I began my carrier in cancer research in March 1973, working as a PhD student in tumour biology at the Department of Pathology, Uppsala University. To become a specialist in clinical pathology, one must work in other disciplines and clinical oncology seemed a natural choice; this I did in 1978. After having spent a post-doctoral year in the US, my interest in working with patients exceeded my interest in diagnostic pathology. Subsequently, I have worked as a clinical oncologist and experienced a fantastic development in most aspects of oncology.

I cannot remember when I was first asked to review a manuscript submitted to Acta Oncologica, but I recall being requested to review manuscripts several times in the early 1990s. Possibly because of positive responses and the fact that I had published articles in the journal, I was in the spring 1994 asked by the new editor-in-chief Jerzy Einhorn to become an editor. I felt greatly honoured by this request and have since then with great pleasure and interest worked for Acta, first as editor and, after Jerzy’s demise in April 2000, as editor-in-chief.

Jerzy Einhorn’s predecessor, Lars-Gunnar Larsson, wrote in 1994 an editorial entitled ‘50 years in oncology’, describing the remarkable development that he had observed in oncology during his career [Citation1]. Inspired by his editorial, I decided to provide some reflections from my 45 years in oncology. We can both describe a ‘remarkable progress for oncologists of our generations’.

Having come from an experimental, tumour-biological milieu, I was inspired by the pronounced progress in cell- and tumour biology. The future entailed applying basic knowledge to individualize therapy and, as was so often said in those days ‘within 25 years, cancer will become a chronic disease with which patients can live without risking a premature death’. Systemic treatments will take over. Surgery cannot improve survival any further. Radiotherapy will diminish in importance and newer drugs will prevent tumour growth in most patients. Immunotherapy was promising, particularly after articles and presentations in the first half of the 1970s by the Swedish couple Karl-Erik and Ingegärd Hellström, who were working in Seattle, US. Reality turned out to be different, and most of the expectations turned out to be either erroneous or delayed.

Improvements in the care of cancer patients observed during the past 45 years

Surgery has continued to improve

Despite emphatic statements that the principles of tumour surgery had been established prior to the late 1970s, further improvements have in fact taken place. One of these improvements is dissection in anatomical or embryological planes, achieving higher cure rates because of lower risks of lethal and often severely debilitating loco-regional recurrences (in rectal cancer from about 40% to approximately 4%) [Citation2,Citation3]. The surgical treatment of liver metastases, or onco-surgery, has literally exploded in frequency; in an investigation from the 1990s, only about 4% of the patients with liver metastases only from colorectal cancer were radically operated in Stockholm [Citation4] compared with 18% in Sweden 10–15 years later [Citation5]. The increased use of radiotherapy and improved systemic therapies have contributed to this development. During the past decade, open surgery practised for over a century has, in many instances, been replaced by minimally invasive surgery, including robotic surgery, which have not led to higher cure rates but to reductions in surgical trauma. The use of endoscopic procedures for diagnosis and therapy and improved possibilities for thermal ablation have also contributed to improved treatment results.

Radiotherapy is more vital than ever

When I began working with radiotherapy, computer-based treatment planning had been around for a few years, greatly facilitating the entire radiation therapy work flow. Planning was then only possible in two dimensions and it was claimed that planning in three dimensions would never be practically possible. The enormous development in computer science has made advanced dose planning possible in multiple dimensions (some even talk of 4 and 5 dimensions) with regular personal computers. This planning results in lower radiation doses to surrounding non-tumour containing volumes and in the possibility of increasing the radiation dose to volumes populated by tumour cells, i.e., higher cure rates with reduced morbidity. Radiotherapy today is entirely different from what it was some decades ago and this is not always recognized. Our knowledge about the late effects caused by radiation stems from out-dated techniques. Much of the progress in radiation oncology, including our understanding of the biological effects of radiation, have first been described or reviewed in articles in Acta Oncologica [Citation6–12]. Despite many attempts, the possibilities of predicting response of an individual tumour to radiation, administered alone or in combination with a drug, are very limited. We must continue to live with a great heterogeneity in both tumour response and in the risk of late adverse effects.

Few of the technical developments in loco-regional therapies have been subject to randomised trials, thus formally providing less scientific evidence than is the case with medical oncology. Nevertheless, several therapies have proven to result in long-term survival advantages, although the magnitude of gain of one modality over the other is not precisely known.

Systemic therapies have exploded

While the possibilities of loco-regional tumour control have improved, overall survival has not done so to the same extent, because most deaths are caused by distant metastases. At the end of the 1970s, few malignancies were sensitive to treatment with cytotoxic drugs and thus, most patients treated at an oncology department received radiation therapy. With the introduction of newer cytotoxic drugs often used in different combinations, and by coming to an understanding that the limited cell-kill effect of the drugs/drug combinations was best used as adjuvant therapy after surgery, many more patients have been cured. Whether incurable patients have lived a better life thanks to chemotherapy was rudimentarily known up until in the mid-1990s, when quality-of-life data started to appear. The development in efficacy and use of systemic therapies during subsequent decades, initially hormones/antihormones and ‘conventional cytostatics’ but, since the early years of this decade also ‘targeted agents’ has been enormous. Their use has markedly increased, but, unfortunately, not always their efficacy. Just as with the effects of radiation, the response varies extensively between tumour types but also between individuals with the same tumour type. Many gains have been very limited, or incremental, in the population and with increasing economic costs for recently developed drugs, an often-extensive use was questioned, and examinations such as that by the Swedish Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Assessment of Social Services (SBU) initiated [Citation13]. Many gains were marked and thus became part of routine care whereas others were ‘incremental’ and not recommended for use even if proven active in randomised trials. In the SBU report, chemotherapy was considered to be used both too much but also too little.

Since the SBU report, targeted drugs have appeared, and some have improved response rates quite dramatically, such as imatinib for chronic myeloid leukaemia (in my view the most dramatic gain) and gastrointestinal stroma tumours and rituximab for B-cell lymphomas, others with once again incremental effects unless the tumours could be molecularly selected. Although claimed to be less toxic than ‘dirty cytostatics’, they were not always so, although their toxicity patterns differ considerably. During the past few years, an explosion in new drugs, specific for molecular alterations has occurred, markedly improving at least response rates for many individuals. Previously difficult-to-treat tumours such as non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC), kidney cancer and malignant melanoma can occasionally be very sensitive to these more recent targeted drugs. Pancreatic cancer and malignant glioma remain insensitive – although some are beginning to see some light in the tunnel.

Immunotherapy has finally proven efficacious

Ever since I began teaching in oncology at the end of the 1970s, questions about whether strengthening the immune system would prove a better way of treating cancer than administering toxic therapies have arisen. As I mentioned above, immunotherapy was a promising approach already in the early 1970s, with claims of a breakthrough occurring within 10–15 years. As time has passed, I may have been bantering in response to such questions, stating that it has been promising for 10, or 20, or even 30 years and that it is still ‘only’ promising. I admire all researchers within the field of immunotherapy who have learned so much more about how the immune system may influence tumour cell development and growth. It was a great moment when I could modify my response some 6–7 years ago; immunotherapy is no longer only promising, it will be yet another active treatment modality helping many patients. This was chiefly based upon the discovery of two surface molecules on T-cells, discovered during the first half of the 1990s by this year’s (2018) Nobel prize winners in physiology or medicine, Tasuku Honjo detecting PD-1 [Citation14] and James Allison detecting CTLA-4 [Citation15] a few years later.

No checkpoint inhibitor has yet been approved for clinical use in Sweden in the tumour types I mainly worked with before retirement, so I shall not get personal experience of the efficacy and toxicity of these treatments, which I feel sad about. I notice with gratitude the gains achieved in the treatment of malignant melanoma and NSCLC. Even if this is a breakthrough, most tumours are still in an ‘immunological desert’, since they do not respond.

Has development been rapid?

The development that has taken place reminds me of ‘the law of π’. Whenever a researcher says that an invention, or a new promising compound will become practically available and useful within x number of years, one should multiply x with π (3.14) to obtain a more realistic idea of the time span involved. That law fits well with the development in immunotherapy and in other areas of oncology. Progress has not always been rapid, at least not in the transition from basic tumour biological knowledge to clinical application. It has been claimed that the ‘cancer question’ was solved over a decade ago, and this may be true in the sense that cancer is a disease in the genes, although, in practice, it is not solved. The prediction of ‘cancer being a chronic disease within 25 years’ made when I left basic science and clinical pathology for patient work, is not yet true. I question whether I in my lifetime can state that it will be true such as is the case for diabetes and heart failure, even if one can hear this from enthusiastic colleagues.

Supportive and palliative care

Progress has not only been observed in anti-tumour treatments. Progress has also taken place in supportive care, further improving the situation for cancer patients and their relatives and friends. The introduction of better anti-emetics, particularly the 5HT3-receptorantagonists in the early 1990s markedly facilitated the delivery of anticancer treatments. The recognition of palliative care, which was pioneered in the UK during the end of the 1960s and the development in palliative medicine as a discipline and research area 20 years later have similarly changed the prospect of many individuals to the better. Psychosocial oncology, cancer rehabilitation and other aspects of cancer survivorship have been in focus more recently as fundamental aspects of total care, again with Acta Oncologica as an important player.

Personalized medicine

This expression has been a keyword for decades, being the topic at large conferences and research schools and expressed in numerous presentations. On the one hand, all activities in medicine must be personalized. On the other hand, few activities in oncology are today personalized in the way most of us understand by these words. Treatments are still mainly administered to populations. Huge progress has been seen in our understanding of tumour biology, but the level of detail is still too superficial to fill the expression ‘personalized medicine’ with a relevant content.

Evidence-based medicine

Although randomised clinical trials had been used previously, it was not until Peto et al. described the design and analyses of such trials [Citation16,Citation17], articles which I and probably many with me repeatedly studied, that the knowledge base of outcomes in medicine, including oncology, became established. Further refinements including how to perform systematic overviews and meta-analyses of available evidence have also contributed greatly. Also, minor gains, sometimes clinically valuable, sometimes unfortunately not, could be firmly established. Further developments of descriptive and analytical epidemiological techniques have greatly facilitated our knowledge in many important aspects, such as the detection and analysis of risk factors for cancer and the understanding of the importance of different interventions for outcomes. Large population-based databases, and the creation of national quality registers and biobanks during the past decades have likewise been indispensable for progress. Without the registers we could for example not know whether the advantages seen in trials also translate into progress in populations. Unfortunately, several trials have selected the patients so extensively that the population gains are not nearly the same, and sometimes not even detectable. More pragmatic trials are needed. Without the population registries, we would also not know much about late effects caused by different therapies, or expressed in a different way, the ‘consequences of success’.

Anything getting worse?

As I mentioned above, when I began to work in oncology, most patients received radiotherapy. At the same time, the number of hospital beds was much greater than today, and it was not uncommon for patients living far away from the hospital to stay in hospital during the entire radiation course of 6–7 weeks. In retrospect, this was a huge waste of resources and money. The situation today is the opposite, much fewer beds and much more to do; there are limited possibilities for inpatient care even for those in great need and the median hospital stay is one or two days. The pendulum has swung too far in the opposite direction.

Improvements for Acta Oncologica during the past 25 years

Acta Oncologica is a general oncology journal with the ambition of publishing articles in all aspects of oncology. It is the scientific periodical of the Nordic societies of oncology and the Nordic Association of Clinical Physics (NACP). The journal is not a high-impact journal where the newest results are first published. However, the content over the decades provides a good reflection of the progress seen and briefly outlined above. In areas such as radiation oncology, supportive care and cancer survivorship, epidemiology and outcome research, Acta Oncologica attracts first-class articles, mainly since there exist strong scientific possibilities for and interest in these research areas in the Nordic countries.

Since 2000, Acta Oncologica has supported 17 symposia dealing with different topics. All symposia have resulted in the publication of reviews and original articles in a regular issue of the journal. Two topics have been repeated every other year during the past 10 years, one about advanced radiation therapy (Biology-Guided Adaptive Radiotherapy, BIGART) and the other about cancer rehabilitation and survivorship (European Cancer Rehabilitation and Survivorship Symposium, ECRS) [Citation18,Citation19]. Every third year, support has been given to NACP meetings, again with several articles in the journal. The marriage between Acta and NACP continues to be, as anticipated, happy [Citation20].

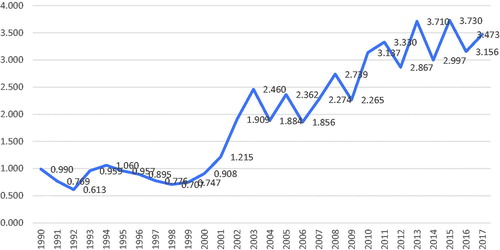

During my almost two decades as chief editor, I have in editorials described the progress of Acta Oncologica, attracting more and more articles (from initially about 200 to presently about 1000) and, today considered to be of greatest relevance, more citations () [Citation21,Citation22]. The title of my first editorial was similar to one of the last ones [Citation21], based upon a recommendation given during a course for scientific editors in 2001, ‘Tell all good news as soon as possible’. The number of issues every year has increased from 8 to 12, allowing more articles to be accepted and published, or from about 100 per year to, most recently, 270. Of spontaneously submitted articles, the rejection rate is almost 80%. The far majority of submitted manuscripts are handled within 30 days but, unfortunately, the review process takes too long time for some manuscripts. It has been claimed that invited referees today are more reluctant to accept an invitation and provide an adequate response within a few weeks than in the past. Based upon a correspondence between the editors 25 years ago, the same opinions were then expressed. Unfortunately, not all scientists give priority to matters they expect others to.

In 2013, Acta Oncologica celebrated its 50th anniversary after its separation from Acta Radiologica [Citation23,Citation24]. The present name was adopted in 1987. In between, different names were used illustrating a long separation process (Acta Radiologica: Therapy, Physics, Biology (1963–1977); Acta Radiologica: Oncology, Radiation, Physics, Biology (1978–1979); Acta Radiologica: Oncology (1980–1986)). Several successful activities took place during 2013, among them the Young Scientist Workshop. About 20 young scientists from the Nordic countries learned how to perform systematic reviews [Citation25] and four such reviews were later published [Citation12,Citation26–28].

During the years, I have also written editorials within my own field of interest, gastrointestinal oncology, most recently [Citation29–32]. I hope it has not been easier for me to see strengths in manuscripts dealing with gastrointestinal oncology than in other areas of oncology; nor the opposite, i.e., seeing faults in such articles. I have not checked the rejection rates within different research areas. However, innovative research within radiation oncology and cancer survival/supportive care has been more likely to be submitted to Acta than similar articles within e.g., medical oncology. Hopefully Acta Oncologica can also attract such articles in the future.

As an active scientist and editor, I noticed around 1995 the increased interest in bibliometrics. In a letter between my predecessors from 1995, they were pleased by the increase in the ISI impact factor (IF) from 0.613 to 1.060 in two years, but otherwise, they were reluctant to use it in any evaluation of quality. Even if the IF can be criticised in the evaluation of quality of articles, scientists and departments, I realised that it would be ‘foolish of a new editor-in-chief with ambitions for the journal to disregard it’ [Citation33]. My ambition then was that it should increase above 3, which also happened a few years ago (). I am not at all fond of this increased dependence on bibliometrics, where todays choice of where to submit your next article depends of the journal’s IF, but it is impossible to fight. As a chief editor, one must try to maximize the IF within the official and unofficial rules of ethics. The increase in the IF as regards Acta Oncologica from below 1 to above 3 may look impressive, but it should then also be looked at in the light of a markedly increased publishing of articles in all areas, including oncology. The number of scientific journals has increased markedly. Today, the market is flooded with new open access journals, and the term ‘predatory publishing’ have been introduced [Citation34]. I suspect that many readers of this editorial every day erase from their emails many invitations to submit ‘whatever you want’ to a new journal. I do. Recently, new algorithms, e.g., the altmetric attention score have also been developed to evaluate the importance of the articles published in a journal. I have so far been sceptic to this, but my successor must probably consider them more seriously.

As editor of a scientific journal, one is part of a long tradition aimed at distributing knowledge based upon scientific activities and put together by authors in a recognized format, being scrutinized by external reviewers selected for their knowledge within the field and finally evaluated by an editor and the editor-in-chief. Many articles have passed through several rounds of reviewing before having sufficient quality for acceptance. If properly handled, this peer-review process is a requirement for quality in what is published, although it, by no means, is a guarantee that poor science, including falsification, turns up in published form. There is, at least presently, no better way of securing a high standard of quality in what scientists can read in periodicals. I am thankful for having had the confidence from the Acta Oncologica foundation, but ultimately from all oncological scientists in the Nordic countries to act as chief editor of their periodical. I am also thankful for all authors who have submitted their work to Acta for evaluation, all editors who have helped in the review process and, above all, all invited reviewers providing constructive criticism. Today most authors submitting their article to Acta receive a disappointing rejection letter. Previously, most decision letters contained detailed comments on how to improve the article so that it might become acceptable for publication. It has been an honour to be a part of this process and it has, at the same time, been extremely educational and rewarding. I am convinced that the reviewing process has also been educational for authors, even if their work was not always accepted.

It is my belief that this scholarly scientific process will continue in Acta Oncologica, and in other ‘traditional’ journals. I sincerely hope that the distribution of scientific information will strive towards similar standards of quality. The substantial increase in the number of manuscripts submitted without a similar increase in the number of scientists, the easiness with which articles are submitted to journals and the multitude of predatory open-access journals, many accepting articles (for money) without proper external reviewing are dark clouds in the information sky. Many traditional journals, often together with their societies, have also created open access journals ‘downstream’ of the main journal, publishing articles of sufficient quality motivating their distribution to readers, albeit not sufficient for publication in the main journal. This was also extensively discussed among the editors and by the board representing the Nordic associations in Acta Oncologica for several years, although the decision about a year ago was to temporarily stop the process.

To get a journal to run smoothly, one also needs a dedicated staff of managing editors who facilitate the process internally and with the publisher. I am very thankful for the extremely skilful help I have received from the team, during recent years Lena Andreasson-Haddad and Marielle Pellas. The interaction with the publishers has always run smoothly.

After just over 18 years as chief editor, it is time for me to hand over the reins to a new generation. The successor, professor Mef Nilbert has been part of the editorial board for many years and her critical and skilful way of acting in that position gives me confidence that Acta Oncologica will further develop as an important transmitter of scientific knowledge within oncology with its base in the Nordic countries. Together with the other members of the editorial board, some very experienced, some more recently appointed, she will continue to value truth and quality. I wish Mef and Acta Oncologica a successful future. It is my hope that when she retire, the expression ‘personalized medicine’ can be filled with a relevant content for most patients with a malignancy.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

References

- Larsson LG. 50 years with oncology. Acta Oncol. 1994;33:847.

- Påhlman L, Glimelius B. Local recurrences after surgical treatment for rectal carcinoma. Acta Chir Scand. 1984;150:331–335.

- Glimelius B, Myklebust TÅ, Lundqvist K, et al. Two countries – two treatment strategies for rectal cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2016;121:357–363.

- Sjovall A, Jarv V, Blomqvist L, et al. The potential for improved outcome in patients with hepatic metastases from colon cancer: a population-based study. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2004;30:834–841.

- Noren A, Eriksson HG, Olsson LI. Selection for surgery and survival of synchronous colorectal liver metastases; a nationwide study. Eur J Cancer. 2016;53:105–114.

- Brahme A. Design principles and clinical possibilities with a new generation of radiation therapy equipment. A review. Acta Oncol. 1987;26:403–412.

- Withers HR, Taylor JMG, Maciejewski B. The hazard of accelerated tumor clonogen repopulation during radiotherapy. Acta Oncol. 1988;27:131–146.

- Brahme A. Biologically based treatment planning. Acta Oncol. 1999;38 Suppl.13:61–68.

- Lax I, Blomgren H, Naslund I, et al. Stereotactic radiotherapy of malignancies in the abdomen. Methodological aspects. Acta Oncol. 1994;33:677–683.

- Denekamp J, Fowler JF. ARCON-current status: summary of a workshop on preclinical and clinical studies. Acta Oncol. 1997;36:517–525.

- Tubiana M, Eschwege F. Conformal radiotherapy and intensity-modulated radiotherapy–clinical data. Acta Oncol. 2000;39:555–567.

- Thornqvist S, Hysing LB, Tuomikoski L, et al. Adaptive radiotherapy strategies for pelvic tumors – a systematic review of clinical implementations. Acta Oncol. 2016;55:943–958.

- Glimelius B, Bergh J, Brandt L, et al. The Swedish Council on Technology Assessment in Health Care (SBU) systematic overview of chemotherapy effects in some major tumour types – summary and conclusions. Acta Oncol. 2001;40:135–154.

- Ishida Y, Agata Y, Shibahara K, et al. Induced expression of PD-1, a novel member of the immunoglobulin gene superfamily, upon programmed cell death. EMBO J. 1992;11:3887–3895.

- Krummel MF, Allison JP. CD28 and CTLA-4 have opposing effects on the response of T cells to stimulation. J Exp Med. 1995;182:459–465.

- Peto R, Pike MC, Armitage P, et al. Design and analysis of randomized clinical trials requiring prolonged observation of each patient. I. Introduction and design. Br J Cancer. 1976;34:585–612.

- Peto R, Pike MC, Armitage P, et al. Design and analysis of randomized clinical trials requiring prolonged observation of each patient. II. Analysis and examples. Br J Cancer. 1977;35:1–39.

- Grau C, Hoyer M, Poulsen PR, et al. Rethink radiotherapy – BIGART 2017. Acta Oncol. 2017;56:1341–1352.

- Johansen C, Dalton SO. Survivorship in new harbors. Acta Oncol. 2017;56:119–122.

- Muren LP, Glimelius B. And they lived happily ever after… The marriage of Nordic Association for Clinical Physics and Acta Oncologica. Acta Oncol. 2011;50:835–837.

- Glimelius B. Tell all the good news as soon as possible. Acta Oncol. 2016;55:1067–1068.

- Glimelius B. More than 1000 new manuscripts in 2017. Acta Oncol. 2018;57:174–175.

- Glimelius B. The 50-year anniversary of Acta Oncologica. Acta Oncol. 2014;53:1–2.

- Glimelius B. 50 years with Acta Oncologica. Acta Oncol. 2013;52:1–2.

- Glimelius B, Johansen C, Muren LP, et al. Acta Oncologica and a new generation of scientists in oncology. Acta Oncol. 2014;53:849–851.

- Bockelman C, Engelmann BE, Kaprio T, et al. Risk of recurrence in patients with colon cancer stage II and III: a systematic review and meta-analysis of recent literature. Acta Oncol. 2015;54:5–16.

- Poulsen LO, Qvortrup C, Pfeiffer P, et al. Review on adjuvant chemotherapy for rectal cancer – why do treatment guidelines differ so much? Acta Oncol. 2015;54:437–446.

- Therkildsen C, Bergmann TK, Henrichsen-Schnack T, et al. The predictive value of KRAS, NRAS, BRAF, PIK3CA and PTEN for anti-EGFR treatment in metastatic colorectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Oncol. 2014;53:852–864.

- Glimelius B. Any progress in pancreatic cancer? Acta Oncol. 2016;55:255–258.

- Glimelius B. What is most relevant in preoperative rectal cancer chemoradiotherapy – the chemotherapy, the radiation dose or the timing to surgery? Acta Oncol. 2016;55:1381–1385.

- Glimelius B, Martling A. What conclusions can be drawn from the Stockholm III rectal cancer trial in the era of watch and wait? Acta Oncol. 2017;56:1139–1142.

- Bockelman C, Glimelius B. Need for adjuvant chemotherapy after colon cancer surgery – has it decreased? Acta Oncol. 2017;56:629–633.

- Glimelius B. Oncology in the Nordic countries—the role of Acta Oncologica? Acta Oncol. 2002;41:3–5.

- Shen C, Bjork BC. ‘Predatory’ open access: a longitudinal study of article volumes and market characteristics. BMC Med. 2015;13:230