Abstract

Purpose: The health-related quality of life (HRQoL) outcomes after comprehensive surgical staging including infrarenal paraaortic lymphadenectomy in women with high-risk endometrial cancer (EC) are unknown. Our aim was to investigate the long-term HRQoL between robot-assisted laparoscopic surgery (RALS) and laparotomy (LT).

Patients and Methods: A total of 120 women with high-risk stage I-II EC were randomised to RALS or LT for hysterectomy, bilateral salpingoophorectomy, pelvic and infrarenal paraaortic lymphadenectomy in the previously reported Robot-Assisted Surgery for High-Risk Endometrial Cancer trial. The HRQoL was measured with the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30 (EORTC-QLQ-30) and its supplementary questionnaire module for endometrial cancer (QLQ-EN24) questionnaire. Women were assessed before and 12 months after surgery. In addition, the EuroQol Eq5D non-disease specific questionnaire was used for descriptive analysis.

Results: There was no difference in the functional scales (including global health status) in the intention to treat analysis, though LT conferred a small clinically important difference (CID) over RALS in ‘cognitive functioning’ albeit not statistically significant −6 (95% CI−14 to 0, p = .06). LT conferred a significantly better outcome for the ‘nausea and vomiting’ item though it did not reach a CID, 4 (95% CI 1 to 7, p = .01). In the EORTC-QLQ/QLQ-EN24, no significant differences were observed. Eq5D-3L questionnaire demonstrated a higher proportion of women reporting any extent of mobility impairment 12 months after surgery in the LT arm (p = .03).

Conclusion: Overall, laparotomy and robot-assisted surgery conferred similar HRQoL 12 months after comprehensive staging for high-risk EC.

Introduction

The surgical management of women with endometrial cancer (EC) confined to the uterus differs globally [Citation1]. Comprehensive surgical staging (including pelvic and paraaortic lymphadenectomy) may be performed in women with tumours considered to have a higher risk of lymphatic dissemination. Definition of lymphadenectomy as part of the staging procedure varies, and international standardisation is lacking.

It has been established that surgical staging, including pelvic and inframesenteric paraaortic lymphadenectomy, confers less moderate to serious postoperative adverse events and shorter hospital stay than laparotomy when performed as minimally invasive surgery (MIS) [Citation2]. Long-term health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in relation to surgical modality has been reported with diverging results [Citation3,Citation4]. The LAP2 trial showed no difference in HRQoL after 6 months between laparoscopy and laparotomy [Citation3] whereas Zullo et al. [Citation4] reported outcomes in favour of laparoscopy in all QoL domains at 6 months post-operatively. Neither trial included infrarenal paraaortic lymphadenectomy as part of their staging procedure.

Pelvic and infrarenal paraaortic lymphadenectomy in EC is performed for diagnostic purposes to better select or rather deselect patients without lymph node metastases from unnecessary adjvuant treatment, as two large RCTs have failed to demonstrate any therapeutic benefit. The balance between the risk of adverse events (including long-term HRQoL) and benefits of surgical lymph node assessment, must thus be considered when counselling women with EC. There are no previous studies reporting long-term HRQoL outcomes in women subjected to surgical staging including infrarenal paraaortic lymphadenectomy.

As previously reported from the Robot-Assisted Surgery for High-Risk Endometrial Cancer (RASHEC) trial, robot-assisted laparoscopic surgery (RALS) offers a similar infrarenal paraaortic lymph node count, lower health care cost and similar short-term complications rates compared to laparotomy (LT) [Citation5]. The present study aimed to evaluate long-term HRQoL after comprehensive surgical staging, including infrarenal paraaortic lymphadenectomy, and to investigate if there were differences in HRQoL related to surgical modality between RALS and LT.

Patients and methods

The RASHEC trial was a randomised controlled non-inferiority trial to compare infrarenal para-aortic lymph node yield between RALS and LT. The primary outcome was the number of harvested paraaortic lymph nodes. Women with early stage EC and high-risk features were randomly assigned to RALS or LT with the intention to undergo hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, pelvic and infrarenal paraaortic lymph node dissection. Of 120 included women, 113 was part of the intention to treat group and were analysed in this report. Mean pelvic and paraaortic lymph node count was 22 and 20 for RALS, 28 and 22 for LT [Citation5]. This study was approved by the Regional ethics committee at Karolinska Institutet. Informed consent was received from all patients.

Health-related quality of life

HRQoL was measured with the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30 (EORTC QLQ-C30) and its endometrial cancer supplementary questionnaire module (QLQ-EN24) [Citation6,Citation7]. The QLQ-C30 includes overall QoL (global health status), five functional scales (physical, role, emotional, cognitive and social), three symptom scales (fatigue, nausea/vomiting and pain), and six single items (dyspnoea, insomnia, appetite loss, constipation, diarrhea and financial difficulties). The EORTC QLQ-C30 is considered to have good psychometric qualities and has been validated in Swedish [Citation6,Citation8]. The supplementary module QLQ-EN24 includes three functional scales (sexual interest, sexual activity and sexual enjoyment), five symptom scales (lymphoedema, urological, gastrointestinal, poor body image and vaginal) and five single items (pain in back and pelvis, tingling/numbness, muscular pain, hair loss and taste change). The QLQ-EN24 supplementary module has also been validated in two international studies showing good psychometric qualities, the Swedish version of the questionnaire was part of the first validation study [Citation7,Citation9]. The response format for both questionnaires is from 1 (Not at all) to 4 (Very much), with the exception of two items in EORTC QLQ-C30 which are scored on a seven-point scale. A high score on the functional scales and global QoL represents a high level of functioning and QoL. A high score on the symptom scales/items represents a high level of symptoms.

The EuroQol EQ-5D-3L questionnaire measures non-disease specific health status [Citation10]. It encompasses five questions regarding ‘anxiety and depression’, ‘pain/discomfort’, ‘usual activity’, ‘self-care’ and ‘mobility’ with three levels of answers; ‘no problems’, ‘some problems’ and ‘extreme problems’. In the additional visual analogue scale (VAS), patients are asked to report their global health state in a scale from 0 to 100. The Swedish version of the questionnaire has been validated [Citation11].

The patients were asked to answer the above-mentioned questionnaires on paper before, and 12 months after, surgery. The questionnaires were either given to the patient at the clinic or sent home by conventional mail together with prepaid return envelopes.

Statistical method

Data for the EORTC QLQ-C30/QLQ-EN24 was scored according to the EORTC QLQ-C30 manual, missing values were treated accordingly [Citation12]. All scales were linearly transformed to range from 0 to 100. In the interpretation of the EORTC QLQ-C30/QLQ-EN24 scores, a difference of >5 points was considered clinically important for the patients, i.e., could be experienced by them [Citation13]. Differences of 5–9 points were considered small, those of 10–19 moderate, and >20 large [Citation14]. The effect of surgical modality on each of the scale scores at the 12-month assessment was evaluated using linear regression models including the type of operation (laparotomy, robot-assisted laparoscopic surgery) and baseline scale scores. Results from these models are presented as mean differences together with 95% confidence intervals. P-values from these models refer to Wald tests. A P-value of <.05 was considered significant. No adjustment was made for multiple comparisons. For the EuroQoL EQ-5D-3L answers were dichotomised to ‘not at all’ or ‘any extent’ and comparisons at the different assessment time points were made without adjustment for baseline, proportions were compared with Fisher’s exact test. For the EuroQol visual analogue scale (VAS), the median score at the assessment points by surgical modality was compared with Mann U Whitney test.

Results

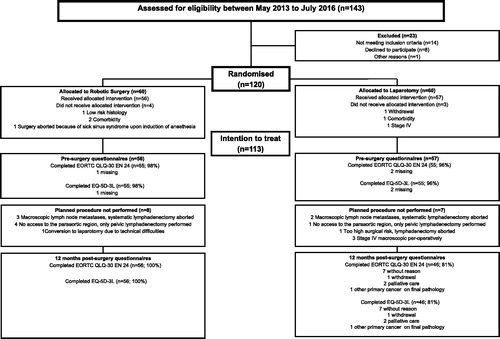

A total of 120 women were randomised equally between the arms, out of whom 113 received allocated treatment with an intention to treat. The EORTC-QLQ-C30 and QLQ-EN24 were answered at baseline by 98% (n = 55) of women in the RALS group and 96% (n = 55) in the LT group. The corresponding figures at 12 months were 100% (n = 56) and 81% (n = 46). The Consort diagram is presented in .

Baseline characteristics/demographics, perioperative outcome and postoperative treatment are presented in . The mean age was 66 and 64 years in the LT and RALS group, respectively. More women in the RALS group had higher level of education (41 vs. 25%). The majority of patients received adjuvant treatment, of which chemotherapy was most commonly used (44% LT and 38% RALS). Chemo-radiation was delivered to 23% in LT group and 30% in RALS group. No patient received external beam radiotherapy only. Women in the RALS arm had longer operation time (229 vs. 183 min) but postoperative 30-day serious adverse events were similar.

Table 1. Baseline demographics/characteristics and perioperative variables by surgical treatmenta.

The results of the EORTC-QLQ-C30 are presented in . There was a statistically significant difference between the groups 12-months after surgery for ‘nausea and vomiting’ in favour of laparotomy (p = .01), but the difference of 4 (95% CI 1 to 7) between the mean scores was not considered clinically important. Patients in the LT group reported clinically significantly higher, but statistically non-significant, cognitive functioning compared to RALS, −6 (95% CI −14 to 0, p = .06).

Table 2. EORTC QLQ-C30 scale scores at 12-months post-surgery by surgical modalitya.

The results of QLQ-EN24 are presented in . The largest difference found was for body image, where patients in the RALS group reported poorer body image 9 (95% CI −1 to 18, p < 0.07). However, no statistically significant difference was found between LT and RALS in any QLQ-EN24 scale.

Table 3. EORTC QLQ-EN24 scores at 12-months post-surgery by surgical modalitya.

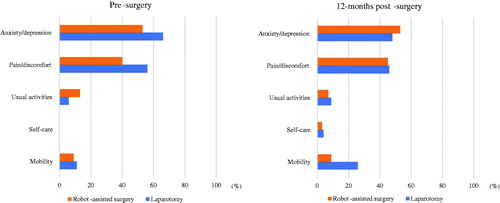

The EuroQoL EQ-5D-3L questionnaire was answered at baseline by 98% (n = 55) of women in the RALS group and 96% (n = 55) in the LT group. Corresponding figures at 12 months were 100% (n = 56) and 81% (n = 46), respectively (). At 12 months’ post-surgery, a larger proportion of women in the LT group reported any extent of impairment of mobility (26% vs. 9%, p = .03) as compared to the RALS group, but no other difference appeared (). There was neither a difference in the EQ-Visual Analogue Scale score between groups (80 in both groups, p = .94), data not shown.

Discussion

The RASHEC trial is the first randomized controlled trial comparing robot-assisted surgery to laparotomy for high-risk early stage EC staging, including infrarenal paraaortic lymph node dissection. In the present study of patient-reported HRQoL, no clinically relevant differences were found between the treatment arms, 1 year after surgery. These findings suggest that the choice of surgical modality has little or no impact on HRQoL in women with high-risk EC 1 year after surgery.

Two previous trials, that included mandatory surgical staging (i.e., lymphadenectomy) comparing surgical modalities in relation to HRQoL outcomes, have been conducted. The GOG LAP2 trial, where pelvic and inframesenteric paraaortic lymphadenectomy was performed, assessed HRQoL by the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy Scale-General (FACT-G) questionnaire [Citation2,Citation15]. The only significant difference in favour of laparoscopy at 6 months follow-up was body image, though no clinically important difference (CID) was met [Citation3]. In the study by Zullo et al., where pelvic lymphadenectomy was mandatory and paraaortic lymphadenectomy performed in 7%, the Short Form Health Survey 36 (SF-36) questionnaire was used. The authors observed favourable outcomes for laparoscopy in all domains of the questionnaire at 6 months, but measures of CIDs were not reported [Citation4,Citation16].

Based on the previous result of these studies, we expected to find significantly better HRQoL among women treated with RALS in our study. However, the only statistically significant difference in mean scores was observed in favour of LT for nausea/vomiting. The mean difference was small and did not meet CID [Citation14]. We, therefore, find it unlikely that this finding has any relevance for the treated women. Cognitive impairment has been reported after surgery, though the underlying mechanisms are not fully understood [Citation17]. Although not statistically significant, a small CID in cognitive functioning in favour of LT was observed in the current trial. The Trendelenburg position required for robot-assisted pelvic surgery might be associated with cerebral hypoxia, though reports are scarce [Citation18]. Furthermore, it is well known that chemotherapy may result in cognitive impairment [Citation19]. Whether this finding has any relevance must be further explored in larger trials.

Given that the only difference in HRQoL reported in the LAP2 trial was superior body image after MIS, we were surprised to find similar mean scores in both treatment arms in the current trial. The larger incision required by laparotomy to access the infrarenal area should reasonably lead to a poorer body image in the LT arm. On the contrary, a CID was apparent in favour of LT, although not statistically significant. Several studies support the results from the LAP2 trial, reporting better cosmetic satisfaction after MIS. Higher level of satisfaction with scar cosmesis does not, however, necessarily translate to better body image [Citation20–23]. It could be argued that a full midline scar is a constant visual reminder of the patient’s cancer diagnosis, which conceptualizes a different frame of reference that remains in the long-term. Further, the mean age in our study could reflect a different attitude and acceptance in elderly women. Finally, cultural differences between countries in which the studies were conducted may affect the response [Citation3,Citation24].

Statistically significantly fewer women in the RALS reported any extent of mobility impairment in the EuroQoL EQ5D-3L one year after surgery as compared to LT. Few women reported, however, any extent of impairment (LT n = 12, RALS n = 9). In addition, no between group differences were found for the other four questions including the EQ5D VAS score. The results should be interpreted cautiosly, especially since no adjustments for baseline score were made.

Possible explanations for the observed differences in HRQoL between the current and previous trials include the duration of follow-up and the extent of surgical staging. In both the LAP2 and the trial by Zullo et al., 6 months follow-up were used whereas our long-term assessment encompasses the end of adjuvant treatment, with follow up 12 months after surgery. It is possible that the favourable HRQoL outcomes reported in the previous trial would have been less apparent 6 months later. Whether the more extensive staging procedure applied in the current study mitigates the effect of minimally invasive access on HRQoL remains speculative.

The strengths of our study include the prospective, randomised design and the high response rate to the questionnaires at each assessment point. The study was a single institution trial, with a limited number of surgeons and exact definitions of the surgical procedures, resulting in a high internal validity. There are, however, also limitations. The HRQoL analysis was a secondary endpoint from the RCT and thus not powered to detect potential differences. Therefore, we cannot exclude the risk of type II-errors for questions with borderline significance (body image and cognitive dysfunction).

In conclusion, the results of our study suggest that HRQoL 1 year after comprehensive surgical staging, including infrarenal paraaortic lymphadenectomy, in women with EC is not affected by surgical modality. From a HRQoL prespective, the choice of abdominal access should be based on patient’s preference and surgeon’s experience.

Acknowledgements

All participating patients. Dyllis Nordman Bergström, coordinator of the Gynecologic oncology surgical ward and all members of staff at the Surgical Gynaecologic Oncology services at Karolinska University Hospital.

Disclosure statement

Henrik Falconer is a Proctor for Intuitive Surgical. The remaining authors declare no conflict of interest in regard to this paper.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Fotopoulou C, Kraetschell R, Dowdy S, et al. Surgical and systemic management of endometrial cancer: an international survey. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2015;291(4):897–905.

- Walker JL, Piedmonte MR, Spirtos NM, et al. Laparoscopy compared with laparotomy for comprehensive surgical staging of uterine cancer: Gynecologic Oncology Group Study LAP2. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(32):5331–5336.

- Kornblith AB, Huang HQ, Walker JL, et al. Quality of life of patients with endometrial cancer undergoing laparoscopic international federation of gynecology and obstetrics staging compared with laparotomy: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(32):5337–5342.

- Zullo F, Palomba S, Russo T, et al. A prospective randomized comparison between laparoscopic and laparotomic approaches in women with early stage endometrial cancer: a focus on the quality of life. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193(4):1344–1352.

- Salehi S, Avall-Lundqvist E, Legerstam B, et al. Robot-assisted laparoscopy versus laparotomy for infrarenal paraaortic lymphadenectomy in women with high-risk endometrial cancer: a randomised controlled trial. Eur J Cancer. 2017;79:81–89.

- Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85(5):365–376.

- Greimel E, Nordin A, Lanceley A, et al. Psychometric validation of the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire-Endometrial Cancer Module (EORTC QLQ-EN24). Eur J Cancer. 2011;47(2):183–190.

- Sigurdardottir V, Brandberg Y, Sullivan M. Criterion-based validation of the EORTC QLQ-C36 in advanced melanoma: the CIPS questionnaire and proxy raters. Qual Life Res. 1996;5(3):375–386.

- Stukan M, Zalewski K, Mardas M, et al. Independent psychometric validation of European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire-Endometrial Cancer Module (EORTC QLQ-EN24). Eur J Cancer Care. 2018;27(1).

- Rabin R, de Charro F. EQ-5D: a measure of health status from the EuroQol Group. Ann Med. 2001;33(5):337–343.

- Burstrom K, Sun S, Gerdtham UG, et al. Swedish experience-based value sets for EQ-5D health states. Qual Life Res. 2014;23(2):431–442.

- Fayers PM. AN, Bjordal K., Groenvold M., Curran D., Bottomley A. EORTC QLQ-C30 Scoring Manual. 3rd ed. Brussels: European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer; 2001.

- Cocks K, King MT, Velikova G, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for interpreting change scores for the European Organisation for the Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48(11):1713–1721.

- Osoba D, Rodrigues G, Myles J, et al. Interpreting the significance of changes in health-related quality-of-life scores. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16(1):139–144.

- Cella DF, Tulsky DS, Gray G, et al. The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy scale: development and validation of the general measure. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11(3):570–579.

- Ware JE, Jr., Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Medical care. 1992;30(6):473–483.

- Selnes OA, Gottesman RF, Grega MA, et al. Cognitive and neurologic outcomes after coronary-artery bypass surgery. New Engl J Med. 2012;366(3):250–257.

- Ozgun A, Sargin A, Karaman S, et al. The relationship between the Trendelenburg position and cerebral hypoxia inpatients who have undergone robot-assisted hysterectomy and prostatectomy. Turk J Med Sci. 2017;47(6):1797–1803.

- Li M, Caeyenberghs K. Longitudinal assessment of chemotherapy-induced changes in brain and cognitive functioning: a systematic review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2018;92:304–317.

- Yuen PM, Yu KM, Yip SK, et al. A randomized prospective study of laparoscopy and laparotomy in the management of benign ovarian masses. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;177(1):109–114.

- Zhang L, Sah B, Ma J, et al. A prospective, randomized, controlled, trial comparing occult-scar incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy and classic three-port laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 2014;28(4):1131–1135.

- Quattrone C, Cicione A, Oliveira C, et al. Retropubic, laparoscopic and mini-laparoscopic radical prostatectomy: a prospective assessment of patient scar satisfaction. World J Urol. 2015;33(8):1181–1187.

- Park SK, Olweny EO, Best SL, et al. Patient-reported body image and cosmesis outcomes following kidney surgery: comparison of laparoendoscopic single-site, laparoscopic, and open surgery. Eur Urol. 2011;60(5):1097–1104.

- Janda M, Gebski V, Brand A, et al. Quality of life after total laparoscopic hysterectomy versus total abdominal hysterectomy for stage I endometrial cancer (LACE): a randomised trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11(8):772–780.