Abstract

Aim: Patients with rectal cancer may undergo treatment such as surgery and (chemo)radiotherapy. Before treatment, patients are informed of different options and possible side-effects. The aim of the study was to evaluate the patients’ experience of communication with healthcare personnel at time of diagnosis and after one year.

Method: A total of 1085 patients from Denmark and Sweden were included. They answered a detailed questionnaire at diagnosis and at the one year follow-up. Clinical data were retrieved from national quality registries.

Results: Response rates were 87% at baseline and 74% at one year. Overall the patients were very satisfied with the communication with healthcare personnel. However, some patients reported insufficient information regarding treatment options and possible side-effects. Only 32% (335/1050) and 24% (248/1053), respectively, stated that they were informed about possible sexual and urinary dysfunction before treatment.

Conclusions: Even though patients felt that they received insufficient information regarding side-effects on sexual and urinary function, they were generally satisfied with the communication with the healthcare personnel. Since overall satisfaction with the level of information was very high, it is unlikely that further information to patients with rectal cancer in the surgical and oncological settings will improve satisfaction with communication.

Introduction

The current treatment for rectal cancer may include radiotherapy, surgery and chemotherapy [Citation1]. Which treatment that will be offered to the patient is related to the tumour stage and is often decided in a multidisciplinary conference involving surgeons, oncologists, pathologists and radiologists. In the last decades, the patients have also been more actively involved in the decision-making process [Citation2].

The decision-making process consists of several items and is an important part in the patient-centred communication [Citation3–6]. One important aspect is to exchange information with the patient to facilitate shared decision-making. It has previously been shown that several anticipated benefits and harms related to the planned treatment should be addressed with patients newly diagnosed with rectal cancer [Citation7,Citation8]. Long-term altered defecation patterns, long-term faecal incontinence, erectile dysfunction, ejaculation disorder, vaginal dryness, pain during intercourse and infertility were included among the topics that both patients and clinicians agreed upon should be addressed [Citation9]. Most patients will experience some of these significant side-effects of the treatment and it may have an impact on the patients’ quality of life [Citation10–13]. Other important side-effects are cognitive dysfunction after chemotherapy [Citation14] and after anaesthesia and surgery [Citation15], and peripheral neuropathy [Citation16].

The primary aim of this study was to describe the patient-reported experience of communication with healthcare personnel at the surgical clinic during the first year after rectal cancer diagnosis. In addition, we wanted to describe the communication regarding treatment alternatives and potential side-effects of the planned treatment at baseline, at time of diagnosis, and at the one year follow-up.

Methods

The QoLiRECT (Quality of Life in RECTal cancer) patient cohort consists of patients with rectal cancer, prospectively included at 16 colorectal units in Denmark and Sweden, from 2012 to 2015. Patients younger than 18 years and patients who could not read or understand Swedish or Danish were excluded. Questionnaires were administered to the patient at four time-points: first at inclusion, when the patient had been informed of the diagnosis and planned treatment, and then after one, two and five years. The present analyses are based on data collected at baseline and at the one year follow-up as well as on clinical data from the Danish and Swedish national quality registries.

The questionnaires were developed according to a well-established method [Citation17]. The baseline questionnaire included questions based on semi-structured interviews with patients that recently had been diagnosed with rectal cancer, but had not begun the treatment. The questionnaire at the one year follow-up included questions based on semi-structured interviews with patients one year after they received the rectal cancer diagnosis. During the semi-structured interviews patients were asked to speak freely regarding their experience of their diagnosis, treatment and the time up to one year after treatment and were asked supporting questions to ascertain that the patients did not omit relevant topics. A content analysis of the interviews was performed to clarify themes of interest which could be used to construct questions using a ‘one problem – one question’ approach. The questions were then face-to-face validated. The final questionnaire include questions specific to rectal cancer and pre-validated questions used in other studies as well as the EQ-5D-3L [Citation18], and the 29-item Sense of Coherence scale (SOC-29) [Citation19]. Further details of the protocol and the development of the study specific questionnaires have been described previously [Citation20].

Outcome measures

The objective was to describe the patient-reported experience on communication with healthcare personnel at the surgical clinic during the first year after diagnosis. Both the general communication and the communication regarding potential side-effects of the treatments were assessed by several questions. For example, the patients’ experience of the communication with the physician at the surgical clinic was assessed using the question Was the communication with the physicians at the surgical clinic good? where the response categories were No, Yes, quiet and Yes, very at baseline and Not applicable, Yes, No, and Neither yes nor no at the one year follow-up. Regarding potential side-effects of treatments the question at baseline was Have you and your physician talked about the possible effects of the proposed treatment on the urinary tract? at baseline, with response categories Yes and No. The palliative patients’ experience of the communication with the healthcare personnel was also described. All questions used in the analyses are presented in Supplement 1.

Statistical methods

Patients’ experiences were summarized by number and per cent in the different response categories and presented graphically. Eligible patients are those who visited the surgical or oncological clinic. Patients who had not visited a surgical or oncological clinic, thus responding ‘Not applicable’, were not included in the evaluation of the one year follow-up data. Analysis of missing data was performed. Data were analysed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 25 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Ethical aspects

The QoLiRECT-study was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01477229). The Ethical Review Board of Gothenburg approved the study, registration number 595-11, and the study was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency (2007-58-0015/HEH.750.89.21). Permissions to use the EQ-5D-3L and Sense of Coherence Scale (SOC-29) were obtained.

Results

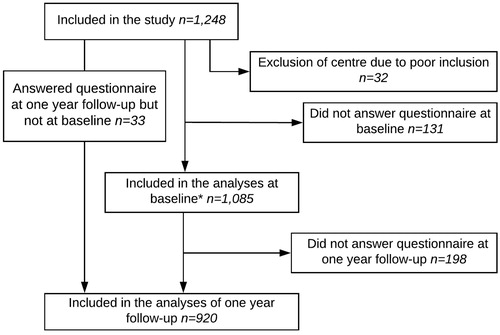

By assessing external validity we found that patients in the study cohort were one year younger, with somewhat less comorbidity and slightly lower tumour stage than non-included patients at the participating departments () [Citation21]. Response rates for the questionnaires at baseline and at the one year follow-up were 87% and 74%, respectively (). At the one year follow-up, 49 of the 198 non-responders were deceased (). Patients who answered the baseline questionnaire, but not the one year follow-up questionnaire, had more comorbidity (reflected by higher ASA, American Society of Anaesthesiology classification, grade) and more often had a more advanced tumour stage (higher Union for International Cancer Control, UICC, grade) than patients who answered both ().

Figure 1. Flow chart of patients included in the analyses at baseline and at the one year follow-up. Please note that 33 patients answered the questionnaire at the one year follow-up, but not at baseline. One centre was excluded due to poor inclusion. *Baseline questionnaires were distributed after diagnosis, prior to start of treatment.

Table 1. Demographics and clinical data for patients in the QoLiRECT patient cohort at baseline, after diagnosis prior to treatment.

Table 2. Description of all the patients (n = 198) and a subgroup analysis of the patients with palliative treatment (n = 37) that answered the baseline questionnaire but did not answer the questionnaire at the one year follow-up.

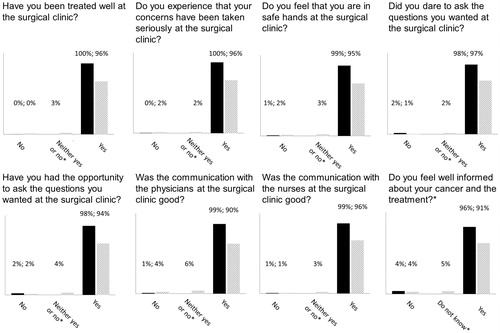

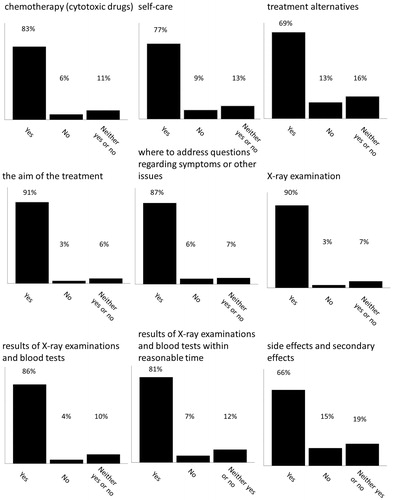

The rates of satisfaction were overall high and comparable between baseline and the one year follow-up ( and ). A majority of the patients reported that they felt that they had received adequate information about chemotherapy; however, some patients reported that they lacked information regarding general treatment alternatives and side-effects (31% and 44%, respectively) ().

Figure 2. Descriptive data of the patients’ experience of the overall communication at the surgical clinic over time, by repeated measures. Black indicates baseline (n = 1085) and grey (n = 920) the one year follow-up. *‘Neither yes nor no’ and ‘Do not know’ where only used as an answer alternative in the one year follow-up questionnaire.

Figure 3. Descriptive data of patients’ (n = 920) assessments of sufficient information regarding the specified subjects at the one year follow-up.

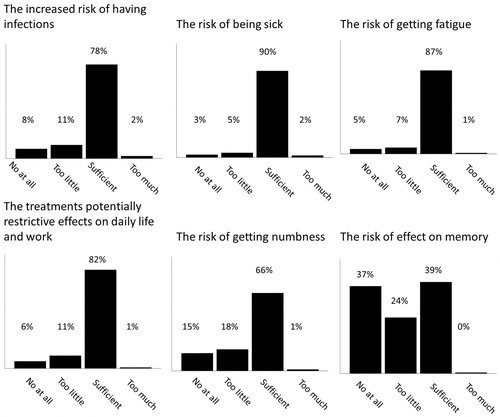

Among patients receiving chemotherapy, the majority were satisfied with the information. However, few patients experienced that they had been informed about possible cognitive side-effects and peripheral neuropathy after chemotherapy (). In general, patients remembered being well-informed about the possible side-effects on bowel function of the planned treatment (). Few patients stated that they remembered that they had talked with their physician about how the planned treatment might affect the urinary tract and sexual function ().

Figure 4. Descriptive data of the patients’ assessments of the received information regarding potential side-effects of chemotherapy. Data were collected from the questionnaire distributed one year after diagnosis.

Table 3. Descriptive data of number of patients that stated they talked with their physician about the planned treatment’s possible effects on anatomy and functionality.

In general, patients with palliative treatment experienced the communication at the oncological clinic as good (). None of the patients responded ‘No’ to the questions stated in . Before start of treatment 73 patients scheduled for treatment with palliative intent were included, at the one year follow-up 20 were deceased and 17 had not returned the questionnaire, leaving 36 patients to be included in the one year follow-up analyses.

Table 4. Descriptive data of the patients with palliative care (n = 42) experience of the overall communication at the oncological clinic.

Discussion

The results of our analyses suggest that although patients with rectal cancer experienced the communication with the healthcare personnel as very good. But they did not recollect having received sufficient information, as reported by themselves, regarding alternative treatment options and potential side-effects of the treatments.

In general, patients were very satisfied with the communication both at diagnosis and at the one year follow-up. This is in contrast to previous studies reporting much more dissatisfaction with information and the possibility to ask questions [Citation22]. It is difficult to explain this difference, it is possible that the fact that the time period in the earlier study including patients almost 15 years prior to our study has had an impact on the results. In general, medical education has focussed more on developing communication skills in the last two or three decades, and perhaps this influence the results? However, this is merely a speculation. Still, in daily clinical practice, insufficient information to patients with cancer seems to be a common phenomenon [Citation7, Citation23, Citation24]. There are ongoing efforts to improve information for patients with rectal cancer to aid them in the decision-making process [Citation25, Citation26]. However, in our study patients reported very good communication even though they reported insufficient information regarding urinary and sexual functional outcome after treatment. Of course, this may be due to recall bias, but it still did not affect the patients’ own experience of the communication. Nevertheless, as patients reported somewhat insufficient information regarding potential side-effects of the planned treatment, additional pre-treatment information may be a goal for future quality interventions to improve shared decision-making. Shared decision-making is slowly being a prerequisite in healthcare [Citation6] and will probably be a patient demand in the future. However, not all studies can show that patients want to participate, and perhaps this can explain that patients still reported a very high satisfaction level despite these gaps of knowledge.

Previous studies have found that patients in palliative care settings use various coping strategies to increase quality of life and decrease depression and hopelessness [Citation27]. In our subgroup analysis of patients in our study treated with palliative intent we found that they were, in general, satisfied with the overall communication at the oncological clinic.

The patients in this study were accrued from 16 hospitals in two countries and were included regardless of tumour stage and treatment plan, which contributes to the high external validity of our results. We also had very high response rates.

There may be a selection bias regarding the subgroup of patients with palliative intention of treatment, as patients with lower functioning level may not have been able to complete the extensive questionnaire. However, we lack information on WHO (World Health Organization) performance status of the patients.

The results of the study are of importance for the future development of communication with patients who receive information about the disease, the treatment and possible side-effects. In recent years the concept of shared decision-making has gained interest. It has mostly been emphasized in situations where neither research nor clinical experience indicates which treatment alternatives best serve the patient. We do not claim to study shared decision-making, but it is apparent that patients need to be properly informed to make an informed decision. However, satisfaction did not seem to correlate with the level of information.

In conclusion, our study implies that patients with rectal cancer generally experience the contact and communication with the healthcare personnel as very good. This is in contrast to the findings of less adequate information regarding alternative treatment options and potential side-effects of the planned treatment. However, if the patients are satisfied this might be the most important outcome of patient-centred communication regardless of exactly what the communication included.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Excel (14.2 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the work performed by the research nurses at the Scandinavian Surgical Outcomes Research Group, SSORG, and by all those involved in the recruitment of patients at participating hospitals: Sahlgrenska University Hospital/Östra, Göteborg; Skaraborg Hospital Skövde; NU Hospital Group, Trollhättan; Central Hospital of Karlstad; Södra Älvsborg Hospital, Borås; Karolinska University Hospital; Örebro University Hospital; Sunderbyn Hospital; Västmanland’s Hospital Västerås, Blekinge Hospital, Karlskrona; Mora Hospital; Helsingborg Hospital; Hvidovre Hospital; Slagelse Hospital; Herlev Hospital and Roskilde Hospital.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Glimelius B, Tiret E, Cervantes A, et al. Rectal cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:vi81–vi88.

- Shay LA, Lafata JE. Where is the evidence? A systematic review of shared decision making and patient outcomes. Med Decis Making. 2015;35:114–131.

- McCormack LA, Treiman K, Rupert D, et al. Measuring patient-centered communication in cancer care: a literature review and the development of a systematic approach. Soc Sci Med. 2011;72:1085–1095.

- Adams JR, Elwyn G, Legare F, et al. Communicating with physicians about medical decisions: a reluctance to disagree. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:1184–1186.

- Schuler M, Schildmann J, Trautmann F, et al. Cancer patients’ control preferences in decision making and associations with patient-reported outcomes: a prospective study in an outpatient cancer center. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25:2753–2760.

- Frosch DL, Kaplan RM. Shared decision making in clinical medicine: past research and future directions. Am J Prev Med. 1999;17:285–294.

- Kunneman M, Engelhardt EG, Ten Hove FL, et al. Deciding about (neo-)adjuvant rectal and breast cancer treatment: missed opportunities for shared decision making. Acta Oncol. 2016;55:134–139.

- Kunneman M, Marijnen CA, Baas-Thijssen MC, et al. Considering patient values and treatment preferences enhances patient involvement in rectal cancer treatment decision making. Radiother Oncol. 2015;117:338–342.

- Kunneman M, Pieterse AH, Stiggelbout AM, et al. Which benefits and harms of preoperative radiotherapy should be addressed? A Delphi consensus study among rectal cancer patients and radiation oncologists. Radiother Oncol. 2015;114:212–217.

- Angenete E, Asplund D, Andersson J, et al. Self reported experience of sexual function and quality after abdominoperineal excision in a prospective cohort. Int J Surg. 2014;12:1221–1227.

- Asplund D, Prytz M, Bock D, et al. Persistent perineal morbidity is common following abdominoperineal excision for rectal cancer. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2015;30:1563–1570.

- Emmertsen KJ, Laurberg S. Impact of bowel dysfunction on quality of life after sphincter-preserving resection for rectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2013;100:1377–1387.

- Feddern ML, Emmertsen KJ, Laurberg S. Life with a stoma after curative resection for rectal cancer: a population-based cross-sectional study. Colorectal Dis. 2015;17:1011–1017.

- Hutchinson AD, Hosking JR, Kichenadasse G, et al. Objective and subjective cognitive impairment following chemotherapy for cancer: a systematic review. Cancer Treat Rev. 2012;38:926–934.

- Steinmetz J, Rasmussen LS. Peri-operative cognitive dysfunction and protection. Anaesthesia. 2016;71(Suppl 1):58–63.

- Stefansson M, Nygren P. Oxaliplatin added to fluoropyrimidine for adjuvant treatment of colorectal cancer is associated with long-term impairment of peripheral nerve sensory function and quality of life. Acta Oncol. 2016;55:1227–1235.

- Steineck G, Helgesen F, Adolfsson J, et al. Quality of life after radical prostatectomy or watchful waiting. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:790–796.

- Brooks R. EuroQol: the current state of play. Health Policy. 1996;37:53–72.

- Antonovsky A. The structure and properties of the sense of coherence scale. Soc Sci Med. 1993;36:725–733.

- Asplund D, Heath J, Gonzalez E, et al. Self-reported quality of life and functional outcome in patients with rectal cancer–QoLiRECT. Dan Med J. 2014;61:A4841.

- Asplund D, Bisgaard T, Bock D, et al. Pretreatment quality of life in patients with rectal cancer is associated with intrusive thoughts and sense of coherence. Int J Colorectal Dis 2017;32:1639–1647.

- Kerr J, Engel J, Schlesinger-Raab A, et al. Doctor-patient communication: results of a four-year prospective study in rectal cancer patients. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:1038–1046.

- Snijders HS, Kunneman M, Bonsing BA, et al. Preoperative risk information and patient involvement in surgical treatment for rectal and sigmoid cancer. Colorectal Dis. 2014;16:O43–O49.

- Glimelius B, Cavalli-Bjorkman N. Does shared decision making exist in oncologic practice? Acta Oncol. 2016;55:125–128.

- Stacey D, Legare F, Lewis K, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;4:CD001431.

- Wu RC, Boushey RP, Scheer AS, et al. Evaluation of the rectal cancer patient decision aid: a before and after study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2016;59:165–172.

- van Laarhoven HW, Schilderman J, Bleijenberg G, et al. Coping, quality of life, depression, and hopelessness in cancer patients in a curative and palliative, end-of-life care setting. Cancer Nurs. 2011;34:302–314.