Abstract

Purpose: Lymphoma survivors after high dose therapy with autologous stem cell therapy (HD-ASCT) are at high risk for late adverse effects (AEs). Information patients receive and collect throughout their cancer trajectory about diagnosis, treatment schedule and risks of AEs may influence attitudes and health-related behavior in the years after treatment. The purpose of this study was to explore level of knowledge in lymphoma survivors after HD-ASCT at a median of 12 years after primary diagnosis.

Material and methods: From a national study on the effects of HD-ASCT for lymphomas, 269 survivors met for an outpatient examination, including a structured interview addressing knowledge about diagnosis and treatment. Survivors were also asked whether they knew and/or had experienced certain common late AEs. Numbers of recognized and experienced late AEs were presented as sum scores. Factors associated with the level of knowledge of late AEs were analyzed by linear regression analysis.

Results: Eighty-one percent of the survivors knew their diagnosis, 99% knew the components of HD-ASCT and 97% correctly recalled having had radiotherapy. Ninety percent reported awareness of late AEs, but the level of knowledge and personal experience with specified AEs varied. Thirty-five percent of survivors stated to have received follow-up for late AEs. In multivariable analysis younger age at diagnosis, having received mediastinal radiotherapy, higher mental health related quality of life, a higher number of self-experienced late AEs and having received follow-up care for late AEs were significantly associated with a higher level of knowledge of AEs.

Conclusion: The majority of lymphoma survivors treated with HD-ASCT correctly recalled diagnosis and treatment, while knowledge of late AEs varied. Our findings point to information deficits in survivors at older age and with lower mental health related quality of life. They indicate benefit of follow-up to enhance education on late AEs in lymphoma survivors.

Introduction

In Norway, malignant lymphomas collectively represent the eighth most common malignancy, but are overrepresented among cancers diagnosed in childhood, adolescence and younger adulthood [Citation1]. Advances in chemotherapy and radiotherapy during the last decades have substantially increased the prevalence of lymphoma survivors [Citation1]. Curative lymphoma treatment is often highly toxic, and survivors carry a risk of acute and late adverse effects (AEs) of treatment [Citation2,Citation3]. Possible late AEs include secondary cancers, cardiovascular disease, peripheral neuropathies, hormonal disturbances, infertility, chronic fatigue (CF) and mental distress. Some may result in increased mortality, others might impair health relate quality of life (HRQoL), social functioning and work ability [Citation2–4].

For certain groups of lymphoma patients, therapy of primary or relapsed/refractory disease involves high dose treatment with autologous stem cell transplantation (HD-ASCT) given as consolidation after one or more lines of conventional systemic therapy [Citation5]. The procedure includes an intensive conditioning chemotherapy regimen, sometimes combined with total body irradiation. Many survivors of HD-ASCT will also have received one or more series of local radiotherapy before or after the transplantation that will increase their risk of late AEs in the years to follow [Citation2,Citation3].

Given the complexity and risk of the HD-ASCT, adequate counselling of patients before and in the years after treatments is pertinent. Information can reduce survivors’ mental distress, increase sense of responsibility for their own health and motivate a healthy lifestyle [Citation6,Citation7]. Knowledge of personal risk may lead to participation in follow-up and empower survivors in facing health care providers and their social environment.

Most studies on survivors’ perception of their diagnosis and treatment, possible sequelae and follow-up been done on survivors of childhood cancers [Citation6–11]. Of note, survivors treated at young age have a long life-span to develop late AEs, representing a challenge for continuous patient education [Citation12,Citation13]. We and others have identified knowledge deficits in survivors, especially regarding late AEs of treatment, in longitudinal studies, knowledge may decrease with time [Citation11]. Attendance in survivorship clinics has been suggested to improve the ability to learn about risks of late AEs. Fewer studies exist on survivors of cancer in adolescence or adulthood [Citation14,Citation15]. Despite similarities to survivors of childhood cancer concerning burden of potential late AEs during a post-treatment life span, studies of knowledge in survivors of HD-ASCT have not been done.

The primary aim of the present study was to investigate knowledge concerning diagnosis, treatment, late AEs and follow-up in adult lymphoma survivors treated with HD-ASCT. Second, we wanted to examine factors associated with the level of knowledge of late AEs. Through this we aim to better understand and possibly improve information strategies and follow-up concerning late AEs after HD-ASCT.

Material and methods

Participants

Lymphoma survivors aged ≥18 years, treated with HD-ASCT in Norway between 1987 and 2008, and alive as per 31 December 2011, were eligible for this cross-sectional study performed in 2012/2013, as described in detail previously [Citation4,Citation16]. Among 407 eligible survivors, 1 was excluded due to emigration, 4 due to current systemic therapy for active malignancies and 3 due to lack of official home address, leaving 399 survivors invited by mail. Of these, 269 (67% response rate) attended an out-patient clinical examination in one of the four participating university hospitals. The survey included a comprehensive questionnaire (with patient reported outcome measures) and a structured interview with a nurse or doctor covering knowledge on diagnosis, treatment as well as potential and self-experienced late AEs and follow-up (Supplementary Table 1).

Table 1. Survivor characteristics according to level of knowledge about late adverse effects (N = 269).

Lymphomas and treatment

Based on the primary diagnosis, three groups of lymphomas were defined: Hodgkin’s lymphoma, aggressive (including diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, mantle cell lymphoma, Burkitt’s lymphoma, lymphoblastic lymphoma and T-cell lymphomas) and indolent (mostly follicular lymphoma) non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Treatment for lymphomas in Norway followed national and international guidelines [Citation5,Citation17]. The high-dose regimen consisted of total body irradiation and high dose cyclophosphamide from 1987 to 1996, replaced by BEAM chemotherapy (Carmustine, Etoposide, Cytarabin and Melphalan) from 1996 [Citation5]. Details on lymphoma-related variables were retrieved from medical records.

The information concerning the procedure of HD-ASCT and risk of late AEs has over the years been structured in all four Norwegian transplantation centers with designated pretreatment information visits with the patient, an oncologist and a nurse. Written information has uniformly been provided to the patient. After the HD-ACST, survivors are generally followed by an oncology or hematology unit for 5 years, thereafter once annually by their general practitioner [Citation17]. The content of follow-up varies with the underlying diagnosis, complexity of treatment, age, gender and other individual factors [Citation17].

Outcome variables

The structured study interview focused on survivors’ knowledge of diagnosis, treatment, late AEs and follow-up. The questions were developed by our group for a previous study on adult survivors of childhood lymphoma [Citation10] and modified for the purpose of the present survey. For questions on diagnosis, treatment, late AEs and follow-up, the response alternatives were ‘yes’, ‘no’ or ‘do not know’. The latter response alternatives were grouped as ‘no’ for analyses. Concerning individual late AEs, five were specified (reduced fertility, hormonal changes, cardiovascular disease, CF and secondary cancer) as well as one additional category ‘other’ (late AEs) open for detailing by the respondent. The question on late AEs included the response category ‘personal experience’ in addition to the response alternatives mentioned above. The level of knowledge about late AEs was scored by the number of detailed late AEs known by the survivor (‘yes’ category), ranging from 0 to 6. Similarly, the burden of self-experienced late AEs was the sum of responses on ‘personal experience’. Missing responses were below 1% for all questions and they were excluded from the analysis.

Questionnaires

The Short Form-36 (SF-36) contained scores on eight dimensions (four physical and four mental) of generic HRQoL [Citation18]. All dimensional scores were converted from 0 to 100 with higher scores representing better HRQoL. The physical and mental composite scales were calculated by T-transformations, and the mean score were 50 and the standard deviation (SD) 10 based on Norwegian population data [Citation19]. The SF-36 scale is considered a reliable and valid assessment of self-reported HRQoL [Citation20].

CF was assessed by the Fatigue Questionnaire (FQ) [Citation21]. The FQ covered the last 4 weeks and contained 11 items covering mental and physical fatigue that were added up to a total fatigue score. Each item had four response alternatives scored 0–3. Higher sum scores represented more fatigue. One additional question assessed the duration of fatigue. In order to calculate the prevalence of CF the responses on each of the 11 FQ items were dichotomized (0 and 1 scored as 0, and 2 and 3 scored as 1) [Citation22]. CF was defined as a sum score ≥4 of the dichotomized responses with duration of >6 months. The internal consistency was Cronbach’s coefficient alpha of 0.92 for total fatigue.

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) concerned anxiety and depressive symptoms last week and consisted of seven items for each of the two sub-scales [Citation23]. The item scores ranged from 0 (not present) to 3 (highly present), so the sub-scale scores ranged from 0 (low) to 21 (high) with higher scores indicating more symptoms [Citation23]. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.82 and 0.87 for the depression and anxiety subscales, respectively.

Socio-demographic, health and lifestyle variables

Paired relationship was defined as being married or cohabiting. Level of education was dichotomized into low (≤12 years of education) and high (>12 years). Work status was dichotomized as either being in paid work (or currently on sick leave) or no paid work (on disability pension or retirement pension, on social support while seeking work, homemakers or students). Cardiovascular disease was present if the survivors reported one or more of stroke, transient ischemic attack, myocardial infarction, angina pectoris, heart failure or hypertension. Memory or concentration problems were based on two items ‘Do you have problems remembering things?’ and ‘Have you had problems concentrating, e.g., reading the newspaper or watching TV?’ [Citation24]. Both items had four response alternatives and the ratings ‘quite much’ or ‘very much’ on one of the items were considered as problem present. Physical activity was examined according to World Health Organization’s recommendations. The general recommendation was ≥150 min of moderate intensity or ≥75 min of high intensity exercise per week [Citation25]. Results were dichotomized into ‘followed’ or ‘did not follow’ recommendations. Smoking concerned current, daily or occasional consumption of any number of cigarettes. Obesity was defined as body mass index ≥30 kg/m2.

Statistical analyses

Categorical variables for groups of survivors were presented as numbers and percentages and compared with the chi-square test. For continuous variables, mean and standard deviation (SD) are presented and comparisons done with the unrelated sample t-test. In case of skewed distributions, Mann-Whitney U-tests were used. Internal consistencies of the instruments were examined with Cronbach’s coefficient alpha. To identify characteristics associated with the level of knowledge of late AEs we conducted univariate and multivariable linear regression modeling using the number of known late AEs (range 0–6) as the dependent variable. In addition to gender, variables identified in the initial analysis or otherwise believed to be important for the level of knowledge were entered the model. These were age at diagnosis, time from diagnosis to survey, having received mediastinal radiotherapy, the mental and physical HRQoL, the number of late AEs experienced and having received follow-up for late AEs. Other variables concerning age and time (such as age at survey and time from HD-ASCT to survey), the use of radiotherapy at any site (including total body irradiation) and other measures of mental distress (HADS_D) were excluded because of multicollinearity. The strength of associations in both univariate and multivariable regression was expressed as regression coefficients B with 95% confidence intervals. All tests were two-sided and p-values below .05 were considered significant. International Business Machines (IBM) Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 23 for PC (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) was used for all analyses.

Ethics

The Regional Committee for Medicine and Health Research Ethics of South-East Norway approved the study (2011/1353B). All participants gave written informed consent.

Results

Attrition analysis

There were no significant differences between participants (N = 269) and non-participants (N = 120) regarding gender, age at survey, age at diagnosis, age at HD-ASCT or time from HD-ASCT to survey (data not shown).

Patient characteristics

The characteristics of responding survivors are shown in . The median age at diagnosis was 42 years (range 10–65), the median age at survey was 56 years (range 24–77). The median time from primary diagnosis to survey was 12 years (range 3–34) and the median time from HD-ASCT was 9 years (range 3–25).

Table 2. Associations between survivor characteristics and knowledge level of late adverse effects (N = 251)a.

Knowledge of diagnosis and treatment

In total, 81% of survivors recalled correctly the type of lymphoma they were treated for, 7% gave a wrong answer and 12% did not remember. Regarding the conditioning regimen, 99% differentiated correctly having received chemotherapy only, or total body irradiation and chemotherapy. In total, 64% of survivors answered that they had received radiotherapy (including total body irradiation) at any time point of their lymphoma history, and for 97% of these the answer was correct. Of the survivors that had received mediastinal radiotherapy, 92% identified having received radiotherapy. Only 13% of the participants remembered having received written information on diagnosis and treatment.

Knowledge and experience with late AEs

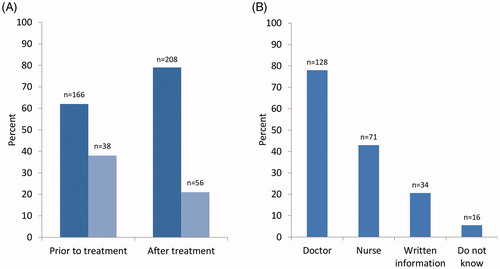

Responses regarding knowledge of late AEs after HD-ASCT and recalled sources of information are depicted in . In total, 90% of the survivors reported being aware of late AEs, having received information either prior to HD-ASCT (62%) and/or become aware of the risk after (79%) (). Of those informed prior to HD-ASCT, 78% identified a doctor as a source of information (). Of those that had become aware of late AEs after treatment, 79% included ‘personal experience’ as a source of information, 52% recalled having been informed by their oncologist and 8% by their general practitioner. Thirty-five percent reported having received follow-up for potential or self-experienced late AEs by their general practitioner or in hospital.

Figure 1. Responses on recalled time and source of information on late AEs after HD-ASCT. (A) Survivors recalling information before or after HD-ASCT. Dark blue signifies 'yes' and light blue 'no/do not know'. (B) Survivors recalling different sources of information. AE: adverse effect, HD-ASCT: high dose therapy with autologous stem cell transplantation.

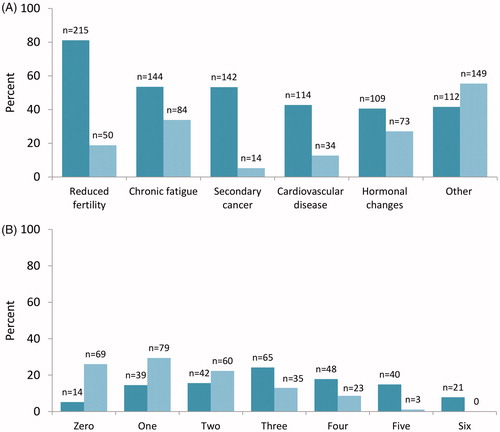

Details about survivors’ level of knowledge and personal experience with different late AEs after HD-ASCT are depicted in . Between 41% and 81% of survivors knew that HD-ASCT could be associated with any of the five specified AEs, with reduced fertility being most frequently recalled (). Forty-two percent of survivors listed knowledge of other AEs, commonly muscular pain, neuropathy and dental problems. Between 5% and 34% of survivors stated personal experience with the specified late AEs, the most common being CF. Fifty-five percent listed experiences with ‘other’ late AEs (). The number of AEs recalled and/or experienced by each survivor is provided in . Forty-one percent of survivors had knowledge of ≥4 late AEs, while 10% had experience with ≥4 AEs. Twenty-six percent reported no experience with any AE.

Figure 2. Knowledge of and experience with different late adverse effects. (A) Survivors recognizing (dark turquoise) or stating personal experience with (light turquoise) each late AE. (B) Survivors with knowledge (dark turquoise) or personal experience (ligh turquoise) with different numbers of late AEs. AE: adverse effect.

Factors associated with the level of knowledge of late AEs

When grouped according to the number of recognized late AEs, survivors that recalled 0–3 (60% of respondents) or 4–6 (40%) relevant conditions differed in several sociodemographic and treatment-related factors (). Survivors with a higher level of knowledge were significantly younger at diagnosis and survey. They were more likely to have received total body irradiation, mediastinal radiotherapy or radiotherapy in general and had a lower physical HRQoL. These survivors had a higher education level and reported a higher number of experienced late AEs and more frequent follow-up for late AEs.

In sub-analyses (data not shown), the proportion of survivors recognizing cardiovascular disease as a late AE was higher in the group treated with mediastinal radiotherapy than in patients without (54 vs 46%, p = .005). Furthermore, 66% reported knowledge of secondary cancer after mediastinal radiotherapy versus 45% in the group without (p = .001). Among survivors that fulfilled the criteria for CF by responses in the FQ (n = 85), only 64% reported knowledge of this specific AE in the interview.

Results of the multivariable linear regression analyses for independent factors associated with the level of knowledge of late AEs are depicted in . When excluding variables showing multicollinearity, the final multivariable model included 251 patients. Residual statistics confirmed the assumptions of linearity, normality and homoscedasticity (data not shown). In the multivariable regression analysis, younger age at diagnosis, higher mental HRQoL, having received mediastinal radiotherapy, more experience with late AEs and having received follow-up for late AEs were significantly associated with a higher level of knowledge ().

Discussion

Norwegian long-term survivors of HD-ASCT for lymphoma in adulthood have good knowledge of their diagnosis and treatment, but variable knowledge of late AEs. Whereas most of survivors recognized reduced fertility as being associated with HD-ASCT, secondary cancers and cardiovascular disease as late AEs were known to about half of survivors or less. In multivariable analysis younger age at diagnosis, higher mental HRQoL, having received mediastinal radiotherapy, having more experience with late AEs and having received follow-up for late AEs were associated with a higher knowledge level of late AEs.

Our group has previously conducted a similar interview-based study in survivors after lymphoma in childhood and adolescence, treated between 1970 and 2000 [Citation10]. Whereas a large majority of these survivors correctly identified their diagnosis and essential components of treatment, 66% were not aware of any risks for late AEs, similar to the low level of awareness reported by others for survivors of cancers in childhood. In contrast, 41% of survivors after HD-ASCT in our cohort recognized ≥4 late AEs and 90% reported to be aware of the risk of late AEs in general. Although not directly comparable, the improved awareness seen in our study might be explained by age at treatment. Children with cancer are often not directly informed and relevant information is instead provided to their parents [Citation7]. Furthermore, our adult survivors of HD-ASCT were treated after 1987, and focus on cancer survivorship and late AEs have improved over the last decades [Citation26]. Additionally, the detailed information supplied to patients scheduled to undergo HD-ASCT might have provided them with more knowledge.

Within our cohort of survivors, we found a significant association between a higher level of knowledge and younger age at diagnosis. A Danish study from 2013 [Citation27], described how cancer patients in young adulthood are more dissatisfied with information and support at diagnosis and during treatment. This might be due to the higher impact a cancer diagnosis has at a younger age. Furthermore, younger patients often take a more active role in seeking information [Citation27]. Consequently, high demands and an active pursuit of information can explain the observed association between high knowledge of late AEs and younger age in our study. The association with age was particularly noticeable when asked about fertility with survivors aware of the risk of reduced fertility being significantly younger that those unaware of this risk (39 vs 52 years; p < .001). The importance of communicating this risk both prior to and after treatment has been highlighted in international guidelines, as a pivotal example of how proper information can aid personal decision making [Citation28]. The reverse association of less knowledge of late AEs in the elderly population should prompt health care providers to focus on education of elderly survivors.

In our study, a high mental HRQoL was significantly and positively associated with the level of knowledge of late AEs. Substituting the SF-36 mental composite score with respondents’ HADS_D scores gave identical results (data not shown). The association of mental distress and level of knowledge may have different explanations. Low mental HRQoL may hamper information uptake and management as it is believed to negatively affect memory and concentration [Citation29]. Additionally, the reverse association is hypothesized; lack of information can lead to insecurity and mental distress such as depression and anxiety [Citation6,Citation30]. A practical consequence of this finding may be the need to secure adequate information especially to patients presenting with mental distress at diagnosis and follow-up.

We found that participation in follow-up for late AEs was associated with a higher level of knowledge in survivors of HD-ASCT. Studies have shown that survivors of childhood cancer who attend long-term follow-up have more knowledge of late AEs [Citation11] and fewer visits to the emergency room [Citation31]. In our study only about one-third of survivors had attended follow-up for late AEs at some point after HD-ASCT. The lack of follow-up replicates findings in long-term survivors of childhood cancers, where the majority of both survivors and family members reported unmet information needs and follow-up [Citation7,Citation9].

Since radiotherapy is associated with an increased risk of serious late AEs, most notable cardiovascular disease and secondary cancers [Citation2,Citation16], there has been emphasis on information to lymphoma survivors of radiotherapy. Accordingly, written information concerning these risks was provided to all Norwegian general practitioners in 2010 and a leaflet was distributed retrospectively in 2012 to all Norwegian lymphoma survivors after irradiation to the neck and thorax [Citation32]. It is thus reassuring to find that having received mediastinal radiotherapy is associated with a higher level of knowledge of late AEs in general multivariable analysis and with the risk of secondary cancer and cardiovascular disease in univariate analysis. These observations suggest that repeated updates on long-term risks of late AEs disseminated to both general practitioners and survivors may be beneficial.

Of interest, we observed a discrepancy between survivors’ symptoms of CF and their knowledge of fatigue as a relevant late AE in the structured interview. Thirty-six percent of survivors with CF did not recognize this condition as an established late AE. Lack of knowledge might have implications for how the survivors, their health care providers and social environment adapt to CF. Psychoeducation and balanced physical activity are recommended strategies for CF in cancer survivors [Citation33]. It seems likely that acknowledgment of CF as an outcome after treatment is a prerequisite for coping and better care for fatigued survivors.

We found the number of experienced late AEs to be associated with the level of knowledge in multivariable analysis, indicating that patients embrace information best when symptoms emerge. Late AEs often arise years to decades after treatment when survivors have left specialist follow-up. Therefore, how to provide survivorship care and relevant information in a structured manner over time is widely debated [Citation26,Citation34]. Our findings represent incentives to further strengthen the education of general practitioners on cancer survivors needs and to provide repeated information to survivors over prolonged timeframes.

To our knowledge, this is the first study of lymphoma survivors’ awareness of their personal lymphoma history and possible late AEs after HD-ASCT. This high-risk group of survivors, most of whom had also received radiotherapy, provides an opportunity for learning from existing structures of follow-up. Our findings suggest improving health care for these survivors, especially the elderly and survivors with mental distress and CF. Our study is a nationwide follow-up survey with a high participation rate and no clear attrition bias. Presumably, our findings can therefore be extrapolated to lymphoma survivors after HD-ASCT in general. The study is limited by its’ retrospective and cross-sectional design. Responses were collected in a structured interview and not through a validated questionnaire. The data was collected in 2012/2013 and awareness of late AEs may have changed in the years since the study was performed.

In conclusion, the results of the present study may inspire health care personnel; both in specialist and primary care, to focus more on providing relevant and timely information on late AEs to survivors of HD-ASCT at treatment and follow-up. Further research should aim to define how, when and in what format information should be given.

Supplemental Material

Download (33.8 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Cancer in Norway 2017 – cancer incidence, mortality and prevalence in Norway. Cancer registry of Norway, 2018. [cited 2019 Jun 21]. Available from: https://www.kreftregisteret.no/Generelt/Rapporter/Cancer-in-Norway/cancer-in-norway-2017/

- Van Leeuwen FE, Ng AK. Long-term risk of second malignancy and cardiovascular disease after Hodgkin lymphoma treatment. Hematol Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2016;2016:323–330.

- Majhail NS, Ness KK, Burns LJ, et al. Late effects in survivors of Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma treated with autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation: a report from the bone marrow transplant survivor study. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2007;13:1153–1159.

- Bersvendsen HS, Haugnes HS, Fagerli UM, et al. Lifestyle behavior among lymphoma survivors after high-dose therapy with autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, assessed by patient-reported outcomes. Acta Oncol 2019;58:690–699.

- Smeland KB, Kiserud CE, Lauritzsen GF, et al. High-dose therapy with autologous stem cell support for lymphoma in Norway 1987-2008. Tidsskriftet. 2013;133:1704–1709.

- Gianinazzi ME, Essig S, Rueegg CS, et al. Information provision and information needs in adult survivors of childhood cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2014;61:312–318.

- Vetsch J, Fardell JE, Wakefield CE, et al. “Forewarned and forearmed”: long-term childhood cancer survivors' and parents' information needs and implications for survivorship models of care. Patient Educ Couns. 2017;100:355–363.

- DeRouen MC, Smith AW, Tao L, et al. Cancer-related information needs and cancer's impact on control over life influence health-related quality of life among adolescents and young adults with cancer. Psychooncology. 2015;24:1104–1115.

- Lie HC, Loge JH, Fossa SD, et al. Providing information about late effects after childhood cancer: lymphoma survivors' preferences for what, how and when. Patient Educ Couns. 2015;98:604–611.

- Hess SL, Johannsdottir IM, Hamre H, et al. Adult survivors of childhood malignant lymphoma are not aware of their risk of late effects. Acta Oncol. 2011;50:653–659.

- Lindell RB, Koh SJ, Alvarez JM, et al. Knowledge of diagnosis, treatment history, and risk of late effects among childhood cancer survivors and parents: the impact of a survivorship clinic. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62:1444–1451.

- Hudson MM, Ness KK, Gurney JG, et al. Clinical ascertainment of health outcomes among adults treated for childhood cancer. JAMA. 2013;309:2371–2381.

- Armstrong GT, Liu Q, Yasui Y, et al. Late mortality among 5-year survivors of childhood cancer: a summary from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2328–2338.

- Christen S, Weishaupt E, Vetsch J, et al. Perceived information provision and information needs in adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. Eur J Cancer Care. 2019;28:e12892.

- Kent EE, Arora NK, Rowland JH, et al. Health information needs and health-related quality of life in a diverse population of long-term cancer survivors. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;89:345–352.

- Murbraech K, Smeland KB, Holte H, et al. Heart failure and asymptomatic left ventricular systolic dysfunction in lymphoma survivors treated with autologous stem-cell transplantation: a national cross-sectional study. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:2683–2691.

- National manual with guidelines for the diagnosis, treatment and follow-up of malignant lymphomas, IS-nummer 2747 [Internet]. The Norwegian Health Directory [cited 2019 Jan 01]. Available from: https://www.helsedirektoratet.no/pakkeforlop/lymfomer

- Ware JE, Kosinski M, Gandek B. SF-36 health survey: manual & interpretation guide. 2nd ed. Boston (MA): Lincoln (RI): Health Assessment Lab; QualityMetric; 2000.

- Ware JE, Jr., Gandek B, Kosinski M, et al. The equivalence of SF-36 summary health scores estimated using standard and country-specific algorithms in 10 countries: results from the IQOLA Project. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51:1167–1170.

- Gandek B, Sinclair SJ, Kosinski M, et al. Psychometric evaluation of the SF-36 health survey in medicare managed care. Health Care Financ Rev. 2004;25:5–25.

- Chalder T, Berelowitz G, Pawlikowska T, et al. Development of a fatigue scale. J Psychosom Res. 1993;37:147–153.

- Loge JH, Ekeberg O, Kaasa S. Fatigue in the general Norwegian population: normative data and associations. J Psychosom Res. 1998;45:53–65.

- Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Haug TT, et al. The validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. An updated literature review. J Psychosom Res. 2002;52:69–77.

- Krokstad S, Langhammer A, Hveem K, et al. Cohort profile: the HUNT Study, Norway. Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42:968–977.

- World Health Organisation [Internet]. Global recommendation on physical activity for health; 2010. [cited 2019 Jun 21]. Available from: https://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/factsheet_adults/en/

- Shapiro CL. Cancer survivorship. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:2438–2450.

- Ross L, Petersen MA, Johnsen AT, et al. Satisfaction with information provided to Danish cancer patients: validation and survey results. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;93:239–247.

- Oktay K, Harvey BE, Loren AW. Fertility preservation in patients with cancer: ASCO clinical practice guideline update summary. J Oncol Pract. 2018;14:381–385.

- Dillon DG, Pizzagalli DA. Mechanisms of memory disruption in depression. Trends Neurosci. 2018;41:137–149.

- Husson O, Mols F, van de Poll-Franse LV. The relation between information provision and health-related quality of life, anxiety and depression among cancer survivors: a systematic review. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:761–772.

- Sutradhar R, Agha M, Pole JD, et al. Specialized survivor clinic attendance is associated with decreased rates of emergency department visits in adult survivors of childhood cancer. Cancer. 2015;121:4389–4397.

- Til deg som har fått strålebehandling for lymfekreft- viktig informasjon om forebygging om mulige senskader [To the patient who has received radiotherapy for lymphoma – important information on the prevention of late adverse effects]. The Norwegian Health Directory, The Norwegian Lymphoma Group, The Norwegian Cancer Association, editor. 2012. [cited 2019 Jun 21]. Available from: https://www.helsedirektoratet.no/brosjyrer/til-deg-som-har-fatt-stralebehandling-for-lymfekreft

- Bower JE, Bak K, Berger A, et al. Screening, assessment, and management of fatigue in adult survivors of cancer: an American Society of Clinical oncology clinical practice guideline adaptation. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:1840–1850.

- Campbell MK, Tessaro I, Gellin M, et al. Adult cancer survivorship care: experiences from the LIVESTRONG centers of excellence network. J Cancer Surviv. 2011;5:271–282.