in the I CAN study was a beneficial experience in patients treated with palliative intent, as explored in qualitative in-depth interviews [Citation32]. Findings from the qualitative interviews show that participation provided palliative patients with boosted confidence, hope for the future and facilitated for them to take on a more active role during treatment [Citation32]. Consequently, ‘gatekeeping’ of patients in a palliative setting appears to be both unfortunate and unnecessary. Our findings may be of clinical relevance with regard to harvesting potential benefits such as improved QOL, well-being, physical functioning and fatigue [Citation15,Citation16]. Although not an objective of the present study, increased tolerability to clinically relevant oncological treatments may have been facilitated by altered lifestyle in some patients [Citation3]. Combined with documented feasibility of lifestyle interventions here and previously reported sense of increased control [Citation32], lifestyle intervention studies with survival endpoints in patients with advanced cancer, but a reasonable life expectancy, should be encouraged.

For the first time, the feasibility of a comprehensive and individualized lifestyle intervention has been compared directly between curative and palliative patients, providing us with a unique insight into the potential positive role of lifestyle interventions in patients undergoing palliative chemotherapy. This is a major strength of the present study.

In conclusion, favorable and possibly clinical relevant lifestyle changes were observed in cancer patients undergoing curative or palliative chemotherapy after a 12-month comprehensive and individualized lifestyle intervention. Importantly, palliative patients are willing and able to participate and even maintain their lifestyles during a 12-month lifestyle intervention, while undergoing chemotherapy. Our findings encourage future lifestyle interventions in cancer patients with advanced disease.

Acknowledgments

The authors would first humbly like to thank the participants of the present study for providing their valuable time and effort. We also thank the outpatient clinic at the Center for Cancer Treatment at the Sorlandet Hospital Trust for their collaboration, with a special thanks to the oncologic nurses Brit Hausken Haddeland and Marit Kristin Bjelland Lund who greatly contributed in the study by collecting data and supervising I CAN participants. We would also like to thank Are Hugo Pripp for sharing his expertise in mixed models analyses.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Sung B, Prasad S, Yadav V, et al. Cancer and diet: how are they related? Free Radic Res. 2011;45:864–879.

- Rock C, Doyle C, Demark-Wahnefried W, et al. Nutrition and physical activity guidelines for cancer survivors. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:243–274.

- van Waart H, Stuiver M, van Harten W, et al. Effect of low-intensity physical activity and moderate- to high-intensity physical exercise during adjuvant chemotherapy on physical fitness, fatigue, and chemotherapy completion rates: results of the PACES randomized clinical trial. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:1918–1927.

- Hara M, Kovacs J, Whalen E, et al. A stress response pathway regulates DNA damage through β2-adrenoreceptors and β-arrestin-1. Nature. 2011;477:349–353.

- Osborn R, Demoncada A, Feuerstein M. Psychosocial interventions for depression, anxiety, and quality of life in cancer survivors: meta-analyses. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2006;36:13–34.

- Blanchard CM, Courneya KS, Stein K. Cancer survivors' adherence to lifestyle behavior recommendations and associations with health-related quality of life: results from the American cancer society's SCS-II. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2198–2204.

- Tannenbaum S, McClure L, Asfar T, et al. Are cancer survivors physically active? A comparison by U.S. States. J Phys Ach Health. 2015;13:159–167.

- Foucaut A, Berthouze S, Touillaud M, et al. Deterioration of physical activity level and metabolic risk factors after early-stage breast cancer diagnosis. Cancer Nurs. 2014;38:E1–E9.

- Kelly K, Bhattacharya R, Dickinson S, et al. Health behaviors among breast cancer patients and survivors. Cancer Nurs. 2015; 38:E27–E34.

- Pekmezi D, Demark-Wahnefried W. Updated evidence in support of diet and exercise interventions in cancer survivors. Acta Oncol. 2011;50:167–178.

- Buffart L, Galvâo D, Brug J, et al. Evidence-based physical activity guidelines for cancer survivors: current guidelines, knowledge gaps and future research directions. Cancer Treat Rev. 2014; 40:327–340.

- van Waart H, van Harten W, Buffart L, et al. Why do patients choose (not) to participate in an exercise trial during adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer? Psychooncology. 2015;25:964–970.

- Maunsell E, Drolet M, Brisson J, et al. Dietary change after breast cancer: extent, predictors, and relation with psychological distress. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:1017–1025.

- Bourke L, Thompson G, Gibson D, et al. Pragmatic lifestyle intervention in patients recovering from colon cancer: a randomized controlled pilot study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;92:749–755.

- Lowe S, Watanabe S, Courneya K. Physical activity as a support care intervention in palliative cancer patients: a systematic review. J Support Oncol. 2009;7:27–34.

- Bazzan A, Newberg A, Cho W, et al. Diet and nutrition in cancer survivorship and palliative care. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:1.

- Sheean P, Kabir C, Rao R, et al. Exploring diet, physical activity, and quality of life in females with metastatic breast cancer: a pilot study to support future intervention. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2015;115:1690–1698.

- Thomsen T, Rydahl‐Hansen S, Wagner L. A review of potential factors relevant to coping in patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Nurs. 2010;19:3410–3426.

- Lowe S. Physical activity and palliative cancer care. Recent Results Cancer Res. 2011;186:349–365.

- Oldervoll L, Loge J, Paltiel H, et al. Are palliative cancer patients willing and able to participate in a physical exercise program? Palliat Support Care. 2005;3:281–287.

- Helsedirektoratet (The Norwegian Directorate of Health). Kostråd for å fremme folkehelsen og forebygge kroniske sykdommer (Dietary Advice to Promote Public Health and Prevent Chronic Diseases). Oslo (Norway): Helsedirektoratet (The Norwegian Directorate of Health); 2011. Norwegian.

- Nordin K, Rissanen R, Ahlgren J, et al. Design of the study: how can health care help female breast cancer patients reduce their stress symptoms? A randomized intervention study with stepped care. BMC Cancer. 2012;12:167.

- Helsedirektoratet (The Norwegian Directorate of Health). Helsedirektoratets plan for et systematisk og kunnskapsbasert tilbud om røyke- og snusavvenning (The Norwegian Directorate of Healths' Plan for a Systematic and Evidence Based Offer of Smoking and Tobacco Cessation). Oslo Helsedirektoratet (The Norwegian Directorate of Health); 2012. Norwegian.

- Vassbakk-Brovold K, Berntsen S, Fegran L, et al. Individualized comprehensive lifestyle intervention in patients undergoing chemotherapy with curative or palliative intent: who participates? PLoS One. 2015;10:e0131355.

- DiaGraphIT AS - Clinical monitoring software. GoTreatIT® Cancer research and development project 2012. [Internet]; [cited 2015 Apr 14]. Available from: http://diagraphit.com/index.php? expand=82&show=82&topmenu_2=19.

- Ringdal G, Ringdal K. Testing the EORTC Quality of life questionnaire on cancer patients with heterogeneous diagnoses. Qual Life Res. 1993;2:129–140.

- Vassbakk-Brovold K, Kersten C, Fegran L, et al. Cancer patients participating in a lifestyle intervention during chemotherapy greatly over-report their physical activity level: a validation study. BMC Sports Sci Med Rehabil. 2016;8:10.

- IPAQ-group. Guidelines for Data Processing and Analysis of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) Short Form 2004. [Internet]; [cited 2015 Apr 14]. Available from: http://www.institutferran.org/documentos/Scoring_short_ipaq_april04.pdf.

- Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjöström M, et al. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35:1381–1395.

- Horowitz M, Wilner N, Alvarez W. Impact of event scale: a measure of subjective stress. Psychosom Med. 1979;41:209–218.

- Blok A, Blonquist T, Nayak M, et al. Feasibility and acceptability of “healthy directions” a lifestyle intervention for adults with lung cancer. Psychooncology. 2017 [cited 2017 May 31]. DOI:10.1002/pon.4443

- Mikkelsen H, Brovold K, Berntsen S, et al. Palliative cancer patients experiences of participating in a lifestyle intervention study while receiving chemotherapy. Cancer Nurs. 2015;38:E52–E58.

- Vassbakk-Brovold K, Antonsen AJ, Berntsen S, et al. Experiences of patients with breast cancer of participating in a lifestyle intervention study while receiving adjuvant chemotherapy. Cancer Nurs. 2017 [cited 2017 Feb 17]. DOI: 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000476

- de Souto Barreto P, Ferrandez A, Saliba-Serre B. Are older adults who volunteer to participate in an exercise study fitter and healthier than nonvolunteers? The participation bias of the study population. J Phys Act Health. 2013;10:359–367.

- Ornish D, Lin J, Chan JM, et al. Effect of comprehensive lifestyle changes on telomerase activity and telomere length in men with biopsy-proven low-risk prostate cancer: 5-year follow-up of a descriptive pilot study. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:1112–1120.

- Grimmett C, Simon A, Lawson V, et al. Diet and physical activity intervention in colorectal cancer survivors: a feasibility study. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2015;19:1–6.

- Andersen B, Farrar W, Golden-Kreutz D, et al. Psychological, behavioral, and immune changes after a psychological intervention: a clinical trial. J Clin Oncol.2004;22:3570–3580.

- Husebø A, Dyrstad S, Søreide J, et al. Predicting exercise adherence in cancer patients and survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis of motivational and behavioural factors. J Clin Nurs. 2013;22:4–21.

- Brandberg Y, Michelson H, Nilsson B, et al. Quality of life in women with breast cancer during the first year after random assignment to adjuvant treatment with marrow-supported high-dose chemotherapy with cyclophosphamide, thiotepa, and carboplatin or tailored therapy with Fluorouracil, epirubicin, and cyclophosphamide: Scandinavian Breast Group Study 9401. J Clin Oncol. `2003;21:3659–3664.

- Johansson B, Brandberg Y, Hellbom M, et al. Health-related quality of life and distress in cancer patients: results from a large randomised study. Br J Cancer. 2008;99:1975–1983.

- Ganz P. Doctor, will the treatment you are recommending cause chemobrain?” ? J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:229–231.

- Kwasnicka D, Dombrowski S, White M, et al. Theoretical explanations for maintenance of behaviour change: a systematic review of behaviour theories. Health Psychol Review. 2016;10:277–296.