Abstract

Objectives: Financial difficulties experienced by cancer patients may affect their health-related quality of life (HRQoL). This study assessed the direct economic burden that out-of-pocket (OOP) payments cause and explored how they and financial difficulties are associated with HRQoL.

Methods: This is a cross-sectional registry and survey study of 1978 cancer patients having either prostate (630), breast (840) or colorectal cancer (508) treated in Finland. The patients were divided into five groups according to the stage of their disease: primary treatment, rehabilitation, remission, metastatic disease and palliative care. The cost data and OOP payments were retrieved from primary and secondary healthcare registries, the Social Insurance Institution of Finland, and a patient questionnaire. HRQoL was measured by 15D, EQ-5D-3L and by EORTC-QLQ-C30. Financial difficulties were evaluated based on patients’ self-assessment in the EORTC-QLQ-C30 four-level question about financial difficulties. A path analysis was used to explore the relationship between clinical and demographic factors, HRQoL, OOP payments and financial difficulties.

Results: The highest OOP payments were caused by outpatient medication. Total costs and OOP payments were highest in the palliative care group in which the OOP payments consisted mostly of outpatient medication and public sector specialist care. Private sector health care was an important item of OOP payments in the early stages of cancer. Financial difficulties increased together with OOP payments. HRQoL deteriorated the more a person had financial difficulties. In the path analysis, financial difficulties had a major negative direct and total effect on the HRQoL. Factors that attenuated financial difficulties were age, cohabiting and higher education and factors that increased them were OOP payments, total costs of healthcare use, and unemployment.

Conclusions: High OOP payments are related to financial difficulties, which have a negative effect on HRQoL. Outpatient medication was a major driver of OOP payments. Among palliative patients, the economic burden was highest and associated with impaired HRQoL.

Introduction

Cancer can have many financial implications for patients and their families [Citation1]. For example, patients have to pay for medications, travel costs and be absent from work. New therapies improve survival but as a consequence increase the cumulative cost per patient. The share patients need to pay out-of-pocket (OOP) consists of co-payments and fees.

Among chronically ill patients, financial difficulties can have adverse health effects [Citation1,Citation2]. It has been reported earlier that financial difficulties have a negative effect on cancer patients’ health-related quality of life (HRQoL). Financial difficulties are common among advanced cancer patients and they are known to cause anxiety, depression and impaired quality of life [Citation3–5].

The degree of financial difficulties a cancer causes for a patient varies depending on several factors such as socioeconomic status and type of the disease. Treatments can involve OOP payments that affect patients’ well-being in a negative manner, a phenomenon known as financial toxicity [Citation6].

The amount a person has to pay himself and the amount covered by insurance or public healthcare system varies by country. The Finnish healthcare system, in which everyone is covered by social security, aims to moderate the effects of chronic diseases on the financial situation of individual patients. Despite that, the OOP payments in the Finnish healthcare system are high compared to other OECD countries.

The number of studies considering cancer-related financial difficulties in countries with social security and universal healthcare coverage is limited. More studies are needed to determine whether a publicly funded healthcare system is able to protect cancer patients from financial toxicity.

Healthcare costs vary substantially depending on the disease state. In our earlier study on colorectal cancer patients, mean direct healthcare costs were found to be highest in the early stages of the disease. During remission, the costs were moderate but then increased markedly again in the metastatic and palliative stages of cancer [Citation7].

In a study on prostate cancer patients, mean direct health care costs and productivity costs were highest among patients in the metastatic state of the disease [Citation8].

The aim of this study is to examine the relationship between financial difficulties and HRQoL among breast, prostate and colorectal cancer patients in different stages of the disease as well as to calculate the total financial burden to patients caused by cancer. Furthermore, we wanted to identify patient characteristics that are associated with financial difficulties and HRQoL and identified factors affecting the costs.

Material and methods

Study population

This analysis is part of a cross-sectional study of altogether 1978 cancer patients having either prostate, breast or colorectal cancer [Citation5,Citation9]. Of the patients, 630 had prostate cancer, 840 breast cancer and 508 colorectal cancer. The study participants were selected to represent all disease states from diagnosis to end-of-life care. They were approached by mail or when visiting the hospital. Based on time from diagnosis, the presence of metastases, or a palliative care decision, participants were divided into five mutually exclusive groups: primary disease (0–6 months from diagnosis), rehabilitation (6–18 months from diagnosis), remission (subsequent years in remission), metastatic disease (active oncological treatments) and palliative care. Extensive data on resource use and costs were collected from several registries. Furthermore, patients completed three HRQoL questionnaires and in addition were asked about their demographic background information, education, work and marital status, cancer-related absence from work and informal care received due to cancer. The only exclusion criterion was age under 18 years. The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Helsinki University Hospital and written informed consent was received from all participants. The patients were recruited between 2009 and 2011.

Cost data

Resource use and cost data covered the preceding six-month period before completion of the HRQoL questionnaires. All healthcare costs were included irrespective of whether they were related to cancer. In the Finnish healthcare system, OOP payments are defined by law and they were calculated based on resource use data. The resource use and cost data associated with secondary healthcare use were extracted from hospital records. The data included information about the length of the hospitalization or visit, procedures and examinations done and patient level costs, including overheads, equipment and drugs for inpatient use. In hospitals, the OOP payments consist of fees for outpatient visits, inpatient care, home care, serial treatment and day surgery procedures.

The resource use data in primary healthcare were extracted from patients’ home municipality and they were available for 1550 patients (78% of our study population) from the three largest cities in the area, Helsinki, Espoo and Vantaa. The missing data for the 428 patients living outside the three biggest cities were imputed using cancer type and state group mean values. The data contain information on GP and nurse visits, home hospice care and primary care hospitalizations.

Public healthcare is universally provided and comprehensive in Finland. The role of private healthcare is mostly complementary. Private healthcare expenditure is partially reimbursed by the National Social Insurance Institution of Finland (SII) to patients, but as the reimbursement covers only a small proportion of the private healthcare fees, OOP payments for private healthcare are high. Data on visits to private physicians and costs were available from the SII registries. Outpatient medicines are partially reimbursed by the SII and the cost and OOP payments data were available from their registries. Cancer medicines are fully reimbursed to patients. For other drugs, the reimbursement varies from 42% to 100%. The maximum combined amount of OOP payments for primary healthcare and specialist care yearly is 633 euros. Costs beyond that are paid by the municipality in which the patient lives.

The costs of travel to GP or to a hospital were included if they exceeded the maximum out of pocket payment which is 14 euros per journey. The number of journeys and costs were available from the registers of the SII allowing us to calculate the patients’ OOP payments. In this analysis, we did not include the cost and financial burden to patients caused by productivity loss or by informal care.

The monetary value of the used medical services and resources was estimated for a six-month period based on register data of the municipalities providing primary care treatment and of the social insurance institution of Finland (SII) covering the costs of medications and part of sick leaves in Finland. Furthermore, data on the use of specialized medical care were obtained from hospital electronic records. Data on demographic factors and self-reported use of health-related services were collected by a background questionnaire.

All costs are in euros and are calculated at the 2010 price level. All other currencies were converted to euros using the exchange rate of 31 December 2010.

HRQoL data

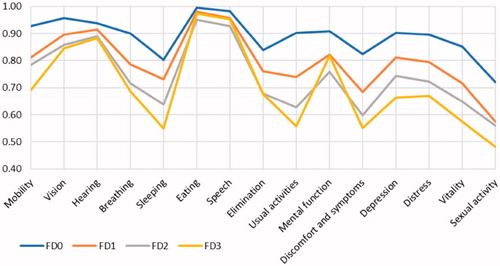

HRQoL was measured by two generic HRQoL instruments, the 15D and the EQ-5D-3L, and by the cancer-specific EORTC-QLQ-C30 instrument. The 15D provides a single index score between 0 and 1 and a health profile with 15 dimensions (mobility, vision, hearing, breathing, sleeping, eating, speech, excretion, usual activities, mental function, discomfort and symptoms, depression, distress, vitality and sexual activity). All dimensions have five possible response options ranging from 1 (best possible) to 5 (worst possible). The single index score (15D score) and the dimension level values are calculated from the health state descriptive system (questionnaire) by using a set of population-based preference or utility weights [Citation10]. The minimal clinically important difference (MID) of the 15D score has been estimated as 0.015 [Citation11].

The EQ-5D-3L consists of five dimensions (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, anxiety/depression) divided into three levels reflecting the severity of problems (no, some, severe problems). The EQ-5D-3L can describe 243 different health states and is currently probably the most widely used HRQoL instrument. We used the most commonly used valuation system of the EQ-5D-3L, the British time trade-off-based ‘tariff’, which produces utility scores ranging from –0.59 to 1 (1 = full health, 0 = death, –0.59 = worst possible health). The MID of the EQ-5D is approximately 0.08 [Citation12].

The EQ-5D-3L also includes a visual analog scale where a patient is asked to rate his/her current health state from 0 to 100, where 100 indicates the best imaginable health state and 0 the worst imaginable health state.

The EORTC-QLQ-C30 is a 30-item cancer-specific HRQoL instrument and produces a global health status, five functioning scales (physical, role, social, emotional, cognitive functions) and three symptom scales (fatigue, nausea/vomiting, pain) and six single-symptom items (dyspnea, insomnia, appetite loss, constipation, diarrhea, financial difficulties) [Citation13]. The degree to which cancer caused financial problems was based on the EORTC-QLQ-C30 question about perceived financial difficulties: ‘Has your physical condition or medical treatment caused you financial difficulties?’ It was used to divide the patients into four groups according to the answer to this question. The groups were Not at All (FD0), A Little (FD1), Quite a Bit (FD2) and Very Much (FD3).

Statistical analysis

The descriptive analysis was done based on patients’ disease state and level of financial difficulties. We calculated the total OOP payments and the total healthcare costs per disease state during the preceding six-month period. The differences in mean costs are reported using 95% confidence intervals. We also calculated the components of OOP payments in different groups of financial difficulties and assessed the mean HRQoL scores (15D and EQ-5D-3L) and the mean 15D profiles for the groups. The other FD groups were compared to FD0 group using t-test.

To examine the associations between sociodemographic and cancer-related variables, financial difficulties and HRQoL, we hypothesized a path model with two endogenous variables (financial difficulties and HRQoL), and a set of exogenous explanatory variables including age, high education, employment status, marital status, type of work (white collar/blue collar), total direct health care costs, OOP payments, along with the disease states for three cancer types, and comorbidity. Comorbidity was defined as a patient being eligible for higher drug reimbursement due to at least two other chronic conditions. This information was available from the SII registries. Financial difficulties were introduced as an endogenous variable, as there is earlier evidence on a strong direct negative association of financial difficulties with HRQoL [Citation5,Citation14,Citation15].

The endogenous status of financial difficulties is based on an assumption that exogenous variables may be directly associated with HRQoL, but also with financial difficulties, associating thus indirectly through financial difficulties with HRQoL. To estimate the path coefficients (standardized beta coefficients) for the path model, two stepwise linear regression models were run, one for each endogenous variable, with the exogenous variables as potential explanatory variables plus financial difficulties for the 15D score. The indirect effect of an explanatory variable on the 15D score was calculated by multiplying the direct effect of the variable by the direct effect of financial difficulties on the 15D score. The total effect of a variable on the 15D score via financial difficulties was calculated by summing the direct and indirect effect.

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 22 (Statistical Package for Social Sciences) (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) with an alpha level of 5%. The study is a cross-sectional registry and survey study and was approved by the local Ethics Committee.

Results

Patient characteristics

Altogether 1978 patients were recruited for this study and of them, 54.2% were male (). The median age of the patients was 66 years and ranged from 26 to 96 years. Fifty-four percent of the patients had higher education meaning that they had been educated for more than 12 years. The majority of the patients were retired (63%), 27% were employed and 4% unemployed or not working. Half of the patients were classified as white-collar workers and the majority of them were married or cohabiting (66%) (). Patients were divided into five groups based on their disease state: 226 were in primary treatments, 387 in the rehabilitation state, 916 in the remission state, 375 in the metastatic state and 74 in palliative care. Out of all patients who completed the questionnaire 79.1% reported not at all, 14.2% a little, 4.7% quite a bit and 2.0% very much health-related financial difficulties.

Table 1. Patient characteristics.

In the group that reported very much health-related financial difficulties, the majority were men (78.9%), living alone (55.3%) and unemployed (84.2%). Almost half of the patients were in the remission state of the disease (47.4%).

Cost analysis

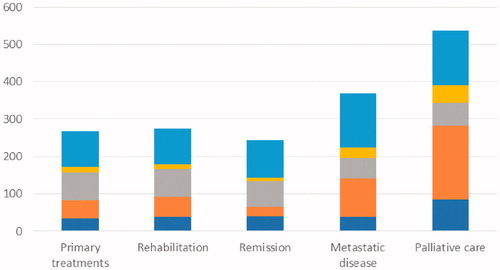

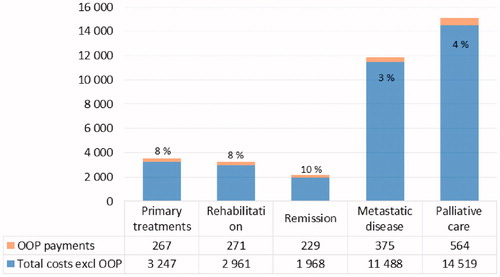

During the 6-month period, OOP payments were highest in the palliative care group (€603) compared to the metastatic state (€383), remission (€224), rehabilitation (€264) and primary treatment (€263) groups. OOP payments were proportionally highest in the remission group (). The highest mean OOP payments were for medication (€110) and the lowest for travel (€15). The range of total OOP payments was from 0 to 2901 euros. Travel fees, outpatient medication fees, primary healthcare fees and specialist care fees were highest in the palliative care group. Outpatient medication fees and specialist care fees were both over 30% of the total OOP payments in the palliative care group ().

Figure 1. Patient out-of-pocket (OOP) and total costs according to disease state (6-month time, €). The percentage figures indicate the proportion of out-of-pocket payments out of the total costs.

Mean OOP payments were the higher the more a person reported financial difficulties (FD0: €245, FD1: €379, FD2: €396 and FD3: €429). The FD3 group had the highest mean OOP payments for medication, primary healthcare and specialist care compared to other groups.

The share of private healthcare costs was over 20% for primary treatments, rehabilitation and remission states whereas in the metastatic state it was approximately 12% and in the palliative care group only 6%.

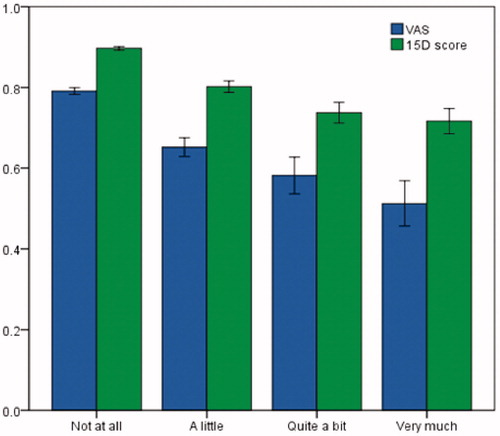

Health-related quality of life

The mean utility values varied depending on the instrument used. The mean 15D, EQ-5D-3L and VAS scores in the group that reported no financial difficulties were 0.896, 0.872 and 79.1, respectively. In the group that reported a lot of financial difficulties, the mean 15D, EQ-5D and VAS scores were 0.714, 0.451 and 49.9, respectively. The mean utility scores were, irrespective of the HRQoL instrument used, the lowest in the group that reported a lot of financial difficulties (). Compared to the group that reported no financial difficulties, the differences were statistically significant (p < .001) and clinically important.

Figure 3. Mean utility scores (15D and VAS*) in different financial difficulties groups (error bars: 95% confidence intervals). *VAS scores were divided by 100.

The decreasing trend in the utility values from FD0 to FD3 was also seen on all of the 15D dimensions and the differences between FD0 and FD3 were statistically significant except for ‘eating’ and ‘speech’ (). The largest difference in the utility values between the FD0 and FD3 groups was seen in ‘usual activities’, where FD0 obtained a mean value of 0.903 and FD3 a mean value of 0.558, respectively. The EORTC QLQ-C30 functioning scales were significantly lower in the FD3 group compared to the FD0 group, the biggest difference being in role functioning. All symptoms measured by the EORTC QLQ-C30 were statistically significantly more common in the FD3 group than in the FD0 group. The highest differences were reported in fatigue, pain and insomnia.

Path model

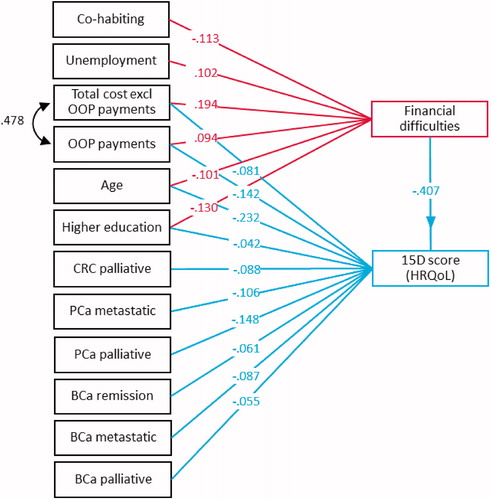

The path model with direct effects is shown visually in and the results of the path model with direct, indirect and total effects in . Factors that attenuated (direct negative association) financial difficulties in a statistically significant manner were age, cohabiting and higher education. Factors that increased (direct positive association) financial difficulties were OOP payments, higher total healthcare costs and unemployment. Factors that associated directly negatively with HRQoL were age, OOP payments, public healthcare costs, financial difficulties and the more serious disease states of all cancer types. High education was directly positively associated with HRQoL. Financial difficulties, age, OOP payments and total healthcare costs had the highest negative and high education highest positive total effect on HRQoL. The cancer states, even the serious ones were not statistically significantly associated with financial difficulties ( and ).

Figure 5. HRQoL – financial difficulties path model with correlations. Model indicates the direct and indirect effects of socioeconomic and clinical factors on financial difficulties and the 15D score and the total effect of financial difficulties on the 15D score. Red lines present the association of a single explanatory variable to Financial difficulties and blue lines the association to 15D (HRQoL). Standardized coefficients from linear regression models were used. Arrow between total costs excluding OOP payments and OOP payments indicates correlation coefficient of 0.478.

Table 2. The results of the path model for financial difficulties and HRQoL.

Discussion

OOP payments are an important factor to take into consideration among chronically ill patients, especially in cancer patients. In the USA, Medicare beneficiaries with cancer were reported to face higher OOP payments than their counterparts without cancer [Citation16,Citation17] and OOP payments caused a significant burden for cancer patients [Citation18]. In our study, the highest OOP payments were for medication. In a study among glioma patients in the USA, highest mean OOP payments were for medication, transportation and hospital bills [Citation19]. In our study, the secondary health care OOP payments were in a smaller role. In addition to medical costs, OOP payments are caused by nonmedical costs such as transportation and lost wages. A study in Haiti showed that despite receiving free breast cancer care, the majority of patients faced catastrophic medical expenses [Citation20].

High OOP payments can lead to financial difficulties and impaired quality of life. The financial burden is an important factor when analyzing the effects of OOP payments because it can cause patients to delay seeking care and to forgo necessary treatments. OOP payments can affect treatment decisions and patient compliance [Citation21]. A high financial burden has been reported among people with low income, low education, women and people with poor health [Citation22]. In our study, patients who reported very much health-related financial difficulties were more likely to be men, living alone or unemployed.

We found that financial difficulties, age, high total health care costs and OPP payments had the most significant total negative effect on HRQoL among cancer patients. In line with previous studies, financial difficulties had also in our study the largest negative direct and total effect on HRQoL. In a US study, financial difficulties had a clear negative effect on cancer patients HRQoL and the degree to which cancer caused financial difficulties was the strongest independent predictor of HRQoL [Citation4]. A recent study from Ireland among breast and prostate cancer patients reported that pre-diagnosis employment status and financial circumstances were important predictors of post-diagnosis wellbeing [Citation23].

It is important to identify the factors that are related to financial difficulties. In a Norwegian study among head and neck cancer patients, there was no significant increase in financial difficulties during the initial treatment period [Citation24]. In Nordic countries, most of cancer treatment costs are funded by tax revenues. Therefore, it seemed reasonable to presume that in Finland cancer treatments would not cause a major financial burden either. However, according to our results, the use of healthcare services is associated with the accumulation of substantial OOP payments. In our study, OOP payments were one of the major factors that increased financial difficulties together with the heavy use of cancer or other expensive treatments and unemployment.

Surprisingly, patients in the palliative care group had the highest mean OOP payments. To our knowledge, this has not been reported before. Compared to other disease states, highest OOP payments were related to outpatient medication, traveling, primary healthcare and specialist care. According to our results, OOP payments can be an important contributing factor to the impaired HRQoL among patients in the palliative state. According to our study, patients with end-stage disease, especially when they have socio-economic problems, could benefit most from social and economic support.

There are some limitations to our study. Due to the cross-sectional nature of the study, we could not estimate the long-term effects of the OOP payments on HRQoL. Also, the group of palliative patients was small compared to other disease state groups. Whether the results are generalizable to other countries with lower OOP payments, also remains to be determined in future studies.

Conclusions

According to our results, OOP payments are related to financial difficulties which have a significant negative effect on HRQoL. This is especially a concern in Finland where the proportion of OOP payments of the total healthcare costs is high compared to other developed countries. In our study, the most worrying group was the palliative care group as it had the highest mean public healthcare cost and OOP payments and worst HRQoL.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Zafar SY, Peppercorn JM, Schrag D, et al. The financial toxicity of cancer treatment: a pilot study assessing out-of-pocket expenses and the insured cancer patient's experience. Oncologist. 2013;18:381–390.

- Ballester-Arnal R, Gomez-Martinez S, Fumaz CR, et al. A Spanish study on psychological predictors of quality of life in people with HIV. AIDS Behav. 2016;20:281–291.

- Delgado-Guay M, Ferrer J, Rieber AG, et al. Financial distress and its associations with physical and emotional symptoms and quality of life among advanced cancer patients. Oncologist. 2015;20:1092–1098.

- Fenn KM, Evans SB, McCorkle R, et al. Impact of financial burden of cancer on survivors' quality of life. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10:332–338.

- Torvinen S, Farkkila N, Sintonen H, et al. Health-related quality of life in prostate cancer. Acta Oncol (Stockholm, Sweden). 2013;52:1094–1101.

- Ubel PA, Abernethy AP, Zafar SY. Full disclosure-out-of-pocket costs as side effects. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1484–1486.

- Farkkila N, Torvinen S, Sintonen H, et al. Costs of colorectal cancer in different states of the disease. Acta Oncol (Stockholm, Sweden). 2015;54:454–462.

- Torvinen S, Farkkila N, Roine RP, et al. Costs in different states of prostate cancer. Acta Oncol. 2016;55:30–37.

- Farkkila N, Sintonen H, Saarto T, et al. Health-related quality of life in colorectal cancer. Colorectal Dis. 2013;15:e215–e222.

- Sintonen H. The 15D instrument of health-related quality of life: properties and applications. Ann Med. 2001;33:328–336.

- Alanne S, Roine RP, Rasanen P, et al. Estimating the minimum important change in the 15D scores. Qual Life Res. 2015;24:599–606.

- Pickard AS, Neary MP, Cella D. Estimation of minimally important differences in EQ-5D utility and VAS scores in cancer. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2007;5:70.

- Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:365–376.

- Perrone F, Jommi C, Di Maio M, et al. The association of financial difficulties with clinical outcomes in cancer patients: secondary analysis of 16 academic prospective clinical trials conducted in Italy. Ann Oncol. 2016;27:2224–2229.

- Nobre N, Pereira M, Roine RP, et al. Factors associated with the quality of life of people living with HIV in Finland. AIDS Care. 2017;29:1074–1078.

- Davidoff AJ, Erten M, Shaffer T, et al. Out-of-pocket health care expenditure burden for Medicare beneficiaries with cancer. Cancer. 2013;119:1257–1265.

- Bernard DS, Farr SL, Fang Z. National estimates of out-of-pocket health care expenditure burdens among nonelderly adults with cancer: 2001 to 2008. JCO. 2011;29:2821–2826.

- Pisu M, Azuero A, McNees P, et al. The out of pocket cost of breast cancer survivors: a review. J Cancer Surviv. 2010;4:202–209.

- Kumthekar P, Stell BV, Jacobs DI, et al. Financial burden experienced by patients undergoing treatment for malignant gliomas. Neurooncol Pract. 2014;1:71–76.

- O'Neill KM, Mandigo M, Pyda J, et al. Out-of-pocket expenses incurred by patients obtaining free breast cancer care in Haiti. Lancet. 2015;158:747–755.

- Neumann PJ, Palmer JA, Nadler E, et al. Cancer therapy costs influence treatment: a national survey of oncologists. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29:196–202.

- Bremer P. Forgone care and financial burden due to out-of-pocket payments within the German health care system. Health Econ Rev. 2014;4:36.

- Sharp L, Timmons A. Pre-diagnosis employment status and financial circumstances predict cancer-related financial stress and strain among breast and prostate cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24:699–709.

- Egestad H, Nieder C. Undesirable financial effects of head and neck cancer radiotherapy during the initial treatment period. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2015;74:26686.