Abstract

Objective: Cancer and its treatment have an influence on health-related quality of life (HRQOL). Normative data could help to interpret HRQOL among cancer patients. Our aim was to generate longitudinal normative data based on sex, age and morbidity for the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) QLQ-C30 questionnaire.

Methods: The QLQ-C30 and the Self-administered Comorbidity Questionnaire were administered to a representative panel of the Dutch-speaking population in the Netherlands in 2009 (n = 1743), 2010 (n = 2050), 2011 (n = 2040), 2012 (n = 2194) and 2013 (n = 2333).

Results: Regarding sex, at baseline, women scored statistically significant and clinically relevant worse on fatigue, pain and insomnia compared to men. Regarding age groups and sex, HRQoL was lower among the older age groups in men and women. For men, at baseline, significant and clinically relevant age differences were found on physical, role and cognitive functioning, global QOL scale, fatigue, pain and dyspnea. The change over 5 years was larger for older age groups. For women, at baseline, significant and clinically relevant age differences were found on physical functioning, role functioning, nausea/vomiting, pain, dyspnea and insomnia. Those without self-reported morbidities reported a better HRQoL compared to those with morbidities. Among those who completed five assessments, the summary scale scores were stable over time, were higher in men than in women, and higher in younger compared to older age groups.

Conclusions: Although HRQoL remains relatively stable over time, HRQoL data needs to be interpreted with care as many confounding factors can have an impact on HRQOL. Our data (which is freely available) can aid in the interpretation of QLQ-C30 scores and can help increase our understanding of the influence of age, sex, time and morbid conditions on HRQoL among cancer patients.

Introduction

The assessment of health-related quality of life (HRQOL) among cancer patients has gained importance over the past decades and is now considered to be standard in most clinical studies. One of the most widely used questionnaires to assess HRQOL is the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire C30 (EORTC QLQ-C30) [Citation1]. This questionnaire was developed by the EORTC to assess HRQOL of cancer patients and it can be supplemented by disease-specific modules. The QLQ-C30 has good psychometric properties and is responsive to change [Citation1,Citation2]. A quick search of the literature on PubMed shows that at least 2500 publications report on this questionnaire and it has been translated and validated in over a 100 languages [Citation3].

Although the QLQ-C30 is being used repeatedly to assess HRQOL, and the clinically relevant differences in QLQ-C30 scores between and within subjects have been established [Citation4,Citation5], its interpretation is at times challenging due to the lack of cutoff points for ‘low’, ‘acceptable’ or ‘good’ HRQOL [Citation6]. Yet, it is almost impossible to make these distinctions since HRQOL differs tremendously across individuals and situations. This makes the interpretation of HRQOL more difficult compared to, for instance, the interpretation of depression scores in which cutoffs have been established [Citation7]. Also, a true baseline assessment of HRQOL before diagnosis and treatment of cancer is almost always lacking. The availability of QLQ-C30 reference data from general population samples improved its interpretability tremendously. Reference data is now available for an increasing number of, mostly European, countries [Citation8–10]. With reference data, one can compare HRQOL scores of a certain cancer patient sample to age- and sex-matched normative data from the general population without cancer in order to see the true effect of cancer and its treatment. Together with the established clinically important differences by Cocks et al. [Citation4] (e.g., the smallest difference that patients notice and perceive as moderately beneficial), this allows researchers to estimate whether HRQOL differs between cancer patients and the general population in a clinically meaningful way. In order to make proper comparisons with cancer patient populations’ possible, reference data is preferably presented according to age, sex and morbid conditions, since they have a profound impact on HRQOL [Citation6,Citation11].

Although some studies compared reference data between populations of different countries [Citation9,Citation10,Citation12,Citation13], or between different samples over time in a single country [Citation10,Citation11], longitudinal normative data on the QLQ-C30 has not been reported previously in the literature. The availability of longitudinal QLQ-C30 normative data could enhance the interpretation of longitudinal studies among cancer patients since it helps interpreting whether changes in HRQOL are due to cancer or to ageing and the presence of morbidity. Therefore, our primary aim was to present Dutch normative data for the QLQ-C30 collected in five consecutive years. We also present normative data for different subsamples by stratifying the total sample by sex, age and morbid conditions.

Material and methods

Setting and study population

Normative data were derived from the Health and Health Complaints project from CentERdata (www.centerdata.nl). In short, CentERdata has an online household panel (i.e., the CentERpanel) which consists of about 2000 households. This panel is representative of the Dutch-speaking population in the Netherlands, including those without Internet access. The latter are provided with broadband access and a personal computer. Members of the CentERpanel of 18 years and older completed the QLQ-C30. This sample has been described previously [Citation14].

The initial CentERpanel sample was drawn in cooperation with Statistics Netherlands (CBS), by Random Digit Dialling. In order to be able to compensate for potential attrition during the four-year assessment, a reserve pool of panel members were gathered by selecting a random sample of addresses from a mailing addresses database. Then, a random sample of potential new members was interviewed by telephone or by mail. If the person was willing to participate in survey research, the household was included in a database of potential panel members. In case a participating household drops out of the panel, a new household is selected from this database based on demographic characteristics in order to maintain a representative panel of the adult, Dutch-speaking population.

Panel members received online questionnaires in November 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012 and 2013. Nonrespondents were reminded a week later.

Study measures

Sociodemographic data that were collected include age, gender, living situation (with partner and/or children), education, income, work situation and degree of urbanization of residence.

HRQOL was assessed with the Dutch version of the EORTC QLQ-C30 (Version 3.0) [Citation1]. It contains five functional scales on physical, role, cognitive, emotional and social functioning, a global QOL scale, three symptom scales on fatigue, nausea/vomiting, pain and six single items assessing dyspnea, insomnia, loss of appetite, constipation, diarrhea and financial impact. Each item is scored on a four-point Likert-scale, except the global QOL scale, which has a seven-point Likert-scale. Scores were linearly transformed to a 0–100 scale [Citation15]. Besides the global QOL scale, a single higher-order summary score was calculated, using 27 out of the 30 items (excluding global quality of life and financial impact) [Citation16,Citation17]. A higher score on the functional scales, the global QOL scale and summary score means better functioning and HRQOL, whereas a higher score on the symptom scales means more complaints. Though this questionnaire was developed for cancer patients, the questions are appropriate for any respondent, as they are quite general. Examples of questions are; ‘Do you have any trouble taking a long walk?’ (physical functioning scale), ‘Have you vomited?’ (nausea/vomiting symptom scale) and ‘Have you had trouble sleeping?’ (insomnia single item).

Self-reported morbid conditions were assessed with an adapted Self-administered Comorbidity Questionnaire (SCQ) [Citation18]. Patients were asked whether they currently had asthma/COPD, depression, diabetes mellitus, heart disease, hypertension, osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, stroke, stomach-, kidney- or liver-disease and thyroid condition or whether they had had any of these conditions in the past 12 months. Information on whether they had cancer in the past was obtained via a separate question.

Statistical analyses

Routinely collected data from the CentERpanel on panel characteristics enabled us to compare the group of nonrespondents with respondents, using analysis of variance (ANOVAs) for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables. The same tests were used to analyze sociodemographic differences between participants who completed only one questionnaire and those who completed two or more questionnaires and to compare participant characteristics according to sex.

For purposes of comparison with other studies, mean scores are reported in 10-year age groups for men and women separately, with the exception of the youngest (18–29 year) and oldest age groups (70–92 year) due to small numbers. ANOVAs were conducted to assess differences in EORTC QLQ-C30 scores by sex, by age groups and sex and by self-reported morbidities in (1) mean EORTC baseline subscale scores; (2) mean change scores per year (first the change scores between two consecutive time points were calculated and second the mean of the total of change scores was calculated, only for patients who completed at least two questionnaires) and (3) change scores over 5 years (defined as the change between T1 and T5).

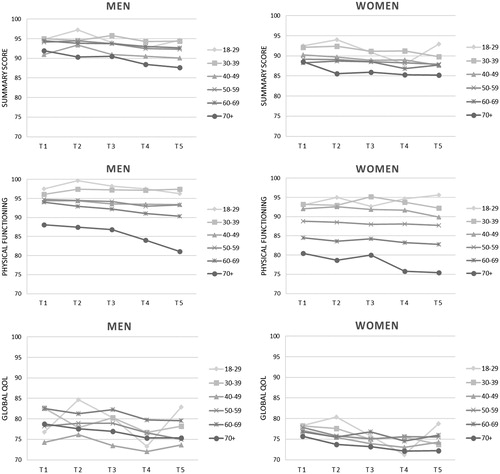

For patients who completed all five questionnaires, we graphically present mean scores over time for three scales: physical functioning, global quality of life and the EORTC summary score. The global quality of life scale is the most commonly reported scale, the physical functioning scale is recommended by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as the sole functional outcome [Citation19], while the overall summary score encompasses both functioning and symptoms and might therefore be most reliable [Citation16,Citation20].

Analyses were performed in IBM SPSS 24.0 (IBM SPSS Statistics, Armonk, NY, USA) and we used a significance level of α = .05. Clinically meaningful differences between QLQ-C30 baseline scores were determined using the guidelines for interpretation of the QLQ-C30 ‘between groups’ [Citation4]. Since a guideline for the interpretation of the emotional functioning scale and summary score was lacking from these guidelines [Citation4], we used the guideline for the role functioning scale instead because this one is the strictest. ‘Within a group’, clinical relevant differences over time were defined as a 10 point or more difference [Citation5].

Participants characteristics are provided for all participants in , only those that completed at least two questionnaires were included in further analyses, only those that completed the first and the last questionnaire were included in the 5-year change scores. The results will be discussed per subgroup.

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics of the sample from the Health and Health Complaints project of CentERdata at T1.

Results

Sample characteristics

Questionnaires were filled out by participants from the CentERpanel in 2009 (n = 1743), 2010 (n = 2050), 2011 (n = 2040), 2012 (n = 2194) and 2013 (n = 2333). Of the 3483 individuals that completed a questionnaire during the 5 years of the study, 1197 individuals responded to both the 2009 and 2013 questionnaire (34.4%), 967 individuals filled out all questionnaires (27.8%) and 2539 filled out at least two questionnaires in time (72.9%).

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of respondents at T1

The group of respondents at baseline (i.e., the first questionnaire of a participant, whether it was 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012 or 2013) consisted of 1364 men and 1193 women with a mean age of 52.3 (). The women were significantly younger (p < .001), more often single (with or without children; p < .0001) and lower educated (p < .0001). Men were more often working or retired (p < .001) and reported a higher family income (p < .001). No differences between men and women were found regarding urbanization.

Regarding self-reported morbidities as assessed with the adapted SCQ, 40.5% (n = 392) of the respondents reported no morbid conditions in the past 12 months. A self-reported cancer diagnosis was present in 7% of the participants. Men more often reported having been diagnosed with heart disease (12 vs. 4.2%; p < .001) in the past 12 months compared to women, and they less often reported a diagnosis of anemia (1.1 vs. 3.7%; p = .008), thyroid disease (1.1 vs. 4.9%; p < .001), depression (3.2 vs. 7.2%; p = .04), rheumatoid arthritis (3.5 vs. 7.7%; p < .001) and osteoarthritis (14 vs. 24%; p < .0001).

Differences between respondents who completed one or at least two questionnaires

In comparison with those who filled out one questionnaire, those who filled out at least two were older (52.3 years vs. 42.1 years; p < .0001), more often male (53% male vs. 48% male; p < .001), retired (24.1% retired vs. 12.3% retired; p < .0001), had a lower monthly net income (€1644.7 vs. €1766.1; p < .001), lower educated (high school or lower 43.5 vs. 33.1%; p < .0001), more often single (22.1% single vs. 17.6% single; p < .0001) and had fewer people in their household (2.5 vs. 2.8; p < .0001). Also, they reported more morbid conditions (1.1 vs. 0.6; p < .0001). Specifically, they were more often diagnosed with cancer (7.3% vs.5.25; p < .05), a heart condition (8.5% vs. 4.4%; p < .0001), high blood pressure (21% vs. 11.1%; p < .0001), diabetes (6.1% vs. 2.6%; p < .0001), osteoarthritis (15.1 vs. 9.0 p < .0001) and rheumatoid arthrosis (4.9% vs. 2.0%; p < .0001). With respect to the QLQ-C30, those who filled out at least two questionnaires reported lower scores on fatigue (mean 17.4 vs. 20.8; p < .0001) and appetite loss (3.2 vs. 4.5; p < .01), and higher scores on emotional functioning (88.8 vs. 84.8; p < .0001) compared to people who completed one questionnaire. However, these differences were not clinically relevant.

EORTC QLQ-C30 by sex

From this point forward, only those that completed at least two questionnaires were included in our analyses. At baseline, women scored statistically significantly worse on all functioning scales, the global QOL scale and summary scale, all symptoms scales and all single items compared to men except for diarrhea (all p’s < .0001; ). This was only clinically relevant for fatigue, pain and insomnia. Furthermore, women showed a significantly lower mean change per year on physical functioning (p < .0001), the summary score (p < .05) and fatigue (p < .001) but this was not clinically relevant. Finally, no significant differences were found between men and women regarding their change over 5 years.

Table 2. Mean baseline and change scores (standard deviations in parentheses) of EORTC QLQ-C30.

EORTC QLQ-C30 by age groups and sex

Scores slightly fluctuated but in general HRQoL was lower among the older age groups. For men, at baseline, significant age differences were found on physical, role, emotional, cognitive and social functioning, the global QOL scale, the summary score, fatigue, pain, dyspnea and constipation (). The differences in physical, role and cognitive functioning, global QOL scale, fatigue, pain and dyspnea were clinically relevant. For men, mean change per year was higher among older age groups for physical functioning (p = .041) but this was not clinically relevant. The change over 5 years was larger for older age groups for physical functioning (p < .0001), the summary score (p = .035) and insomnia (p = .045) among men but this was not clinically relevant.

For women, at baseline, significant age differences were found on physical functioning, role functioning, the summary score, nausea/vomiting, pain, dyspnea and insomnia (). These differences were all clinically relevant except for the summary score. Moreover, mean change per year for women was higher among older age groups for physical functioning (p = .03) and fatigue (p = .041) but this was not clinically relevant. Lastly, no changes between age categories were found in 5 years change scores among women.

EORTC QLQ-C30 by age groups and sex over time

Among those who completed five assessments, the scores on the physical functioning scale and the summary scale were quite stable over time within the different age categories (). However, there was a clear decrease in the oldest age group (70+) over the five-year period. The scores on the global QOL scale were less stable and fluctuated more over time within most age categories between both men and women. Furthermore, the scores on the global QOL scale, the physical functioning scale and the summary scale were higher in men than in women and higher in the younger age groups compared to the older age groups.

EORTC QLQ-C30 by self-reported morbid conditions

At baseline, respondents with asthma/COPD, joint disease and depression reported a significantly worse HRQoL on almost all scales and single items compared to those without any morbid conditions (except on appetite loss among those with joint disease and diarrhea among those with joint disease and depression) (). Those with heart disease, hypertension or diabetes now or in the past 12 months reported a lower HRQOL on some of the QLQ-C30 subscales and items. Those ever diagnosed with cancer also reported a lower HRQOL on some QLQ-C3- subscales and items. These differences were all clinically relevant except constipation among asthma/COPD patients and appetite loss among cancer patients. No clinically relevant differences were found regarding mean change per year and the change over 5 years.

Table 3. Mean baseline and change scores (standard deviations) of EORTC QLQ-C30.

Discussion

Results of this 5-year longitudinal study among the general Dutch population showed that at baseline, women scored statistically significant and clinically relevant worse on fatigue, pain and insomnia compared to men. Regarding age groups and sex, HRQoL was lower among the older age groups in men and women. For men, at baseline, significant and clinically relevant age differences were found on physical, role and cognitive functioning, global QOL scale, fatigue, pain and dyspnea. For women, at baseline, significant and clinically relevant age differences were found on physical functioning, role functioning, nausea/vomiting, pain, dyspnea and insomnia. Those without self-reported morbidities reported a better HRQoL compared to those with morbidities. Among those who completed five assessments, the summary scale scores were stable over time, were higher in men than in women, and higher in younger compared to older age groups.

Women reported a worse HRQoL compared to men, which is in line with other studies [Citation9,Citation13,Citation21–23]. However, women reported a significantly lower mean difference per year on physical functioning, the summary score and fatigue compared to men. Probably, because they reported a worse HRQOL than men from the start. Nevertheless, no significant differences were found between men and women regarding their change in 5 years.

In general, HRQOL was lower among the older age groups in both men and women which was also found in previous studies [Citation9,Citation13,Citation21–23]. Furthermore, change scores were higher in physical functioning per year in the older age groups indicating faster decrease. Similar data has not been reported previously on this topic. Our results might, at least partially, be explained by the general increase in morbid conditions that is associated with age.

As we reported previously [Citation12], the EORTC QQL-C30 is perfectly able to discriminate between those with and without self-reported morbid health conditions. In general, those with chronic health conditions reported a significantly lower HRQoL, than those without such conditions. This finding confirms the results of a Norwegian and Swedish study [Citation23,Citation24]. Also, a study among the general Korean population showed that an increase in the number of somatic diseases was associated with lower QLQ-C30 scores [Citation9]. Overall, QLQ-30 reference data among those with various morbid conditions is valuable for use in studies including cancer patients, since they often have morbid conditions. Especially long after the diagnosis of cancer, the morbid condition or its treatment can be more strongly related to a patients’ HRQOL than cancer itself.

This study had a number of limitations. For instance, our normative data did not include many elderly while the prevalence of cancer increases with age. In a new study, we will solve this by oversampling elderly persons. Also, our data was collected in the Netherlands, which is a relatively rich and prosperous country with excellent access to affordable and high quality health care. Results are therefore only representative for western countries at best while comparison with other countries is difficult. In addition, we found differences in age, sex, work, education, income, marital status, household and morbid conditions between those who filled out one questionnaire versus those who filled out at least two, so this indicates possible response bias or selection bias. Furthermore, not all patients completed all assessments which could be a sign of selection bias. It is possible that only the healthiest participants had the energy to keep completing questionnaires every year. The other way around is also possible, perhaps only those with health complaints felt the need to report this year after year. Furthermore, our data on morbid conditions were self-reported which is less reliable compared to clinical examinations. One of the strengths of this study is the fact that this is the first study that presents longitudinal normative data collected over a period of 5 years. This provides insight into the natural course of HRQOL in the general population and is helpful in the interpretation of longitudinal QLQ-C30 data of cancer patients. In addition, the CentERpanel is not biased by socioeconomic status of computer literacy because all panel members were initially contacted by mail and phone, and those without internet/computer capabilities were provided with them. Another strength is the use of an online questionnaire which usually results in more complete data compared to paper and pencil questionnaires [Citation25] and does not decrease overall response rates [Citation26]. Finally, the raw normative data presented in this study is freely available for noncommercial research purposes via the PROFILES registry (see www.profilesregistry.nl for conditions of use). This enables researchers to select age-matched normative data suitable for their own research purpose.

In conclusion, our results demonstrate that HRQOL data needs to be interpreted with care as many confounding factors might have an impact on HRQOL. For instance, this article showed that there is an urgent need to include age, gender and morbidity into account when reporting on HRQOL outcomes. Of course, other background characteristics can be considered as well. In general, longitudinal population-based reference values are an important tool in the interpretation of HRQOL among cancer patients. They can be used to compare QoL-courses of cancer patients with normative data to investigate potential response shift in the cancer group. Also, they can be used to control for effects that arose by repeated assessment with the same instrument (e.g., habituation). The fact that QLQ-C30 scores were worse among those with morbid conditions may improve the understanding of the influence of comorbid health conditions on HRQOL among cancer patients. Our longitudinal reference data will hopefully facilitate better interpretation of QLQ-C30 results among cancer patients by providing age- and gender-specific norms and change scores from the general population. Besides its usefulness for research papers, our data can be used to offer feedback to patients on their HRQOL by giving a graphical overview of patients’ own scores (over time) in comparison with those of a normative population of the same age and sex (over time) [Citation27]. As this is the first publication on longitudinal reference data of the QLQ-C30, replication is recommended, especially in other countries.

| Abbreviations | ||

| EORTC QLQ-C30 | = | European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire C30 |

| SCQ | = | Self-administered Comorbidity Questionnaire |

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:365–376.

- Bjordal K, de Graeff A, Fayers PM, et al. A 12 country field study of the EORTC QLQ-C30 (version 3.0) and the head and neck cancer specific module (EORTC QLQ-H&N35) in head and neck patients. EORTC Quality of Life Group. Eur J Cancer. 2000;36:1796–1807.

- Webpage. EOfRatoc. http://groups.eortc.be/qol/eortc-qlq-c30 2017 [cited 2017 July 27].

- Cocks K, King MT, Velikova G, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for determination of sample size and interpretation of the European Organisation for the Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30. JCO. 2011;29:89–96. Epub 2010/11/26.

- Osoba D, Rodrigues G, Myles J, et al. Interpreting the significance of changes in health-related quality-of-life scores. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:139–144.

- Fayers PM. Interpreting quality of life data: population-based reference data for the EORTC QLQ-C30. Eur J Cancer. 2001;37:1331–1334.

- Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361–370.

- Finck C, Barradas S, Singer S, et al. Health-related quality of life in Colombia: reference values of the EORTC QLQ-C30. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2012;21:829–836.

- Yun YH, Kim SH, Lee KM, et al. Age, sex, and comorbidities were considered in comparing reference data for health-related quality of life in the general and cancer populations. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60:1164–1175.

- Hinz A, Singer S, Brahler E. European reference values for the quality of life questionnaire EORTC QLQ-C30: results of a German investigation and a summarizing analysis of six European general population normative studies. Acta Oncol. 2014;53:958–965.

- Juul T, Petersen MA, Holzner B, et al. Danish population-based reference data for the EORTC QLQ-C30: associations with gender, age and morbidity. Qual Life Res. 2014;23:2183–2193.

- van de Poll-Franse LV, Mols F, Gundy CM, et al. Normative data for the EORTC QLQ-C30 and EORTC-sexuality items in the general Dutch population. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47:667–675.

- Schwarz R, Hinz A. Reference data for the quality of life questionnaire EORTC QLQ-C30 in the general German population. Eur J Cancer. 2001;37:1345–1351.

- Mols F, van de Poll-Franse LV, Vreugdenhil G, et al. Reference data of the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) QLQ-CIPN20 Questionnaire in the general Dutch population. Eur J Cancer. 2016;69:28–38.

- Fayers P, Aaronson NK, Bjordal K. Group. ObotEQoL. The EORTC QLQ-C30 scoring manual. 3rd ed. Brussels: EORTC; 2001.

- Giesinger JM, Kieffer JM, Fayers PM, et al. Replication and validation of higher order models demonstrated that a summary score for the EORTC QLQ-C30 is robust. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;69:79–88.

- Gundy CM, Fayers PM, Groenvold M, et al. Comparing higher order models for the EORTC QLQ-C30. Qual Life Res. 2012;21:1607–1617.

- Sangha O, Stucki G, Liang MH, et al. The Self-Administered Comorbidity Questionnaire: a new method to assess comorbidity for clinical and health services research. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;49:156–163.

- Kluetz PG, Slagle A, Papadopoulos EJ, et al. Focusing on core patient-reported outcomes in cancer clinical trials: symptomatic adverse events, physical function, and disease-related symptoms. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22:1553–1558.

- Pagano l S, Gotay CC. Modeling quality of life in cancer patients as a unidimensional construct. Hawaii Med J. 2006;65:76–80, 2–5.

- Waldmann A, Schubert D, Katalinic A. Normative data of the EORTC QLQ-C30 for the German population: a population-based survey. PLoS One. 2013;8:e74149.

- Derogar M, van der Schaaf M, Lagergren P. Reference values for the EORTC QLQ-C30 quality of life questionnaire in a random sample of the Swedish population. Acta Oncol. 2012;51:10–16.

- Michelson H, Bolund C, Nilsson B, Brandberg Y. Health-related quality of life measured by the EORTC QLQ-C30–reference values from a large sample of Swedish population. Acta Oncol. 2000;39:477–484.

- Hjermstad MJ, Fayers PM, Bjordal K, et al. Using reference data on quality of life-the importance of adjusting for age and gender, exemplified by the EORTC QLQ-C30 (+3)). Eur J Cancer. 1998;34:1381.

- Kongsved SM, Basnov M, Holm-Christensen K, et al. Response rate and completeness of questionnaires: a randomized study of Internet versus paper-and-pencil versions. J Med Internet Res. 2007;9:e25.

- Horevoorts NJ, Vissers PA, Mols F, et al. Response rates for patient-reported outcomes using web-based versus paper questionnaires: comparison of two invitational methods in older colorectal cancer patients. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17:e111.

- Oerlemans S, Arts LP, Horevoorts NJ, et al. “Am I normal?” The wishes of patients with lymphoma to compare their patient-reported outcomes with those of their peers. J Med Internet Res. 2017;19:e288.