Introduction

Increasing research has been conducted about patients’ preferences for their role in treatment decision making. Nowadays, a patient-centred approach, so-called ‘shared decision making,’ emphasises a more active role for patients and a more tailor-made approach by healthcare providers [Citation1–5].

Decision making shared between patients and healthcare providers could result in various benefits, including the improvement of patient satisfaction and clinical outcomes [Citation6–12]. Identifying patient preferences and improving patient-physician interactions for various types of cancer, especially breast cancer, have received considerable attention [Citation13–17]. To evaluate patients’ and physicians’ preferences, the Control Preferences Scale was used by Degner et al. for breast cancer patients [Citation18]. Similarly, regarding lung cancer, of which the morbidity and mortality rates are still high [Citation19,Citation20] surveying patients’ role in the treatment decision is increasingly important; however; studies have been limited until now [Citation21].

We investigated patients’ preferences for their role in decision making regarding lung cancer treatment and the relationship between the perceptions of patients and physicians regarding decision making. We also examined whether anxiety and depression status could affect patients’ perception of their roles in decision making.

Material and methods

Patients

Between January 2015 and August 2018, Japanese patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer in Okayama University Hospital who underwent cisplatin-containing chemotherapy and participated in a prospective randomised study (Okayama Lung Cancer Study Group 1406 Trial: OLCSG1406) comparing two forced diuretics for the prevention of nephrotoxicity were recruited [Citation22]. This study included the current study as a pre-planned subset analysis. Of the 44 recruited patients, 40 consented to this subset analysis; the remaining four failed to collect questionnaire forms. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Okayama University Hospital (approval no. m04009) and registered with the UMIN Clinical Trials Registry (UMIN000015293).

Study flow

The main outcome measures of this study were three parallel versions of a control preference scale (Supplementary Table S1) [Citation23]. All the participants were interviewed when recruited to the original randomised study but just before the initiation of cisplatin-based chemotherapy. Separate from this analysis, the original randomised study was comprehensively published elsewhere [Citation22].

Patients were interviewed using questionnaires that assessed sociodemographic background, psychosocial characteristics, and decision-making role outcomes. Patients were asked to indicate their preferences before providing informed consent for enrolment in the parent study and their perceptions after providing informed consent retrospectively. Sociodemographic characteristics included marital status, smoking status and education. Patients were also assessed using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) [Citation24] which measures anxiety and depression status in medically ill patients using a four-point 14-item self-assessment questionnaire. Physicians attending the patients were also interviewed and requested to answer questionnaires to assess their perceptions after obtaining the patient’s informed consent. This questionnaire was administered at a single time point and only assessed physicians’ perceptions of patients’ role during one consultation.

Data analysis

For these analyses, the patient preference scale was modified to three levels as reported previously (mostly patient, shared decision making, and mostly physician; Supplementary Table S1) [Citation25–27]. Fisher’s exact test was applied to evaluate differences among the groups. We used κ statistics and a test for symmetry to detect any agreement and discordance between patients’ preferences and perceptions and between patients’ and physicians’ perceptions. Moderate reproducibility was indicated by κ > 0.4 and good reproducibility by κ > 0.6; p < .05 in the symmetry test indicated significant concordance between two scales [Citation21,Citation28]. Statistical analyses were conducted using STATA version 14 software (College Station, TX, USA). Two-sided p-values <.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient characteristics

Patient characteristics are shown in Supplementary Table S2; among the 40 patients, most were married, female, and educated at high school level or below. Thirty (75%) and 10 (25%) of the 40 patients had been attended by the physician in charge for <1 month and 1–12 months before they were registered in this study, respectively. As for the clinical information, most had adenocarcinoma, and almost half had driver oncogenes such as epidermal growth factor receptor or anaplastic lymphoma kinase.

Regarding anxiety and depression status indicated by HADS-A and HADS-D scores, respectively, the median score was 6 for anxiety (range, 0–14) and 4 for depression (range, 0–11). A total of 12 physicians (10 men, two women) attended the 40 patients and informed them of their disease and possible treatment strategy. The physicians have 5–9 years of experience in clinical practice.

Decision preferences

Regarding patient preferences, nine (22%), 15 (38%), and 16 (40%) patients favoured an active, collaborative, and passive role in treatment decision making, respectively (Supplementary Table S3A). Although older patients tended to prefer a passive role, this preference pattern was not associated with any clinical or sociodemographic factors. In contrast, regarding patients’ perception of their own role in decision making, 16 (40%), 11 (28%), and 13 (32%) perceived an active, shared, and passive role, respectively. The pattern of perception of the decision-making role was also not correlated with any of the evaluated factors (Supplementary Table S3B).

Patient perceptions versus patient preferences and physician perceptions

(left) shows that 63% of the patients perceived that they played the role they had initially preferred, with moderate concordance between patient preferences and perceptions (κ = 0.45; symmetry test, p = .08). In contrast, (right) compares the perceptions of patients and physicians regarding the treatment decision, with an agreement rate of 35% (κ = 0.01; symmetry test, p = .26).

Table 1. Patient preferences and perceptions, and physician perceptions.

Association of HADS scores with the change in patients’ perception of their role in the treatment decision

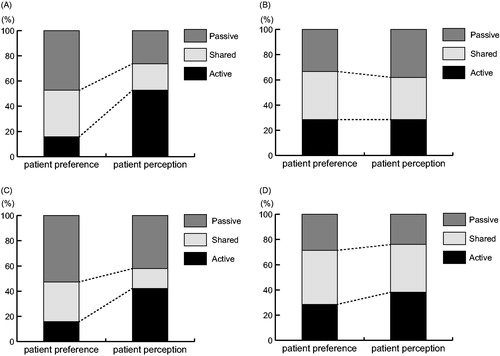

Next, we analysed the relationship between HADS-A/D score and patients’ preferences/perceptions. Overall, there was no significant change in patients’ preferences and perceptions before and after providing informed consent (). In contrast, when only those with low HADS-A/D scores were analysed, more patients perceived that they played an active role after providing informed consent for this study (A; 16% vs. 42%, D; 16% vs. 53%) (. Conversely, in high-HADS-A/D score patients, changes were insignificant (A; 29% vs. 38%, D; 29% vs. 29%) (.

Figure 1. Association between Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) scores and the change in patients’ preferences and perceptions of their role in the treatment decision. The 40 patients were divided into those with low (A) and high (B) depression scores with a cut-off value of 6, the median score. They were also subclassified as those with low (C) and high (D) anxiety scores with the median score of 4 as the cut-off value. (A) Low consistency between patient preferences and perceptions in 19 patients with low depression scores. The number of patients who perceived that they played an active role increased from three (16%) to 10 (53%) before and after providing informed consent, respectively. (B) High consistencyu in 21 patients with high depression scores, with six (29%) patients perceiving that they played an active role before and after providing informed consent. (C) Low consistency in 19 patients with low anxiety scores, with the number of patients perceiving that they played an active role increasing from three (16%) to eight (42%) before and after providing informed consent, respectively. (D) High consistency in 21 patients with high anxiety scores, with six (29%) and eight (38%) patients perceiving that they played an active role before and after providing informed consent, respectively.

Discussion

In this study, we revealed the following findings: (1) although patients who are younger, female, more educated, and have better health have been found to desire more active decisional roles in general, no clinical or sociodemographic factors affected patients’ preferences or perceptions of their own decision-making role, (2) although patients’ preferences and perceptions shows relatively high concordance, a critical discrepancy remained between the perceptions of patients and physicians, and (3) despite no specific trend in the entire cohort, more patients with lower HADS-A/D scores tended to perceive that they played an active role after providing informed consent than patients with higher HADS-A/D scores (.

A relatively high concordance between patient preferences and perceptions means that patients’ decision-making roles did not change substantially before and after providing informed consent. In recent decades, paternalism, which deprecated patient-centred decision making in the clinical setting, has gradually disappeared [Citation2,Citation29]. This may explain why the concordance between patients’ preferences and perceptions was retained. Nevertheless, this result is worthy of evaluation since a similar result was also demonstrated in other reports, including our prior study [Citation21]. In contrast, the concordance rate for patient and physician perceptions was only 35%, indicating that physicians did not adequately perceive their patients’ view of their decision-making role. Notably, the concordance rate was lower than that in our previous study (54%) [Citation21]. This would partly be attributable to the relatively short patient-attended period in this study; 75% vs. 30% of patients had been followed by the physician for only 1 month in the present vs. previous studies. Recently, communication skills training was reported to improve physicians’ ability to understand patients’ preferences for their own decision-making role [Citation30]. Physicians still need to devote themselves to further continuous self-improvement.

Notably, more patients with low anxiety/depression scores perceived that they played an active role after providing informed consent (. These patients might have had the ability to participate in a more active manner according to the situation. Indeed, such patients have better information processing abilities [Citation31,Citation32]. In contrast, no specific changes and trends were observed in patients with high anxiety/depression scores (). To obtain informed consent as spontaneously as possible, a pre-screening of patients’ anxiety/depression status would be helpful for physicians; developing a novel communication style especially for those with anxiety or depression may be necessary. HADS screening is simple and convenient; thus, further verification of its usefulness is warranted. In this study, we used the median of the HADS scores for convenience to identify concordance between anxiety or depression status and patients’ preferences or perceptions. Therefore, this result should be interpreted with caution.

Our study had several limitations. First, the limited number of patients could have resulted in data with insufficient power to detect significance between patients’ preferences and perceptions. Second, since the 40 patients were attended by as many as 12 doctors, we could not be sure of the homogeneity of information provided to the patients about disease status and suitable treatment options. Third, although the treatment protocols for enrolled patients were essentially homogeneous, patients did not receive exactly the same treatment combinations or schedules; therefore, information provided to patients may have differed and thus influenced their perceptions to some extent. Furthermore, this was a single-centre study which could have led to selection bias. Thus, our results should be interpreted with caution and confirmed using large-scale multicentre data to clarify the generalizability.

In conclusion, despite no significant changes in the entire cohort, patients with low HADS-A/D scores tended to perceive that they played an active role in decision making after providing informed consent. The discordance between patients’ and physicians’ perceptions remains a major problem. We must endeavour to narrow this gap, for example through communication skills training focussing on patients’ preferences.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (43.8 KB)Acknowledgments

This study was conducted with support from the Centre for Innovative Clinical Medicine, Okayama University Hospital. We thank the following investigators and all other investigators at Okayama University Hospital: Drs. Yosuke Toyota, Satoru Senoo, Takahiro Umeno, Naohiro Oda, Hisao Higo, Chihiro Ando, Atsuko Hirabae, Yoshitaka Iwamoto, and Kammei Rai. We also thank Drs. Mikio Kataoka and Masafumi Fujii as members of the Data and Safety Monitoring Board. We are also thankful to Hiromi Matsushita and Kaori Ohashi for supporting this study.

Disclosure statement

K.H. reports grants and personal fees from AZ, grants and personal fees from Lilly, grants and personal fees from BMS, personal fees from MSD, personal fees from Ono, personal fees from NipponKayaku, personal fees from Taiho, personal fees from BI, and personal fees from Chugai outside the submitted work. K. K. has received honoraria from Eli Lilly Japan, Nihon Kayaku, AstraZeneca, Daiichi-Sankyo Pharmaceutical, Chugai Pharmaceutical, Taiho Pharmaceutical, and Sanofi-Aventis. The remaining authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- Moloney TW, Paul B. The consumer movement takes hold in medical care. Health Aff (Millwood). 1991;10(4):268–279.

- Laine C, Davidoff F. Patient-centered medicine. A professional evolution. JAMA. 1996;275(2):152–156.

- Deber RB, Kraetschmer N, Irvine J. What role do patients wish to play in treatment decision making? Arch Intern Med. 1996;156(13):1414–1420.

- Slatore CG, Sullivan DR, Pappas M, et al. Patient-centered outcomes among lung cancer screening recipients with computed tomography: a systematic review. J Thorac Oncol. 2014;9(7):927–934.

- Gorman JR, Standridge D, Lyons KS, et al. Patient-centered communication between adolescent and young adult cancer survivors and their healthcare providers: identifying research gaps with a scoping review. Patient Educ Couns. 2018;101(2):185–194.

- Greenfield S, Kaplan S, Ware JE Jr. Expanding patient involvement in care. Effects on patient outcomes. Ann Intern Med. 1985;102(4):520–528.

- Greenfield S, Kaplan SH, Ware JE Jr, et al. Patients' participation in medical care: effects on blood sugar control and quality of life. J Gen Intern Med. 1988;3(5):448–457.

- Kaplan SH, Greenfield S, Ware JE Jr. Assessing the effects of physician-patient interactions on the outcomes of chronic disease. Med Care. 1989;27(Supplement):S110–S127.

- Brody DS, Miller SM, Lerman CE, et al. Patient perception of involvement in medical care: relationship to illness attitudes and outcomes. J Gen Intern Med. 1989;4(6):506–511.

- Ashcroft JJ, Leinster SJ, Slade PD. Breast cancer-patient choice of treatment: preliminary communication. J R Soc Med. 1985;78(1):43–46.

- Morris J, Ingham R. Choice of surgery for early breast cancer: psychosocial considerations. Soc Sci Med. 1988;27(11):1257–1262.

- Deadman JM, Leinster SJ, Owens RG, et al. Taking responsibility for cancer treatment. Soc Sci Med. 2001;53(5):669–677.

- Janz NK, Wren PA, Copeland LA, et al. Patient-physician concordance: preferences, perceptions, and factors influencing the breast cancer surgical decision. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(15):3091–3098.

- Vogel BA, Helmes AW, Hasenburg A. Concordance between patients' desired and actual decision-making roles in breast cancer care. Psychooncology. 2008;17(2):182–189.

- Broughman JR, Basak R, Nielsen ME, et al. Prostate cancer patient characteristics associated with a strong preference to preserve sexual function and receipt of active surveillance. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2018;110(4):420–425.

- Huibertse LJ, van Eenbergen M, de Rooij BH, et al. Cancer survivors' preference for follow-up care providers: a cross-sectional study from the population-based PROFILES-registry. Acta Oncol. 2017;56(2):278–287.

- Fu AZ, Graves KD, Jensen RE, et al. Patient preference and decision-making for initiating metastatic colorectal cancer medical treatment. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2016;142(3):699–706.

- Degner LF, Kristjanson LJ, Bowman D, et al. Information needs and decisional preferences in women with breast cancer. JAMA. 1997;277(18):1485–1492.

- Tanaka H. Advances in cancer epidemiology in Japan. Int J Cancer. 2014;134(4):747–754.

- Hori M, Matsuda T, Shibata A, et al. Cancer incidence and incidence rates in Japan in 2009: a study of 32 population-based cancer registries for the Monitoring of Cancer Incidence in Japan (MCIJ) project. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2015;45(9):884–891.

- Hotta K, Kiura K, Takigawa N, et al. Desire for information and involvement in treatment decisions: lung cancer patients' preferences and their physicians' perceptions: results from Okayama Lung Cancer Study Group Trial 0705. J Thorac Oncol. 2010;5(10):1668–1672.

- Makimoto G, Ichihara E, Hotta K, et al. Randomized phase ii study comparing mannitol with furosemide for the prevention of renal toxicity induced by cisplatin-based chemotherapy with short-term low-volume hydration in advanced non-small cell lung cancer: The OLCSG1406 Study Protocol. Acta Med Okayama. 2018;72(3):319–323.

- Degner LF, Sloan JA. Decision making during serious illness: what role do patients really want to play? J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45(9):941–950.

- Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67(6):361–370.

- Elkin EB, Kim SH, Casper ES, et al. Desire for information and involvement in treatment decisions: elderly cancer patients' preferences and their physicians' perceptions. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(33):5275–5280.

- Jansen SJ, Otten W, Stiggelbout AM. Factors affecting patients' perceptions of choice regarding adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006;99(1):35–45.

- Mallinger JB, Shields CG, Griggs JJ, et al. Stability of decisional role preference over the course of cancer therapy. Psychooncology. 2006;15(4):297–305.

- Kundel HL, Polansky M. Measurement of observer agreement. Radiology. 2003;228(2):303–308.

- Chewning B, Bylund CL, Shah B, et al. Patient preferences for shared decisions: a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;86(1):9–18.

- Fujimori M, Shirai Y, Asai M, et al. Effect of communication skills training program for oncologists based on patient preferences for communication when receiving bad news: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(20):2166–2172.

- Labiano-Fontcuberta A, Mitchell AJ, Moreno-Garcia S, et al. Anxiety and depressive symptoms in caregivers of multiple sclerosis patients: the role of information processing speed impairment. J Neurol Sci. 2015;349(1-2):220–225.

- Brand N, Jolles J. Information processing in depression and anxiety. Psychol Med. 1987;17(1):145–153.