Introduction

Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm (BPDCN), currently considered to arise from precursors of the type 2 or plasmacytoid dendritic cells (DC), is a very rare and aggressive CD4 + CD56 + neoplasm that frequently involves the skin and bone marrow [Citation1,Citation2]. Most patients with BPDCN frequently present with cutaneous lesions, followed by dissemination to the peripheral blood, bone marrow and lymph nodes. Involvement of the tonsils, paranasal cavities, lungs, orbital cavity, conjunctival, central nervous system (CNS) and paravertebral area have also been reported [Citation3–7]. In patients presenting with altered mental status, headache or other neurological symptoms, leptomeningeal involvement should be considered. Although involvement of the CNS is not uncommon in BPDCN, to our knowledge, optic nerve involvement of BPDCN has not been reported before. Herein, we report the first case of sudden onset complete monocular vision loss due to optic nerve involvement of BPDCN, which is an unexpected association between a rare disease and a devastating symptom.

Case report

A 61-year-old man with past history of type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension and hepatitis B was admitted to our ward due to sudden onset of left eye visual acuity decrement noted three days ago when he woke up in the morning with mild left eye pain. He went to the ophthalmology outpatient department initially, and was then referred to our neurology department for further evaluation.

Tracing back to his history, seven months ago, he noticed persistent nasal congestion, progressive general weakness, increasing skin nodules and bruise-like patches around the anterior chest wall. Fiberscope showed tumors around the whole nasopharynx with ecchymosis, and his oropharynx showed buggy tonsils, with buggy tumors over the right side. The physical examination revealed bilateral neck lymphadenopathy and bilateral inguinal lymphadenopathy. The abdominal computed tomography (CT) showed lymphoma with multiple variable size lymphadenopathies along the hepatoduodenal ligament, left para-aortic region, bilateral common iliac vessels, left obturator space, left external iliac vessels and bilateral inguinal regions. The biopsy of the left inguinal lymph node revealed BPDCN, with diffuse monotonous infiltrate of blast cells with medium cell size and scant agranular cytoplasm positive for CD56, CD4, CD123, TCL-1 and LCA, but negative for CK, HMB-45, TIA-1, CD3, CD20, CD5,CD30, ALK, TdT, CD21 and PAX-5. The cytogenetic study showed 6q deletion. BPDCN with bone marrow and skin involvement, stage IV, was thus diagnosed five months ago, and he underwent regular follow-up in our hematology outpatient department for chemotherapy, post fifth course of CHOP therapy (cyclophosphamide, hydroxydaunorubicin, vincristine and prednisone).

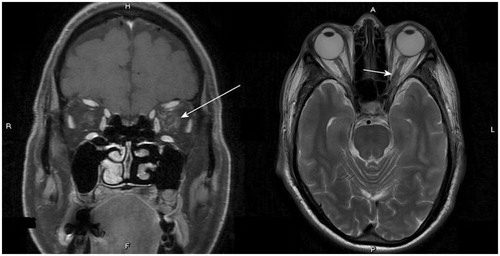

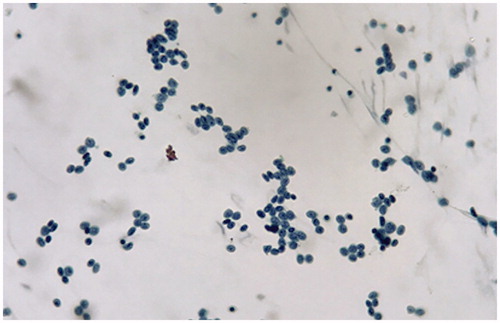

In addition to his left eye vision loss, there were no preceding fever, trauma, headache, cognitive impairment, right eye involvement and pain with extraocular movement. The neurological examination revealed impaired visual acuity of the left eye, while no other neurological symptoms/signs including meningeal signs were detected. In the ophthalmologic examination, the best corrected visual acuity of the right eye was 1.0 with only light perception in the left eye. Intraocular pressures were 17mmHg in both eyes. Pupillary diameter was 3.5mm bilaterally, but with marked sluggish reactivity and relative afferent pupillary defect (RAPD) in the left eye. Anterior segment exam showed normal result. Dilated fundoscopic exam showed clear disc border and color bilaterally, without edema in the optic nerve, intraretinal hemorrhages, white spots and retinitis. Optical coherence topography (OCT) showed normal findings. Auto-perimetry showed loss of left eye visual field entirely. The brain and orbital magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with enhancement showed swollen retrobulbar intra-orbital segment of the left optic nerve, which appeared hyperintense on T2-weighted images and not significantly enhanced on the post-enhanced T1-weighted images. Heterogeneous enhancement of the orbital fat was noted bilaterally and is more severe over the left side (), which favored infiltration of the left optic nerve by neoplasm. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) study showed a total WBC count of 750/cumm with abnormal cell, protein 146mg/dL and sugar 46mg/dL (blood sugar 127mg/dL), with normal intracranial pressure (130mmH2O). The cytology of CSF showed increased leukocytes of immature blast type and lymphocytes, suspicious for malignant cells ().

Figure 1. Left panel: On the post-enhanced T1W images of the brain MRI, heterogeneous enhancement of the orbital fat was noted bilaterally, which is more severe over the left side (arrow). Infiltration of the optic nerve by neoplasm is likely. Right panel: On the T2-weighted images of the brain MRI, there was swollen retrobulbar intra-orbital segment of the left optic nerve (arrow).

Figure 2. CSF study showed increased leukocytes of immature blast type with high N/C ratios and thick nuclear membrane in Pap stain.

Since the left eye retrobulbar optic neuritis was caused by cancer cell infiltration, we administered methylprednisolone 500mg IVD every 12 hours for three days. However, his visual acuity remained the same after steroid treatment. Due to his original scheduled chemotherapy, the patient was transferred to the hematology ward and promptly received intrathecal chemotherapy of low dose 30mg cytarabine. CSF cell count became 0 after the fourth dose of intrathecal cytarabine and CSF cytology also showed significant improvement. However, there was no improvement of his left visual acuity. One month later, the patient received bone marrow transplant (BMT) and pre-transplant whole-body irradiation was performed.

Discussion

Most patients with BPDCN present with cutaneous lesions with or without bone marrow involvement and leukemic dissemination. The skin lesions of BPDCN can be brown to violaceous bruise-like lesions, plaques or tumors and may be solitary or widespread. Besides, cytopenia, lymphadenopathy and/or splenomegaly are presented in a significant majority of patients with BPDCN. Central nervous system (CNS) involvement has also been reported. In a retrospective series of 90 patients with BPDCN, CNS involvement was demonstrated in 11% of the patients [Citation8]. Detection of leptomeningeal disease typically occurs only after a patient presents with neurological symptoms. Patients with neurological signs or symptoms should undergo imaging studies for evaluation of meningeal disease or CNS involvement. If there is no contraindication, lumbar puncture should be performed in all patients, given the high incidence of occult CSF involvement [Citation8]. CSF should be sent for both cytology and flow cytometry. This is significant because leptomeningeal BPDCN may associate with a poor prognosis and decreased rate of complete response compared to absence of leptomeningeal disease. Based on another recent research, a lot of BPDCN patients may suffer from occult CNS involvement without any neurological symptoms/signs. The high incidence of CNS involvement suggests that the CNS may be a persistent blast-cell sanctuary in BPDCN patients with leukemic presentation, caused by the limited ability of cytostatic drugs to cross the blood-brain-barrier into the CSF and cerebral tissues [Citation9]. There is a paucity of data to guide the treatment of patients with BPDCN, and the optimal treatment is unknown. Some suggests that patients receiving ALL-like therapy were more likely to achieve a complete remission (CR) and significantly longer overall survival compared with patients receiving AML-like therapy [Citation8,Citation9]. While CNS prophylaxis is routinely incorporated into ALL treatment protocols, whether CNS prophylaxis should be routinely incorporated into BPDCN treatment protocols is still unknown. However, based on limited evidence, BPDCN patients with occult CNS involvement at diagnosis may benefit from CNS-directed therapy if administered early at diagnosis. These CNS-directed therapies may have potential to reverse the poor outcome of BPDCN patients [Citation8,Citation9].

Involvement of orbital cavity [Citation5] and conjunctiva [Citation6] has been reported in patients with BPDCN, but optic nerve involvement has never been reported before. This is the first report of a patient with BPDCN who presented with complete monocular vision loss due to involvement of the optic nerve. This is an unexpected association between a rare disease and a devastating symptom. This case report contributes to the limited literature that we currently have on BPDCN and highlights the need for better understanding with the goal of early diagnosis in patients who have known risk factors for CNS involvement, which can lead to proper therapy such as timely intrathecal chemotherapy, and furthermore, for taking preventive steps to avoid devastating complications.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- Marafioti T, Paterson JC, Ballabio E, et al. Novel markers of normal and neoplastic human plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Blood. 2008;111:3778–3792.

- Arber DA, Orazi A, Hasserjian R, et al. The 2016 revision to the world health organization classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia. Blood. 2016;127:2391–2405.

- Pagano L, Valentini CG, Pulsoni A, et al. Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm with leukemic presentation: an Italian multicenter study. Haematologica. 2013;98:239–246.

- Feuillard J, Jacob MC, Valensi F, et al. Clinical and biologic features of CD4(+)CD56(+) malignancies. Blood. 2002;99:1556–1563.

- Inoue D, Maruyama K, Aoki K, et al. Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm expressing the CD13 myeloid antigen. Acta Haematol. 2011;126:122–128.

- Matsuo T, Ichimura K, Tanaka T, et al. Bilateral conjunctival lesions in blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm. J Clin Exp Hematop. 2011;51:49–55.

- Vigemyr G. [An young boy with an atypic rash]. Tidsskr nor Laegeforen. 2014;134:946–948.

- Julia F, Petrella T, Beylot-Barry M, et al. Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm: clinical features in 90 patients. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:579–586.

- Martin-Martin L, Almeida J, Pomares H, et al. Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm frequently shows occult central nervous system involvement at diagnosis and benefits from intrathecal therapy. Oncotarget. 2016;7:10174–10181.