Abstract

Background: While the link between mental illness and cancer survival is well established, few studies have focused on colorectal cancer. We examined outcomes of colorectal cancer among persons with a history of severe mental illness (SMI).

Material and methods: We identified patients with their first colorectal cancer diagnosis in 1990–2013 (n = 41,708) from the Finnish Cancer Registry, hospital admissions due to SMI preceding cancer diagnosis (n = 2382) from the Hospital Discharge Register and deaths from the Causes of Death statistics. Cox regression models were used to study the impact on SMI to mortality differences.

Results: We found excess colorectal cancer mortality among persons with a history of psychosis and with substance use disorder. When controlling for age, comorbidity, stage at presentation and treatment, excess mortality risk among men with a history of psychosis was 1.72 (1.46–2.04) and women 1.37 (1.20–1.57). Among men with substance use disorder, the excess risk was 1.22 (1.09–1.37).

Conclusion: Understanding factors contributing to excess mortality among persons with a history of psychosis or substance use requires more detailed clinical studies and studies of care processes among these vulnerable patient groups. Collaboration between patients, mental health care and oncological teams is needed to improve outcomes of care.

Introduction

Mental disorders are associated with remarkably increased mortality compared to the general population [Citation1]. Somatic illnesses due to poorer health behaviors (smoking, unhealthy diet and physical inactivity), side effects of psychotropic drugs, poorer access to and quality of treatment in somatic illnesses and increased suicide mortality have been suggested to cause the reduced life expectancy associated with long-term mental illnesses. Further, the cognitive and affective problems associated with mental illness may impair these patients ability to navigate the health care system [Citation2–6]. Results from earlier research suggest that cancer risk among persons with severe mental illness (SMI) may not be elevated [Citation7,Citation8], but results of some studies suggest that they present with more severe stage [Citation7,Citation9,Citation10]. Earlier results further indicate that persons with SMI have worse cancer survival not explained by stage at presentation [Citation7,Citation11–14] suggesting that unequal provision of cancer care may play a role in mortality differences. Earlier studies have also reported reduced likelihood of surgery, less radiotherapy and fewer chemotherapy sessions among persons with SMI [Citation7].

While the link between mental illness and cancer survival is well established, few studies have examined colorectal cancer more specifically. Colorectal cancer is one of the most incident cancers in modern societies. In Finland, it is one of the top three cancers among both men and women. Earlier studies from other countries suggest both elevated [Citation11] and reduced colorectal cancer incidence [Citation7,Citation12,Citation15] among persons with SMI but consistently higher case-fatality [Citation7,Citation11]. Many of the studies examining the effect of SMI to case-fatality of colorectal cancer up to date have examined case-fatality as part of a larger study examining several cancer sites. A few studies have focused on colorectal cancer. Baillargeon et al. [Citation9] examined colorectal cancer in the US among elderly population and reported that people with preexisting SMI and especially psychosis were less likely to be diagnosed at local cancer stage and more likely to be diagnosed with unknown stage, to have not received surgery, radiotherapy or chemotherapy and to have higher cancer specific mortality risk compared to those without a history of SMI. Cunningham et al. [Citation10] analyzed colorectal cancer mortality among patients with functional psychosis and reported that stage at presentation accounted for 39% of the survival difference between them and persons with no SMI and adjusting further for comorbidity and deprivation did not abolish the mortality difference.

The aim of the current study was to examine whether outcomes of colorectal cancer vary between persons with a history of severe mental illness and those without. We further analyzed whether survival differences could be explained by age, year of cancer diagnosis, cancer stage at presentation, comorbidities, or differences in cancer treatment. In addition, we examined whether changes in the differences in survival could be found during the study period. We examined all cancer patients in Finland with their first colorectal cancer episode in 1990–2013 and focused on colorectal cancer specific mortality.

Material and methods

The study population

The people with their first colorectal cancer diagnosis in 1990–2013 were identified from the national population-based Finnish Cancer Registry (FCR). The FCR includes practically all cancer patients in Finland since 1953 and the data were examined back until 1969 to ensure including only the first cancer diagnosis for each individual. In the FCR, cases are coded using the ICD-O-3 that can be converted to the corresponding ICD-10-codes. In this study, ICD-10 codes C18-19 and C20-21 were used to define colorectal cancer. Cancers morphologically defined as lymphoma were excluded from the analyses (n = 241). We defined severe mental illness (SMI) as mental disorder requiring hospital treatment at some point of its course, as the illness in these cases had obviously caused serious functional impairment at some point of the course of the illness. Data on hospital admissions due to SMI among the patient cohort one year before cancer diagnosis or earlier were obtained from the Hospital Discharge Register and individually linked to the cancer data. Hospitalizations due to SMI were also backdated to year 1969. We used three main categories of mental illness, namely substance use disorder (SUD) (ICD-10 code F10-19 and corresponding ICD-9 and ICD-8 codes), schizophrenia spectrum psychotic disorders, hereafter called psychosis (F20, F22-29) and mood disorders (F30-33, F38-39) as a main diagnosis in hospitalization one year before the cancer diagnosis or earlier in order to ensure the incidence of SMI was not linked to cancer. Persons classified in any of the SMI groups remained in the SMI population from the first hospitalization until the end of the follow-up period or death due to the long natural course of SMI. If an individual had several hospital admissions and had been given a main diagnosis belonging to more than one SMI category, we hierarchically allocated the individual to the psychosis subpopulation if diagnosed with psychosis at least once. Patients with both SUD and mood disorder related diagnoses were allocated to the SUD group. Cancers defined morphologically as lymphoma (n = 241) were excluded from the colorectal cancer cases. Persons among whom colorectal cancer was first diagnosed at autopsy (n = 2828) were excluded from the analyses as they lacked information of cancer care. Information concerning cancer specific and all-cause mortality was obtained from the Causes of Death statistics maintained by Statistics Finland. Cancer specific deaths were defined using the underlying cause of death and used as the main outcome of the study, but all models were also performed using all-cause mortality. Cancer patients were followed up until the end of 2014, death or moving abroad, whichever earliest.

Covariates

Morphology of cancers was obtained from the FCR and classified into adenocarcinoma (ICD-O-3 code M8140), mucinous adenocarcinoma (M8480) and others, with some 80% of cancers morphologically classified as adenocarcinomas. Cancer topography was classified as (1) neoplasm of cecum and appendix (ICD-O-3 codes C18.0, C18.1), (2) of sigmoid colon (C18.7), (3) other parts of colon (C18.2–18.6, C18.8–18.9, C19.9) and 4) neoplasm of rectum, anus and anal canal (C20-21).

Cancer stage at presentation was also obtained from the FCR and categorized as (1) localized, (2) metastasized (regional or distant) and (3) unknown. Cancer treatment was classified as (1) surgical treatment only, (2) surgical treatment + radiotherapy, (3) surgical treatment + chemotherapy, (4) surgical treatment + radiotherapy + chemotherapy, (5) other and (6) no treatment or unknown.

Comorbidity was defined from the Hospital Discharge Register data for each individual. We calculated a modified Charlson’s comorbidity index [Citation16] from hospitalizations for several diseases (congestive heart failure, peripheral vascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, dementia, chronic pulmonary disease, rheumatic disease, peptic ulcer disease, liver disease, diabetes with or without chronic complications, hemiplegia or paraplegia and renal disease) within one year preceding cancer diagnosis.

Men and women were analyzed separately. Age at presentation was categorized in five-year age bands and year of cancer diagnosis was used as a continuous variable. Ethical approval for the study was received from the Research Ethics Committee of the National Institute for Health and Welfare.

Statistical methods

We calculated crude proportions of persons with a history of SMI among incident colorectal cancer patients and Kaplan-Meier estimates to examine crude survival differences between patient groups (data not shown). Cox regression models were conducted in three phases to examine the impact of covariates on patient group differences in cancer-specific mortality in the whole study period. In the first phase, we estimated hazard ratios for each patient group adjusting for age, year of first cancer episode, cancer type (topography and morphology) and Charlson’s comorbidity index. In the next phase, we further adjusted for cancer stage at presentation. In the third phase, cancer treatment was also added into the model. Generalized R2 was calculated to allow for assessment of goodness in the prediction of mortality for each set of covariates in three phases of Cox regression models [Citation17]. We estimated cumulative hazards adjusted for all covariates in the third phase model and stratified by patient group to illustrate the differences in survival in patient groups. In order to estimate hazard ratios for equivalent potential follow-up in the beginning and towards the end of the study period, we examined Cox regression models with five-year follow-up in three periods (1990–1994, 1997–2001 and 2004–2008). We added an interaction term between time period and patient group to study whether any changes in group differences could be found in time period of cancer presentation. SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) was used in statistical analyses of the study.

Results

There were altogether 22,125 new colorectal cancer cases among men and 22, 651 among women in 1990–2013 in Finland. While most colorectal cancer cases were diagnosed based on a histological excision of the primary tumor (ca 90%), altogether 7% of these cancers among men and 6% among women in the original data were found at autopsy (altogether 2828 cases). Colorectal cancer was first diagnosed at autopsy more often among persons with a history of SUD or psychosis compared to persons without a history of SMI. These cases were excluded from further analysis. presents some basic background characteristics of the study population. Of the cohort, 6% of men and 5% of women had a history of SMI. Among men, the largest group of SMI was SUD and among women, psychosis and mood disorders ().

Table 1. Basic background characteristics of population with first colorectal cancer in 1990–2013 in Finland, by sex and history of severe mental illness (SMI) categoryTable Footnotea.

Among more than half of persons with their first colorectal cancer, the treatment was surgical only and approximately a fifth of the patients had undergone surgery plus chemotherapy or radiotherapy. The number of people with no or unknown treatment was slightly higher among men and women with a history of psychosis compared to the other patient groups. Persons with a history of psychosis also had fewer combination therapies. As each of the patient groups with a history of SMI proved in preliminary analysis to be too small for multivariate analysis, we did not examine treatment differences further.

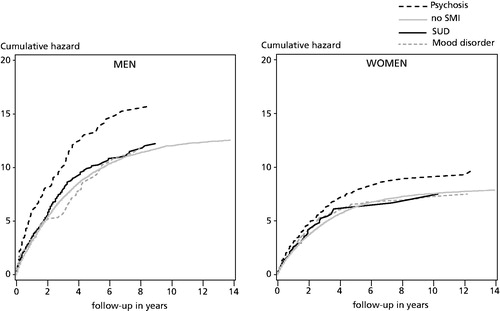

The cumulative hazards in suggest that colorectal cancer mortality was higher among persons with a history of psychosis, whereas there were only small differences between other SMI groups and those without a history of SMI. The group differences remained fairly stable during the follow-up. The cumulative hazards were on a higher level in all patient groups among men compared to women.

Figure 1. Cumulative hazard of colorectal cancer mortality among Finnish men and women with their first cancer episode in 1990–2013 (lines cut at 14 years).

presents the risk of colorectal cancer mortality among the four patient groups and changes in the mortality risk in three phases when taking into account age, cancer topography and morphology, comorbidities and year of cancer diagnosis (Model I), cancer stage at presentation (Model II) and cancer treatment (Model III). When taking into account only age, cancer type (morphology and topography), comorbidities and year of cancer diagnosis, men with a history of psychosis or substance use problems had higher mortality risk compared to those without a history of SMI. An increased mortality risk was also found among women with a history of psychosis. However, these factors accounted only for a small proportion of variance between the groups as indicated by the generalized R2 values. Although accounting for an important part of the variation between population groups, controlling for stage at presentation did not alter the results substantively. This was also true when examining the effect of cancer treatment. After all the adjustments, men with a history of psychosis had a 1.7-fold cause-specific mortality risk compared to those without a history of SMI. The corresponding figure was 1.4 among women with a history of psychosis. When examining all-cause mortality, the results were, in general, similar to those for cancer specific mortality, but the generalized R2’s were somewhat higher and adding cancer stage or treatment in the model did not change them substantially (results not shown).

Table 2. Effect of history with severe mental illness (SMI) on colorectal cancer mortality among Finnish men and women in 1990–2013a.

When examining five-year colorectal cancer mortality trends among persons with their first cancer episode in three time periods (1990–1994, 1997–2001 and 2004–2008), we found no significant interactions between time period and patient group in men (p = .346) or women (p = .079) and were not able to report changes in time in the differences between persons with previous history of any of the studied SMI and those without ().

Table 3. Hazard ratios (HR) and their 95% confidence intervals (CI) for five-year colorectal cancer mortality among incident cancer patients with a history of severe mental illness (SMI) in three time periods in 1990–2013.

Discussion

Overview of the main findings

In this register based study, we examined the effect of history of severe mental illness to colorectal cancer mortality among a population of patients with their first colorectal cancer episode in 1990–2013. In line with earlier studies, we found higher case-fatality among persons with a history of psychosis and men with a history of substance use disorder [Citation7,Citation11]. In line with Baillargeon et al. [Citation9], we found that people with a history of psychosis had higher cancer-specific mortality risk compared to those without a history of SMI. In line with Cunningham et al. [Citation10], we found that stage at presentation accounted for some of the differences between the patient groups with and without history of SMI, but did not affect the mortality risk significantly. We found no statistically significant changes in five-year mortality differences during the study period. This suggests that the mortality gap between people with psychotic and substance use disorder compared to those without SMI has remained stable, i.e., survival from colorectal cancer has improved over time also in people with SMI.

An interesting finding was that colorectal cancer was first diagnosed at autopsy more often among persons with a history of SUD or psychosis compared to persons without a history of SMI. Gastrointestinal symptoms are common in patients with psychotic disorders [Citation18] and constipation related to antipsychotic treatment can sometimes lead to paralytic ileus, bowel occlusion and even death [Citation19]. It seems plausible that the symptoms of colorectal cancer may not be recognized in time due to similar side effects caused by antipsychotic drugs. Alcohol [Citation20] and drugs of abuse [Citation21,Citation22] are associated with gastrointestinal symptoms and diseases, but sometimes also to reduced visceral pain, which may mask an underlying cancer in patients with SUD. It should, however, be noted that only in two thirds of the cancers found in autopsy the underlying cause of death was colorectal cancer. In addition, probability of autopsy is not likely to be similar in all patient groups.

After adjusting for cancer topography and morphology, stage at presentation, cancer treatment and comorbidities, a significant proportion of excess cancer mortality still remained unexplained among people with psychotic and substance use disorders. A limitation of the study is that our data on treatment were relatively crude. We did not have information on surgical treatment modalities, which may affect the outcome of surgery [Citation23] or the type or dose of chemotherapy and radiotherapy received by the patients. Furthermore, we did not have any information on adherence to treatment, nor on other possible problems in cancer treatment. Neither did we have information concerning lifestyle, e.g., smoking and substance use other than that resulting into hospital inpatient care. Further studies should also examine the care processes in order to understand why especially men with a history of psychosis seem to have large excess mortality independent of stage at presentation.

The Finnish health care system is mainly publicly funded with universal access to services for all residents and supports equal treatment according to need to all patients [Citation24]. Primary health care is organized in municipal health centers, occupational health services and private services. While the diagnostic process in cancers usually begins in primary care, where first diagnostic tests are also usually performed, a preliminary diagnosis of cancer leads to referral to specialist care [Citation25]. Oncologic services are in Finland mainly provided in specialist care organized in 20 hospital districts managed and funded by municipalities supplying specialist services for the residents and specialist services should be delivered to patients according to clinical need irrespective of other health problems that the patients face.

Methodological considerations

The strength of our study was the use of nationwide, representative register data covering the total population of Finnish residents with their first colorectal cancer episode in 1990–2013. The data were collected from the nationwide Finnish Cancer Registry and Hospital Discharge Register, both of which are based on clinical diagnoses. Notification of cancer to the FCR is mandatory in Finland. The FCR has been reported to have a high coverage of incident colorectal cancer cases and the accuracy of the records has been found to be good [Citation26–29]. The overall accuracy and coverage of the Hospital Discharge Register has also been reported to be good [Citation30]. The Finnish Causes of Death statistics are considered to be valid and reliable by international standards [Citation31] and the evaluation of cancer-specific deaths at the FCR further improves the accuracy of the analyzes. Furthermore, confirmation of the diagnosis by autopsy in Finland is high compared to many other countries (in 2014, 23% for all deaths and 53% of those under 65 years of age) [Citation32]. Earlier studies of colorectal cancer survival have been based on samples [Citation9], had relatively short follow-up periods [Citation10], and examined specific age-groups [Citation9,Citation10].

A weakness in our study is that our data concerning SMI covered only people who had been hospitalized due to these illnesses and less severe mental illness was not accounted for. While most patients with psychotic disorder are hospitalized at some point of their illness, hospital-treated substance use and mood disorders capture only the most severe forms of these disorders [Citation33]. While a deinstitutionalization of psychiatric care took place in Finland as in other industrialized countries in the 1990s and early 2000s, most patients with psychotic disorders are hospitalized at some point of their illness and as a broad category schizophrenia spectrum psychotic disorders are reliable although schizophrenia tends to be under-diagnosed into ‘milder’ forms of psychotic disorders in clinical practice. In contrast, substance use and mood disorders requiring hospital treatment represent the most severe forms of these disorders [Citation34,Citation35]. Furthermore, as the SMI episode could have been any time between 1970 and year preceding first cancer diagnosis, our study is likely to yield a conservative estimate of the differences. However, since these patients are already in touch with health services due to their mental health problems, the availability and quality of health care is easier to estimate.

Conclusion

Patients with psychotic and substance use disorders have higher cancer-specific mortality than other patients with colorectal cancer explained only partly by differences in stage at presentation and cancer treatment. Understanding all contributing factors requires more detailed clinical studies on the causes of excess mortality. Collaboration between patients, mental health care professionals and oncological teams is needed in order to improve cancer care in this vulnerable patient group.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest that would have biased the work.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Gissler M, Laursen TM, Osby U, et al. Patterns in mortality among people with severe mental disorders across birth cohorts: a register-based study of Denmark and Finland in 1982–2006. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:834.

- Allen J, Balfour R, Bell R, et al. Social determinants of mental health. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2014;26:392–407.

- Crawford MJ, Jayakumar S, Lemmey SJ, et al. Assessment and treatment of physical health problems among people with schizophrenia: national cross-sectional study. Br J Psychiatry. 2014;205:473–477.

- Gladigau EL, Fazio TN, Hannam JP, et al. Increased cardiovascular risk in patients with severe mental illness. Intern Med J. 2014;44:65–69.

- Laursen TM, Munk-Olsen T, Nordentoft M, et al. Increased mortality among patients admitted with major psychiatric disorders: a register-based study comparing mortality in unipolar depressive disorder, bipolar affective disorder, schizoaffective disorder, and schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68:899–907.

- McNamee L, Mead G, MacGillivray S, et al. Schizophrenia, poor physical health and physical activity: evidence-based interventions are required to reduce major health inequalities. Br J Psychiatry. 2013;203:239–241.

- Kisely S, Crowe E, Lawrence D. Cancer-related mortality in people with mental illness. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70:209–217.

- Lawrence DM, Holman CD, Jablensky AV, et al. Death rate from ischaemic heart disease in Western Australian psychiatric patients 1980-1998. Br J Psychiatry. 2003;182:31–36.

- Baillargeon J, Kuo YF, Lin YL, et al. Effect of mental disorders on diagnosis, treatment, and survival of older adults with colon cancer. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:1268–1273.

- Cunningham R, Sarfati D, Stanley J, et al. Cancer survival in the context of mental illness: a national cohort study. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2015;37:501–506.

- Kisely S, Sadek J, MacKenzie A, et al. Excess cancer mortality in psychiatric patients. Can J Psychiatry. 2008;53:753–761.

- Lawrence D, Holman CD, Jablensky AV, et al. Excess cancer mortality in Western Australian psychiatric patients due to higher case fatality rates. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2000;101:382–388.

- Batty GD, Whitley E, Gale CR, et al. Impact of mental health problems on case fatality in male cancer patients. Br J Cancer. 2012;106:1842–1845.

- Chang CK, Hayes RD, Broadbent MT, et al. A cohort study on mental disorders, stage of cancer at diagnosis and subsequent survival. BMJ Open. 2014;4:e004295.

- Osborn DP, Limburg H, Walters K, et al. Relative incidence of common cancers in people with severe mental illness. Cohort study in the United Kingdom THIN primary care database. Schizophr Res. 2013;143:44–49.

- Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care. 2005;43:1130–1139.

- Allison PD. Survival analysis using the SAS system: a practical guide. Cary (NC): SAS Institute Inc.; 1995. p. 247–249.

- Virtanen T, Eskelinen S, Sailas E, et al. Dyspepsia and constipation in patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Nord J Psychiatry. 2017;71:48–54.

- De Hert M, Hudyana H, Dockx L, et al. Second-generation antipsychotics and constipation: a review of the literature. Eur Psychiatry. 2011;26:34–44.

- Federico A, Cotticelli G, Festi D, et al. The effects of alcohol on gastrointestinal tract, liver and pancreas: evidence-based suggestions for clinical management. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2015;19:1922–1940.

- Sharma A, Jamal MM. Opioid induced bowel disease: a twenty-first century physicians dilemma. Considering pathophysiology and treatment strategies. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2013;15:334.

- Malik Z, Baik D, Schey R. The role of cannabinoids in regulation of nausea and vomiting, and visceral pain. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2015;17:429.

- Lee MG, Chiu CC, Wang CC, et al. Trends and outcomes of surgical treatment for colorectal cancer between 2004 and 2012 – an analysis using National Inpatient Database. Sci Rep. 2017;7:2006.

- Vuorenkoski L, Mladovsky P, Mossialos E. Finland: health system review. Health systems in transition. United Kingdom: WHO; 2008.

- Hermanson T, Vertio H, Mattson J. Development of cancer treatment in 2010–2020. Working group report. Ministry of Social Affairs and Health. Report No 6, 2010. Available from: http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-952-00-2971-5.

- ANCR. Survey of Nordic cancer registries. pp. 1–261. Danish Cancer Society; 2000. p. 1–261 Available from: http://www.ancr.nu/survey.asp.

- Leinonen MK, Miettinen J, Heikkinen S, et al. Quality measures of the population-based Finnish Cancer Registry indicate sound data quality for solid malignant tumours. Eur J Cancer. 2017;77:31–39.

- Pukkala E, Engholm G, Højsgaard Schmidt LK, et al. Nordic Cancer Registries - an overview of their procedures and data comparability. Acta Oncol. 2017 [cited 2017 Dec 11]; [16 p.]. DOI:10.1080/0284186X.2017.1407039

- Robinson D, Sankila R, Hakulinen T, et al. Interpreting international comparisons of cancer survival: the effects of incomplete registration and the presence of death certificate only cases on survival estimates. Eur J Cancer. 2007;43:909–913.

- Sund R. Quality of the Finnish Hospital Discharge Register: a systematic review. Scand J Public Health. 2012;40:505–515.

- Lahti R. From findings to statistics: an assessment of Finnish medical cause-of-death information in relation to underlying-cause coding [dissertation]. Helsinki: Department of Forensic Medicine, University of Helsinki; 2005.

- StatFin database. Autopsies by age in 1975–2014. Helsinki: Statistics Finland; [Internet] 2016. Available from: http://pxnet2.stat.fi/PXWeb/pxweb/fi/StatFin/StatFin__ter__ksyyt/?tablelist=true&rxid=b94b307b-a1ad-4fed-9ff0-29b3bddd02e4.

- Suvisaari J, Perälä J, Saarni SI, et al. The epidemiology and descriptive and predictive validity of DSM-IV delusional disorder and subtypes of schizophrenia. Clinical Schizophrenia & Related Psychoses. 2009;2:289–297.

- Perälä J, Suvisaari J, Saarni SI, et al. Lifetime prevalence of psychotic and bipolar I disorders in a general population. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:19–28.

- Isohanni M, Mäkikyrö T, Moring J, et al. A comparison of clinical and research DSM-III-R diagnoses of schizophrenia in a Finnish national birth cohort. Clinical and research diagnoses of schizophrenia. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1997;32:303–308.