Abstract

Background: Oxaliplatin, combined with capecitabine (CAPOX) or infused 5-fluorouracil (FOLFOX), is standard of care in the adjuvant treatment of colorectal cancer (CRC). Prospective data on prevalence of oxaliplatin induced acute and long-term neuropathy in a real-life patient population and its effects on quality of life (QOL) and survival is limited, and scarce in CAPOX versus FOLFOX treated, especially in a subarctic climate.

Methods: One hundred forty-four adjuvant CRC patients (all 72 CAPOX cases and 72 matched FOLFOX controls) were analyzed regarding oxaliplatin induced sensory neuropathy, which was graded according to NCI-CTCAEv3.0. Ninety-two long-term survivors responded to the QOL (EORTC QLQ-C30) and Chemotherapy-Induced Peripheral Neuropathy (EORTC CIPN20) questionnaires and were interviewed regarding long-term neuropathy.

Results: Acute neurotoxicity was present in 94% (136/144) during adjuvant therapy and there was a significant association between acute neurotoxicity and long-term neuropathy (p < .001). Long-term neuropathy was present in 69% (grade 1/2/3/4 in 36/24/8/1%) at median 4.2 years. Neuropathy grades 2–4 did not influence global health status, but it was associated with decreased physical functioning (p = .031), decreased role functioning (p = .040), and more diarrhea (p = .021) in QLQ-C30 items. There were no differences in acute neurotoxicity, long-term neuropathy, or in QOL between CAPOX and FOLFOX treated. Neuropathy showed no pattern of variation according to starting and stopping month or treatment during winter.

Conclusions: Neuropathy following oxaliplatin containing adjuvant chemotherapy is present in two-thirds, years after cessation, and impairs some QOL scales. There is no difference in severity of acute or long-term neuropathy between CAPOX and FOLFOX treated and QOL is similar. No seasonal variation in neuropathy was noted.

Introduction

Nearly 1.8 million patients were diagnosed with colorectal cancer (CRC) in 2018 and it is predicted that 2.4 million new cases will be diagnosed annually worldwide by 2035 [Citation1]. More than half of newly diagnosed patients present with stage II or III cancer [Citation2] meaning they are candidates for adjuvant therapy. The 5-year relative survival rate is 64%, thus the number of CRC survivors is high [Citation2]. The efficacy of the adjuvant therapy is the major, but not the only, end-point, as toxicity and quality of life (QOL) in long-term survivors is a major cancer survivorship issue.

The survival benefit of adding oxaliplatin, to oral (i.e., CAPOX), bolus (FLOX) or infused (such as FOLFOX) fluoropyrimidines for stage II and III colon cancer, has been shown in three pivotal randomized studies [Citation3–5]. The addition of oxaliplatin offered a 4.5–5.1% improvement in disease free survival (DFS) at 3 years compared with fluoropyrimidines alone [Citation3–6].

The major problem with oxaliplatin is neurotoxicity. Hyperexitability of axons, changes in voltage-gated sodium and/or potassium channels causing repetitive discharges and oxidative stress, and neuronal damage caused by accumulation of oxaliplatin in the dorsal root ganglia, cause the symptoms of acute neurotoxicity and chronic oxaliplatin-induced neuropathy, respectively [Citation7]. Chronic neuropathy is the unwanted long-term adverse event after oxaliplatin-based adjuvant therapy, but its actual impact on long-term QOL is not well established.

Randomized data have shown that QOL in CRC survivors was good and the effect of additional fluoropyrimidine-treatment minor [Citation8,Citation9]. To our knowledge, no randomized QOL data with oxaliplatin in the adjuvant setting compared with fluoropyrimidines have been published. The number of studies investigating the prevalence of oxaliplatin induced long-term neuropathy and its effects on QOL in CRC survivors were scarce at the time of study initiation and are still limited. Variations in follow-up times and methods used to assess neuropathy make the magnitude of impairment difficult to assess [Citation10–13]. In addition, no randomized data were available on recovery from neuropathy after adjuvant CAPOX versus FOLFOX regimens. Only data based on physician’s choice between CAPOX and FOLFOX are available [Citation12,Citation13] and minimal regarding the differences in long-term QOL, especially in subarctic climate [Citation12].

Mild or moderate toxicity during adjuvant 5-fluorouracil therapy was associated with better survival in a French/Finnish retrospective study in stage II and III colorectal cancer patients and worst survival was noted in patients with no toxicity [Citation14]. The same was noted for mild leukopenia in a study in small-cell lung cancer [Citation15]. Skin toxicity and hypertension have been measures of efficacy in metastatic CRC and overall toxicity with chemotherapy response in sarcoma patients [Citation16–18].

We studied the prevalence of acute and long-term neuropathy with patient reported outcome measures (PROMs) and an extensive interview, in 72 CAPOX cases and 72 matched FOLFOX controls treated in a subarctic climate and the associations of acute and long-term neuropathy, QOL, winter treatment and prognosis.

Material and methods

We analyzed 144 stage II or III colorectal cancer patients who received adjuvant treatment with CAPOX (n = 72) or FOLFOX (n = 72) regimens at the Department of Oncology at Helsinki University Central Hospital (HUCH). The Ethical Review Board at Helsinki University Hospital, Helsinki, Finland, reviewed and approved the original and revised protocols.

Patient eligibility

All patients with histologically confirmed, radically operated stage II or III adenocarcinoma of colon or rectum, who had received adjuvant chemotherapy at the department of oncology at HUCH between 1.1.2000 and 30.9.2009 were reviewed. Seventy-two patients treated with the CAPOX regimen were identified (treatment initiated 31.10.2005–27.4.2009, with increasing frequency after the XELOXA results were presented [Citation5,Citation19]). After that, 72 FOLFOX treated controls were matched from the same database (treatment initiated 19.08.2004–5.5.2008). These controls were matched by sex, age (±5 years), colon or rectum, stage with maximum one difference in substage (i.e., IIIA to IIIB), and time period treated (±3 years).

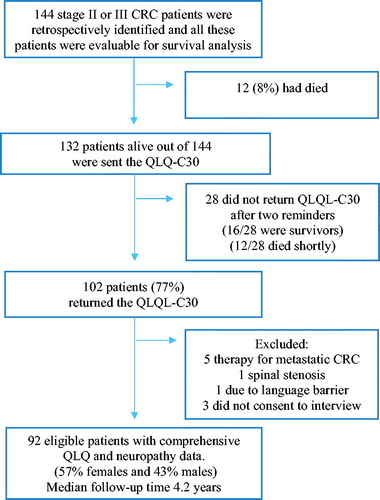

Ninety-two of these 144 patients were eligible (ineligibility: 12 deaths, six with confounding comorbidities, one with language barrier) and consented (30 did not send in consent ± questionnaires after two reminders, three did not consent for phone interview) for long-term neuropathy assessment and QOL analyses, details in Flowchart, . Response rate was 77% for questionnaires and phone interview. A written informed consent was obtained from all 102 patients that responded to the questionnaire.

Treatment regimens

The CAPOX regimen contained oxaliplatin 130 mg/m2 on day 1 as a 2-h infusion followed by capecitabine 2000 mg/m2 days 1–14 divided in two daily doses. Cycle was repeated every 21 d for approximately 24 weeks. The FOLFOX regimen consisted of oxaliplatin 85mg/m2 infusion day 1 together with leucovorin (LV) 400 mg/m2 followed by 5-FU bolus 400 mg/m2. Thereafter, continuous 5-FU infusion 2.4 g/m2 for 46 h was given. Cycle was repeated every 14 d for approximately 24 weeks. In rectal cancer, short course 25/5 Gy radiotherapy or long-course 50.4/1.8 Gy radiotherapy, with capecitabine or intravenous 5-FU as a chemosensitizer, were given preoperatively. Postoperative adjuvant treatment (with the same principles as in colon cancer), were given according to national guidelines. Postoperative radiotherapy was an exclusion criterion.

Chemotherapy-induced neuropathy

Assessment of acute neuropathy

Chemotherapy-induced sensory neuropathy graded per criteria according to National cancer institute common toxicity criteria version 3.0 (NCI-CTCAE v3.0) was assessed from patient files in all 144 patients. In version 3.0, grade 1 neuropathy is defined as asymptomatic, grade 2 interfering with function but not with activities of daily living (ADL), grade 3 interfering with ADL, and grade 4 as disabling. Acute neuropathy was defined as worst grade of sensory neuropathy during the treatment or within 2 months after stopping the treatment. The sensory grade was worse than motor neuropathy in all patients and used in the results section.

Assessment of long-term neuropathy and QOL

Neuropathy assessed later than two months after the end of therapy was defined as long-term. Patients alive (n = 132) were contacted by mail and by two reminders for non-responders (). There were no official translations (into Finnish or Swedish) of this questionnaire by the time of the study and, therefore, CIPN20 was filled in during the phone interview together with the patient, based on an unofficial translation, with the permission from EORTC. CIPN20 contains three subscales assessing sensory, motor, and autonomic symptoms. Each item is scored from 1 (not at all) to 4 (very much) and further linearly transformed to a 0–100 scale, with higher scores representing more symptoms.

EORTC QLQ-C30 (version 3.0) was used to assess QOL. It contains five functional scales, a global health status QOL scale, three symptoms scales, and six single item scores. Each item was scored from 1 (not at all) to 4 (very much), except the global QOL scale which ranges from 1 (very poor) to 7 (excellent), and scores were linearly transformed to a 0–100 scale. The higher scores represent better functioning on the functional scales and global QOL, whereas higher scores on the symptom scales signified more complaints.

Seasonal variation

The mean temperature in Helsinki for each month of the study was retrieved from the The Finnish Meteorological Institute statistics (https://en.ilmatieteenlaitos.fi/statistics-from-1961-onwards). Acute and long-term neuropathy was correlated with oxaliplatin starting and stopping month. The data were also dichotomized according to if the patient received oxaliplatin in the two coldest months (January and February) or not i.e., if they had the majority of their treatment during winter months.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were presented as medians with the corresponding range and categorical variables as frequencies with the respective percentages.

Grade 2 or worse neuropathy was considered as clinically significant and therefore grade 0–1 versus 2–4 was used as a cutoff for acute and long-term neuropathy. Chi-square and the non-parametric Mann–Whitney U tests were used for comparing the baseline characteristics and the outcome variables between the groups. Spearman’s rho test was used to test the correlations between continuous variables. Logistic regression analysis was used to test the predictive value of different variables for acute neurotoxicity and long-term neuropathy. Following variables were selected for the multivariate model: age, gender, ECOG performance status, treatment arm, predisposing diabetes, cumulative dose of oxaliplatin or whether the patient received oxaliplatin during January or February. For the model for long-term neuropathy, also the follow-up time and the presence of acute neuropathy grade 2–4 were included. For all tests, significance level was set at α = 0.05. No adjustment for multiple comparisons was done.

Data for relapse and survival analysis were updated for all 144 patients from patient files and national registries. No patients were lost to follow-up and all patients were treated at HUCH after relapse. These data were updated as of 30 June 2017. Median survival is, therefore, longer than the follow-up time for neuropathy and QOL analysis. OS was measured from the date of treatment initiation to the date of death or censored at last follow-up, while DFS was measured from the date of treatment initiation to documented first recurrence, death without prior documented recurrence or censored at last follow-up, whichever occurred first. Time to event distributions were estimated using Kaplan–Meier curves and compared using log-rank tests.

Graph Pad Prism version 6.00 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA), Sigmaplot version 11.0 (Systat Software Inc, Cary, NA), and SPSS version 24.0 (IBM Corp., IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 24.0. Armonk, NY) were used for statistical analyses.

Results

Patient characteristics

Patient characteristics are presented in . In all 144 patients, the CAPOX and FOLFOX arms were well balanced by age, gender, stage, tumor site, cumulative dose of oxaliplatin, and its weekly dose-intensity. The median age of patients was 61 years (range, 25–77 years) and 58% of the patients were female. Colon cancer was the primary tumor site in 62% (and rectal cancer in 38%). Of all patients, 85% presented with stage III disease.

Table 1. Patient characteristics.

In the 92 patients, evaluable for long-term neuropathy and QOL analysis, the CAPOX and FOLFOX arms () were well balanced, except for median age (63 versus 59 years, p = .040).

There was no significant correlation between the mean temperature of the oxaliplatin starting month or the oxaliplatin stopping month and the duration of oxaliplatin treatment (Spearman’s rho= −0.1, p = .18 and −0.1, p = .15, respectively) or the oxaliplatin cumulative dose (Spearman’s rho= −0.1, p = .23 and −0.1, p = .23, respectively). The cumulative dose of oxaliplatin was higher in the winter group (i.e., receiving oxaliplatin in January or February), median 805 versus 705 (p = .007). shows more detailed data about the variables according to the starting month.

Table 2. Oxaliplatin starting month with number of patients, mean temperature, mean duration of oxaliplatin treatment, and percentage (%) of patients with acute grades 2–4 neurotoxicity and long-term grades 2– neuropathy.

Acute neuropathy (n = 144)

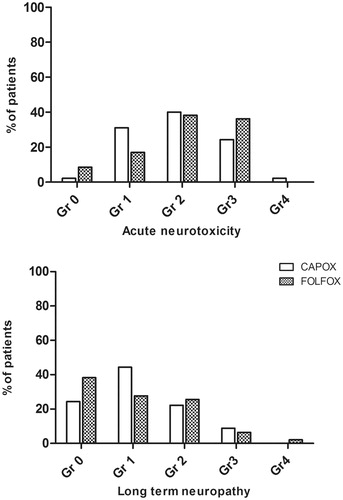

Any grade sensory neuropathy during chemotherapy occurred in 136 (94%) out of 144 patients and was grade 1 in 24%, 2 in 45%, 3 in 25%, and 4 in 1% of the patients. Sensory neuropathy was mostly cold allodynia and laryngospasm as acute toxicity, and numbness, with/without effect on ADL, as cumulative toxicity. There was no difference in the prevalence of acute neuropathy between CAPOX and FOLFOX groups (p = .22, ).

Figure 2. Proportion of patients with different grades of acute neurotoxicity (upper panel) and long-term neuropathy (lower panel) in CAPOX and FOLFOX groups. There were no statistically significant differences between the groups (Chi-square).

Among the 57 patients who received oxaliplatin during the winter period, the percentage of grade 2–4 acute neuropathy was 72% compared with 70% among the remaining 87 patients (p = .80) and frequency of dose reductions was similar (41/57 [72%] versus 65/87 [75%], p = .43). There were no differences in the temperature of the oxaliplatin starting or stopping month between patients with grade 2–4 acute neuropathy compared to patients with grade 0–1 (p = .90 and =.68, respectively) and there was no difference in length of oxaliplatin treatment ().

In univariate or multivariate analysis, none of the following tested variables: age, gender, ECOG performance status, tumor site, treatment arm, predisposing diabetes, weekly dose intensity, cumulative dose of oxaliplatin or whether the patient received oxaliplatin in winter, predicted acute neuropathy (multivariate model in ).

Table 3. Predictors of acute neurotoxicity and long-term neuropathy from the multivariate logistic regression models, with odds ratio (OR), 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and p value (p).

Long-term neuropathy (n = 92)

At the median follow-up time of 4.2 (range 2.6–8.9) years sensory neuropathy was present in 63 (69%) patients, grade 1 in 36%, grade 2 in 24%, grade 3 in 8%, and grade 4 in 1%. Two patients with grade 3 neuropathy had retired due to impaired dexterity and a patient with grade 4 neuropathy was disabled and confined to a wheelchair due to severe sensory deficits and ataxia.

Acute neurotoxicity worsened from grades 0 to 1 during therapy to clinically significant long-term neuropathy grades 2 and 3 in 36% (5/14). In five patients without any acute neurotoxicity during treatment, two developed long-term neuropathy grades 2 and 3. Acute neurotoxicity grades 2–4 during therapy improved to long-term neuropathy grades 0 and 1 in 61% (40/65), but remained grades 3 and 4 in 11% (7/65). If oxaliplatin treatment duration was ≤3 months, 38% (5/13) had long-term neurotoxicity grades 2–4 and if >3 months 32% (25/79).

There were no differences in the mean temperature of the oxaliplatin starting or stopping month between patients with grades 2–4 versus 0 and 1 long-term neuropathy (p = .35 and p = .68), in treatment duration or in cumulative dose () or in dose reductions. Treatment in winter was not significantly associated with the grades 2–4 long-term neuropathy (), or worse tingling/numbness of hands or feet according to CIPN20 scores.

The prevalence of long-term neuropathy was similar between CAPOX and FOLFOX groups (p = .35, ) and there were no major differences in median cumulative dose (780 versus 765 mg/m2, respectively), dose intensity (32.5 versus 31.9 mg/m2/week), or duration of oxaliplatin treatment (4.9 versus 4.6 months) or dose reductions between the treatment groups.

In multivariate analysis, only ECOG performance status was significantly associated with long-term neuropathy. In patients with ECOG 0, the prevalence of long-term neuropathy grade 2-4 was 27% (20/73) compared with 53% (10/19) in ECOG 1 (OR 3.9, CI95% 1.3–12.2; ). Long-term neuropathy was more common in patients who had grades 2–4 acute neurotoxicity (38.5% versus 18.5%, p < .001 Chi square, OR in multivariate model 3.1, CI95% 0.95–10.3).

Chemotherapy induced peripheral neuropathy, CIPN20 (n = 92)

The patients reporting ‘any’, ‘quite a bit’, or ‘severe’ symptoms in the different items in the CIPN20 questionnaire are presented in . The most common symptoms were numbness of feet and/or toes (any in 60% and severe in 21%) and numbness in hands and/or in fingers (any in 36% and severe in 7%).

Table 4. Number (n = 92) and proportion of patients reporting any grade (‘A little’, ‘Quite a bit’, or ‘Very much’) or severe (‘Quite a bit’ or ‘Very much’) symptoms on a EORTC QLQ-CIPN20 questionnaire at the long-term follow up (median 4.2 years, range 2.6–8.9).

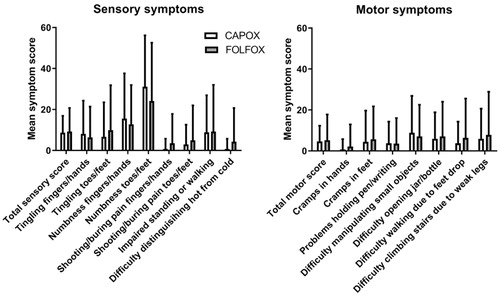

represents the mean symptom scores for different items in the EORTC QLQ-CIPN20 questionnaire for the CAPOX and FOLFOX groups. There were no statistically significant differences between the treatment regimens for total motor score, total sensory score, total autonomic score, or any of the individual items.

Figure 3. Symptom scores for sensory (left) and motor (right) items in the EORTC QLQ-CIPN20 questionnaire for CAPOX and FOLFOX groups. Higher scores mean more symptoms/problems. Data are presented as mean values with standard deviation. There were no statistically significant differences between the groups (Mann–Whithey U test).

Quality of life, QLQ-C30 (n = 92)

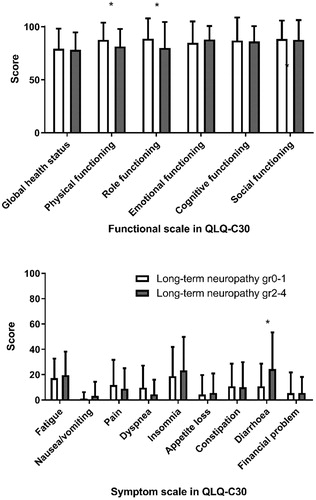

The presence of long-term neuropathy grades 2–4 was significantly associated with decreased physical functioning (mean score 81.8 versus 87.8, p = .031) and role functioning (mean score 80.0 versus 89.3 p = .040), but not with global health status, emotional, cognitive, or social functioning (). Of the symptom scales, diarrhea was significantly more common among patients with long-term neuropathy grades 2–4 (mean score 24.4 versus 10.9, p = .021, ).

Figure 4. Mean scores (with upper limit of 95% confidence interval) of functional (above) and symptom (below) scales in QLQ-C30, in patients with long term neuropathy grades 0 and 1 and in patients with long-term neuropathy grades 2–4. *Statistically significant difference between the groups.

Among the eight patients with grades 3–4 long-term neuropathy the global health status was also similar as in grades 0–2 patients (mean score 75.0 versus 79.3, p = .37). The scales with significantly lower scores in these patients were role functioning (mean score 60.4 versus 88.8, p <.001) and financial problems (mean score 16.7 versus 4.4, p = .002).

There were no statistically significant differences between CAPOX and FOLFOX arms in the global health status scores or any other of the QLQ-C30 subscales (data not shown).

Disease-free and overall survival

Survival was assessed for all the 144 patients at median follow-up time of 9.2 years (range 5.8–15.4). There was a numerical trend favoring DFS (censored 74 versus 63%; p = .21, Supplementary Figure 5, upper panel) or OS (censored 75 versus 69%; p = .30) in the CAPOX versus FOLFOX arm. A numerical trend favoring OS in the group of patients experiencing grades 2–4 acute neurotoxicity was noted (censored 75 versus 69%, p = .43; Supplementary Figure 5, lower panel).

Discussion

In the present study, neuropathy following oxaliplatin containing adjuvant chemotherapy is present in a significant number of patients, years after cessation of chemotherapy, being severe in some. There is no difference in the frequency or severity of neuropathy between CAPOX and FOLFOX regimens during the therapy or in follow-up. In addition, the long-term QOL is equal in patients treated with either regimen. Neuropathy does not impair global health status but may impair social and role functioning and is associated with more diarrhea. Acute neurotoxicity and performance status predict long-term neuropathy, but predisposing age, gender, time from treatment, diabetes, cumulative dose and dose-intensity of oxaliplatin, winter dosing or limiting treatment to at the most 3 months did not. The presence of long-term neuropathy may be prognostic for survival.

Acute neuropathy grades 1–4 occurred in 94% of patients in our study which is in line with one (92%) [Citation3], but higher than two of the registration studies 70–78% [Citation4–6]. We report grades 3 and 4 neurotoxicity during adjuvant therapy in 26% of patients which is more than reported in the registration studies (8–13%) and in the randomized study comparing CAPOX and FOLFOX in the adjuvant setting [Citation20], and similar as in the metastatic setting comparison [Citation21].

Long-term neuropathy grades 3 and 4 diminishes to 0.6–0.7% at a median follow-up of 1.5–7 years in the registration studies, but any grade persistent neuropathy is present in 16–24–29–68% [Citation3–6,Citation22–24]. Significantly higher neuropathy figures of 60–89%, when assessed with PROMs or neurosensory testing have been reported [Citation11,Citation25,Citation26], which is in line with our findings of 69%.

The risk of long-term neuropathy has been associated with cumulative dose of oxaliplatin in some studies [Citation13,Citation26,Citation27], but not in all [Citation12,Citation28]. In the three registration studies, less neuropathy was noted in the study with 25% lower cumulative dose [Citation4,Citation6]. In the IDEA consortium study (n = 12,834), grades 2–4 acute neurotoxicity was reported in 15–17% in the three month arms, compared with 45–48% in the six month arms with 23–25% higher cumulative dose [Citation29], presumably leading to less long-term neuropathy, but these data are not mature yet. In our study, we did not see a significant association between the cumulative dose of oxaliplatin and the risk of acute or long-term neuropathy. Apart from the small sample size, this may be due to the high median cumulative dose of 770 mg/m2 (74%), compared with the IDEA and the Swedish studies (567–757 mg/m2) [Citation12,Citation29], but similar to the registration studies [Citation3–6].

In our study, the most common neuropathy symptoms are numbness and tingling of feet/toes and hands/fingers, which is well in line with previous reports [Citation3,Citation11–Citation13]. The rates of numbness are quite similar, but higher means and standard deviations for tingling in the Dutch and Swedish studies may be explained by shorter follow-up times in some patients [Citation12,Citation13], and that CIPN was graded over the phone in our patients. The extensive interview probably led to better definition and understanding of the items and correct toxicities were denoted, but severity of symptoms might have been diluted, as compared with the PROMs.

Data concerning higher prevalence of acute and long-term neuropathy in the subarctic climate is scarce and very little is published on seasonal variation. A Danish patient series demonstrated higher acute neurotoxicity leading to dose reductions in the second cycle if treatment was given during winter months [Citation30]. The Swedish study had no data on dose reductions during therapy [Citation12]. We had no excess dose reductions in the winter period. The Swedish series noted a numerically 10% higher cumulative dose in the summer period, but our results were reverse with 12% higher dose in winter [Citation12], thus the assumption of lower cumulative dose in winter could not be verified. Contrary to the Swedish finding, we had no worse tingling or numbness in winter [Citation12]. As seen in the Danish study and discussed in the Swedish one, in clinical practice, it is easier to treat patients with oxaliplatin during summer than in winter, but seasonal variation has no impact on acute or long-term neuropathy in our study. The subarctic climate itself is probably more important than seasonal variation.

Performance status ECOG >0 is a predictor for long-term neuropathy in our study, but not for acute neurotoxicity. In a study by Lewis et al., acute neuropathy is worse in ECOG >0 both in the adjuvant and metastatic settings [Citation31]. This finding needs further validation in larger datasets. Apart from the ECOG performance status, our findings are in line with previous studies since no other baseline factor (age, gender, diabetes, etc.) is predictive for acute or long-term neuropathy [Citation33,Citation33].

There are no differences in acute neurotoxicity, long-term neuropathy or QoL between CAPOX and FOLFOX treatment regimens in our study. This is in line with acute neurotoxicity data, that was similar in recently published randomized adjuvant studies, with random allocation to treatment arm in one and physician’s choice in the latter [Citation20,Citation29]. Long-term neuropathy was also as frequent in an adjuvant patient series with some CAPOX treated and a small number of FOLFOX treated [Citation13]. QOL data were similar with CAPOX and FOLFOX treated in the Swedish study [Citation12].

There are no differences in survival between treatment regimens, even though there is a small trend favoring the CAPOX arm, with possible support from physician’s choice of CAPOX regimen data from the IDEA study and a retrospective patient series by Loree et al. [Citation29,Citation34], but not from a small randomized study [Citation20]. A numerical trend for improved survival was noted in patients with acute neurotoxicity, but the patient numbers are too small for any prognostic conclusions. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to look at the prognostic impact of chemotherapy-induced neurotoxicity in the adjuvant setting of CRC, and this should be looked at in larger datasets, for example the ACCENT database [Citation35].

We do not observe significant impairment in global health status by long-term neuropathy, but subscales like physical and role functioning are significantly impaired in line with previous findings [Citation10–Citation12]. In the longitudinal substudy of SCOT, patients with severe numbness, tingling, or discomfort in their hands or feet have significantly lower QOL for up to 5 years [Citation36]. Similarly, among 163 patients included in the cross-sectional PROFILES registry, the 10th percentile of patients with severe neuropathy have worse QOL scores on all EORTC QLQ-C30 subscales [Citation10]. One aspect affecting QOL assessments, especially the global score, is a phenomenon called reframing, when the perception of QOL is affected by the life-threating disease i.e., cancer [Citation37]. As our patient, who had retired due to impaired dexterity, told us: ‘Neuropathy is a low price to pay for being alive’.

Our study has several limitations. The major limitation is lack of randomization and the modest patient number. A minor limitation is that CIPN20 assessment is performed by extensive interview and not as a questionnaire and may explain the lower mean scores in CIPN20. The participation rate is reasonable (77%) and could not be improved further with postal or phone reminders. Our study has several strengths. The major strength is the real-life patient population, including all consecutive CAPOX treated patients, with matched FOLFOX controls during 4.5 years at a big institution, with only five treating consultants. The follow-up time of median 4.2 years is long and further improvement in neurotoxicity is thus unlikely. Cross-comparison of acute neurotoxicity and long-term neuropathy, as well as, NCI-CTCAE grading in addition to CIPN20 outcomes, makes comparison to previously published series easier. The patient’s view and perceptions are highlighted in the extensive interview performed by a single consultant. We saw no gender differences in non-responders.

In conclusion, we show in a real-life patient population from a subarctic region that oxaliplatin containing chemotherapy may lead to persistent neuropathy in two thirds of patients, being severe in nearly one-tenth. There is an association between on-treatment neurotoxicity and long-term neuropathy, but significant worsening of seemingly harmless acute neurotoxicity is seen in one third. Performance status ECOG >0 at baseline may be a significant risk factor for long-term neuropathy, but diabetes, cumulative dose of oxaliplatin, weekly dose intensity or dosing during subarctic winter does not predict clinically significant long-term toxicity.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (83.2 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, et al. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394–424.

- Ahmed S, Johnson K, Ahmed O, et al. Advances in the management of colorectal cancer: from biology to treatment. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2014;29:1031–1042.

- Andre T, Boni C, Mounedji-Boudiaf L, et al. Oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin as adjuvant treatment for colon cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2343–2351.

- Kuebler JP, Wieand HS, O'Connell MJ, et al. Oxaliplatin combined with weekly bolus fluorouracil and leucovorin as surgical adjuvant chemotherapy for stage II and III colon cancer: results from NSABP C-07. JCO. 2007;25:2198–2204.

- Haller DG, Tabernero J, Maroun J, et al. Capecitabine plus oxaliplatin compared with fluorouracil and folinic acid as adjuvant therapy for stage III colon cancer. JCO. 2011;29:1465–1471.

- Land SR, Kopec JA, Cecchini RS, et al. Neurotoxicity from oxaliplatin combined with weekly bolus fluorouracil and leucovorin as surgical adjuvant chemotherapy for stage II and III colon cancer: NSABP C-07. JCO. 2007;25:2205–2211.

- Beijers AJM, Mols F, Vreugdenhil G. A systematic review on chronic oxaliplatin-induced peripheral neuropathy and the relation with oxaliplatin administration. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22:1999–2007.

- Norum J, Vonen B, Olsen JA, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy (5-fluorouracil and levamisole) in Dukes' B and C colorectal carcinoma. A cost-effectiveness analysis. Ann Oncol: Off J Eur Soc Med Oncol. 1997;8:65–70.

- Gray RG, Barnwell J, Hills R, et al. QUASAR: a randomized study of adjuvant chemotherapy (CT) vs observation including 3238 colorectal cancer patients. JCO. 2004;23:A3501.

- Mols F, Beijers T, Lemmens V, et al. Chemotherapy-induced neuropathy and its association with quality of life among 2- to 11-year colorectal cancer survivors: results from the population-based PROFILES registry. JCO. 2013;31:2699–2707.

- Tofthagen C, Donovan KA, Morgan MA, et al. Oxaliplatin-induced peripheral neuropathy's effects on health-related quality of life of colorectal cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21:3307–3313.

- Stefansson M, Nygren P. Oxaliplatin added to fluoropyrimidine for adjuvant treatment of colorectal cancer is associated with long-term impairment of peripheral nerve sensory function and quality of life. Acta Oncol. 2016;55:1227–1235.

- Beijers AJ, Mols F, Tjan-Heijnen VC, et al. Peripheral neuropathy in colorectal cancer survivors: the influence of oxaliplatin administration. Results from the population-based PROFILES registry. Acta Oncol. 2015;54:463–469.

- Soveri LM, Hermunen K, de Gramont A, et al. Association of adverse events and survival in colorectal cancer patients treated with adjuvant 5-fluorouracil and leucovorin: is efficacy an impact of toxicity? Eur J Cancer. 2014;50:2966–2974.

- Liu W, Zhang C-C, Li K. Prognostic value of chemotherapy-induced leukopenia in small-cell lung cancer. Cancer Biol Med. 2013;10:92–98.

- Van Cutsem E, Tejpar S, Vanbeckevoort D, et al. Intrapatient cetuximab dose escalation in metastatic colorectal cancer according to the grade of early skin reactions: the randomized EVEREST study. JCO. 2012;30:2861–2868.

- Cai J, Ma H, Huang F, et al. Correlation of bevacizumab-induced hypertension and outcomes of metastatic colorectal cancer patients treated with bevacizumab: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Surg Oncol. 2013;11:306.

- McTiernan A, Jinks RC, Sydes MR, et al. Presence of chemotherapy-induced toxicity predicts improved survival in patients with localised extremity osteosarcoma treated with doxorubicin and cisplatin: a report from the European Osteosarcoma Intergroup. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48:703–712.

- Schmoll HJ, Tabernero J, Nowacki M, et al. Early safety findings from a phase III trial of capecitabine plus oxaliplatin (XELOX) vs. bolus 5-FU/LV as adjuvant therapy for patients (pts) with stage III colon cancer. JCO. 2005;24:A3523.

- Pectasides D, Karavasilis V, Papaxoinis G, et al. Randomized phase III clinical trial comparing the combination of capecitabine and oxaliplatin (CAPOX) with the combination of 5-fluorouracil, leucovorin and oxaliplatin (modified FOLFOX6) as adjuvant therapy in patients with operated high-risk stage II or stage III colorectal cancer. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:384.

- Ducreux M, Bennouna J, Hebbar M, et al. Capecitabine plus oxaliplatin (XELOX) versus 5-fluorouracil/leucovorin plus oxaliplatin (FOLFOX-6) as first-line treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer. Int J Cancer. 2011;128:682–690.

- Kidwell KM, Yothers G, Ganz PA, et al. Long-term neurotoxicity effects of oxaliplatin added to fluorouracil and leucovorin as adjuvant therapy for colon cancer: results from National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project trials C-07 and LTS-01. Cancer. 2012;118:5614–5622.

- Schmoll HJ, Cartwright T, Tabernero J, et al. Phase III trial of capecitabine plus oxaliplatin as adjuvant therapy for stage III colon cancer: a planned safety analysis in 1,864 patients. JCO. 2006;25:102–109.

- André T, Boni C, Navarro M, et al. Improved overall survival with oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin as adjuvant treatment in stage II or III colon cancer in the MOSAIC trial. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3109–3116.

- Beijers A, Mols F, Dercksen W, et al. Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy and impact on quality of life 6 months after treatment with chemotherapy. J Community Support Oncol. 2014;12:401–406.

- Park SB, Lin CS, Krishnan AV, et al. Long-term neuropathy after oxaliplatin treatment: challenging the dictum of reversibility. Oncologist. 2011;16:708–716.

- Iveson TJ, Kerr RS, Saunders MP, et al. 3 Versus 6 months of adjuvant oxaliplatin-fluoropyrimidine combination therapy for colorectal cancer (SCOT): an international, randomised, phase 3, non-inferiority trial. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19:562–578.

- Brouwers EE, Huitema AD, Boogerd W, et al. Persistent neuropathy after treatment with cisplatin and oxaliplatin. Acta Oncol. 2009;48:832–841.

- Grothey A, Sobrero AF, Shields AF, et al. Duration of adjuvant chemotherapy for stage III colon cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1177–1188.

- Zhong J, Ali AN, Voloschin AD, et al. Bevacizumab-induced hypertension is a predictive marker for improved outcomes in patients with recurrent glioblastoma treated with bevacizumab. Cancer. 2015;121:1456–1462.

- Lewis MA, Zhao F, Jones D, et al. Neuropathic symptoms and their risk factors in medical oncology outpatients with colorectal vs. breast, lung, or prostate cancer: results from a Prospective Multicenter Study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2015;49:1016–1024.

- Morel A, Boisdron-Celle M, Fey L, et al. Clinical relevance of different dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase gene single nucleotide polymorphisms on 5-fluorouracil tolerance. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5:2895–2904.

- Pulvers JN, Marx G. Factors associated with the development and severity of oxaliplatin-induced peripheral neuropathy: a systematic review. Asia-Pac J Clin Oncol. 2017;13:345–355.

- Caudle KE, Thorn CF, Klein TE, et al. Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium guidelines for dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase genotype and fluoropyrimidine dosing. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2013;94:640–645.

- Renfro LA, Shi Q, Sargent DJ. Mining the ACCENT database: a review and update. Chin Clin Oncol. 2013;2:18.

- Wolmark N, Rockette H, Fisher B, et al. The benefit of leucovorin-modulated fluorouracil as postoperative adjuvant therapy for primary colon cancer: results from National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project protocol C-03. JCO. 1993;11:1879–1887.

- Bernhard J, Hurny C, Maibach R, et al. Quality of life as subjective experience: reframing of perception in patients with colon cancer undergoing radical resection with or without adjuvant chemotherapy. Swiss Group for Clinical Cancer Research (SAKK)[see comment]. Ann Oncol. 1999;10:775–782.