Abstract

Background: Fast-track referral is an increasingly used method for diagnostic evaluation of patients suspected of having cancer. This approach is challenging and not used as often for patients with only nonspecific symptoms. In order to expedite the diagnostics for these patients, we established Sweden’s first Diagnostic Center (DC) focusing on outcomes related to diagnoses and diagnostic time intervals.

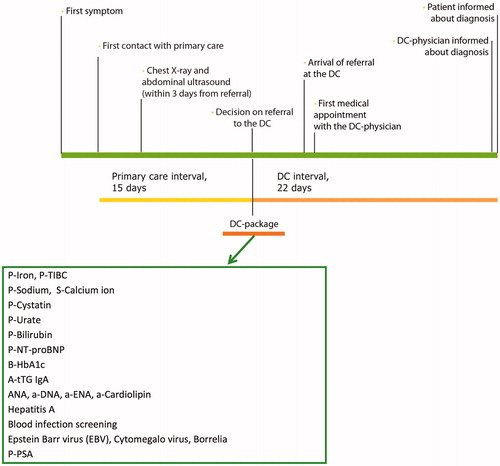

Material and Methods: The study was designed as a prospective cohort study. Patients aged ≥18 years who presented in primary care with nonspecific symptoms of a serious disease were eligible for referral to the DC after having completed an initial investigation. Acceptable diagnostic time intervals were defined to be a maximum of 15 days in primary care and 22 days at the DC. Diagnostic outcome, length of diagnostic time intervals and patient satisfaction were evaluated.

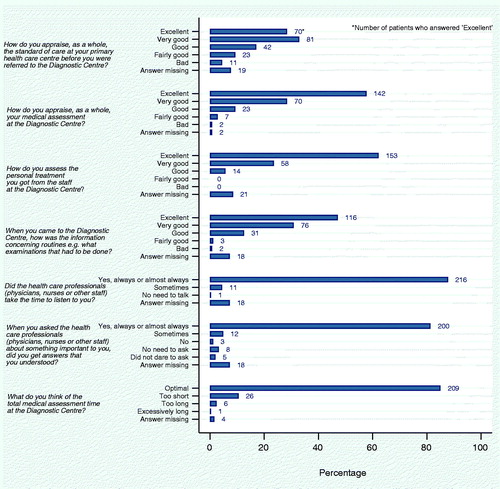

Results: A total of 290 patients were included in the study. Cancer was diagnosed in 22.1%, other diseases in 64.1%, and no diagnosis was identified in 13.8% of these patients. Patients diagnosed with cancer were older, had shorter patient interval (time from first symptom to help-seeking), shorter DC-interval (time from referral decision in primary care to diagnosis) and showed a greater number of symptoms compared to patients with no diagnosis. The median primary care interval was 21 days and the median DC interval was 11 days. Few symptoms, no diagnosis, female sex, longer patient interval, and incomplete investigations were associated with prolonged diagnostic time intervals. Patient satisfaction was high; 86% of patients reported a positive degree of satisfaction with the diagnostic procedures.

Conclusions: We demonstrated that the DC concept is feasible with a diagnosis reached in 86.2% of the patients in addition to favorable diagnostic time intervals at the DC and a high degree of patient satisfaction.

Trial registration: ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01709539.

Introduction

Most patients who subsequently will be diagnosed with cancer have initially seen a family physician. Delayed diagnostics increases the psychological burden for patients and has, in several cancer types, been associated with an adverse prognosis [Citation1–5]. Hence, expedited referrals from family physicians have the potential to positively influence survival rates in a number of cancer types [Citation6]. Interventions to reduce diagnostic time intervals need to address patient-related as well as system-related factors; this has been documented in a comparative study between England, Denmark and Sweden [Citation7]. To achieve expedited diagnoses and more timely initiation of treatment, diagnostic pathways for patients with a predefined set of symptoms have been implemented in several countries. Fast-track referral pathways for patients with suspected cancer were introduced in the UK in the early 2000’s and similar systems (referred to as cancer patient pathways) were introduced in Denmark in 2008 and in Norway in 2015 [Citation8–10]. Although Sweden, in a global comparison, has one of the highest cancer survival rates [Citation11,Citation12], the healthcare system lags behind in international benchmarking evaluations; this can largely be explained by insufficient access to care, long diagnostic time intervals, and suboptimal patient satisfaction reports [Citation13] Awareness of these issues led to the implementation of 28 standardized care pathways for cancer between 2015 and 2018 [Citation14].

Fast-track referral is typically based on alarm symptoms such as macroscopic hematuria, rectal bleeding or a lump in the breast, but only about half of the patients in primary care showed such symptoms [Citation15,Citation16]. In primary care, many patients with cancer show only general or nonspecific symptoms, such as fatigue, weight-loss, fever, or anemia [Citation16,Citation17] and fast-track referral is less likely for these latter subgroups [Citation18]. Results from five case-control studies in the UK (the CAPER studies) confirm that many patients with common cancers do not have evident alarm symptoms, but low-risk symptoms, and may thus not qualify for urgent referral [Citation19].

Higher five-year mortality has been associated with nonspecific symptoms and prolonged diagnostic intervals for lung cancer, malignant melanoma, and prostate cancer [Citation5]. Thus, interventions directed at patients with nonspecific symptoms are needed to reduce the time from first symptom to diagnosis and subsequent treatment. In Denmark, the first diagnostic center (DC) aimed at inter-disciplinary and inter-sectorial patient pathways was initiated in 2009 followed by further national implementation in 2012 [Citation20,Citation21]. In the UK, a new Suspected CANcer (SCAN) pathway for patients with ‘low-risk but not no-risk’ is currently being evaluated [Citation22]. Early positive reports from Denmark led us in 2011 to begin developing a model for the first DC in Sweden. The project group consisted of specialists in family medicine, clinical chemistry, gynecology and obstetrics, pathology, radiology and a nurse. Patients with a set of defined nonspecific symptoms were eligible for DC-investigation, which included a standardized laboratory and radiology package. The time goals for the investigations were decided in collaboration with the primary healthcare centers and based on what could be expected in optimal cases including reasonable time intervals for laboratory analyses, biopsies, imaging and consultations with other medical specialists. The aim of our study was to investigate the diagnostic spectrum, diagnostic time intervals, feasibility, and patient satisfaction at the DC.

Material and methods

Diagnostic center setting

The DC was physically established in October 2012 at the Central Hospital of Kristianstad as a separate outpatient unit within the Department of Internal Medicine. It was located next-door to the Department of Radiology and Imaging thus facilitating a close collaboration between the units. The DC was staffed with a half-time physician specialized in internal medicine and family medicine, a full-time nurse and a full-time medical secretary. The catchment area initially comprised 25 primary healthcare centers and was gradually extended to 42 centers; this encompassed a catchment area of 220,000 inhabitants in the eastern part of the county.

Ensuring that family physicians were aware of the DC and getting routines to work were identified as key factors in the project planning and described in the risk analysis as likely risks with serious consequences. A communication plan was developed in collaboration with the primary healthcare centers. The implementation was then commenced in 2012 with information meetings with family physicians and nurses. Written information was distributed to all primary healthcare centers. The primary care representative in the project group continued throughout the study to visit the primary healthcare centers to remind staff about the DC during the project.

Eligibility criteria

We performed a prospective cohort study of patients that had been referred to the DC from primary care. Data collection was initiated at the start and was scheduled to last until 60 patients with cancer were included, which occurred in September 2015. The stipulated goal of 60 patients with cancer was based on an expectation of 300 patients needed for proper analyses of the laboratory tests. At the time of project planning, preliminary data from Denmark suggested a 20% prevalence of cancer, which corresponds to 60 patients in our study.

At the first DC visit, all patients who could provide informed consent based on oral and written study information in Swedish were invited to participate in the study. Reasons for exclusion were collected in a screening log that was reviewed by a study nurse.

Family physicians were invited to refer patients 18 years or older to the DC. Inclusion criteria were adopted from Denmark and included one or more of the following criteria: (1) fatigue, (2) weight loss more than 5 kg, (3) pain/joint pain, (4) prolonged fever, (5) pathological lab values or (6) suspected metastasis [Citation23].

The complete diagnostic interval, from first contact with primary care to diagnosis, comprised of two phases: (1) the primary care interval, from first contact with primary care to decision about referral to the DC and (2) the DC interval, from referral decision in primary care to diagnosis. The terms ‘diagnostic interval’ and ‘primary care interval’ were modified from The Aarhus statement 2012 [Citation24].

The study was approved by the Regional Ethics Committee in Lund, Sweden (registry number 2012/449) and was registered in ClinicalTrials.gov (registry number: NCT01709539).

Logistics of the diagnostic fast-track pathway

Primary care interval: diagnostic workup in primary care (≤15 working days)

Patients in primary care that met one or more of the referral criteria, without focal symptoms, were offered an appointment with a family physician within two to three working days after their first contact with the center. The investigation included a medical history, a clinical examination and a standardized set of laboratory tests. In cases when the diagnosis was still unclear, these tests were followed by a second set of tests. Diagnostic workup in primary care also included chest X-ray and abdominal ultrasound to be scheduled within three working days from referral. If focal symptoms or signs of specific disease were found during the diagnostic workup in primary care, the patients were referred to a respective medical specialist or standardized care pathway. These patients were not included in the study. If no reasonable explanation for the patient's symptoms was found, the patient was eligible for referral to the DC. This was done via phone call and written referral. In conjunction with the referral, a standardized panel of laboratory tests (the DC-package; ) was taken; the results were sent directly to the DC.

DC interval: diagnostic workup at the DC (≤22 working days)

Patients should be offered an appointment with the DC-physician within three working days post referral. Guided by the medical history, the following were performed: a thorough physical examination, evaluation of the results from the DC-package and appropriate further investigations, including consultations with other specialists. The aim of these investigations was to have a resulting diagnosis within 22 working days. Upon evaluation at the DC being completed, the study participants were asked to fill in a questionnaire about individual profile, time from first symptoms to first primary care contact, and patient-reported experiences.

Data collection

Data on time intervals, symptoms, investigations, comorbidity, drugs, and diagnoses were collected and documented in case report forms, which were monitored and validated by a study nurse using original data from the patient’s files. Investigation times were evaluated via a number of registration points during the diagnostic trajectory (). Phase 1 (primary care interval) was defined as the time from first contact with primary care until referral to the DC. Phase 2 (DC interval) was defined as the time from referral decision at the primary healthcare center to the date when the patient was informed about the outcome of the diagnostic process and hence received a diagnosis. In individuals with multiple diagnoses, diagnostic time intervals were calculated differently for patients with and without cancer (stop date defined as the date of the latest diagnosis, or the date of first cancer diagnosis).

The symptoms that led to referral from the family physicians were collected from the referrals. In the case report forms, the DC-physician was able to comment on the investigations. Documented reasons for prolonged investigation times were categorized into six explanatory groups.

Statistical analysis

Age is presented as median and interquartile range (IQR), while sex, education, marital status, country of birth and diagnoses at the DC are presented as numbers and percentages. Investigation times are presented as mean and standard deviation (SD) together with percentiles. Number of days refers to number of working days and the first day of the interval (day zero) counts as one day. Fulfilment of time goals were calculated as proportion that was investigated within expected time frames. To examine differences between patients diagnosed with cancer, patients diagnosed with other diseases and patients with no diagnosis, we used Chi-square test or Fishers exact test for the categorized variables and Wilcoxon rank-sum test for the other variables. Corresponding tests were used to examine differences between patients who fulfilled time goals and those who did not, as well as between the 10% shortest and 10% longest time intervals. Data concerning survival rates for patients with cancer were obtained from the Swedish Cancer Registry and presented as median survival and survival rates, both with 95% confidence intervals (CI). All statistical analyses were done in STATA version 14 (StataCorp LP).

Results

Study participants: basic characteristics, diagnoses, and referral criteria

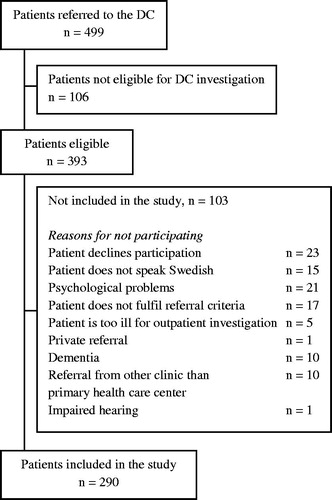

During the study period, 499 patients were referred to the DC of whom 393 were eligible for diagnostic investigations at the DC and 290 were eligible for study inclusion (). Of the included patients, 51.4% were women and the median age was 69 years (IQR 16.6).

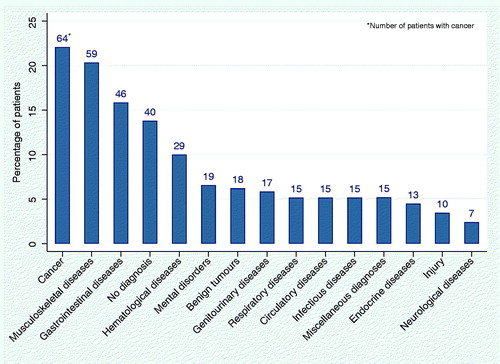

A total of 64 patients (22.1%) were diagnosed with cancer at the DC, thus making malignancies the most common diagnostic group. There were 186 patients (64.1%) diagnosed with nonmalignant diseases. A total of 73 patients (25.2%) had multiple diagnoses belonging to different diagnostic groups (). In 40 patients (13.8%), no diagnosis was found.

Table 1. Patient characteristics.

A graph showing all diagnostic groups is shown in . Among other diagnoses than cancer, musculoskeletal diseases were the most common affecting 59 (20%) of all patients including 46 cases of autoimmune or degenerative joint diseases. A total of 46 (16%) patients were diagnosed with gastrointestinal diseases, and 29 patients (10%) had hematological diseases, 25 of which had anemia. A total of 89% of the patients had a history of previous diagnoses of importance for the DC-investigation (as judged by the DC-physician) and the median number of previous diagnoses of importance was 2 (IQR 2).

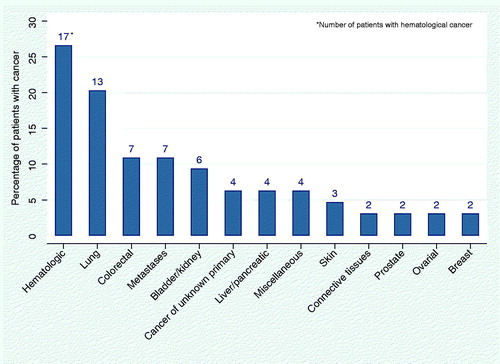

In 79 (27%) patients, the diagnosis set at the DC was part of the patient’s medical history and in 6 (9%) of the 64 cancer patients, the diagnosis reached was related to a previous cancer diagnosis, e.g. relapse in colon cancer or malignant melanoma. The most common malignant diagnoses were hematological diseases, followed by lung cancer, colorectal cancer, and metastases (). Of the patients with cancer, 30 (47%) had infiltrating tumors (solid tumors with potential to spread based on TNM-staging) and 13 (20%) were referred to palliative care. Among patients diagnosed with cancer, the median survival time after diagnosis was 1.4 years (CI 0.7–2.8). The 1-year survival rate was 0.55 (CI 0.42–0.67) and the 3-year survival rate was 0.36 (CI 0.23–0.48).

The most common referral criteria for all patients were pathological laboratory values, weight loss, fatigue, and pain/joint pain. The other two recommended referral criteria, prolonged fever and suspected metastasis, were less common although suspected metastasis was more frequent among patients diagnosed with cancer compared to patients with other diagnoses and no cancer diagnosis (p = .01 and .046 respectively). Patients with cancer had more pathological lab values compared to patients with no diagnosis (p = .02) (). Although not intended for DC-investigation, there were occasional alarm symptoms in the referrals from the primary healthcare centers among patients with cancer; one case of hematuria, two cases of changed bowel habits and one case of dysphagia.

Table 2. Diagnoses at the DC.

Patients diagnosed with cancer tended to have more symptoms at referral compared to patients who were not diagnosed with cancer, with a statistically significant difference when compared to patients with no diagnosis (p < .0001) (). It was the group with advanced cancer disease that was driving this trend: patients with infiltrating tumors had more symptoms than patients with non-infiltrating tumors or hematological cancers (p = .01) (data not shown).

During diagnostic workup at the DC, classical alarm symptoms emerged in 26 patients that were later diagnosed with cancer. These symptoms were, however, not necessarily associated with respective cancer form. Fecal blood was found in one patient with colon cancer, three patients with urinary tract cancer had hematuria, a lump was found in seven patients with cancer (different forms), changed bowel habits were reported by a patient with pancreatic cancer, swollen lymph nodes were detected in five patients with cancer (different forms) and an uneven prostate was detected at inspection in one patient with prostate cancer. In addition, 36 patients with cancer were found to have anemia, which is a general high risk symptom.

Patients diagnosed with cancer were older than patients with no diagnosis (69.8 (IQR 11.3) and 63.4 (IQR 14.5) respectively, p = .01) and they had shorter patient intervals (as assessed by the questionnaire: sought care within three months from first symptom) compared to patients with no diagnosis (44% and 25% respectively, p = .01) ().

Of all patients, a total of 36% had completed the full DC-package in primary care prior to referral to the DC. Radiology before referral should consist of chest X-ray, which was performed in 66% of patients and abdominal ultrasound, which was performed in 57% of patients. A minority of the patients (28%) had completed all recommended investigations prior to DC referral. In the DC-package, the most common samples to take were P-Sodium (66%) and P-PSA (65% of men), whereas less than 40% of the patients were tested for Hepatitis A, blood infection, Epstein-Barr virus and Cytomegalovirus infections (data not shown).

Time intervals

shows the length of the primary care interval, the DC interval and the total diagnostic interval, expressed as mean number of working days, standard deviations (SD) and percentiles. The date for the first contact with primary care was difficult to obtain with missing data in 116/290 (40%) cases. The mean investigation time in primary care (phase 1) was 32.6 (SD 37.5) days and the median time was 21 days. The mean investigation time at the DC (phase 2) was 17.1 (SD 17.9) days; the median time was 11 days. For the total diagnostic interval, the mean investigation time was 46.8 (SD 36.1) days and the median time was 37 days. In primary care, 72/174 (41.4%) of the patients were investigated within the scheduled time frame of 15 days. At the DC, 221/286 (77.3%) were investigated within the scheduled time frame of 22 days, and 87/171 patients (50.9%) were investigated within the total scheduled time frame of 37 days, i.e. from first contact in primary care to diagnosis at the DC. Among patients who were diagnosed with cancer, 45% fulfilled the time goals in primary care, 83% at the DC and 56% fulfilled the total time goal of 37 days (data not shown). A sensitivity analysis - in which time for the most recent diagnosis was used for all patients - was performed and this did not influence the findings.

Table 3. Number of days in each investigational phase (working days).

In Supplementary Tables S1–S3, comparisons between investigations that achieved the time goals with those who did not are shown. There are also comparisons between the 10% longest and the 10% shortest investigation times. The DC-physician’s documented reasons for long diagnostic intervals are presented in Table S2.

Factors associated with the length of the primary care interval

In primary care, there was a significant association between fulfilling the time goal (≤15 days) and taking the complete DC-package (48.6% versus 30.4%, p = .02), and also with the number of symptoms (p = .03) (Table S1). When examining the 10% longest and 10% shortest primary care intervals, patient interval was identified as a major factor; among patients with the longest investigation times in primary care, only one (5.3%) contacted the primary healthcare center within three months from the first symptom compared to 65% among those with the shortest investigation times (p < .001).

Factors associated with the length of the DC interval

No statistically significant associations were found when comparing investigations that achieved time goals at the DC with those who did not (Table S2).

When comparing the 10% longest with the 10% shortest investigation times at the DC, factors that emerged with statistical significance were female sex and getting no diagnosis: women were in majority among patients with the longest investigations and in minority among patients with the shortest investigations (62% and 34% respectively; p = .03). A total of 24.1% of patients with the longest investigation times did not get a diagnosis as compared to only 2.9% of patients with the shortest investigation times (p = .01). Among patients with prolonged DC intervals (>22 days), there were, in many cases, documented reasons, such as waiting times at other clinics or need of observation time (Table S2).

Factors associated with the length of the total diagnostic interval

For the total diagnostic interval (primary care + DC), taking the complete DC-package was significantly associated with fulfilling the time goal (p = .03) (Table S3). Short patient interval (seeking care within three months) was significantly more common in the group with the 10% shortest investigations compared to the 10% longest (p = .02).

Patient experiences

Patients (n = 246) expressed a high degree of satisfaction with their DC fast-track referral () with 86% valuing their investigation at the DC as very good or excellent. A total of 86% of patients answered that the treatment by the healthcare staff was very good or excellent and 78% judged the information given to be very good or excellent. A total of 88% of patients felt listened to (always or almost always) and 81% always or almost always understood answers to their questions. A total of 85% of patients answered that the investigation time at the DC was satisfactory, 2.4% remarked that it was too long, and 10.6% thought that it was too short.

Discussion

Our study evaluated the results of the first Swedish DC. The center was established in 2012 in response to a lack of formal diagnostic pathway for patients with nonspecific symptoms of serious disease, who were at risk of medically unjustified delayed cancer diagnosis. Since 2016, the concept has developed into a standardized care pathway for cancer. Today, more than 20 DCs are distributed across Sweden. In Denmark, where the concept was originally developed, each of the five regions has at least one DC. In Norway, development of DCs is part of the cancer strategy.

Using predefined referral criteria and a diagnostic package, we demonstrated that 22% of the patients were diagnosed with cancer with stable results during the study period. In evaluations of the Danish model, 13-22% of the patients were diagnosed with cancer [Citation20,Citation21,Citation25] and the aim is for a continuing decrease [Citation20]. The constant 22% cancer prevalence at the Swedish DC may be a sign that family physicians can pinpoint the ‘right’ patients, but it might also indicate that more patients need to be referred. Using the present criteria for referral, the chance of detecting cancer may, however, be limited since nonspecific, serious, symptoms often occur when the cancer is advanced. Of the patients diagnosed with cancer at the DC, 47% had infiltrating tumors, which was reflected in the referral of 13 patients (20%) directly to specialized palliative care and a 3-year overall survival rate of 36%. Earlier detection of cancer may require other strategies such as screening and efforts to improve awareness in the population about early symptoms of cancer. Patients with an adverse prognosis and a short remaining life span still belong to the DC’s target groups and herein timely management with efficient access to supportive and palliative care that reduces symptoms and improves quality of life. Patients who are investigated without any diagnosis identified represent another important target group that benefits from the efficient and multidisciplinary diagnostic workup that the DC concept offers. Exclusion of defined and treatable diagnoses may allow for other interventions such as physical activity or coping strategies.

The tumor spectrum and the median age at diagnosis in our study were similar to the results from the Danish DC evaluations [Citation20,Citation21]. Among the cancers diagnosed, hematologic malignancies, lung cancer and colorectal cancer predominated; these findings concurred with the DC-findings in Denmark [Citation20]. The symptom spectrum identified was also comparable to that observed at the Danish DCs with weight loss, fatigue and pain among the five most common symptoms that were noted [Citation20,Citation21,Citation25]. The symptoms agreed with the recommended referral criteria and their appropriateness was confirmed by a previous questionnaire survey about family physicians’ views on the DC-project, in which 88% of the responders thought the referral criteria to be adequate (published in Swedish only). A possibility worthy of further exploration relates to the potential among family physicians to define serious disease by clinical intuition and to mark this as a criterion for further diagnostic evaluation. Studies have shown that family physicians’ gut feeling, or intuition, can be highly predictive of cancer in patients with nonspecific symptoms as well as palpable tumors and abdominal symptoms and that the ability improves with the physician’s age and experience. [Citation21,Citation26,Citation27]. Consultancy frequency represents another criterion of interest for further study; an increased frequency of consultancies has been documented during the year prior to a diagnosis of cancer [Citation28,Citation29]. This criterion has been included among the Danish cancer patient pathway referral criteria for patients with nonspecific symptoms [Citation23].

The time goal of ≤22 days for the DC interval was reached in the majority of patients, whereas the time goal of ≤15 days for the primary care interval was reached only in a minority of the investigations. Thus, in primary care, there may be room for improvement regarding diagnostic time intervals as well as adherence to the recommended workflow. Following the Danish experience with the purpose of shortening investigation times, the DC-package was introduced in the design of the project. However, taking a predetermined set of samples without specific indications was much questioned among healthcare managers and family physicians, whose traditional view is that each test or examination should be ordered from a specific clinical suspicion or question. This reluctance may explain the low rate of complete DC-packages taken. But taking the complete DC-package turned out to be associated with shorter diagnostic intervals in our evaluation and may be a helpful complement in the diagnostic process of this patient group. This is supported by observations that the probability of cancer in patients with nonspecific, serious symptoms increased with an increasing number of abnormal blood tests in a pre-defined blood test panel [Citation30]. Thus, further optimization and evaluation is needed to define the best possible package. Considering the challenge of implementing a new model at 42 primary healthcare centers, both private and public, a time goal-fulfillment of 41% may be a reasonable interim result, but with continuous communication and a streamlined model that is well anchored among the family physicians, the share can hopefully increase.

In our study, patients diagnosed with cancer were older, sought care earlier, and showed a greater number of symptoms compared to patients with no diagnosis. The DC-intervals were, on average, shorter for patients diagnosed with cancer. Additional analyses showed that few symptoms, longer patient intervals and lack of a final diagnosis were associated with prolonged diagnostic intervals. It may be worth considering if the time goals for diagnostic centers should target all referred patients or if investigations can be slightly prolonged when cancer or other life threatening disease has been ruled out.

A majority of the patients expressed positive experiences from the DC-evaluation. They felt, in general, listened to and understood the answers they got to their questions. A slightly lesser share valued their care at the primary healthcare center as excellent compared to the DC. This is not surprising, though, when you consider that the DC had time and resources earmarked for the patient population. The previously mentioned family physician questionnaire showed that 94% of the responders thought the DC to be advantageous for patients and that 92% thought it to be advantageous for the family physicians themselves. We choose to complement the evaluation with ‘soft values’ via questionnaires since this is an important part of the implementation process—the patients’ and healthcare providers’ points of view should be, and are, central in decisions about future priorities in healthcare. To get a deeper understanding of patients and family physicians’ opinions, individual or focus group interviews could be useful.

Strengths and limitations

A strength of the present study is the prospective design and the consecutive inclusion of all patients referred to the DC, irrespective of diagnosis. Data were continuously collected and monitored. Since several analyses were performed in a relatively heterogeneous patient material, some subgroups were of limited size. Another limitation is related to the difficulty to collect data from primary care and thus the uncertainty on date of first contact for which lack of records implied missing data.

Conclusions

Our evaluation demonstrates that the DC concept represents a well-functioning diagnostic pathway for patients with nonspecific, potentially serious symptoms. A diagnosis was reached in 86.2% of the patients and the time goal for investigation at the DC was achieved in a majority of the patients although the primary care intervals may still be shortened. A revision of the model for the initial investigation should therefore be considered. The diagnostic spectrum, patient characteristics and frequency of cancer, along with a high degree of patient satisfaction verify the feasibility of the DC concept.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (38.5 KB)Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Annika Bujukliev, nurse, and Mona Fransson, medical secretary at the DC for their invaluable efforts during the whole project. We thank family physician Annika Åkerberg for help with implementing the DC in primary care and monitoring nurse Marie Mårtensson Ruscic for meticulous review of all study related data. We also thank scientific editor Patrick Reilly for proof reading the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Hansen RP, Vedsted P, Sokolowski I, et al. Time intervals from first symptom to treatment of cancer: a cohort study of 2,212 newly diagnosed cancer patients. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11:284.

- Neal RD, Tharmanathan P, France B, et al. Is increased time to diagnosis and treatment in symptomatic cancer associated with poorer outcomes? Systematic review. Br J Cancer. 2015;112: S92–S107.

- Richards MA, Westcombe AM, Love SB, et al. Influence of delay on survival in patients with breast cancer: a systematic review. Lancet. 1999;353:1119–1126.

- Rutqvist LE. Waiting times for cancer patients–a "slippery slope" in oncology. Acta Oncol. 2006;45:121–123.

- Torring ML, Frydenberg M, Hansen RP, et al. Evidence of increasing mortality with longer diagnostic intervals for five common cancers: a cohort study in primary care. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49:2187–2198.

- Moller H, Gildea C, Meechan D, et al. Use of the English urgent referral pathway for suspected cancer and mortality in patients with cancer: cohort study. BMJ. 2015;351:h5102.

- MacArtney J, Malmstrom M, Overgaard Nielsen T, et al. Patients' initial steps to cancer diagnosis in Denmark, England and Sweden: what can a qualitative, cross-country comparison of narrative interviews tell us about potentially modifiable factors? BMJ Open. 2017;7:e018210.

- Department of Health. The NHS Cancer Plan. A Plan for Investment, a Plan for Reform. London, UK.: Department of Health; 2000.

- Gilstad H. Online Information about Cancer Patient Pathways (CPP) in Norway. eTELEMED 2016: The Eighth International Conference on eHealth, Telemedicine, and Social Medicine; Venice, Italy 2016.

- Vedsted P, Olesen F. A differentiated approach to referrals from general practice to support early cancer diagnosis - the Danish three-legged strategy. Br J Cancer. 2015;112:S65–S69.

- Allemani C, Matsuda T, DiCarlo V, et al. Global surveillance of trends in cancer survival 2000–14 (CONCORD-3): analysis of individual records for 37 513 025 patients diagnosed with one of 18 cancers from 322 population-based registries in 71 countries. Lancet. 2018;391(10125):1023–1075.

- Coleman MP, Forman D, Bryant H, et al. Cancer survival in Australia, Canada, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, and the UK, 1995–2007 (the International Cancer Benchmarking Partnership): an analysis of population-based cancer registry data. Lancet 2011;377:127–138.

- Björnberg A. Euro Health Consumer Index 2017. In: Health Consumer Powerhouse Ltd., editor. 2018.

- The National Board of Health and Welfare. Standardiserade vårdförlopp i cancervården. Lägesrapport 2017 [Standardized care pathways in cancer care. Progress report 2017]. Stockholm, Sweden: The National Board of Health and Welfare; 2017.

- Ingebrigtsen SG, Scheel BI, Hart B, et al. Frequency of 'warning signs of cancer' in Norwegian general practice, with prospective recording of subsequent cancer. Fam Pract. 2013;30:153–160.

- Jensen H, Torring ML, Olesen F, et al. Cancer suspicion in general practice, urgent referral and time to diagnosis: a population-based GP survey and registry study. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:636.

- Nielsen TN, Hansen RP, Vedsted P. [Symptom presentation in cancer patients in general practice]. Ugeskr Laeg. 2010;172:2827–2831.

- Zhou Y, Mendonca SC, Abel GA, et al. Variation in 'fast-track' referrals for suspected cancer by patient characteristic and cancer diagnosis: evidence from 670 000 patients with cancers of 35 different sites. Br J Cancer. 2018;118:24–31.

- Hamilton W. The CAPER studies: five case-control studies aimed at identifying and quantifying the risk of cancer in symptomatic primary care patients. Br J Cancer. 2009;101:S80–S86.

- Bislev LS, Bruun BJ, Gregersen S, et al. Prevalence of cancer in Danish patients referred to a fast-track diagnostic pathway is substantial. Danish Medical J. 2015;62(9):A5138.

- Ingeman ML, Christensen MB, Bro F, et al. The Danish cancer pathway for patients with serious non-specific symptoms and signs of cancer-a cross-sectional study of patient characteristics and cancer probability. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:421.

- Nicholson BD, Oke J, Friedemann Smith C, et al. The Suspected CANcer (SCAN) pathway: protocol for evaluating a new standard of care for patients with non-specific symptoms of cancer. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e018168.

- The National Board of Health Copenhagen. Diagnostisk pakkeforløb for patienter med uspecifikke symptomer på alvorlig sygdom, der kunne vaere kraeft [Diagnostic pathway for patients with non-specific symptoms of serious illness that might be cancer]. Second ed 2012, Copenhagen, Denmark.

- Weller D, Vedsted P, Rubin G, et al. The Aarhus statement: improving design and reporting of studies on early cancer diagnosis. Br J Cancer. 2012;106:1262–1267.

- Naeser E, Fredberg U, Møller H, et al. Clinical characteristics and risk of serious disease in patients referred to a diagnostic centre: A cohort study. Cancer Epidemiol. 2017;50:158–165.

- Donker GA, Wiersma E, van der Hoek L, et al. Determinants of general practitioner's cancer-related gut feelings-a prospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e012511.

- Holtedahl K, Vedsted P, Borgquist L, et al. Abdominal symptoms in general practice: Frequency, cancer suspicions raised, and actions taken by GPs in six European countries. Cohort study with prospective registration of cancer. Heliyon 2017;3:e00328.

- Ewing M, Naredi P, Nemes S, et al. Increased consultation frequency in primary care, a risk marker for cancer: a case-control study. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2016;34:205–212.

- Hansen PL, Hjertholm P, Vedsted P. Increased diagnostic activity in general practice during the year preceding colorectal cancer diagnosis. Int J Cancer. 2015;137:615–624.

- Naeser E, Møller H, Fredberg U, et al. Routine blood tests and probability of cancer in patients referred with non-specific serious symptoms: a cohort study. BMC Cancer. 2017;17:817.