Introduction

In 2012, it was estimated that 430,000 cases of bladder cancer (BC) occurred worldwide [Citation1] with high incidence and mortality in Europe. BC remains a heavy burden for patients and costly for the society in general, especially because of the tendency for recurrence. BC has thus become a major public health concern, a great challenge for health economics with a particularly important impact in the elderly population since the median age at diagnosis lies early in the eighth decade [Citation2]. Moreover, BC-specific mortality is higher in older people [Citation3,Citation4]. Consequently, many questions rose concerning appropriate management practices in this population especially regarding aggressive protocols proposed for the treatment of BC [Citation5].

The aim of the study was to assess, in a general population setting, the impact of age on management practices for BC cases with the highest risk of recurrence or local or distant progression. The risk-benefit balance of current treatments in terms of prognosis among the oldest subjects will be discussed.

Material and methods

Population

BCs were identified from a population-based general cancer registry located in Northern France (800,000 inhabitants). In this geographic area, healthcare services are provided by general, public, private, teaching hospitals, radiotherapy centers and a cancer care center. The registry meets the eligibility criteria to be included in the CI5 monograph series [Citation6].

Tumors are coded according to international guidelines [Citation7]. Incident bladder tumors from benign to at least T1 [Citation8] are recorded. BCs incident in 2011 and 2012 were considered, except for ourachal tumors. Non-muscle-invasive bladder cancers were classified according to potential risk for progression or/and recurrence following criteria adapted from the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer risk tables [Citation9,Citation10]. High-risk NMIBCs (HR-NMIBCs) and at least (pathological/clinical) T2 BCs- muscle-invasive BCs (MIBCs)- were studied.

Data collection

Clinical parameters were retrieved from medical files.

Information on management practices within one year of diagnosis was collected. Assessment during a multidisciplinary team (MDT) meeting in urologic oncology is a mandatory step in oncologic practice in France. Date of first assessment and decision made were collected. Cystectomy, intravesical instillation, concomitant chemo-radiotherapy, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy were considered as specific treatments. Time to assessment, and time to specific treatment, was the time elapsed between the date of diagnosis (diagnostic transurethral resection of the bladder (TURB) or surgical sampling or clinical diagnosis for cases without pathological analysis) and the date of the first MDT assessment, and the date of first treatment, respectively.

Age was considered as a qualitative variable (≤64, 65–74, ≥75 years old). HR-NMIBCs were classified according to the pathological stage of the tumor at the end of the diagnostic step. MIBCs were classified according to their extent at diagnostic imaging as: N0M0, N + M0, M+, or NxMx [Citation8]. The Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) was calculated from relevant comorbidities [Citation11].

Follow-up was retrieved through December 31th, 2015. Specific mortality referring to deaths due to urinary cancer or related to its treatment was coded according to information available in medical files.

Statistical analyses

All analyses were performed separately for HR-NMIBCs and MIBCs.

Among cases assessed in MDT, we compared time to assessment between age groups using the Kruskall-Wallis test.

We assessed the association between receiving a specific treatment and age by using Fine and Gray models with treatment delivery as the event of interest and death as a competing event since death could have precluded treatment, especially for the oldest patients. For HR-NMIBC, progression to invasive tumor was also a competing event. The association was adjusted for disease stage (restricted to non-metastatic vs metastatic for MIBC) and CCI. Subjects who were not treated and alive –and who did not progress to MIBC for HR-NMIBC- at one year of follow-up were censored. We derived from Fine and Gray models sub Hazard Ratio as effect size [Citation12].

Among subjects who received the commonest specific treatment, we compared the time to treatment between age groups using a Kruskall-Wallis test.

Finally, we assessed BC-specific mortality among subjects aged at least 65 years at diagnosis using competing risk analysis, with other cause of death as a competing event. We performed a multivariable Fine and Gray model including age groups, CCI, stage at diagnosis, and treatment analyzed as a time-depending variable. Patients alive on December 31th, 2015 were censored.

Statistical testing was done at the two-tailed α level of 0.05. Data were analyzed using the SAS software package, release 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Population is described in Supplementary Table 1. Out of 538 incident BCs in 2011–2012, 98 (18.2%) were HR-NMIBCs and 147 (27.3%) were MIBCs. The median age at diagnosis of HR-NMIBC and MIBC was 74.0 and 73.6 years respectively. One out of ten subjects with HR-NMIBC and one out of five with MIBC was a woman. The CCI score of subjects aged at least 65 at diagnosis of HR-NMIBC was higher than that of younger subjects.

HR-NMIBC

Among 98 HR-NMIBCs, 72 were assessed in MDT meetings (). Rate of cases assessed appeared quiet similar across age groups. Among cases assessed, time to assessment did not differ according to age group (p = .3).

Table 1. Time to Multidisciplinary team (MDT) meeting in oncologic urology assessment and time to the commonest treatment according to age, for high risk non-muscle invasive bladder cancer and muscle invasive bladder cancer.

Six subjects were lost to follow-up before management and were not included in the analyses dealing with treatment and mortality. Among the other 92, only age was related to receiving a specific treatment. With reference to subjects younger than 65, those aged at least 75 were less likely to receive specific treatment (sub hazard ratio (SHR) 0.25 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.14–0.45). Further dividing the oldest age group by two (75–80 and at least 81 years old) lead to obtain this same SHR in these two groups ().

Table 2. Adjusted sub hazard ratio (SHR) for receiving a specific treatment, results of the competing risk models.

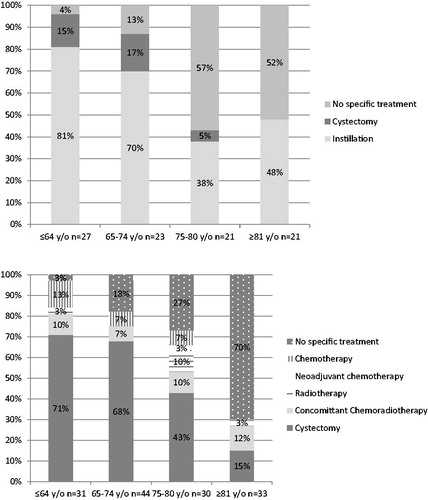

details type of treatment delivered according to age. The commonest treatment was intravesical instillations. Time to first instillation differed significantly according to age: it was the longest for the oldest age group but shorter for those aged 65–74 ().

During the follow-up, 17 of the 65 subjects aged at least 65 at diagnosis of HR-NMIBC died from BC. BC-specific mortality rate was 26.6% (95% CI 15.7–37.4). Specific mortality was only significantly related to comorbidities that increased the risk of death (SHR 1.56 95% CI 1.01–2.42).

MIBC

Almost all MIBCs were assessed in MDT meetings (). Among cases assessed, time to assessment did not differ according to age group (p = .5).

Nine subjects were lost to follow-up before management and were not included in the following analyses. For the other 138, with reference to subjects younger than 65, once more, those aged at least 75 were less likely to receive MIBC treatment (SHR 0.33 95% CI 0.17–0.62). By dividing the oldest group by two, SHR was 0.48 95% CI 0.25–0.92 for people aged 75–80 and 0.16 95% CI 0.06–0.42 for those aged at least 81.

details type of treatment according to age. The commonest treatment was surgery. Median time to surgery first did not differ according to age group (p = .4) ().

During the follow-up, 67 of the 107 subjects aged at least 65 at diagnosis of MIBC died from BC: BC-specific mortality rate was 62.6% (95% CI 53.5–71.8). In analyses restricted to those whose stage at diagnosis was known, specific mortality was significantly related to receiving a treatment (SHR: 0.44 95% CI 0.21–0.95), which had a positive effect on survival, despite the deleterious effect of the disease stage (SHR: 5.62 95% CI 2.60–12.05).

Discussion

This general population-based study provided the opportunity to analyze recent care practices for patients with a follow-up long enough to assess mortality. It pointed out the longstanding issue of appropriate management practices for elderly patients with BC. In 2011–2012, in northern France, few elderly people received specific guidelines-recommended treatment. Age seemed to influence management practices. Nonetheless, among the older subjects with MIBC, specific mortality appeared lower for those who received specific treatment.

MDT outcomes appeared unrelated to age. Nonetheless, improving assessment rate for HR-NMIBCs may lead to enhance their treatment.

Few people aged at least 75 were treated, whether for HR-NMIBC or for MIBC. Differences in study populations, tumor and evolving practices hinder comparisons between series. Nonetheless, older series from the 1990–2000s reported a lack of BCG treatment for the oldest subjects [Citation13–15]; only in the Netherlands, 90% of high grade T1 subjects received BCG-therapy [Citation16]. The present report does not support this management to improve. In 2011, in France, the life expectancy of a 75-year-old subject was 13 years [Citation17]. This raises the relevance of achieving a specific treatment for septuagenarians, knowing the adverse evolving potential of HR-NMIBC. Although observations concerning the tolerance of BCG instillations in older people have been discordant, there is no evidence of lower tolerance among them sufficient to explain its underuse [Citation18]. With a well-conducted BCG, risks of recurrence and heavier curative treatment in elderly can be reduced. It remains that for some authors, aging appears to be associated with worse outcomes encouraging BCG underutilization particularly for the oldest old (>80) [Citation19,Citation20]. However, BCG remains the reference treatment [Citation21,Citation22]. In addition, a prompter treatment might be beneficial for some patients as the time to onset of instillations appeared long for the oldest. A shortage of BCG that occurred in Europe (since May 2012 in France) may affect therapeutic practices.

In many studies, rate and types of treatment delivered for MIBC varied with age [Citation14,Citation23], even recently [Citation24,Citation25]. Only one study reported between 2004 and 2013 more than 40% of the octo-/nonagenarians with local carcinoma receiving specific treatment [Citation26]. Cystectomy is a complex surgical procedure associated with high risk of complications [Citation27] and for older adults, 90-day mortality rates as high as 15% were reported [Citation28]. Concomitant chemoradiotherapy was sometimes suggested as an alternative treatment for older people [Citation29]. Finally, a positive outcome was time to cystectomy which was in agreement with the guidelines for almost all, including the elderly [Citation10].

Oncogeriatric management must meet several challenges to ensure the recommended specific therapeutic choices [Citation30,Citation31]. Medical, social, functional, sensorial aspects must be considered . Also, screening tools help to identify subjects who may benefit from an oncogeriatric evaluation before treatment [Citation32]. Assessing the risk/benefit balance of treating BC in elderly is a major issue. It is all the more important considering the growing aging population in many countries. Furthermore, BC practice guidelines do not consider age as a limiting factor.

Finally, BC-related mortality among elderly subjects with HR-NMIBC or MIBC appeared to be high. The Registry area is known to have high BC incidence and mortality [Citation33]. Indeed, the region’s industrial past and the inhabitants’ lifestyle led to a concentration of BC risk factors. Specific mortality for those with HR-NMIBC did not appear to be associated with treatment unlike in the SEER-Medicare [Citation34,Citation35], but the sample was small. By contrast, among those with MIBC, even if it can not be ruled out that those who received a treatment were fitter than those who did not, specific mortality adjusted for comorbidities and stage was lower for those who received a treatment even considering non-curative treatments.

This study provides a rare source of information concerning current management practices for BC with no selection for participant or treatment. Relevant data, including comorbid conditions, were retrieved from medical files. The major weakness was the number of subjects, which limited the scope of the analyses, especially sex-specific analyses. Also, other issues such as performance status that may be important in the relationship studied were not addressed. In addition, since no detailed oncogeriatric assessment was available, whether or not abstaining from treating was the best therapeutic option could not be determined.

Conclusion

Recently, in northern France, age seemed to limit the delivery of specific treatments for the most serious cases of BC as recommended by practice guidelines. Nonetheless, among the oldest suffering from MIBC, receiving a treatment appeared to reduce BC-specific mortality. This finding highlights that, beyond chronological age, a comprehensive oncogeriatric assessment at diagnosis is important to implement specific management practices that would better match care guidelines. For patients with BC, further study of detailed oncogeriatric assessments is needed to discriminate well-adapted care practices from insufficient treatment.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (44.6 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors thanks the staff of the Onco-Nord-Pas-de-Calais network staff.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- Antoni S, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, et al. Bladder cancer incidence and mortality: a global overview and recent trends. Eur Urol. 2017;71(1):96–108.

- Cancer Stat Facts: Bladder Cancer [Internet]. [cited 2018 Oct 20]. Available from: https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/urinb.html.

- Fonteyne V, Ost P, Bellmunt J, et al. Curative treatment for muscle invasive bladder cancer in elderly patients: a systematic review. Eur Urol. 2018;73(1):40–50.

- Cowppli-Bony A, Uhry Z, Remontet L, et al. Survival of cancer patients in metropolitan France, 1989–2013. Part 1-Solid tumors. Saint-Maurice (France): Institut de veille sanitaire; 2016.

- Jensen TK, Jensen NV, Jørgensen SM, et al. Trends in cancer of the urinary bladder and urinary tract in elderly in Denmark, 2008–2012. Acta Oncol Stockh Swed. 2016;55(sup1):85–90.

- CI5 XI - Home [Internet]. [cited 2019 Oct 15]. Available from: http://ci5.iarc.fr/CI5-XI/Default.aspx.

- Tyczynski JE, Demaret E, Parkin DM. Standards and Guidelines for Cancer Registration in Europe [Internet]. [cited 2020 Jan 17]. Available from: https://publications.iarc.fr/Book-And-Report-Series/Iarc-Technical-Publications/Standards-And-Guidelines-For-Cancer-Registration-In-Europe-2003.

- Sobin L, Gospodarowicz MK, Wittekind C. TNM classification of malignant tumours. 7th ed. LH Sobin, MK Gospodarowicz and Ch. Wittekind, editor; New York: Wiley-Liss, Inc; 2009.

- Sylvester RJ, van der Meijden APM, Oosterlinck W, et al. Predicting recurrence and progression in individual patients with stage Ta T1 bladder cancer using EORTC risk tables: a combined analysis of 2596 patients from seven EORTC trials. Eur Urol. 2006;49(3):466–465.

- Pfister C, Roupret M, Wallerand H, et al. [Recommendations onco-urology 2010: urothelial tumors]. Progres En Urol. 2010;20(Suppl 4):S255–S274.

- Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–383.

- Austin PC, Fine JP. Practical recommendations for reporting Fine-Gray model analyses for competing risk data. Stat Med. 2017;36(27):4391–4400.

- Chamie K, Saigal CS, Lai J, et al. Compliance with guidelines for patients with bladder cancer: variation in the delivery of care. Cancer. 2011;117(23):5392–5401.

- Noon AP, Albertsen PC, Thomas F, et al. Competing mortality in patients diagnosed with bladder cancer: evidence of undertreatment in the elderly and female patients. Br J Cancer. 2013;108(7):1534–1540.

- Patschan O, Holmäng S, Hosseini A, et al. Use of bacillus Calmette-Guérin in stage T1 bladder cancer: long-term observation of a population-based cohort. Scand J Urol. 2015;49(2):127–132.

- Goossens-Laan CA, Visser O, Wouters M, et al. Variations in treatment policies and outcome for bladder cancer in the Netherlands. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2010;36(Suppl 1):S100–S107.

- Table de Mortalité Des Années 2009–2011 [Internet]. [cited 2018 Oct 29]. Available from: https://www.insee.fr.

- Oddens J R, Sylvester R J, Brausi M A, et al. Increasing age is not associated with toxicity leading to discontinuation of treatment in patients with urothelial non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer randomised to receive 3 years of maintenance bacille Calmette-Guérin: results from European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Genito-Urinary Group study 30911. BJU Int. 2016;118(3):423–428.

- Joudi FN, Smith BJ, O’Donnell MA, et al. The impact of age on the response of patients with superficial bladder cancer to intravesical immunotherapy. J Urol. 2006;175(5):1634–1639.

- Herr HW. Age and outcome of superficial bladder cancer treated with bacille Calmette-Guérin therapy. Urology. 2007;70(1):65–68.

- Babjuk M, Burger M, Zigeuner R, et al. EAU guidelines on non–muscle-invasive urothelial carcinoma of the bladder: update 2013. Eur Urol. 2013;64(4):639–653.

- Roupret M, Neuzillet Y, Masson-Lecomte A, et al. Recommandations en onco-urologie 2016–2018 du CCAFU: tumeurs de la vessie. Prog Urol. 2016;27:S67–S91.

- Goossens-Laan CA, Leliveld AM, Verhoeven RHA, et al. Effects of age and comorbidity on treatment and survival of patients with muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Int J Cancer. 2014;135(4):905–912.

- Gray PJ, Fedewa SA, Shipley WU, et al. Use of potentially curative therapies for muscle-invasive bladder cancer in the United States: results from the National Cancer Data Base. Eur Urol. 2013;63(5):823–829.

- Williams SB, Huo J, Chamie K, et al. Underutilization of radical cystectomy among patients diagnosed with clinical stage T2 muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Eur Urol Focus. 2017;3:258–264.

- Fischer-Valuck BW, Rao YJ, Rudra S, et al. Treatment patterns and overall survival outcomes of octogenarians with muscle invasive cancer of the bladder: an analysis of the National Cancer Database. J Urol. 2018;199(2):416–423.

- Novara G, De Marco V, Aragona M, et al. Complications and mortality after radical cystectomy for bladder transitional cell cancer. J Urol. 2009;182(3):914–921.

- Schiffmann J, Gandaglia G, Larcher A, et al. Contemporary 90-day mortality rates after radical cystectomy in the elderly. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2014;40:1738–1745.

- Boustani J, Bertaut A, Galsky MD, et al. Radical cystectomy or bladder preservation with radiochemotherapy in elderly patients with muscle-invasive bladder cancer: retrospective International Study of Cancers of the Urothelial Tract (RISC) Investigators. Acta Oncol Stockh Swed. 2018;57(4):491–497.

- Robinson TN, Eiseman B, Wallace JI, et al. Redefining geriatric preoperative assessment using frailty, disability and co-morbidity. Trans Meeting Am Surg Assoc. 2009;127:93–99.

- Mohile SG, Dale W, Somerfield MR, et al. Practical assessment and management of vulnerabilities in older patients receiving chemotherapy: ASCO guideline for geriatric oncology. J Oncol Pract. 2018;36(22):2326–2347

- Soubeyran P, Bellera C, Goyard J, et al. Screening for vulnerability in older cancer patients: the ONCODAGE prospective multicenter cohort study. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(12):e115060.

- Lapôtre-Ledoux B, Plouvier S, Cariou M, et al. Regional estimatie of incidence and mortality from cancers in France, 2007–2016. Hauts-de-France. Saint-Maurice: Santé publique France; 2019.

- Spencer BA, McBride RB, Hershman DL, et al. Adjuvant intravesical bacillus calmette-guérin therapy and survival among elderly patients with non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer. J Oncol Pract. 2013;9(2):92–98.

- Chamie K, Saigal CS, Lai J, et al. Quality of care in patients with bladder cancer: a case report? Cancer. 2012;118(5):1412–1421.