Abstract

Objectives: The purposes were to investigate the health status of elderly cancer patients by comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) and to compare the complications with respect to baseline CGA and to evaluate the need for geriatric interventions in an elderly cancer patients’ population.

Material: Patients aged ≥70 years with lung cancer (LC), cancer of the head and neck (HNC), colorectal cancer (CRC), or upper gastro-intestinal cancer (UGIC) are referred to the Department of Oncology for cancer treatment.

Methods: CGA was performed prior to cancer treatment and addressed the following domains: Activities of daily living (ADL), instrumental ADL (IADL), comorbidity, polypharmacy, nutrition, cognition, and depression. Complications, defined as dose reduction and discontinuation of treatment due to grade 3-4 toxicity, hospital admission, shift to palliative treatment, or death within 90 days, were identified from the medical files. Patients were classified as fit, vulnerable, or frail by CGA.

Principal results: Patients (N = 217) with a median age of 75 years (range: 70–93 yeas) were included: 13% were fit, 35% vulnerable, and 52% frail. CGA significantly predicted admittance to hospital in frail and vulnerable patients compared to fit patients: risk ratio (RR) 2.12 (95% CI: 1.01; 4.46). Vulnerable and frail patients had higher absolute risk of death within 90 days compared to fit patients: 7% and 23% versus 0%. HR for death within 90 days in frail patients as compared to vulnerable patients was 3.50 (95% CI: 1.34; 9.15). More frail patients (88%) needed geriatric interventions than the vulnerable (46%) and fit patients (32%).

Major conclusion: Few elderly cancer patients seem to be fit. CGA predicts admittance to hospital in a population of elderly patients with mixed cancer diseases. Frail and vulnerable patients have higher risk of death within 90 days as compared to fit patients.

The incidence and mortality of cancer rise with age [Citation1]. The aging of the Danish population during the next 25 years [Citation2] will lead to a rise in the number of older cancer patients. The health status of older patients is very heterogeneous. Some older patients have no comorbidity and are functionally independent; others struggle with comorbidities, polypharmacy, functional dependence, or problems with cognition or mood. The health status of older patients can be characterized by a comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA). The CGA is “a simultaneous, multi-level assessment of various domains by a multidisciplinary team to ensure that problems are identified, quantified and managed appropriately” [Citation3]. Accordingly, CGA comprises information on comorbidity, polypharmacy, physical, psychological and cognitive functions [Citation3], nutrition, and social status and support. Several studies have discussed the influence of such factors on prognosis and survival [Citation4–11], response to treatment [Citation7,Citation8,Citation12,Citation13], and increased adverse effects from the cancer treatment including deviations from the initially planned treatment intensity [Citation14–16].

Frailty

A frail person has increased vulnerability, and a heightened risk of adverse effects caused by reduced organ reserve capacity. Frailty is a potentially reversible state. It is known that older cancer patients may become frail during cancer treatment [Citation13]. In geriatric medicine, frailty is often determined by the presence of one or more clinical criteria as first described by Winograd [Citation17] and later refined by Balducci [Citation18]. Based on these criteria, Kristjansson et al. defined frailty on the basis of CGA and demonstrated that CGA predicted complications in older patients after elective surgery for colorectal cancer (CRC) [Citation19]. Later, this frailty assessment was shown to predict 1-year and 5-year mortality in the same group of patients [Citation20].

Comprehensive geriatric assessment

CGA of an aged cancer patient can determine whether the patient is fit or frail or in a condition between these two states. Fit patients have no or minimal comorbidity and no functional dependency. Frail patients are dependent in one or more activities of daily living (ADL), three or more severe comorbid conditions, and one or more geriatric syndromes [Citation18].

The International Society of Geriatric Oncology, SIOG, recommends that geriatric assessment is offered to all old cancer patients [Citation21]. In Denmark, systematic CGA is not routinely performed in older cancer patients. CGA can be an important help to provide tailored treatment in older cancer patients [Citation22]. Most previous studies have focused on CGA performed on patients with a single cancer-type or receiving specific treatments [Citation12,Citation23–28]. Such studies may not reflect the everyday population of cancer patients referred to oncology clinics.

Aim

First and most importantly, we aimed at describing the frailty status of older cancer patients in a Danish population referred to the oncology outpatient clinic for treatment. Secondly, we aimed at describing the risk of complications with respect to the baseline CGA. Thirdly, we wished to determine to which degree these patients require geriatric interventions.

Patients and methods

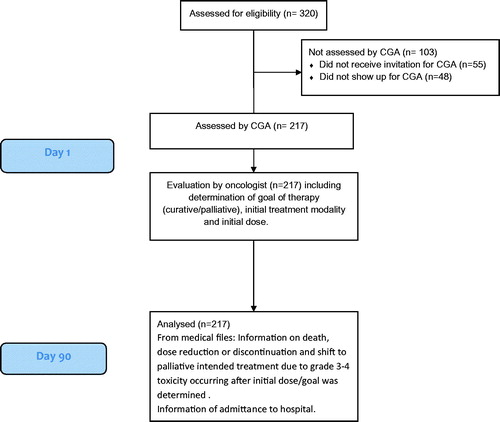

This study is a cohort study with follow-up after 3 months. displays the details of the identification and follow-up of patients.

Patients

Patients were offered CGA if they were:

diagnosed with lung cancer (LC), cancer of the head and neck (HNC), colo-rectal (CRC) or upper gastro-intestinal cancer (UGIC)

living in the Central Denmark Region

aged 70 years or more

referred to the Department of Oncology for evaluation for cancer treatment

Patients would qualify for participation regardless the cancer disease being newly diagnosed or a relapse of previously treated cancer and regardless if the patients were allocated to specific cancer treatment or not.

Patients suffering from any stage of cancer were included, and both local, loco-regional cancer disease and advanced disease. Patients whose, as initially, planned treatment was surgery were not included prior to surgery. Surgically treated patients, who were postoperatively referred to the oncology department for adjuvant treatment, were qualified for participation.

The Department of Oncology was responsible for planning time and date for CGA. Patients were informed of their appointment time and that they would be offered CGA at the Oncology Outpatient Clinic at Aarhus University Hospital by letter or email. CGA was preferably planned on the day of the first appointment with the oncologist.

Initial oncological treatment information

Information on the initially planned oncological treatment plan was registered from the electronic medical file. We collected information on initial oncological treatment goal (curative, adjuvant or palliative, no treatment), initial dose (standard or reduced), and initial treatment strategy (radiation and/or chemotherapy).

CGA

CGA was performed by a multidisciplinary team consisting of a trained geriatric nurse and a geriatrician prior to initiation of the cancer treatment.

Superiority of one tool for CGA over another has not been shown [Citation29]. In this study, we have chosen well-validated tools often used in geriatric research:

Functional status was assessed by three measures: ADL, instrumental ADL (IADL), and Timed Up and Go (TUG).

ADL was assessed by BARTHEL 100 [Citation30,Citation31]. It comprises 10 domains of daily living. Each domain is scored and may range from 0 (totally dependent) to 5–15 (independent). The total sum-score ranges from 0 to 100. A score of 90 and above indicates independence.

Functional Activities Questionnaire (FAQ) IADL [Citation32,Citation33] assesses 10 domains of daily life. The ability to handle financial matters, transportation, housekeeping, laundry, preparation of food, shopping and administration of own medications etc., is assessed. The scores range from 0 to 3 in all domains. A higher score indicates higher degree of dependence. Scores 0–1 in any domain (normal function/manages with problems) indicate independence. Scores 2–3 in any domain (needs help/dependent on help) indicate dependency. Highest sum-score is 30 indicating total dependence.

Comorbidity is the co-occurrence of other diseases in a patient with an index disease. In this context, the index disease is the cancer diagnosis. Information on comorbidity was obtained from review of hospital records supplemented with information from the patient interview using the Cumulative Indexed Rating Scale-Geriatrics (CIRS-G) [Citation34], and this was scored according to the modified guidelines 2008 [Citation35]. The CIRS-G assesses 14 organ systems, scoring comorbidity in each organ system by a five-point scale ranging from grade 0 (no problem) to grade 4 (extremely severe/immediate treatment required/end organ damage). CIRS-G comprises both information on diagnoses and severity of diagnoses. In addition, CIRS-G also comprises information on lifestyle factors such as smoking and abuse of alcohol, use of, for example, anxiolytics and previous conditions such as earlier cancer diseases or kidney stones.

Mental status was assessed by Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) 15-item scale [Citation36] and Mini-Mental State Examination, (MMSE) [Citation37]. Both were performed as interviews.

GDS assesses mood and contains 15 questions to be answered yes or no, giving a total score of 0–15. Higher scores indicate more depressive symptoms. 0–4 are normal scores. A score ≥5 indicates depression. In a Danish population of older community-dwelling persons receiving home care who had MMSE scores from 16 to 30, a cutoff point of 5 on the GDS indicated depression with a sensitivity of 83% and specificity of 84% [Citation38].

MMSE is a screening instrument for cognitive impairment. It includes 20 items testing a variety of cognitive functions including orientation, abstraction, and visuo-spatial ability. The score ranges from 0 to 30. A score <24 is indicative of cognitive problems. A score of >28 indicates no cognitive problems.

Nutritional status was assessed by the Mini-Nutritional Assessment (MNA) [Citation39] screening instrument indicative of the nutritional status. Lower scores indicate impaired nutritional status. A score ≥24 indicates normal nutritional status and a score <17 malnutrition.

Classification of patients by CGA

Based on the results of CGA, patients were classified into three groups according to their robustness: fit, vulnerable, and frail. Fulfilling of all following criteria defined fit patients: little or no comorbidity, independency in both ADL and IADL, absence of cognitive problems and depressive symptoms, a normal nutritional status, and less than 5 daily medications. Frail patients were defined by any of following: dependence in ADL, three or more severe comorbidities or any extremely severe comorbidity, cognitive problems, depressive symptoms, malnutrition or more than seven daily medications. Patients neither fit nor frail were classified as vulnerable (for further information, see supplementary material). The group of patients neither fit nor frail is inconsistently labeled in the literature: In some studies, the group is named ‘intermediate’ [Citation19,Citation28,Citation40] or ‘pre-frail’ [Citation41] and in other studies the group ‘vulnerable’ [Citation23,Citation42,Citation43]. In the present study, we use ‘vulnerable’ to describe this CGA group. We chose to use the same CGA-based frailty classification as previously published by Kristjansson [Citation12]. This classification is based on the Balducci criteria [Citation18]. The result of CGA was included in the electronic medical file, which was available to the oncologist. The result of CGA was sent to the patients’ general practitioner. Information on patients’ identified need for intervention was registered in four categories: Need for change in medication, nutritional optimization, physical exercise, and optimization of the social situation.

Supplementary information collected on each patient

Registration of housing type was noted as follows: living independently, sheltered housing, or nursing home. Living alone or living with others was also registered.

A numeric rating scale was used to assess pain, ranging from 0 to 10. A higher score indicates higher pain intensity.

Information on the patients’ mobility and the use of walkers indoor and/or outdoor was registered. Also, the patients’ need of either personal or practical home care services.

Follow-up

Information on complications during 90 days’ follow-up was collected from the electronic medical file by the geriatric nurse. We registered five types of complications: (1) dose reduction due to grade 3-4 toxicity (according to Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) Version 4) [Citation44] or (2) discontinuation due to grade 3-4 toxicity, if any initial treatment was planned, (3) hospital admission, (4) shift to palliatively intended treatment if initial curative treatment was planned, and (5) time to death. Admissions to day hospital solely for the purpose of receiving chemotherapy were not registered as admissions to hospital. Date of death was automatically registered in the electronic medical file regardless of death occurring in the hospital or in the community. For further details, see .

Ethical approval

The patients received standard treatment for their cancer disease. CGA was an add-on offered to all cancer patients. Ethical approval was not considered necessary by the local ethic committee (file number 1-10-72-168-17). The study was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency (Approval number 1-16-02-3-14) and registered at Clinical Trials.gov: NCT02072733.

Statistical analysis

CGA was used to classify the patients as fit, vulnerable, or frail. To compare the characteristics of these three groups of patients, Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used for the continuous non-parametric variables, and Chi-squared test or Fisher's Exact test for the categorical variables.

The initial CGA classification was compared according to each type of the complications: dose reduction, discontinuation, hospital admission, shift to palliative treatment, and death. In a binary regression model, we analyzed the occurrence of dose reduction and discontinuation of treatment within 90 days after CGA in the frail and vulnerable patients, respectively, compared with the fit patients as a reference. The model was adjusted for gender, age, cancer disease, and metastatic status when analyzing dose reduction and admittance to hospital but only primary tumor site when analyzing discontinuation due to few events. As there were no deaths within 90 days in the fit group, an analysis with fit patients as references could not be performed, instead we performed a Cox proportional hazard regression analysis of time to death and compared vulnerable patients to frail patients adjusting for primary tumor site.

Any p value ≤.05 was considered statistically significant. Stata software version 15.0 was used for all the statistical analyses.

Results

Patient identification

In total, 320 relevant patients were consecutively identified between January 8, 2015 and December 31, 2015. Of these, 265 (83%) had received a letter or email that they would be offered CGA, when scheduled for appointment at the oncology outpatient clinic. Of the invited patients, 217 (82%) showed up for CGA.

The patients not receiving CGA had similar age, cancer diagnoses, and gender as the patients receiving CGA. Patients not appearing for CGA lived at the same distance from hospital.

Frailty status of older cancer patients

Baseline characteristics of patients receiving CGA are shown in . Mean duration of CGA was 51 (95% CI: 49; 53) min and additional 5–10 min for calculating the CIRS-G score. Median age was 75 years (IQR: 72–80, range: 70–88). Gender was equally distributed in the CGA groups. Most patients had the LC diagnose. Of the 217 patients undergoing CGA, only 13% were fit and more than half of patients were frail. There was no difference in age in the CGA groups. Comparison of baseline characteristics’ distribution among the CGA groups is shown in .

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of patients receiving CGA in the total population and in relation to the CGA classification ‘fit’, ‘vulnerable’, and ‘frail’.

There was a significant difference in frailty status in the four cancer groups (p < .01). LC- and UGIC patients were more often frail and rarely fit; CRC patients were most often fit. The number of patients with HNC was relatively small, and the data should be interpreted with caution.

The most prevalent comorbidities were vascular/hematopoietic (including anemia), hypertension, and endocrine-metabolic diseases.

One or more grade-3 comorbidities were observed in 57% of the patients, and 9% of patients had one or more grade 4-comorbidities. A significant difference in the initial oncological treatment strategy was observed in the three CGA groups (). Treatment with curative intent was more often offered to fit patients than to non-fit, who were more often given palliative treatment. Fit patients were more likely to have adjuvant treatment. More often, frail patients were not offered specific oncological treatment. In general, most patients appeared independent in ADL and with small though statistical significant difference in functional status when measured by TUG (median: 11 s, IQR: 9–13 s).

Table 2. Initially planned cancer treatment and interventions provided following CGA in the total population and in relation to the CGA classification ‘fit’, ‘vulnerable’, and ‘frail’.

Complications

During a 3-month period, 62% (n = 135) of the patients experienced one or more complication. There was a significant difference in the occurrence of complications in the CGA groups (p = .03), frail patients having more complications than vulnerable and fit. Some patients had more than one complication.

Only eight patients changed from treatment with curative to palliative intend. There was no difference between the CGA groups regarding shift to palliative treatment in the subgroup of patients initially assigned to curatively intended treatment (p = .98). There was no difference in complications related to age (p = .43). In , complications in the CGA groups are compared.

Table 3. Comparison of complications in relation to initial CGA according to fit, vulnerable, and frail cancer patients.

No difference in the occurrence of dose-reduction or discontinuation of treatment was found between the CGA groups. Vulnerable patients had a significantly higher relative risk (RR) of being admitted to hospital for any reason within 90 days (RR: 2.12 (95% CI: 1.01; 4.46), p = .047). Frail patients had a tendency toward having more admittances to hospital compared to fit patients (RR: 2.01 (95% CI: 0.96; 4.19, p = .065), but the data failed to reach statistical significance. Primary tumor site did not add significantly to these regression models, whereas younger age contributed little, but statistically significant in the regression model of admittance to hospital. Frail patients had a higher absolute risk of death within 90 days than fit patients (23% vs. 0%). When comparing death within 90 days of CGA among vulnerable and frail patients, we found an increased risk of death in the frail group when compared to the vulnerable group, HR: 3.50 (95% CI: 1.34; 9.15) p = .011. Primary tumor site did not contribute significantly to this model.

Need of geriatric interventions

Per definition, frail patients need significantly more geriatric interventions in the defined categories than vulnerable and fit patients ().

In 162 patients (75%), a need of geriatric intervention was identified by CGA. Of those, 159 accepted the proposed interventions. Of those who accepted the interventions, 84% were proposed medication changes, 65% nutritional optimization, and 23% physical exercise either as home exercise or by referral to physiotherapy. For 21%, optimization of the social situation was arranged, most often as additional home care service. The only single intervention to reach statistical significance was nutritional intervention (p = .025). There was a tendency for frail patients to be more in need of medical interventions, but data did not reach statistical significance (p = .08).

Discussion

Frailty status of older cancer patients

Our study established that most of the older cancer patients included were vulnerable or frail. A comparable distribution of frailty status was found in a population of older CRC patients using a similar method for classifying frailty [Citation19]. In that population, there were very few fit patients (12%). Most patients were intermediate (45%) or frail (43%) [Citation12]. Furthermore, frailty predicted perioperative complications and inferior survival [Citation19,Citation20]. Other studies performing CGA in groups of patients with a variety of cancer diagnoses had another distribution of frailty with either a higher rate of fit patients [Citation42,Citation45] or a lower number of frail patients [Citation46]. However, those studies included patients with a wider variety of cancer diagnoses as well as younger patients than in our study. In general, the frailty status of older cancer patients depends on the age and the cancer diagnoses of the study population. We have included cancer types often seen in older patients and cancer types often connected to comorbidity. Our classification of frailty may be questioned as the method has previously been used in older cancer patients undergoing operation for CRC. However, it was adapted from the Balducci criteria except for age and falls. With little modifications, this frailty classification has been used in other studies of mixed cancer populations [Citation43] where frailty predicted less survival. Age is incorporated in the original Balducci criteria and in some otherwise comparable frailty classifications [Citation47], but others have not included age as a frailty criterion [Citation48]. As comorbidity, dependence and cognitive decline are more prevalent in older patients, the age-dependent frailty may be captured by other criteria than strict age. In our study, we found no difference in age in the CGA groups. This contrasts with the latent classes defined by Ferrat [Citation49], that otherwise correspond well to the CGA classes defined by Balducci. In that study, age >80 years was more predominant in the ‘globally impaired’ class. But that population consisted of both in-patients and out-patients and could not be compared directly to the patients in our study. Falls is part of the Balducci criteria as well. We did not specifically register falls, but basic mobility is part of the Barthel-100 assessment [Citation30] which is incorporated in the frailty classification.

Complications

In the heterogeneous population of the present study, frailty status differed as expected between primary tumor sites and planned treatments. A clinical evaluation of frailty or a proxy of frailty, for example, performance status, comorbidities etc., has probably been considered by the oncologist when deciding treatment intensity. Therefore, frailty did not contribute with as much extra information for the prediction of complications, as could have been expected.

It is possible that the process of performing CGA and handling the identified problems may have affected the rate of complications. We considered it to be unethical to identify problems in health status and not trying to remedy them. However, it has previously been established that CGA is only efficient when a geriatric follow-up of identified problems is applied [Citation50]. The present study did not include follow-up on identified problems. Data on presence of metastases were missing in 10 patients. This may have influenced the comparison of complications between the CGA groups. We found a higher risk of admittance to hospital among vulnerable patients as compared to fit patients with a small but statistically significant contribution of younger age in the regression model; this finding was not statistically significant in the frail group. The data cannot clarify whether this finding is caused by younger patients more often accept admittance or if younger patients are more often considered to benefit from admittance to hospital. We did not register length of stay among the participants. As no fit patients died during the follow-up period, a HR of death within 90 days could not be compared among all CGA groups. Therefore, we present the absolute risk of death, which is markedly higher among frail patients than both vulnerable and fit patients. We found a significantly higher HR of death among frail patients as compared to vulnerable patients. This supports previous findings that frailty predicts death [Citation20,Citation43]. There was a heterogeneous distribution of tumor sites among the CGA groups. This may have contributed to the findings mentioned above, but it did not add significantly to the regression model.

Need of geriatric intervention

Per definition, more frail than fit patients required geriatric intervention. The frequency of patients requiring geriatric intervention identified by CGA is dependent on the population examined. Chapman et al. found that 62% of an older cancer population were malnourished or in risk of malnutrition and additionally made recommendation on medication changes in more than 75% of patients and some kind of improvement of social situation in over 50% [Citation42]. Kenis et al. found that an average of two geriatric recommendations were given to each older cancer patient [Citation51] and that unknown geriatric problems were found in more than half of patients leading to geriatric intervention in approximately 25% of patients [Citation52]. The latter study had 29% of fit patients in contrast to the present study where only 13% were fit. Additionally, that study left it to the discretion of the oncologist whether to initiate the interventions proposed by the CGA. In our study, the multidisciplinary team was able to initiate interventions immediately following the geriatric assessment without any delay. But the design did not include any follow-up on the proposed interventions leaving an uncertainty if our recommendations were complied with.

Strength and limitations

Our study has several limitations. First, the population is heterogeneous and received heterogeneous treatment regimes. This limits the predictive value for the single cancer patient. Furthermore, as the primary aim of the study was to describe the general health status of patients referred to the oncology clinic, we included patients, that did not receive any treatment at all, leaving the uncertainty if the complications (e.g., hospital admittance) had any connection to the cancer disease or cancer treatment. A setup with a time-consuming full-scale CGA to all patients may not be feasible in everyday working practice. We chose, however, this approach due to the primary aim of the study. Some sort of screening process prior to CGA would probably be advisable. This question is however beyond the scope of this study.

One of the strengths of our study is the consecutively included patients. Patients were identified by persons not involved in patient treatment or geriatric assessment. CGA was performed by well-validated tools often used in geriatric research and with clearly described cutoff scores, thereby increasing reproducibility.

We managed to obtain a high degree of participation. Furthermore, the patients included in this study represent a wide age range. In addition, information was collected prospectively. This minimizes the risk of recall bias in the interviews of CGA. The information regarding physical abilities obtained in the interviews might be overestimated as patients may seek to perform as well as possible to be considered eligible for treatment. The risk of such possible overestimation of physical ability is reduced by the presence of relatives who most often accompany patients and who may be able to verify information given. Furthermore, all patients were evaluated by TUG. We found a statistically significant but small difference in TUG among the CGA groups. In general, TUG among patients in our study was good as compared to the applied threshold for predicting complications in other studies of TUG among older cancer patients [Citation53]. As TUG is an objective measure, this support the information obtained by the interviews.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we found that most older cancer Danish patients referred to an oncology outpatient clinic seem to be vulnerable or frail. Frailty status may predict admittance to hospital and death within 3 months. A large proportion of older cancer patients require geriatric intervention identified by CGA. Frail and vulnerable patients more often seem to need interventions compared to fit patients. With the existing information on tumor site, comorbidities, and metastatic status, it seems that oncologists are able to select patients for suitable treatment, but CGA adds information to the clinical judgment. CGA contributes with information in a large proportion of patients.

Future studies

This study raises several questions to be explored in future studies. Most importantly, is it possible to reduce complications in older vulnerable and frail cancer patients by applying geriatric follow-up on problems identified by CGA? In the literature, there is a lack of knowledge based on randomized studies regarding this subject. CGA can be used to identify the patients at risk of complications. This may increase the chance for older cancer patients to complete intensive cancer treatment with fewer complications and decrease the risk of allocation of frail patients to too toxic treatment. This latter issue still needs to be addressed in randomized studies. We are currently including patients in a relevant study (Clinical Trials.gov: NCT02837679).

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (22.1 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Engholm G, Ferlay J, Christensen N, et al. NORDCAN: Cancer Incidence, Mortality, Prevalence and Survival in the Nordic Countries, Version 7.3 (08.07.2016). Association of the Nordic Cancer Registries. Danish Cancer Society. 2016; [cited 2018 May 25] Available at: http://www.ancr.nu.

- Danmarks S. http://www.danmarksstatistik.dk/da/Statistik/emner/befolkning-og-befolkningsfremskrivning/befolkningsfremskrivning?tab=nog. 2015.

- Ellis G, Whitehead Martin A, O'Neill D, et al. Comprehensive geriatric assessment for older adults admitted to hospital. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;343:d6553.

- Honecker FU, Wedding U, Rettig K, et al. Use of the comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) in elderly patients (pts) with solid tumors to predict mortality. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:9549.

- Soubeyran P, Fonck M, Blanc-Bisson C, et al. Predictors of early death risk in older patients treated with first-line chemotherapy for cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1829–1834.

- Iversen LH, Norgaard M, Jacobsen J, et al. The impact of comorbidity on survival of Danish colorectal cancer patients from 1995 to 2006-a population-based cohort study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52:71–78.

- Dent E, Chapman I, Howell S, et al. Frailty and functional decline indices predict poor outcomes in hospitalised older people. Age Ageing. 2014;43:477–484.

- Land LH, Dalton SO, Jensen MB, et al. Impact of comorbidity on mortality: a cohort study of 62,591 Danish women diagnosed with early breast cancer, 1990-2008. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;131:1013–1020.

- Marenco D, Marinello R, Berruti A, et al. Multidimensional geriatric assessment in treatment decision in elderly cancer patients: 6-year experience in an outpatient geriatric oncology service. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2008;68:157–164.

- Ferrat E, Paillaud E, Laurent M, et al. Predictors of 1-year mortality in a prospective cohort of elderly patients with cancer. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2015;70:1148–1155.

- Hamaker ME, Buurman BM, van Munster BC, et al. The value of a comprehensive geriatric assessment for patient care in acutely hospitalized older patients with cancer. Oncologist 2011;16:1403–1412.

- Kristjansson SR, Ronning B, Hurria A, et al. A comparison of two pre-operative frailty measures in older surgical cancer patients. J Geriatr Oncol. 2012;3:1–7.

- Pottel L, Lycke M, Boterberg T, et al. Serial comprehensive geriatric assessment in elderly head and neck cancer patients undergoing curative radiotherapy identifies evolution of multidimensional health problems and is indicative of quality of life. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2014;23:401–412.

- Wanders R, Steevens J, Botterweck A, et al. Treatment with curative intent of stage III non-small cell lung cancer patients of 75 years: a prospective population-based study. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47:2691–2697.

- Caillet P, Canoui-Poitrine F, Vouriot J, et al. Comprehensive geriatric assessment in the decision-making process in elderly patients with cancer: ELCAPA study. JCO. 2011;29:3636–3642.

- Kim J, Hurria A. Determining chemotherapy tolerance in older patients with cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2013;11:1494–1502.

- Winograd CH, Gerety MB, Chung M, et al. Screening for frailty: criteria and predictors of outcomes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1991;39:778–784.

- Balducci L, Extermann M. Management of cancer in the older person: a practical approach. Oncologist 2000;5:224–237.

- Kristjansson SR, Nesbakken A, Jordhoy MS, et al. Comprehensive geriatric assessment can predict complications in elderly patients after elective surgery for colorectal cancer: a prospective observational cohort study. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2010;76:208–217.

- Ommundsen N, Wyller TB, Nesbakken A, et al. Frailty is an independent predictor of survival in older patients with colorectal cancer. Oncologist. 2014;19:1268–1275.

- Extermann M, Aapro M, Bernabei R, et al. Use of comprehensive geriatric assessment in older cancer patients: recommendations from the task force on CGA of the International Society of Geriatric Oncology (SIOG). Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2005;55:241–252.

- Schulkes KJG, Souwer ETD, Hamaker ME, et al. The effect of a geriatric assessment on treatment decisions for patients with lung cancer. Lung 2017;03:1–7.

- Girones R, Torregrosa D, Maestu I, et al. Comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) of elderly lung cancer patients: a single-center experience. J Geriatr Oncol. 2012;3:98–103.

- Olivieri A, Gini G, Bocci C, et al. Tailored therapy in an unselected population of 91 elderly patients with DLBCL prospectively evaluated using a simplified CGA. Oncologist 2012;17:663–672.

- Merli F, Luminari S, Rossi G, et al. Outcome of frail elderly patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma prospectively identified by Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment: results from a study of the Fondazione Italiana Linfomi. Leuk Lymphoma. 2014;55:38–43.

- Hamaker ME, Seynaeve C, Wymenga ANM, et al. Baseline comprehensive geriatric assessment is associated with toxicity and survival in elderly metastatic breast cancer patients receiving single-agent chemotherapy: Results from the OMEGA study of the Dutch Breast Cancer Trialists' Group. Breast 2014;23:81–87.

- Aaldriks AA, Giltay EJ, le Cessie S, et al. Prognostic value of geriatric assessment in older patients with advanced breast cancer receiving chemotherapy. Breast 2013;22:753–760.

- Marchesi F, Cenfra N, Altomare L, et al. A retrospective study on 73 elderly patients (>/=75years) with aggressive B-cell non Hodgkin lymphoma: clinical significance of treatment intensity and comprehensive geriatric assessment. J Geriatr Oncol. 2013;4:242–248.

- Wildiers H, Heeren P, Puts M, et al. International society of geriatric oncology consensus on geriatric assessment in older patients with cancer. JCO. 2014;32:2595–2603.

- MAHONEY FI, BARTHEL DW. Functional evaluation: the Barthel Index. Md State Med J. 1965;14:61–65.

- Rouge-Bugat ME, Gerard S, Balardy L, et al. Impact of an oncogeriatric consulting team on therapeutic decision-making. J Nutr Health Aging. 2013;17:473–478.

- Pfeffer RI, Kurosaki TT, Harrah CH, et al. Measurement of functional activities in older adults in the community. J Gerontol. 1982;37:323–329.

- Morris JC, Weintraub S, Chui HC, et al. The Uniform Data Set (UDS): clinical and cognitive variables and descriptive data from Alzheimer Disease Centers. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2006;20:210–216.

- Parmelee PA, Thuras PD, Katz IR, et al. Validation of the cumulative illness rating scale in a geriatric residential population. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1995;43:130–137.

- Salvi F, Miller MD, Grilli A, et al. A manual of guidelines to score the modified Cumulative Illness Rating Scale and its validation in acute hospitalized elderly patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:1926–1931.

- Sheikh JI, Yesavage JA. Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS): recent evidence and development of a Shorter Version. Clin Gerontol. 1986;5:165–173.

- Folstein MF, Robins LN, Helzer JE. The Mini-Mental State Examination. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1983;40:812

- Djernes JK, Kvist E, Olesen F, et al. Validation of a Danish translation of Geriatric Depression Scale-15 as a screening tool for depression among frail elderly living at home. Ugeskr Laeger. 2004;166:905–909.

- Guigoz Y, Vellas B, Garry PJ. Assessing the nutritional status of the elderly: the Mini Nutritional Assessment as part of the geriatric evaluation. Nutr Rev. 1996;54:S59–S65.

- Massa E, Madeddu C, Lusso MR, et al. Evaluation of the effectiveness of treatment with erythropoietin on anemia, cognitive functioning and functions studied by comprehensive geriatric assessment in elderly cancer patients with anemia related to cancer chemotherapy. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2006;57:165–175.

- Farcet A, de Decker L, Pauly V, et al. Frailty markers and treatment decisions in patients seen in oncogeriatric clinics: results from the ASRO pilot study. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0149732.

- Chapman AE, Swartz K, Schoppe J, et al. Development of a comprehensive multidisciplinary geriatric oncology center, the Thomas Jefferson university experience. J Geriatr Oncol. 2014;5:164–170.

- Basso U, Tonti S, Bassi C, et al. Management of frail and not-frail elderly cancer patients in a hospital-based geriatric oncology program. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2008;66:163–170.

- U.S.DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) Version 4.0 2009; [cited 2018 Feb 23] Available at: https://www.eortc.be/services/doc/ctc/CTCAE_4.03_2010-06-14_QuickReference_5x7.pdf.

- Massa E, Madeddu C, Astara G, et al. An attempt to correlate a "Multidimensional Geriatric Assessment" (MGA), treatment assignment and clinical outcome in elderly cancer patients: results of a phase II open study. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2008;66:75–83.

- Hentschel L, Rentsch A, Lenz F, et al. A questionnaire study to assess the value of the vulnerable elders survey, G8, and predictors of toxicity as screening tools for frailty and toxicity in geriatric cancer patients. Oncol Res Treat. 2016;39:210–216.

- Tucci A, Ferrari S, Bottelli C, et al. A comprehensive geriatric assessment is more effective than clinical judgment to identify elderly diffuse large cell lymphoma patients who benefit from aggressive therapy. Cancer 2009;115:4547–4553.

- Droz JP, Aapro M, Balducci L, et al. Management of prostate cancer in older patients: updated recommendations of a working group of the International Society of Geriatric Oncology. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:e404–e414.

- Ferrat E, Audureau E, Paillaud E, et al. Four distinct health profiles in older patients with cancer: latent class analysis of the prospective ELCAPA cohort. Gerona. 2016;71:1653–1660.

- Stuck AE, Siu AL, Wieland GD, et al. Comprehensive geriatric assessment: a meta-analysis of controlled trials. Lancet 1993;342:1032–1938.

- Kenis C, Heeren P, Decoster L, et al. A Belgian survey on geriatric assessment in oncology focusing on large-scale implementation and related barriers and facilitators. J Nutr Health Aging. 2016;20:60–70.

- Kenis C, Bron D, Libert Y, et al. Relevance of a systematic geriatric screening and assessment in older patients with cancer: results of a prospective multicentric study. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:1306–1312.

- Verweij NM, Schiphorst AH, Pronk A, et al. Physical performance measures for predicting outcome in cancer patients: a systematic review. Acta Oncol. 2016;55:1386–1391.