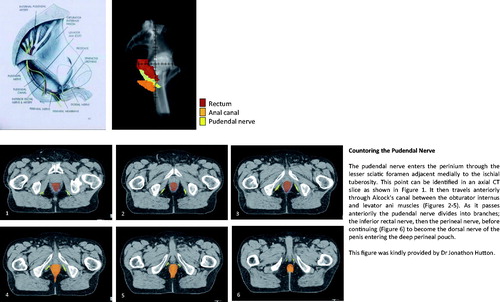

The first author of the enclosed article [Citation1], Eric Yeoh, has for several decades provided information for our understanding of the pathophysiological processes that ultimately decrease bowel health in cancer survivors. He continues to provide cutting-edge knowledge; the enclosed article shows a way to move forward. Treating the pudendal nerves as risk organs during dose planning and implementing dose constraints will decrease the occurrence and severity of the fecal-leakage syndrome in survivors who have received irradiation for a cancer in the pelvic cavity [Citation2,Citation3]. The fecal-leakage syndrome increases with time to follow-up and must be considered as life-long [Citation4]. The enclosed figure, provided by one of the authors, Jonathon Hutton, shows how to contour the nerves in clinical practice.

In the article [Citation1], the metric for pudendal-nerve function is pudendal-nerve terminal-motor latency. The authors describe how they measure this factor and set a cut-off for pathological function. By applying that cut-off, they find a five-fold increased prevalence (53 vs. 10%) of pudendal-nerve dysfunction among prostate-cancer survivors who had undergone radiotherapy as compared with matched non-irradiated controls. Pudendal-nerve dysfunction may cause fecal leakage. Moreover, in addition to providing impulses to the anal sphincters the pudendal nerves also provide impulses to part of the vagina; limiting the dose may also result in providing better female sexual health in gynecological-cancer survivors (albeit not mentioned by the authors).

The authors furthermore report that the internal anal sphincter on average is 0.5 mm thinner and the external anal sphincter 1.3 mm thinner among prostate-cancer survivors than among non-irradiated matched controls. As Eric Yeoh has argued before, we should contour the anal-sphincter region separately from the rectum during dose-planning. The pathophysiological processes that make the sphincters thinner and ultimately lead to a fecal-leakage syndrome probably differ to some part or entirely from those leading to fecal-urgency syndrome (e.g., stem-cell death giving a crypt degeneration that ultimately leads to a fibrotic and dysfunctional gut wall and a disturbed function of the microbiota) [Citation5,Citation6]. The distinction is crucial in both a clinical and a scientific context.

Important for the contributions from Eric Yeoh is his early collaboration with Robert Fraser, a gastroenterologist. The current publication in Acta Oncologica [Citation1] is preceded by a long list of contributions from this cooperation [Citation7–9]. Wanting to understand the real problems and their impact on the life of the cancer survivors, Eric Yeoh and Robert Fraser worked together to find ways forward and focused with time on the pudendal nerves. The early years of this pioneering work coincided with a time when there were cultural taboos concerning talking about feces; it was a time when articles downplayed the life-long suffering among cancer survivors and when abstract terms such as grade-1 toxicity concealed the truth. Today, we have articles, which document that when a survivor experiences being the source of fecal odor and senses anal leakage, this certainly compromises the survivor’s full possibilities to experience the pleasures of life [Citation10].

Hopefully, within a short period we can get data from other groups that address the findings by Yeoh and coworkers. With more data we can increase the precision concerning dose constraints to the pudendal nerves and possibly also identify modifying factors. We do not need to start a longitudinal study today and wait; our starting point can be the 1990s with follow-up today [Citation11]. Dose plans in many centers have been stored electronically and can be reactivated. On the reactivated dose plans, the pudendal nerves can be delineated by applying today’s up-to date anatomical-radiological understanding (). It is possible to link these dose–volume data to current intensity of the fecal-leakage syndrome (as well as sexual health). That is, prediction models can be produced in which doses to different volumes of the pudendal nerves are related to the syndrome. The validity of such studies is as good as if we had delineated the nerves in the first place during the 1990s and waited until today to assess patient-reported outcomes and signs.

Figure 1. Countoring the pudendal nerve. The pudendal nerve enters the perinium through the lesser sciatic foramen adjacent medially to the ischial tuberosity. This point can be identified in an axial CT slice as shown in (1). It then travels anteriorly through Alcock's canal between the obturator internus and levator ani muscles (2–5). As it passes anteriorily the pudendal nerve divides into branches; the inferior rectal nerve, then the perineal nerve, before continuing (6) to become the dorsal nerve of the penis entering the deep perineal pouch. This figure was kindly provided by Dr Jonathon Hutton

Moreover, members of the author group show in separate articles that the colon moves in retrograde direction, possibly helping us to reabsorb fluid [Citation12–14]. Dysfunction of this ‘large-bowel brake’ may be important for contracting the urgency syndrome. In the years to come, we can expect additional knowledge from the groups in Adelaide and Auckland meeting the ultimate goal of curing cancer with irradiation while restoring bowel health in the survivors.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Yeoh EE, Botten R, Di Matteo A, et al. Pudendal nerve injury impairs anorectal function and health related quality of life measures ≥2 years after 3D conformal radiotherapy for prostate cancer. Acta Oncol. 2017 [Nov 15]: [1–9]. DOI:10.1080/0284186X.2017.1400690.

- Yeoh EK, Holloway RH, Fraser RJ, et al. Pathophysiology and natural history of anorectal sequelae following radiation therapy for carcinoma of the prostate. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;84:e593–e599.

- Loganathan A, Schloithe AC, Hutton J, et al. Pudendal nerve injury in men with fecal incontinence after radiotherapy for prostate cancer. Acta Oncol. 2015;54:882–888.

- Steineck G, Sjöberg F, Skokic V, et al. Late radiation-induced bowel syndromes, tobacco smoking, age at treatment and time since treatment - gynecological cancer survivors. Acta Oncol. 2017;56:682–691.

- Bull CM, Malipatlolla D, Kalm M, et al. A novel mouse model of radiation-induced cancer survivorship diseases of the gut. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2017;313:456–466.

- Steineck G, Schmidt H, Alevronta E, et al. Toward restored bowel health in rectal cancer survivors. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2016; 26:236–250.

- Fraser R, Frisby C, Schirmer M, et al. Effects of fractionated abdominal irradiation on small intestinal motility–studies in a novel in vitro animal model. Acta Oncol. 1997;36:705–710.

- Yeoh EK, Russo A, Botten R, et al. Acute effects of therapeutic irradiation for prostatic carcinoma on anorectal function. Gut. 1998;43:123–127.

- Yeoh EE, Botten R, Russo A, et al. Chronic effects of therapeutic irradiation for localized prostatic carcinoma on anorectal function. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2000;47:915–924.

- Alsadius D, Olsson C, Pettersson N, et al. Perception of body odor-an overlooked consequence of long-term gastrointestinal and urinary symptoms after radiation therapy for prostate cancer. J Cancer Surviv. 2013;7:652–658.

- Alevronta E, Åvall-Lundqvist E, Al-Abany M, et al. Time-dependent dose-response relation for absence of vaginal elasticity after gynecological radiation therapy. Radiother Oncol. 2016;120: 537–541.

- Yeoh EK, Bartholomeusz DL, Holloway RH, et al. Disturbed colonic motility contributes to anorectal symptoms and dysfunction after radiotherapy for carcinoma of the prostate. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;78:773–780.

- Lin AY, Dinning PG, Milne T, et al. The “rectosigmoid brake”: review of an emerging neuromodulation target for colorectal functional disorders. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2017;44: 719–728.

- Lin AY, Du P, Dinning PG, et al. High-resolution anatomic correlation of cyclic motor patterns in the human colon: evidence of a rectosigmoid brake. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2017;312:G508–GG15.