Background

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) remains a leading cause of cancer death worldwide [Citation1]. While current first line therapy for unresectable HCC consists of molecularly targeted agents including sorafenib and lenvatinib, these options are often poorly tolerated and offer limited chances of sustained remission [Citation2–5]. Nivolumab, an anti-programmed death receptor-1 (PD-1) monoclonal antibody, was recently demonstrated to be an effective second line alternative in unresectable HCC by the CheckMate 040 trial [Citation6]. However, this trial found nivolumab to be associated with an objective response rate (ORR) of only approximately 19%, with the majority of patients progressing despite treatment.

Radiation therapy (RT) has been shown to enhance the response to immune checkpoint inhibitors in the preclinical setting [Citation7–9]. While the mechanistic determinants remain uncertain, RT is known to induce immunogenic cell death wherein release of tumor neoantigens prime cytotoxic T lymphocytes against the irradiated tumor [Citation10,Citation11]. Clinically, this synergy has been linked to improved ORR and overall survival among previously irradiated patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors in other cancers [Citation12,Citation13].

Given this potential synergy, RT is an attractive option for combination therapy with nivolumab in the upfront or salvage treatment of HCC, both as a means to provide local control and to enhance global anti-tumor immune response. Additionally, combination treatment with RT and nivolumab in HCC appears safe and generally well tolerated [Citation14]. However, the effect of either upfront or salvage RT on ORR and outcomes in HCC patients treated with nivolumab remains largely unknown. We sought to quantify the ORR to combined radioimmunotherapy with nivolumab and either upfront or salvage RT among patients with unresectable or metastatic HCC.

Methods

Study Design

We reviewed patients who underwent RT for HCC at our institution between 1 January 2012 and 30 September 2018 who were subsequently or concurrently treated with nivolumab. Any treatment with external beam RT for HCC was sufficient for inclusion. Patients were excluded who had mixed histology cancers, other active malignancies, or who received prior radioembolization with Y-90. The primary endpoint was ORR based on modified response evaluation criteria in solid tumors (mRECIST) [Citation15]. Secondary endpoints included progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS). This study was approved by our institutional review board.

Patients were divided into upfront and salvage cohorts based on the timing of RT delivery. Upfront RT was defined as occurring prior to or overlapping with the first cycle of nivolumab; initiation of nivolumab served as the baseline for mRECIST and survival outcomes. Salvage RT was defined as RT to sites of persistent or progressive disease at least 4 weeks after start of nivolumab; in this cohort start of salvage RT served as the baseline for mRECIST and survival outcomes.

Data collection

Patient demographic, medical, and treatment-specific data were abstracted from our institutional electronic medical record (EMR). ORR was determined using mRECIST based on review of relevant imaging using Mint software (Heidelberg, Germany). All imaging review was performed by two independent radiologists. Patients for whom no post-baseline imaging was available were included and scored as not evaluable (NE). Patients achieving a complete response (CR) or partial response (PR) according to mRECIST were defined as having an objective response (OR); patients with stable disease (SD), progressive disease (PD), or who were NE were considered non-responders. While not included in primary mRECIST determination, response in irradiated versus non-irradiated lesions was noted and additional analysis was undertaken to determine the ORR specifically excluding previously irradiated lesions. Responses occurring after a change in systemic therapy or additional locoregional therapy were not considered. PFS and OS outcomes were measured from baseline with censoring at change of systemic therapy, delivery of additional locoregional therapy, or loss to follow-up for PFS and at loss to follow-up alone for OS.

Statistical analysis

ORRs for the upfront and salvage cohorts were calculated with associated 95% confidence intervals (CI) estimated using the Wilson score interval method. Survival outcomes were determined using Kaplan-Meier estimates and compared for responders versus non-responders using the log-rank test. Given the limited number of patients in our salvage RT cohort and inherent differences between these groups, no survival comparisons for upfront versus salvage RT were undertaken.

Results

We identified 35 patients who met inclusion criteria, including 26 in the upfront and 9 in the salvage cohorts. Median follow-up was 12.9 months. Among patients in the upfront cohort, 8 (31%) received RT during the first cycle of nivolumab and 18 (69%) completed RT a median of 3.8 months (range: 4 days–57 months) prior to nivolumab. Most patients were male (83%), had Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer stage C disease (91%), or had viral hepatitis etiology (86%). Twenty-five (71%) patients had metastatic disease and 16 (46%) had evidence of vascular invasion. RT was delivered to a median dose of 4,000 cGy (range: 800–6,000 cGy) and to the liver in 24 cases (67%). Stereotactic body radiation therapy technique was utilized in 17 cases (47%).

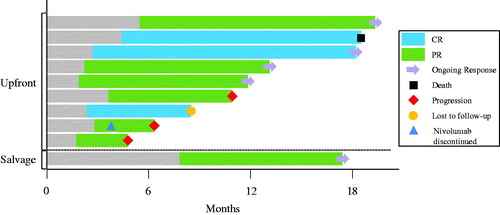

Among those who received upfront RT, the ORR was 34.6% (n = 9) (95% CI 19.4–53.8%) including 3 patients (11.5%) with CR and 6 patients (23.1%) with PR. The remaining patients in the upfront cohort had a best mRECIST score of SD (n = 2, 7.7%), PD (n = 10, 38.5%), or NE based on lack of follow-up imaging (n = 5, 19.2%). These results are detailed in . Among patients in the upfront RT cohort, there was no difference in ORR among those who received RT prior to versus concurrent with the first cycle of nivolumab (33% vs. 38%, respectively) (Fischer exact p = 1.00). Of 9 patients who achieved an OR, 6 demonstrated responses both within and outside the irradiated lesions while the remaining 3 demonstrated responses in the irradiated lesions with no evaluable disease elsewhere. In no case was an observed objective response isolated to an RT treated lesion with unresponsive or progressive disease elsewhere. Secondary analysis excluding irradiated lesions yielded an ORR of 30.4% (n = 7) (95% CI 15.6–50.9%) with 2 patients (8.7%) achieving CR and 5 patients (21.7%) achieving PR across 23 evaluable patients.

Table 1. Response to combination nivolumab and RT by mRECIST criteria.

In the salvage RT cohort, the ORR was 11.1% (n = 1) (95% CI 2.0–43.5%) consisting of a single patient who achieved a PR in an irradiated lesion alone with stable disease elsewhere. The remaining patients in the salvage cohort had SD (n = 1, 11.1%), PD (n = 4, 44.4%), or were NE due to lack of follow-up imaging (n = 3, 33.3).

After a median follow-up of 17.8 months among responders, the median duration of response was 9.8 months including 5 patients (50%) with continued response at last follow-up. The remaining responders developed progression of disease (n = 3, 30%), were lost to follow-up (n = 1, 10%), or died without progression of disease (n = 1, 10%). These data are illustrated in . The median PFS for responders was not reached compared to 2.3 months for non-responders (p < .001). The median OS for responders was not reached compared to 22.7 months for non-responders (p = .068).

Discussion

In our study, upfront RT and nivolumab was associated with an increased ORR compared to historical controls of nivolumab alone [Citation6,Citation16]. Whereas the CheckMate 040 trial reported a 19.1% ORR among all patients (combined expansion- and dose-escalation phases), we found the ORR to radioimmunotherapy to be 34.6% (95% CI 19.4–53.8%) in the upfront RT cohort [Citation6]. While some component of this increased ORR may be attributable to the direct effects of RT on targeted lesions, responses were observed both within and outside of the irradiated volume. Moreover, responses proved durable, with a median duration of response of 10.0 months in the upfront RT setting. While direct comparisons with prior studies should be undertaken with caution, these data are suggestive of potential synergy between nivolumab and RT in the upfront setting.

Conversely, salvage RT to sites of residual or progressive disease during nivolumab treatment failed to stimulate an OR outside of the RT field in our cohort. The reasons for the observed difference from the upfront RT setting are not immediately clear. However this may corroborate studies in other disease sites that suggest RT during maintenance immune checkpoint inhibition is less effective than RT prior to immune checkpoint inhibition [Citation17]. Multiple other factors could alternatively account for this difference including potential biological differences between cancers that progress on nivolumab and those that are immune checkpoint inhibition naive. Given our limited number of patients receiving salvage RT, it is additionally possible that a synergistic effect may yet exist that would only become apparent with many more observations.

PFS was significantly improved in patients who demonstrated an OR with a strong trend toward improved OS, further validating the role of tumor response based on mRECIST as a predictor of outcomes in advanced HCC [Citation18]. While not surprising, this finding is non-trivial and suggests that efforts to improve the ORR may immediately translate to improvement in ‘harder’ oncologic endpoints. As such efforts to increase the ORR among patients receiving immune checkpoint inhibition for HCC must be undertaken. While dual PD-1/cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) blockade has demonstrated improved ORR in other cancers, and has therefore attracted interest in HCC, this combination is also associated with substantially increased toxicity [Citation19–22]. Our findings are in line with previous clinical and preclinical work, which suggest exposure to RT may enhance the effectiveness of immunotherapy in solid malignancies without heightened toxicity [Citation7,Citation12,Citation17,Citation23].

Our study has several limitations, the foremost being its retrospective design. To mitigate the potential biases associated with this study design, we were careful to include all patients who met inclusion criteria during our study period and chose to define our primary outcome based on a well-validated, highly rigorous standard. The choice of mRECIST to score objective response was due to its high inter- and intra-observer reproducibility and its applicability to clinical practice in HCC [Citation18,Citation24]. A second important limitation of our study is the heterogeneity of our study population, which included patients who received RT at widely differing times in their disease process. Further research will be required to identify which patients will derive the most benefit from combination treatment and to better determine the optimal timing of upfront RT in relation to nivolumab.

In summary, we found combination nivolumab and upfront RT to be associated with an ORR of 35% in unresectable HCC, substantially higher than that previously reported for nivolumab alone. These findings suggest that RT prior to or at the time of nivolumab initiation may enhance the benefit of immune checkpoint inhibition in unresectable HCC. Given the limitations in our data and our small sample size, we view these results as hypothesis generating and recommend the development of prospective clinical trials incorporating upfront RT with nivolumab to more rigorously address this question.

Disclosure statement

Heather M. McGee: Advisory Board-AstraZeneca; Research Grant-Adaptive Biotechnologies.

References

- Global Burden of Disease Liver Cancer C, Akinyemiju T, Abera S, et al. The burden of primary liver cancer and underlying etiologies from 1990 to 2015 at the global, regional, and national level: results from the global burden of disease study 2015. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(12):1683–1691.

- Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, et al. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(4):378–390.

- Kudo M, Finn RS, Qin S, et al. Lenvatinib versus sorafenib in first-line treatment of patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomised phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2018;391(10126):1163–1173.

- Blanchet B, Billemont B, Barete S, et al. Toxicity of sorafenib: clinical and molecular aspects. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2010;9(2):275–287.

- NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Hepatobiliary Cancers. 2019; [cited 2019 Mar 18]. Available from: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/hepatobiliary.pdf.

- El-Khoueiry AB, Sangro B, Yau T, et al. Nivolumab in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (CheckMate 040): an open-label, non-comparative, phase 1/2 dose escalation and expansion trial. Lancet. 2017;389(10088):2492–2502.

- Gong X, Li X, Jiang T, et al. Combined radiotherapy and anti-PD-L1 antibody synergistically enhances antitumor effect in non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2017;12(7):1085–1097.

- Deng L, Liang H, Burnette B, et al. Irradiation and anti-PD-L1 treatment synergistically promote antitumor immunity in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 2014;124(2):687–695.

- Kim KJ, Kim JH, Lee SJ, et al. Radiation improves antitumor effect of immune checkpoint inhibitor in murine hepatocellular carcinoma model. Oncotarget. 2017;8(25):41242–41255.

- Golden EB, Apetoh L. Radiotherapy and immunogenic cell death. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2015;25(1):11–17.

- Vanpouille-Box C, Pilones KA, Wennerberg E, et al. In situ vaccination by radiotherapy to improve responses to anti-CTLA-4 treatment. Vaccine. 2015;33(51):7415–7422.

- Shaverdian N, Lisberg AE, Bornazyan K, et al. Previous radiotherapy and the clinical activity and toxicity of pembrolizumab in the treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer: a secondary analysis of the KEYNOTE-001 phase 1 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(7):895–903.

- Theelen W, Peulen HMU, Lalezari F, et al. Effect of pembrolizumab after stereotactic body radiotherapy vs pembrolizumab alone on tumor response in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer: results of the PEMBRO-RT phase 2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5(9):1276.

- Smith WH, McGee HM, Schwartz M, et al. The safety of nivolumab in combination with prior or concurrent radiation therapy among patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2019;105(1):E227–E228.

- Lencioni R, Llovet JM. Modified RECIST (mRECIST) assessment for hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin Liver Dis. 2010;30(1):52–60.

- Kudo M, Matilla A, Santoro A, et al. Checkmate-040: Nivolumab (NIVO) in patients (pts) with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (aHCC) and Child-Pugh B (CPB) status. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(4_suppl):327–327.

- Barker CA, Postow MA, Khan SA, et al. Concurrent radiotherapy and ipilimumab immunotherapy for patients with melanoma. Cancer Immunol Res. 2013;1(2):92–98.

- Lencioni R, Montal R, Torres F, et al. Objective response by mRECIST as a predictor and potential surrogate end-point of overall survival in advanced HCC. J Hepatol. 2017;66(6):1166–1172.

- Antonia SJ, Lopez-Martin JA, Bendell J, et al. Nivolumab alone and nivolumab plus ipilimumab in recurrent small-cell lung cancer (CheckMate 032): a multicentre, open-label, phase 1/2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(7):883–895.

- Larkin J, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gonzalez R, et al. Combined Nivolumab and Ipilimumab or Monotherapy in Untreated Melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(1):23–34.

- Kaseb AO, Pestana RC, Vence LM, et al. Randomized, open-label, perioperative phase II study evaluating nivolumab alone versus nivolumab plus ipilimumab in patients with resectable HCC. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(4_suppl):185–185.

- Wolchok JD, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gonzalez R, et al. Overall survival with combined nivolumab and ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(14):1345–1356.

- Seung SK, Curti BD, Crittenden M, et al. Phase 1 study of stereotactic body radiotherapy and interleukin-2-tumor and immunological responses. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4(137):137ra74.

- Sato Y, Watanabe H, Sone M, et al. Tumor response evaluation criteria for HCC (hepatocellular carcinoma) treated using TACE (transcatheter arterial chemoembolization): RECIST (response evaluation criteria in solid tumors) version 1.1 and mRECIST (modified RECIST): JIVROSG-0602. Ups. J. Med. Sci. 2013;118(1):16–22.