Abstract

Background: Neoadjuvant chemoradiation with delayed surgery (CRT-DS) and short-course radiotherapy with immediate surgery (SCRT-IS) are two commonly used treatment strategies for rectal cancer. However, the optimal treatment strategy for patients with intermediate-risk rectal cancer remains a discussion. This study compares quality of life (QOL) between SCRT-IS and CRT-DS from diagnosis until 24 months after treatment.

Methods: In a prospective colorectal cancer cohort, rectal cancer patients with clinical stage T2-3N0-2M0 undergoing SCRT-IS or CRT-DS between 2013 and 2017 were identified. QOL was assessed using EORTC-C30 and EORTC-CR29 questionnaires before the start of neoadjuvant treatment (baseline) and at 3, 6, 12, 18 and 24 months after. Patients were 1:1 matched using propensity sore matching. Between- and within-group differences in QOL domains were analyzed with linear mixed-effects models. Symptoms and sexual interest at 12 and 24 months were compared using logistic regression models.

Results: 156 of 225 patients (69%) remained after matching. The CRT-DS group reported poorer emotional functioning at 3, 6, 12, 18 and 24 months (mean difference with SCRT-IS: −9.4, −12.1, −7.3, −8.0 and −7.9 respectively), and poorer global health, physical-, role-, social- and cognitive functioning at 6 months (mean difference with SCRT-IS: −9.1, −9.8, −14.0, −9.2 and −12.6, respectively). Besides emotional functioning, all QOL domains were comparable at 12, 18 and 24 months. Within-group changes showed a significant improvement of emotional functioning after baseline in the SCRT-IS group, whereas only a minor improvement was observed in the CRT-DS group. Symptoms and sexual interest in male patients at 12 and 24 months were comparable between the groups.

Conclusions: In rectal cancer patients, CRT-DS may induce a stronger decline in short-term QOL than SCRT-IS. From 12 months onwards, QOL domains, symptoms and sexual interest in male patients were comparable between the groups. However, emotional functioning remained higher after SCRT-IS than after CRT-DS.

Introduction

Neoadjuvant therapy followed by surgery is the cornerstone of treatment in most patients with rectal cancer [Citation1]. According to the Dutch rectal cancer guideline, patients with high-risk, locally advanced rectal cancer (including irresectable tumors, four or more suspicious regional lymph node metastases and/or suspicious extramesorectal lymph nodes) undergo chemoradiation – 45–50 Gy in fractions of 1.8–2 Gy in 5 weeks with concurrent chemotherapy – followed by delayed surgery (CRT-DS) usually after 8–12 weeks [Citation2]. CRT-DS was designed to downsize high-risk rectal tumors and so to achieve curative resection and to decrease the risk of local recurrence [Citation3–5]. Patients with intermediate-risk, resectable rectal cancer, receive short-course radiotherapy – 25 Gy in 5 fractions – followed by immediate surgery (SCRT-IS) usually within 10 days after the start of radiotherapy. SCRT-IS has shown to improve local control as well as cancer-specific survival in patients with negative resection margins compared to surgery alone [Citation6,Citation7]. However, the optimal treatment strategy for intermediate-risk rectal cancer remains a discussion [Citation8], partly because organ-sparing treatment options are not feasible in patients undergoing SCRT-IS in constrast to patients with a clinical complete response (cCR) following CRT [Citation9].

Literature on SCRT-IS versus CRT-DS showed comparable survival, local and distant recurrence rates, sphincter preservation rate, radical resection rate and late toxicity in patients with various disease stages [Citation10,Citation11]. Nonetheless, a higher rate of acute toxicity after CRT-DS was observed in a Polish randomized trial including patients with a cT3-4 rectal tumor (18% versus 3% after SCRT-IS) [Citation12]. Postoperative complications, however, did not differ significantly between the groups [Citation13]. The Stockholm III trial, in which patients with resectable rectal cancer were randomized between SCRT-IS, SCRT with delayed surgery and long-course radiotherapy with delayed surgery (without concurrent chemotherapy), showed a higher, although non-significant, postoperative complication rate in the SCRT-IS group (50% versus 39% in the long-course radiotherapy group versus 38% in the SCRT with delayed group) and comparable oncological outcomes [Citation14].

Nevertheless, CRT-DS involves a more extensive treatment including chemotherapy and a longer treatment duration than SCRT-IS. On the other hand, CRT may give the opportunity to opt for organ-sparing treatment approaches in case of a cCR [Citation9,Citation15,Citation16], which would be suitable in approximately 15–20% of the LARC patients (based on pathological complete response rates) [Citation17]. Patients undergoing SCRT-IS do not have the chance to achieve cCR and to proceed to organ-preservation because of the short time interval between neoadjuvant therapy and resection. Replacement of SCRT-IS by CRT-DS in patients with intermediate-risk rectal cancer may render patients with a complete response to become eligible for organ-sparing treatment. However, this may have implications for patients’ health-related quality of life (QOL) during and after rectal cancer treatment.

Literature on the effect of SCRT-IS versus CRT-DS on patients’ QOL during treatment is scarce [Citation18]. A randomized trial from Australia compared SCRT with CRT up to 12 months after surgery and observed no differences [Citation18]. Nevertheless, in this study, the longer treatment duration of CRT-DS was not considered because date of surgery was set as baseline. Based on our previous observational study on QOL during rectal cancer treatment, we noticed worse QOL in patients undergoing CRT-DS compared with SCRT-IS at 6 and 12 months after the start of treatment [Citation19]. However, these findings were based on univariable analyses. In the present study, we, therefore, aimed to compare QOL between SCRT-IS and CRT-DS from start of treatment until 24 months after in a cohort using propensity score matching.

Material and methods

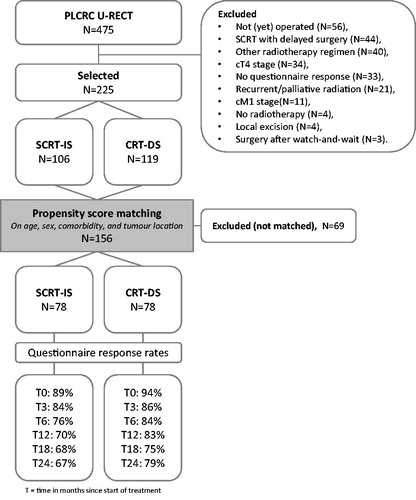

The Dutch Prospective Data Collection Initiative on Colorectal Cancer (PLCRC) cohort includes adult patients with colorectal cancer and has been approved by the Medical Research Ethics Committee of the University Medical Centre (UMC) Utrecht, the Netherlands [Citation20]. Within PLCRC, participants gave informed consent to the collection of clinical outcomes and optionally consented to questionnaires on patient reported outcomes (PROs). For the present study, we selected PLCRC participants of the Utrecht RECTal cancer (U-RECT) sub cohort, that includes patients referred for radiotherapy of rectal cancer to the Radiation-Oncology Department of the UMC Utrecht. We included patients with a cT2-3N0-2M0 enrolled between February 2013 and August 2017, who underwent routine SCRT-IS or CRT-DS with curative intent, who gave informed consent for PROs and who responded to at least one questionnaire (). Patients diagnosed with a cT4 stage (N = 34) or with synchronous distant metastases (N = 11) were excluded because these patients may have poorer short-term prognosis which could influence QOL.

Figure 1. Flowchart of selected patients within the prospective data collection initiative on colorectal cancer (PLCRC) Utrecht rectal cancer (U-RECT) cohort treated with short-course radiotherapy with immediate surgery (SCRT-IS) or chemoradiation with delayed surgery (CRT-DS).

All patients were treated in accordance with the Dutch guideline and underwent intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT) [Citation2]. CRT is delivered to patients with LARC (cT4 or cT3 with a distance to the mesorectal fascia (MRF) of ≤1 mm, and/or cN2 and/or suspicious extramesorectal lymph node metastases) and consists of 25 × 2 Gy with concurrent oral Capecitabine (825 mg/m2 twice a day) followed by delayed surgery. SCRT is administered in patients with intermediate-risk disease (cT3c-dN0 or cT1-3N1 with a distance to the MRF of >1 mm, and cT2-3N0 before the implementation of the current guideline in 2014) and consists of 5 × 5Gy followed by immediate surgery. Surgery is performed by the principles of a total mesorectal excision (TME), including low anterior resection (LAR) with or without temporary deviating stoma, abdominoperineal resection (APR) with permanent colostomy or rectosigmoid resection with permanent colostomy (Hartmann’s procedure). Adjuvant therapy is not routinely administered.

QOL was assessed using the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) core QOL questionnaire (QLQ-C30) [Citation21] and colorectal-specific questionnaire (QLQ-CR29) [Citation22] before the start of neoadjuvant treatment (baseline) and at 3, 6, 12, 18 and 24 months after. The EORTC QLQ-C30 consists of 5 functioning domains (physical, role, emotional, cognitive and social functioning), a global health score and cancer-related symptoms [Citation21]. The EORTC QLQ-CR29 comprises colorectal cancer-specific scales and symptoms [Citation22]. For this study, we presented prevalent rectal cancer treatment-related symptoms [Citation19] including fatigue, insomnia and pain of the EORTC QLQ-C30 and bowel-related items (stool frequency, flatulence and fecal incontinence) and genitourinary-related items (urinary frequency, urine incontinence, impotence and sexual interest) of the EORT QLQ-CR29. Questionnaires were provided online or on paper and collected within the Patient Reported Outcomes Following Initial treatment and Long-term Evaluation of Survivorship (PROFILES) registry [Citation23]. Patient and treatment characteristics were collected from patients’ medical files.

Statistics

To decrease the risk of confounding bias in this observational study, patients in the SCRT-IS and CRT-DS group were matched using propensity score matching (PSM). PSM is a statistical matching technique using the probability of treatment assignment conditional on observed covariates [Citation24]. Propensity scores were estimated by logistic regression, with treatment strategy group (CRT-DS versus SCRT-IS) as dependent variable and age (continuous), sex, presence of at least one comorbidity, and tumor location as independent variables. Matching was performed according to the ‘nearest neighbour’ method using a caliper width of 0.55 times the standard deviation of the logit of the propensity score and 1:1 ratio. Patients were not matched on cT-stage, cN-stage, and MRF involvement as these variables are used as selection criteria for SCRT-IS and CRT-DS. Baseline characteristics were described before and after matching with use of summary statistics.

QOL outcomes were handled according to the EORTC manual and linearly transformed into scores between 0 and 100 [Citation25]. Higher scores indicate better functioning, better global health, and higher symptom severity. To compare between-group differences in QOL domains of the EORTC QLQ-C30 at the different time points, linear mixed-effects models were used to take into account the intra-subject correlation between the repeated measurements and included a random intercept, time (as factor), treatment strategy group, adjusted for baseline QOL score and surgical procedure (LAR without stoma, LAR with temporary stoma, Hartmann’s procedure and APR) with an autoregressive covariance structure of the first order (AR1) assuming that the correlation systematically decreases with increasing distance between time points [Citation26]. The outcomes were presented as mean differences (MD) with the 95% confidence intervals (CI). Standardized effect sizes (ES) were calculated by dividing the MD by the pooled standard deviation of the baseline score and were categorized into no (ES <0.2), small (ES =0.2–0.4), moderate (ES =0.5–0.7), and large difference (ES >0.7), according to Cohen [Citation27]. Within-group differences were obtained with linear mixed-effects models including the baseline measurement as outcome variable and stratified by treatment strategy group, presenting the change in QOL relative to baseline for the treatment groups apart. Symptoms were categorized into none (score =0), mild (score =1–49), moderate (score =50–99) and severe complaints (score =100), corresponding to the original 4-point Likert scale answer options (for sexual interest these categories were ‘not at all’, ‘a little’, ‘quite a bit’ and ‘very much’, respectively). The effect of treatment strategy on symptoms (moderate/severe versus none/mild) and sexual interest (no versus yes) was estimated using univariable logistic regression models. As we were primarily interested in differences in late toxicity between the groups, we formally tested for differences only at 12 and 24 months after the start of treatment. The outcomes were presented as odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals. Significance level was set at p < 0.05. Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 23 was used and ‘MatchIt’ and ‘opmatch’ packages in R version 3.4.1.

Results

Of the 225 patients whom met the inclusion criteria, 106 (47.1%) patients underwent SCRT-IS and 119 (52.9%) CRT-DS (). The CRT-DS group included younger patients with lower rectal tumors, higher cT-stages, higher cN-stages, more MRF involvement, and more APR procedures compared to the SCRT-IS group (). After matching, 156 (61.2%) patients remained (78 patients in each group). Patients in the CRT-DS and SCRT-IS group were well balanced in terms of the matched variables and surgical procedure (). As expected, more patients in the CRT-DS group were diagnosed with a cT3 stage (96.2% versus 64.1% in the SCRT-IS group), positive suspected lymph nodes (cN1 or cN2: 94.9% versus 75.6% in the SCRT-IS group), and distance to the MRF of ≤1 mm (65.4% versus 1.3% in the SCRT-IS group). Also, more patients in the CRT-DS group received a LAR with deviating stoma than in the SCRT-IS group (44.9% versus 34.6%). Median delay from completion of neoadjuvant treatment to surgery was 3 days in the SCRT-IS group and 76 days (10 weeks) in the CRT-DS group. Median follow-up time and median year of treatment in the SCRT-IS group was 32 months and 2015 respectively, and in the CRT-DS group 40 months and 2014 respectively.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics before and after propensity score matching of rectal cancer patients treated with neoadjuvant short-course radiotherapy with immediate surgery (SCRT-IS) or neoadjuvant chemoradiation with delayed surgery (CRT-DS).

Questionnaire response rates at baseline, 3, 6, 12, 18 and 24 months, accounted for follow-up time and mortality, in the SCRT-IS group were 69/78 (89%), 65/78 (84%), 58/76 (76%), 49/70 (70%), 44/65 (68%) and 35/52 (67%) respectively and in the CRT-DS group 73/78 (94%), 66/77 (86%), 64/76 (84%), 60/72 (83%), 51/68 (75%) and 48/61 (79%) respectively. The number of responses for all individual items are presented in Supplementary Data .

Between-group differences in QOL

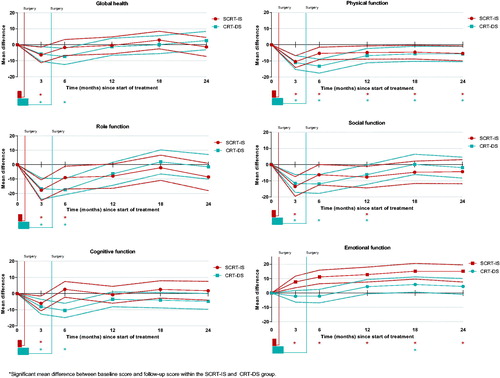

Compared with the SCRT-IS group, patients in the CRT-DS group reported significantly poorer emotional functioning at 3 and 6 months with moderate ES (MDs −9.4 and −12.1, respectively) and at 12, 18, and 24 months with small ES (MDs −7.3, −8.0 and −7.9, respectively) (). At 6 months, global health, physical-, role-, and cognitive functioning were significantly poorer in the CRT-DS group than in the SCRT-IS group with moderate ES (MDs −8.9, −9.9, −13.6 and −12.3, respectively) and social functioning was poorer with a small ES (MD −9.2). Besides emotional functioning, all functioning scores were comparable between the groups at 12, 18 and 24 months after the start of treatment.

Table 2. Differences in quality of life domains of the EORTC QLQ-C30 questionnaire between neoadjuvant short-course radiotherapy with immediate surgery (SCRT-IS) and neoadjuvant chemoradiation with delayed surgery (CRT-DS) in a matched cohort of rectal cancer patients.

Within-group differences in QOL

Within-group differences show the changes in QOL relative to baseline stratified by treatment strategy group (). At 3 months, a significant decline was observed in all QOL domains, but emotional functioning, compared with baseline level in both treatment groups. In the SCRT-IS group, global health and cognitive functioning recovered to baseline level after 3 months, and role functioning after 6 months. Social functioning improved after 3 months but remained (borderline) significantly lower than baseline until 12 months. Emotional functioning showed significant improvement at all follow-up measurements. In the CRT-DS group, global health, social-, cognitive- and role functioning returned to baseline level after 6 months. Emotional functioning showed an increasing trend but was only significantly improved since baseline at 18 months. In both groups, physical functioning remained significantly poorer up to 24 months compared with baseline level.

Figure 2. Within-group changes in quality of life domains of the EORTC QLQ-C30 in a matched cohort of rectal cancer patients receiving short-course radiotherapy with immediate surgery (SCRT-IS) or chemoradiation with delayed surgery (CRT-DS). Scores are presented in mean differences with the 95% confidence intervals (dashed lines). Duration of neoadjuvant treatment and approximate timing of surgery are indicated in the boxes below the graphs and the line respectively.

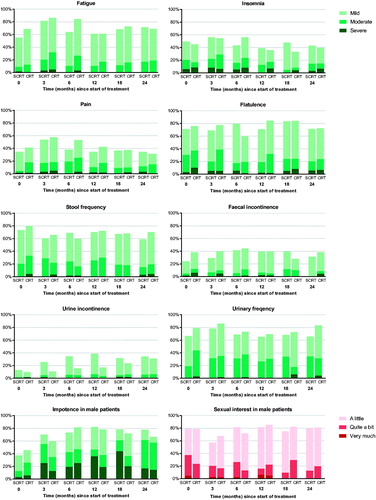

Symptoms and sexual interest

In , longitudinal outcomes for the selected symptoms and for sexual interest in male patients are presented stratified by SCRT-IS and CRT-DS (differences not tested for significance). At 12 and 24 months after the start of treatment, no significant differences in moderate/severe symptoms between the treatment strategy groups were observed (). Also, the probability for having no sexual interest was comparable between SCRT-IS and CRT-DS in male patients at 12 and 24 months after the start of treatment. For female patients, sexual interest was not presented because of the insufficient number of responses.

Figure 3. Categories of symptom severity and sexual interest of the EORTC QLQ-C30 and QLQ-CR29 in the short-course radiotherapy with immediate surgery (SCRT-IS) group and chemoradiation with delayed surgery (CRT-DS) group in a matched cohort of rectal cancer patients. For symptoms, a higher proportion represent more patients with symptoms. For sexual interest, a higher proportion represent more male patients with sexual interest.

Table 3. Results of univariable logistic regression models on the association between treatment strategy and symptoms (moderate/severe versus none/mild) and sexual interest (no versus yes) at 12 and 24 months after the start of treatment in a matched cohort of rectal cancer patients.

Discussion

This study showed that global health, physical-, role-, cognitive- and emotional functioning were poorer in the CRT-DS group than in the SCRT-IS group at 6 months after the start of neoadjuvant treatment with moderate effect sizes. Social functioning at 6 months and emotional functioning at 12, 18 and 24 months were poorer in CRT-DS with small effect sizes. Besides better emotional functioning in the SCRT-IS group, all other QOL domains were comparable with CRT-DS on longer-term. Within-group QOL changes showed that in both groups physical functioning was significantly lower at all follow-up measurements compared with baseline. Symptoms of fatigue, insomnia, pain, stool frequency, flatulence, fecal incontinence, urinary frequency, urine incontinence and impotence as well as sexual interest in male patients were comparable between the groups at 12 and 24 months after the start of treatment.

Several other studies compared QOL between SCRT-IS and CRT-DS [Citation18,Citation28–30]. As mentioned earlier, an Australian trial longitudinally assessed QOL in 297 rectal cancer patients (cT3N0-2M0) randomized between SCRT-IS plus 6 courses of adjuvant chemotherapy and CRT-DS plus 4 courses of chemotherapy at seven time points up to 12 months after randomization [Citation18]. Similar to our findings, a decline in QOL was observed in both treatment groups shortly after surgery with gradually improvement up to 12 months with the most severely affected domains/symptoms including physical- and role functioning, fatigue, pain, impotence and sexual functioning. In contrast to our study, no significant differences in short-term QOL were observed between SCRT-IS and CRT-DS. This could be explained by the re-arrangement of QOL measurements in the Australian study with date of surgery taken as baseline to align treatment duration. However, in our view, the difference in treatment duration is inherent to SCRT-IS and CRT-DS and forms an essential difference between the treatment strategies that, as suggested by our results, may affect QOL. Our aim was therefore to compare the treatment strategies including surgery and not solely radiotherapy regimens. Besides, in contrast to our study, patients in the Australian trial received adjuvant chemotherapy which may likely affect QOL.

A Dutch cross-sectional study compared QOL at a median follow-up of 58 months after diagnosis between 85 patients routinely treated with CRT-DS and 306 patients treated with SCRT-IS in the TME trial [Citation30]. No significant differences were found in global health and functioning. A Polish cross-sectional study neither observed significant differences in QOL and sexual functioning in 222 cT3-4 rectal cancer patients randomized to SCRT-IS or CRT-DS at 12 months after surgery [Citation28]. In a German cross-sectional study with a median follow-up of 67 months after diagnosis, no difference was found in QOL between 108 patients treated with SCRT-IS and 117 patients with CRT-DS, except for better physical functioning in the CRT-DS group [Citation29]. These studies support our conclusion that longer-term QOL is comparable between SCRT-IS and CRT-DS.

As shown by the within-group QOL changes, patients undergoing CRT-DS took longer time to recover to pretreatment levels than patients undergoing SCRT-IS. This could be related to the longer neoadjuvant treatment duration, chemotherapy administration and/or the timing of surgery. Within 24 months, however, all QOL domains have returned to baseline level or above, except for physical functioning which remained lower compared with baseline in both groups. This is in line with a study that investigated recovery of physical functioning after hospital discharge in colorectal cancer patients that showed that half of the patients had not recovered to baseline function at 6 months after diagnosis and that this was more common in rectal cancer patients [Citation31]. This study suggested that an increase in physical activity after surgery is associated with enhanced recovery of physical functioning. More research should focus on improving physical functioning in rectal cancer patients after treatment.

Our findings suggest that emotional functioning is better in patients treated with SCRT-IS than with CRT-DS. Patients in the SCRT-IS group improved to above baseline level, equal to the level of the Dutch normative population (mean score of 89 at 24 months in patients and of 88 in the Dutch population with age of 55–75 years, based on normative population data of PROFILES), which was not the case in the CRT-DS group (mean score of 82 at 24 months). The better emotional functioning in the SCRT-IS group could be related to the shorter treatment duration. Nevertheless, this effect warrants further investigation.

This study has several limitations. First, patients were not randomized to one of the neoadjuvant treatment groups. To minimize the risk of confounding bias, we matched the groups based on their propensity score for treatment conditional on baseline characteristics that may have affected treatment choice. However, this could only be performed for known covariates. Residual confounding can, therefore, not be ruled out. Also, the groups were not matched on clinical disease stage as this was highly correlated with treatment indication. We, therefore, excluded patients with most advanced disease (cT4 and/or M1) and corrected the outcomes on QOL domains for baseline scores, surgical procedure and stoma presence. Besides, the study of the Dutch TME trial, earlier discussed, reported that distance to the MRF, tumor and nodal stage were not associated with QOL in their study population [Citation30]. Also, oncological outcomes, such as recurrence rate, are approximately comparable between resectable and locally advanced rectal cancer patients on the short-term [Citation14,Citation32]. We, therefore, assumed that the differences in disease stage between the groups would not influence QOL during the first 24 months after start of treatment to an important extent. Second, to keep sufficient sample size after matching, the caliper width was set at 0.55 which is wider than recommended in literature [Citation33]. Still, matching was considered successful as the differences in baseline characteristics between the groups were small. Third, the proportion of questionnaire non-responders increased over the time and was slightly higher in the SCRT-IS group, which could have introduced non-response bias of the QOL outcomes, meaning that those who respond to the questionnaire differ from those who do not respond.

Besides the use of CRT to become eligible for organ preservation in intermediate risk rectal cancer patients, SCRT with delayed surgery has been proposed as alternative to SCRT-IS and was investigated by the Stockholm III trial [Citation14] and by a prospective non-randomized study in elderly patients [Citation34]. The Stockholm III trial showed comparable oncological outcomes between SCRT with delayed surgery and SCRT-IS [Citation14]. Despite more radiation-induced toxicity after SCRT with delayed surgery, significantly less postoperative complications were observed in this group compared with SCRT-IS. Nonetheless, concerns about delaying surgery after SCRT may include the risk of tumor repopulation [Citation34,Citation35]. Furthermore, the effect of SCRT with delayed surgery on QOL remains yet unknown. Studies investigating the optimal fractionation of neoadjuvant radiotherapy, with or without use of additional chemotherapy, and the optimal time interval to surgery to allow for organ preservation in intermediate risk rectal cancer are warranted. Besides, larger series of QOL following organ-sparing approaches are needed to support the assumption that patients’ QOL after organ preservation is indeed better than after radical surgery [Citation36].

In conclusion, this study suggests that the treatment strategy including CRT with delayed surgery may stronger impair patients’ QOL shortly after the start of rectal cancer treatment than SCRT with immediate surgery. However, longer-term QOL seems comparable between both groups, except for a slightly better emotional functioning after SCRT-IS. Furthermore, we showed that patients of both treatment strategies have poorer physical functioning up to 24 months compared with pretreatment status. These results emphasize and stimulate the need for shared- and evidence-based decision making regarding neoadjuvant rectal cancer treatment and its purposes.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (29.4 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Glynne-Jones R, Wyrwicz L, Tiret E, et al. Rectal cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. [Internet]. 2017;28:iv22–iv40. [cited 2018 Jan 17] Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28881920.

- Landelijke richtlijk colorectaal carcinoom en colorectale levermetastasen [Dutch national guideline colorectal cancer and colorectal liver metastases] version 3.0 [Internet]. 2014 [cited 2018 Jul 6]. Available from: https://richtlijnendatabase.nl.

- Bosset J-F, Collette L, Calais G, et al. Chemotherapy with preoperative radiotherapy in rectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1114–1123. [cited 2018 Jan 9] Available from: http://www.nejm.org/doi/abs/10.1056/NEJMoa060829.

- Gérard J-P, Conroy T, Bonnetain F, et al. Preoperative radiotherapy with or without concurrent fluorouracil and leucovorin in T3-4 rectal cancers: results of FFCD 9203. JCO. 2006;24:4620–4625. [cited 2018 Jan 9] Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17008704.

- Ortholan C, Francois E, Thomas O, et al. Role of radiotherapy with surgery for T3 and resectable T4 rectal cancer: evidence from randomized trials. Dis Colon Rectum. [Internet]. 2006;49:302–310. [cited 2018 Jan 9] Available from: http://content.wkhealth.com/linkback/openurl?sid=WKPTLP:landingpage&an=00003453-200649030-00002.

- Kapiteijn E, Marijnen CA, Nagtegaal ID, et al. Preoperative radiotherapy combined with total mesorectal excision for resectable rectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:638–646.

- Swedish Rectal Cancer T, Cedermark B, Dahlberg M, et al. Improved survival with preoperative radiotherapy in resectable rectal cancer. N Engl J Med. [Internet] 1997;336:980–987. [cited 2018 Jan 9] Available from: http://www.nejm.org/doi/abs/10.1056/NEJM199704033361402.

- Glimelius B. Optimal time intervals between pre-operative radiotherapy or chemoradiotherapy and surgery in rectal cancer? Front Oncol. [Internet] 2014;4:50. [cited 2018 Oct 8] Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24778990.

- van der Valk MJM, Hilling DE, Bastiaannet E, et al. Long-term outcomes of clinical complete responders after neoadjuvant treatment for rectal cancer in the International Watch & Wait Database (IWWD): an international multicentre registry study. Lancet. [Internet] 2018;391:2537–2545. [cited 2018 Jun 26] Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S014067361831078X.

- Zhou Z-R, Liu S-X, Zhang T-S, et al. Short-course preoperative radiotherapy with immediate surgery versus long-course chemoradiation with delayed surgery in the treatment of rectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Surg Oncol. [Internet]. 2014;23:211–221. [cited 2018 Jan 9] Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25466851.

- Wang X, Zheng B, Lu X, et al. Preoperative short-course radiotherapy and long-course radiochemotherapy for locally advanced rectal cancer: meta-analysis with trial sequential analysis of long-term survival data. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0200142. [cited 2018 Oct 8] Available from: http://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0200142.

- Bujko K, Nowacki MP, Nasierowska-Guttmejer A, et al. Long-term results of a randomized trial comparing preoperative short-course radiotherapy with preoperative conventionally fractionated chemoradiation for rectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2006;93:1215–1223. [cited 2018 Oct 8] Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/bjs.5506.

- Bujko K, Nowacki MP, Kepka L, et al. Postoperative complications in patients irradiated pre-operatively for rectal cancer: report of a randomised trial comparing short-term radiotherapy vs chemoradiation. Colorect Dis. 2005;7:410–416. [cited 2018 Oct 18] Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/j.1463-1318.2005.00796.x.

- Erlandsson J, Holm T, Pettersson D, et al. Optimal fractionation of preoperative radiotherapy and timing to surgery for rectal cancer (Stockholm III): a multicentre, randomised, non-blinded, phase 3, non-inferiority trial. Lancet Oncol. [Internet]. 2017;18:336–346. [cited 2017 Oct 12] Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28190762.

- Habr-Gama A, Perez RO, Nadalin W, et al. Operative versus nonoperative treatment for stage 0 distal rectal cancer following chemoradiation therapy: long-term results. Ann Surg. [Internet] 2004; [cited 2018 Jan 15]240:711–717-8. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15383798.

- Maas M, Beets-Tan RGH, Lambregts DMJ, et al. Wait-and-see policy for clinical complete responders after chemoradiation for rectal cancer. JCO. 2011;29:4633–4640. [cited 2017 Jul 19] Available from: http://ascopubs.org/doi/10.1200/JCO.2011.37.7176.

- Hoendervangers S, Couwenberg AM, Intven MPW, et al. Comparison of pathological complete response rates after neoadjuvant short-course radiotherapy or chemoradiation followed by delayed surgery in locally advanced rectal cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2018;44:1013–1017.

- McLachlan S-A, Fisher RJ, Zalcberg J, et al. The impact on health-related quality of life in the first 12 months: a randomised comparison of preoperative short-course radiation versus long-course chemoradiation for T3 rectal cancer (Trans-Tasman Radiation Oncology Group Trial 01.04). Eur J Cancer. 2016;55:15–26.

- Couwenberg AM, Burbach JPM, van Grevenstein WMU, et al. Effect of neoadjuvant therapy and rectal surgery on health-related quality of life in patients with rectal cancer during the first 2 years after diagnosis. Clin Colorectal Cancer 2018;17:e499–e512.

- Burbach JPM, Kurk SA, Coebergh van den Braak RRJ, et al. Prospective Dutch colorectal cancer cohort: an infrastructure for long-term observational, prognostic, predictive and (randomized) intervention research. Acta Oncol (Madr). [Internet] 2016;55:1273–1280. [cited 2017 Mar 3] Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27560599.

- Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, et al. The European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:365–376.

- Whistance RN, Conroy T, Chie W, et al. Clinical and psychometric validation of the EORTC QLQ-CR29 questionnaire module to assess health-related quality of life in patients with colorectal cancer. Eur J Cancer. [Internet]. 2009;45:3017–3026. [cited 2017 Mar 3] Available from: http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0959804909006510.

- van de Poll-Franse LV, Horevoorts N, Eenbergen M. v, et al. The Patient Reported Outcomes Following Initial treatment and Long term Evaluation of Survivorship registry: Scope, rationale and design of an infrastructure for the study of physical and psychosocial outcomes in cancer survivorship cohorts. Eur J Cancer. [Internet]. 2011;47:2188–2194. [cited 2016 Nov 15] Available from: http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0959804911003133.

- Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika. 1983;70:41–55. [cited 2018 Oct 4] Available from: https://academic.oup.com/biomet/article-lookup/doi/10.1093/biomet/70.1.41.

- Fayers PM, Aaronson NK, Bjordal K, et al. The EORTC QLQ-C30 scoring manual. 3rd ed. Brussels: European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer; 2001.

- Bonnetain F, Fiteni F, Efficace F, et al. Statistical challenges in the analysis of health-related quality of life in cancer clinical trials. JCO. 2016;34:1953–1956. [cited 2017 Aug 25] Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27091712.

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1988.

- Pietrzak L, Bujko K, Nowacki MP, et al. Quality of life, anorectal and sexual functions after preoperative radiotherapy for rectal cancer: report of a randomised trial. Radiother Oncol. [Internet]. 2007;84:217–225. [cited 2018 Jan 9] Available from: http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0167814007003532.

- Guckenberger M, Saur G, Wehner D, et al. Long-term quality-of-life after neoadjuvant short-course radiotherapy and long-course radiochemotherapy for locally advanced rectal cancer. Radiother Oncol. [Internet]. 2013;108:326–330. [cited 2017 Jun 23] Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24021342.

- Wiltink LM, Nout RA, van der Voort van Zyp JRN, et al. Long-term health-related quality of life in patients with rectal cancer after preoperative short-course and long-course (chemo) radiotherapy. Clin Colorectal Cancer. [Internet]. 2016;15:e93–e99. [cited 2017 Jun 23] Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26968237.

- van Zutphen M, Winkels RM, van Duijnhoven FJB, et al. An increase in physical activity after colorectal cancer surgery is associated with improved recovery of physical functioning: a prospective cohort study. BMC Cancer. [Internet] 2017;17:74. [cited 2018 May 10] Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28122534.

- Ngan SY, Burmeister B, Fisher RJ, et al. Randomized trial of short-course radiotherapy versus long-course chemoradiation comparing rates of local recurrence in patients with T3 rectal cancer: trans-tasman radiation oncology Group Trial 01.04. JCO. 2012;30:3827–3833. [cited 2018 May 9] Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23008301.

- Austin PC. Optimal caliper widths for propensity-score matching when estimating differences in means and differences in proportions in observational studies. Pharmaceut Statist. 2011;10:150–161. [cited 2018 Jan 9] Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20925139.

- Bujko K, Pietrzak L, Partycki M, et al. The feasibility of short-course radiotherapy in a watch-and-wait policy for rectal cancer. Acta Oncol (Madr). [Internet]. 2017;56:1152–1154. [cited 2018 Jul 6] Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/0284186X.2017.1327721.

- Glimelius B, Martling A. What conclusions can be drawn from the Stockholm III rectal cancer trial in the era of watch and wait? Acta Oncol (Madr). [Internet]. 2017;56:1139–1142. [cited 2018 Jul 6] Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/0284186X.2017.1344359.

- Hupkens BJP, Martens MH, Stoot JH, et al. Quality of Life in Rectal Cancer Patients After Chemoradiation. Dis Colon Rectum. [Internet] 2017;60:1032–1040. [cited 2018 Jan 11] Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28891846.