Introduction

Although the treatment of breast cancer has achieved numerous improvements, long-term survival for metastatic disease remains poor. The lines of chemotherapy are limited and there is no single accepted standard of care once initial chemotherapy has failed [Citation1]. New treatments with survival benefits are needed.

In 2011, results from the EMBRACE study [Citation2] showed a survival benefit in favour of eribulin compared to physicians choice in the treatment of metastatic breast cancer. The overall survival (OS) benefit was 2.5 months. Eribulin, which is a non-taxane inhibitor of the microtubule dynamics, was approved by FDA and EMA in 2010 and 2011, respectively.

This retrospective study describes the observed effect and side effects of eribulin in patients treated in everyday practice. Our aim is to present the observed PFS and OS and describe the side effects. We have previously presented data from 40 patients on side effects [Citation3], but now the data is complete and response data is included.

Patients and methods

We identified all patients who began treatment with eribulin from 2011 to 2015 in the Departments of Oncology at Aarhus University Hospital, Herning Hospital and Aalborg University Hospital. All patients had metastatic breast cancer and most patients had received several different chemotherapy regimens beforehand.

Eribulin was administered intravenously on days 1 and 8 of a 21-day cycle. In HER2 positive patients, eribulin was given in combination with trastuzumab every three weeks. Treatment continued until progression or unacceptable side effects. Dose reduction was performed to manage toxicity and some patients had their dose reduced upfront due to previously experienced side effects to chemotherapy or frailty [Citation3].

A systematic review of electronic patient records, laboratory findings, pathology and radiological results was performed. Also, the reported side effects, treatment delays, dose reductions and response to treatment were registered. The side effects are partly self-reported and partly retrospectively collected from the patient records. The side effects have been graded according to Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 4.

Results

A total of 130 women treated with eribulin for metastatic breast cancer were identified. The patient and tumour characteristics are shown in .

Table 1. Baseline characteristics (N = 130).

A high number of patients had liver metastasis and multiple organ involvement. The vast majority of patients presented in PS 0–2, but a few patients received treatment despite being described as PS 3. Most of the patients with poor performance status did not tolerate the treatment.

The women were treated with a mean of three prior regimens of chemotherapy for advanced disease (). Prior therapy included both anthracyclines and taxanes in most cases. About 25 of 32 patients with HER2 overexpression have received treatment with concomitant trastuzumab.

A median overall OS of 8.1 months (95% CI: 6.7–9.6) was found. Our observed median overall PFS was 3.0 months (95% CI: 1.87–4.0).

Subgroup analysis by estrogen receptor (ER) and HER2 status revealed a statistical significant difference in OS and PFS in the patients with triple negative disease (p = 0.01). Triple negative disease having the worse outcome. Patients with ER positive tumours have a significantly longer PFS but no difference regarding OS was found.

The number of affected organs was important for survival; with a significant difference in OS according to the number of organs involved, but without significant difference in PFS.

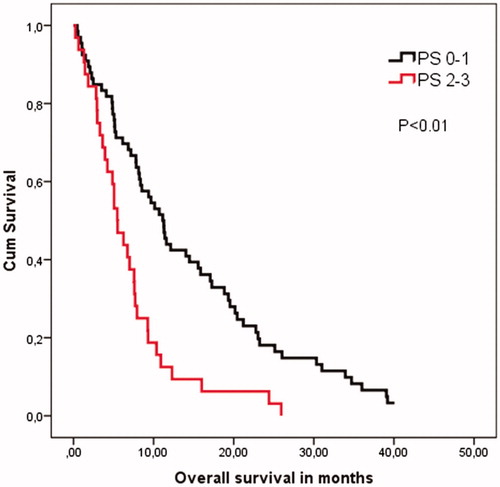

There was a significant difference in OS depending on PS groups (PS 0–1 vs. PS 2–3) of 11 months vs. 5 months (p < 0.01), but this was not the case with PFS ().

Figure 1. Overall survival according to the patients’ performance status at the beginning of eribulin treatment. Survival is significantly shorter among patients with PS 2–3. Kaplan–Meier survival analysis and log rank cow regression analysis is performed.

The objective response rate was 15% (ORR = CR + PR) and the clinical benefit rate was 25% (CBR = ORR + SD).

The most frequent side effects were fatigue, neuropathies, muscle- and joint pain, nausea and loss of appetite (). Neutropenia was the most frequent haematological side effect with 17% of patients experiencing neutropenia grade 3 or worse. Most hospitalisations were due to febrile neutropenia, infections or progressive disease causing pleural effusion, development of medullary compression or CNS metastasises. Unfortunately, we observed two treatment related deaths. One patient died in a combined state of neutropenia and sepsis followed by multi-organ failure. The other patient was not neutropenic but died from a combination of cardiac failure and infection. She presented in poor PS even before treatment which might have contributed.

Table 2. Adverse events.

Discussion

Differences between the patients included in clinical trials and those treated on a daily basis in the clinic are well known. Trials tend to be done on highly selected patients who are not always representative of the general patient population. They tend to be younger with fewer comorbidities and have a better PS [Citation4]. When the trials have been published, and the drugs approved, we use them on a wider patient population. It is therefore of importance to investigate the efficacy and safety in our everyday patients.

Our median OS was 8.1 months and median PFS was 3.0 months. Compared to EMBRACE [Citation2] this is a poor survival. While the baseline characteristics of our patients are comparable to those of EMBRACE [Citation2] regarding age, receptor status and dissemination of the disease, our patients were more often in poor performance status. This might explain our shorter OS, as we see a significant better outcome in the subgroup of patients with PS 0–1.

Our OS is however comparable to that shown in previous studies on real-life patients [Citation5, Citation6]. Our PFS is comparable to that seen in EMBRACE and other studies [Citation7–9] and the same is seen regarding the clinical benefit rate.

In conclusion we can confirm that eribulin is relatively well tolerated in our routine setting. Side effects being mainly fatigue, neuropathies, muscle and joint pain, neutropenia and nausea/loss of appetite. About 25% of the treated patients obtained a clinical benefit from the treatment.

As with any chemotherapy it is of utmost importance to carefully consider the performance status of the patient before treatment in initiated. Based on our data eribulin should be used with caution in patients in PS 2 or higher. Patients who are too fragile have no survival gain and are in risk of dying due to side effects.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Cardoso F, Costa A, Senkus E, et al. 3rd ESO–ESMO international consensus guidelines for Advanced Breast Cancer (ABC 3). The Breast. 2017;31:244–259.

- Cortes J, O'Shaughnessy J, Loesch D, et al. Eribulin monotherapy versus treatment of physician’s choice in patients with metastatic breast cancer (EMBRACE): a phase 3 open-label randomised study. Lancet 2011;377:914–923.

- Rasmussen ML, Liposits G, Yogendram S, et al. Treatment with eribulin (halaven) in heavily pre-treated patients with metastatic breast cancer. Acta Oncol. 2014;53:1275–1277.

- Unger JM, Barlow WE, Martin DP, et al. Comparison of survival outcomes among cancer patients treated in and out of clinical trials. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106:dju002.

- Kessler L, Falato C, Margolin S, et al. A retrospective safety and efficacy analysis of the first patients treated with eribulin for metastatic breast cancer in Stockholm, Sweden. Acta Oncol. 2015;54:522–529.

- Tesch H, Schneeweiss A. Practical experiences with eribulin in patients with metastatic breast cancer. Anticancer Drugs. 2016;27:112–117.

- Kaufman PA, Awada A, Twelves C, et al. Phase III open-label randomized study of eribulin mesylate versus capecitabine in patients with locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer previously treated with an anthracycline and a taxane. JCO 2015;33:594–601.

- Pivot X, Marmé F, Koenigsberg R, et al. Pooled analyses of eribulin in metastatic breast cancer patients with at least one prior chemotherapy. Ann Oncol. 2016;27:1525–1531.

- Twelves C, Awada A, Cortes J, et al. Subgroup analyses from a phase 3, open-label, randomized study of eribulin mesylate versus capecitabine in pretreated patients with advanced or metastatic breast cancer. Breast Cancer (Auckl). 2016;10:77–84.