Abstract

Background

Patients with colon cancer (CC) with low socioeconomic position (SEP) have a worse survival than patients with high SEP. We investigated the association between different socioeconomic indicators and the steps in the treatment trajectory leading to initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy (ACT) for patients with stage III CC.

Materials and Methods

A systematic review and meta-analyses were conducted in accordance with the MOOSE checklist. MEDLINE and EMBASE were searched for eligible studies. Meta-analyses were performed on the separate socioeconomic indicators with the random-effects model. The heterogeneity across studies was assessed by the Q and the I2 statistic.

Results

In total, 27 observational studies were included. SEP was measured by insurance, income, poverty, employment, education, or an index on an area or individual level. SEP, regardless of indicator, was negatively associated with the steps in the treatment trajectory leading to initiation of ACT among patients with resected stage III CC. The meta-analyses showed that patients with low SEP had a significantly lower odds of receiving ACT and increased odds of delayed treatment start, whereas SEP had no impact on the choice of therapy: combination or single-agent therapy.

Conclusion

SEP was associated with less initiation of and higher risk for delayed initiation of ACT. Our findings suggest there is a social disparity in receipt of ACT in patients with stage III CC.

Introduction

Socioeconomic position (SEP) is known to be associated with cancer survival [Citation1,Citation2]. Patients with colorectal cancer (CRC) with low SEP also have lower survival compared

with patients with high SEP [Citation2]. SEP refers to the social and economic factors that influence an individual or group’s position in society [Citation3] and is thought to influence cancer outcomes through patients’ health behaviour [Citation4] and adherence to treatment [Citation5]. Socioeconomic indicators such as education, employment, income and poverty measure different but often related aspects of SEP and may be used to analyse different health outcomes [Citation3].

Several factors may contribute to the observed disparities in cancer survival. Patients with low SEP tend to present with late-stage cancer [Citation6], with a higher risk of metastatic disease and emergency surgery, consequently leading to a poorer prognosis [Citation7]. Furthermore, comorbidity is more common in patients with low SEP, which in itself may have a negative impact on survival [Citation8]. However, suboptimal treatment of patients with low SEP may also be one of the reasons for the socioeconomic disparity in survival of CRC [Citation9].

CRC is the fourth most common cancer worldwide, with about 1.1 million new cases and almost 550,000 deaths in 2018 [Citation10]. In Western countries, the mortality has decreased over the past decades [Citation11]. However, better survival is most pronounced in high-income patients, and the survival gap between patients with low and high SEP seems to have increased during the last 25 years [Citation2].

Primary treatment for local or locally advanced colon cancer (CC) stages I, II and III is a radical resection. Depending on different surgical techniques, tumour stage and risk factors, 4-year disease-free survival (DFS) is 67.5–100% [Citation12]. Adjuvant chemotherapy (ACT) with 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) or capecitabine after surgery for CC was introduced almost 30 years ago [Citation13,Citation14] and is known to reduce the recurrence rate and improve survival for CC stages II–III [Citation15,Citation16].

Combination chemotherapy, with 5-FU/capecitabine + oxaliplatin, has an additional beneficial effect on recurrence and survival [Citation17–19] compared with single-agent therapy and is considered standard therapy for patients with stage III CC, but the addition of oxaliplatin increases risk of toxicity [Citation18] especially in older patients and patients with comorbidity. Despite consensus regarding adjuvant treatment, many patients do not receive ACT due to high age, comorbidity or poor performance status [Citation20]. This is undoubtedly because treatment decisions are undertaken after an individual assessment of the patient including estimation of the risk of toxicity and even treatment-related death.

Previously, reviews from 2008 and 2010 have suggested an association between low SEP and poorer treatment outcomes for patients with CRC [Citation9,Citation20]; however, most studies included patients treated before oxaliplatin was used in the adjuvant setting. Furthermore, there has also been an increased focus on how SEP is associated with treatment outcomes in CRC, and thus, there is a need of updated evaluation including newer studies. In the present review, we summarise the available evidence for the associations between different socioeconomic indicators and the initiation of ACT only in patients with resected stage III CC, a group of patients where there is no question about treatment indication.

We hypothesised that patients with low SEP are less likely to be assessed for treatment by an oncologist (oncological assessment), to be offered and to accept ACT, and are more likely to experience delay before treatment start. We also hypothesised that patients with low SEP were less likely to receive combination therapy instead of single-agent therapy.

Materials and methods

We undertook a systematic review and meta-analysis applying the MOOSE guidelines [Citation21] (for PRISMA checklist specific to this report see Supplementary Table 1) to evaluate the association between SEP and the steps leading to initiation of ACT in patients with stage III CC. The protocol was registered at PROSPERO (registration number: CRD42019118277).

Eligibility criteria

For this study, we considered the following SEP measures: insurance, income, poverty, employment, education or an SEP index measured on the area-based or the individual level. Studies were chosen that evaluated the different steps in the treatment trajectory leading to initiation of ACT as primary or secondary outcomes: (1) studies which included all patients who had a surgical resection for stage III CC and (2) studies which only included patients who also had an oncological assessment for ACT.

Studies were excluded if data were based on questionnaires or if data were only preliminary. Studies with sample size < 100 patients or studies where data for stage III CC patients could not be isolated and extracted were also excluded. If data were published more than once, the most recent study was selected. When several studies were based on the same study population, the larger study was selected. However, if two studies, based on the same patient material had different settings at study entry (e.g., patients with only resected stage III CC vs. patients who also had a postoperative consultation with an oncologist), they were included even if the same outcome was reported.

Search strategy

Included studies were identified via systematic search in two electronic databases: Medline and EMBASE. References of included publications were reviewed to identify additional citations. Searches were limited to human studies, English language, available full-text manuscripts and publication after 1 January 1990. The search was performed on 14 August 2019 (for detailed search, see Supplementary Table 2).

Study selection

Two independent researchers (AK and DN) reviewed all titles and abstracts to identify potentially relevant studies. All relevant manuscripts were screened as full text by the two authors (AK and DN). Disagreements were discussed at a consensus meeting with a third reviewer (CL).

Data extraction

For studies included in this work, the following data were extracted: study characteristics including author, country, inclusion period and the number of patients, SEP and outcomes. The results were extracted in available measurements: raw numbers, percentage, odds ratio (OR), adjusted OR (AOR), relative risk (RR) and adjusted RR (ARR) followed by 95% confidence intervals (CIs) or p values.

Quality assessment

There is no single recommended tool for assessing the quality of observational studies [Citation22]. Therefore, we assessed the quality of studies based on the following factors: clear study objectives and description of data source, eligibility criteria, study sample, age characteristics, definition of SEP and study limitations as well as adjustments of risk estimates. The overall assessment (H = high quality or C = some concerns) was decided in the author group (AK, CL, DN, SD) (see Supplementary Table 2).

Outcome measures

The primary outcome was the initiation of ACT, and the secondary outcomes were combination therapy vs. monotherapy, delayed initiation of ACT, having a consultation with an oncologist, and a doctor’s recommendation of and a patient’s acceptance of ACT.

Data analysis

We used random effect models, with the inverse variance method, to estimate the overall pooled OR and associated 95% confidence interval (CI) for the association between SEP and the steps in the treatment trajectory leading to initiation of ACT. As different socioeconomic indicators cover different but partially overlapping aspects of SEP, no overall meta-analysis was conducted, but separate meta-analyses were performed for each socioeconomic indicator. The overall pooled estimates were computed by using the most complete available estimate from each study: OR adjusted for confounders, non-adjusted OR or calculated OR based on reported raw numbers.

Standard errors (SEs) for the meta-analyses were obtained from CIs (SE = (upper limit– lower limit)/3.92) and p values (SE = effect estimate / Z) [Citation23]. Heterogeneity was evaluated by means of Q test and I2 statistics if a sufficient number of studies were included in the meta-analysis [Citation24]. The I2 value of 0% indicated no heterogeneity, and a value closer to 100% indicated considerable heterogeneity between studies [Citation25].

All analyses were conducted with the statistical software R version 3.4.1 (‘meta’ package) [Citation26] using a 5% significance level. Calculations and meta-analyses were performed by AK and supervised by VA.

Results

Study characteristics

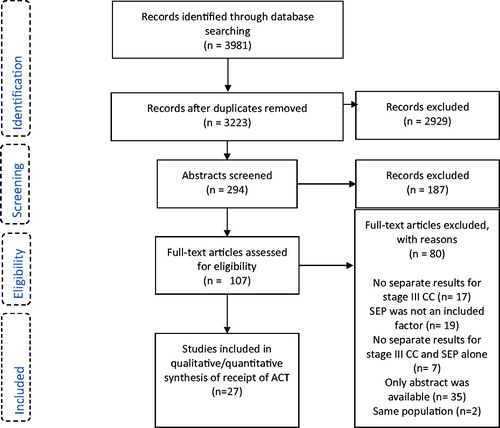

The systematic literature search identified 3223 citations. A total of 107 studies were reviewed in full text, and after the exclusion of 80 manuscripts, 27 studies (462,371 patients) were included in this review and meta-analysis [Citation27–53] (). For details on search and exclusion, see .

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of included trials, SEP indicators and use of adjuvant chemotherapy.

All included studies but one were retrospective observational studies primarily based on register data [Citation27–50] or data from medical records [Citation28,Citation34,Citation36,Citation37,Citation51,Citation52]. One prospective study was included [Citation53]. Most of the studies were North American (US [Citation27–33,Citation35,Citation38,Citation41–44,Citation46,Citation48 Citation49,Citation51,Citation52] or Canadian [Citation34,Citation36,Citation37,Citation47]). The rest were European (the Netherlands [Citation39,Citation40,Citation50], Sweden [Citation45] and Spain [Citation53]).

In general, the study quality was good, although differences existed in study objectives, description of SEP, and in one study no limitations were described (Supplementary Table 3). Patients were diagnosed with CC between 1991 to 2014, and the number of patients included in the studies ranged from 303 to 196,412. Most studies included patients of all ages. However, six studies only included patients above 65 years [Citation33,Citation38,Citation39,Citation41,Citation42,Citation46], and others introduced an age limit [Citation39,Citation45]. Most US studies included race in patient characteristics but reported results on the entire population [Citation27–29,Citation32,Citation35,Citation38,Citation41,Citation42,Citation44,Citation51,Citation52]. However, Baldwin et al. reported data on black and white races separately, and data on both were included in the analyses [Citation41].

As stated in the method section, the studies included patients in two different settings at study entry: (1) All patients who had surgical resection of stage III CC (23 studies) [Citation27–36,Citation38–40,Citation42–45,Citation47,Citation48,Citation50–53] and (2) Patients with resected stage III CC who also had an oncological assessment for ACT (four studies) [Citation37,Citation41,Citation46,Citation49]. Two of the studies only included patients who received ACT and investigated the association between SEP and delay of treatment [Citation46,Citation49].

We evaluated three groups of socioeconomic indicators and their association with initiation of ACT: (1) Economic resources using four different indicators, insurance [Citation27–32,Citation51,Citation52], income [Citation27,Citation29,Citation33–38,Citation41,Citation48], SEP index [Citation39,Citation40,Citation53] and poverty [Citation30,Citation42–44,Citation51]; (2) employment [Citation36,Citation37,Citation41,Citation52] and 3) education [Citation29,Citation33,Citation36,Citation37,Citation41,Citation45]. For the primary outcome, results are presented by study entry; while results for secondary outcomes are presented regardless of patient setting

Primary outcome: initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy

Studies including patients with resected stage III CC at study entry (23 studies)

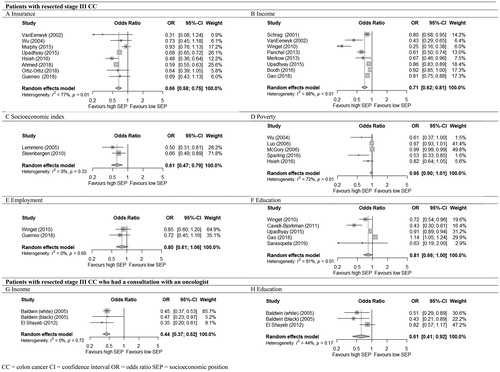

Economic resources: The association between initiation of ACT and SEP in relation to economic resources, i.e., insurance, income, socioeconomic index or poverty, was evaluated in . Overall the meta-analyses showed that patients with a low level of economic resources were less likely to receive ACT compared to patients with a high level of economic resources. We pooled data from eight studies for the meta-analysis evaluating insurance (334,207 patients) and income (219,476 patients). The meta-analysis evaluating insurance showed that patients with public or no insurance had a 34% reduced odds of receiving ACT compared to patients with private insurance (OR = 0.66; 95% CI = 0.58–0.75) [Citation27–32,Citation51,Citation52]. Patients with low income were likewise less likely to receive ACT (OR = 0.71; 95 % CI = 0.62–0.81) [Citation27,Citation29,Citation33–36,Citation38,Citation48]. The heterogeneity across the studies was considerable and significant in both meta-analyses (I2 = 98% and 88%, p < .01). For the socioeconomic index, the pooled results from only two studies were significant (OR = 0.61; 95% CI = 0.47–0.79, 2214 patients). Finally, the meta-analysis of five studies (17,406 patients) evaluating poverty did not reach statistical significance (OR = 0.95; 95% CI = 0.90–1.01) [Citation30,Citation42–44,Citation51] and the heterogeneity across studies was substantial (I2 = 72%, p < .01) ().

Figure 2. Meta-analyses of receiving adjuvant chemotherapy in low versus high socioeconomic position among patients with resected stage III colon cancer (CC) (A–F) and stage III CC patients with an oncological assessment (G,H). CC: colon cancer; CI: confidence interval; OR: odds ratio; SEP: socioeconomic position.

Employment: The meta-analysis of two studies (1210 patients) compared patients from areas with high and low level of employment showed lower odds of receiving treatment for patients living in an area with a low level of employment; however, the finding did not reach statistical significances (OR = 0.80; 95% CI = 0.61–1.06) [Citation36,Citation52] ().

Education: In the five studies (222,044 patients) evaluating education, meta-analysis showed lower odds for receiving ACT among patients with low education level; however, the pooled estimate did not reach statistical significance (OR = 0.81; 95 % CI = 0.66–1.00) [Citation29,Citation33,Citation36,Citation45,Citation53]. The heterogeneity was considerable and significant (I2 = 91 %, p < 0.01) ().

Studies including patients who also have had an oncological assessment at study entry (four studies)

Economic resources: In the meta-analysis of two studies (24,778 patients), one study contributing with two separate sub-group estimates, we found patients living in an area with a low income less likely to receive ACT compared to patients living in an area with a high income (OR = 0.44; 95% CI = 0.37–0.52) [Citation37,Citation41]) ()

Employment: No included studies.

Education: The meta-analysis of two studies (24,778 patients), one study contributing with two separate sub-group estimates, showed a significant decrease in odds of receipt of ACT for patients with low educational level compared to patients with higher education level (OR = 0.61; 95% CI = 0.41–0.92) [Citation37,Citation41] ().

Secondary outcomes

Consultation with an oncologist in studies including patients with resected stage III CC at study entry

Economic resources: The association between SEP and having an oncologic consultation for ACT was analysed in two studies including patients with resected stage III CC [Citation36,Citation42]. Due to the lack of overlap in socioeconomic indicators results could not be pooled for meta-analysis. Patients living in a low-income area had an increased risk of not meeting an oncologist (adjusted rate ratio (ARR) = 2.05; 95% CI = 1.21–3.45; 772 patients) [Citation36]; whereas poverty did not alter the risk of not having an oncology consultation (ARR = 0.99; 95% CI = 0.96–1.02; 7569 patients) [Citation42].

Recommendation and accept of adjuvant chemotherapy

Economic resources, employment, education: One study of 613 patients who had an oncological assessment analysed the association between SEP and oncologists’ recommendations and patients acceptance of ACT. Patients living in an area with a low income or low level of employment were less likely to have ACT recommended and to accept ACT compared to patients living an area with a high income (p = .01) or high level of employment (p = .04). The result for the educational level was insignificant (p = .50) [Citation37].

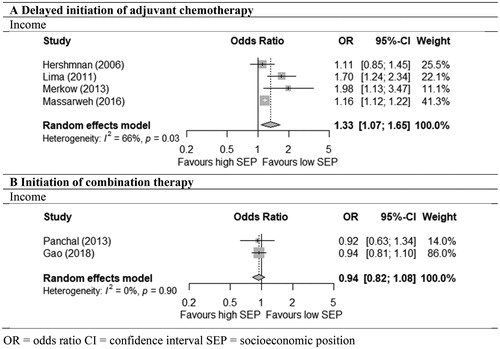

Delayed initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy

Economic resources, socioeconomic index: Four studies analysed the timing of ACT. We pooled the four studies (two studies including patients with resected CC [Citation47,Citation48] and two studies including patients who all received ACT [Citation46,Citation49]) on income, which described delayed initiation of ACT (defined as beyond 60 days to 3 months). Patients living in low-income areas were 33% more likely to experience delay than patients living in high-income areas (OR = 1.33; 95% CI = 1.07–1.65, (59,134 patients)) () [Citation46–49]. The heterogeneity across the studies was substantial and significant (I2 = 66 %, p = .03). The fifth study including patients who all received ACT (606 patients) showed that patients living in an area with a low socioeconomic index had a reduced likelihood of delayed initiation of ACT (AOR = 0.32; 95% CI = 0.13–0.76) [Citation50].

Figure 3. Meta-analyses of odds of delayed initiation of chemotherapy (A) and of initiation of combination chemotherapy (B) in low versus high socioeconomic position (SEP) among stage III colon cancer patients. OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval; SEP: socioeconomic position.

Initiation of combination therapy vs. monotherapy

Economic resources: Three studies including patients after resection [Citation31,Citation33,Citation35] analysed the association between income or insurance and the initiation of combination or single-agent therapy: 5-FU/ capecitabine +/÷ oxaliplatin. The administration of combination therapy did not differ significantly between patients with low and high income (OR = 0.94; 95% CI = 0.82–1.08) (two studies; 22,597 patients) [Citation33,Citation35] (). The only study on insurance (1035 patients) compared patients with private insurance to patients with Medicaid insurance and showed a similar result (AOR = 1.57; 95% CI = 0.95–2.58) [Citation31].

Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analyses investigating the effect of SEP on the initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy for patients with stage III CC showed that low SEP is negatively associated with the steps in the treatment trajectory that lead to the initiation of ACT among patients with resected stage III CC.

For all investigated socioeconomic indicators, insurance, income, socioeconomic index, poverty, employment and education, the evidence for an effect on the initiation of ACT was weak. Evidence was rated as weak due to the relatively low number of trials included, and the heterogeneity among the trials. with low SEP had significantly lower odds of receiving ACT and increased odds of delayed initiation of ACT; whereas SEP was not found to have a significant impact on the choice of regimen, i.e., combination therapy vs. single-agent therapy. The results were generally consistent across the different socioeconomic indicators and definitions of the study population. The present review included studies from the US, Canada and Europe and findings also appear consistent across countries and time periods, even though this was not formally analysed. Our summary of available studies points towards social disparity in receipt of adjuvant therapy among patients with stage III CC, leading to potential under-treatment of certain patient groups. This is in line with previous reviews showing a socioeconomic disparity regarding the adjuvant treatment of patients with CRC [Citation9,Citation20,Citation54].

Interpretation of results

Considerations regarding initiation of ACT involve both tumour-related factors and patient-related factors such as comorbidities, performance status and the patients’ individual preferences [Citation55]. In this review, we included only patients with stage III CC, for whom guidelines worldwide recommend postoperative ACT to eliminate stage as a prognostic tumour-related factor for non-initiation. Thus, differences in stage at diagnosis cannot explain the disparities in the initiation of ACT. Our finding that patients with low SEP had a lower likelihood of receiving antineoplastic treatment is in accordance with treatment disparities seen in, e.g., patients with early-stage lung cancer [Citation56].

Severe comorbidity is a relative contraindication for ACT, and patients with comorbidities have poorer prognosis possibly because of a lack of treatment guidelines for patients with comorbidity. Thus, many patients receive unnecessarily modified potentially curative treatment [Citation8]. Hence, treatment disparities might be due to SEP-related differences in comorbidity at diagnosis. On the other hand, no treatment could in fact be the best choice for some patients due to the high risk of toxicity and treatment-related death. An older study has shown a less clear association between SEP and the number of comorbidities at diagnosis for patients with CRC [Citation57] compared with patients diagnosed with breast or lung cancer; however, data were based on a relatively small number (384) of patients diagnosed in 1993.

Our study shows that SEP may play a role in treatment decision-making. One included study showed that patients living in areas with low income or employment were less likely to be offered and accept ACT [Citation37]. This is in line with a study by Ayanian et al., who showed that 30% of patients with early-stage CRC living in the low-income areas refused the recommended ACT [Citation58]. However, the underlying reasons for the finding could not be explored but may be due to the risk of functional decline and dependence during treatment combined with the lack of financial or social resources, all of which are factors that may be differentially distributed due to SEP [Citation59,Citation60]. Furthermore, the observed differences between patients with low and high SEP could also be due to the communication between physician and patient. A review showed that physicians tend to alter their communication style in consultations with patients with low SEP; the patients were provided with less information and relatively more time was spent on physical examination, and patients tend to be less involved in the treatment decision [Citation61]. Awareness and training in communication strategy with attention to differences in resources and health literacy may support patients with low SEP in the treatment decision process.

The growing evidence on socioeconomic differences in cancer treatment delivery calls for attention to the identification of patients who are at risk of sub-optimal assessment and treatment – and to the development of interventions that may provide more equitable care. However, the reasons for less initiation of chemotherapy could not be explored in the included retrospective studies. There is a need of more in-depth evaluations including qualitative studies of patients and physicians to explore reasons for acceptance or decline of examination and treatment.

Several points of action have already been targeted. Examples include patient education and navigation to improve health literacy and patient involvement in treatment planning and adherence [Citation62], optimisation of patients’ comorbid conditions or prehabilitation of high-risk patients, which so far have predominantly been tested in the surgical cancer setting [Citation63,Citation64]. However, we need in-depth knowledge of the core of the problem to develop feasible and patient-centred evidence-based interventions that may secure optimal treatment possibilities for all patients, regardless of SEP, and thus reduce disparities in cancer care.

Strengths and limitations

In this review we have explored the evidence regarding socioeconomic disparity in cancer care by providing an updated review of a comprehensive range of social indicators and undertaking meta-analyses of available results of patients resected for stage III CC. All studies but one were based on retrospective data. Such studies entail both strengths and challenges One strength is the ability to assess the process and outcomes of routine care [Citation65], challenges include the potential missing information. Limitations include heterogeneous pooled data. Thus, the meta-analyses were challenged by the differences across the individual studies: differences in design, inconsistent adjustments of covariates and heterogeneity of the populations regarding sociodemographics (e.g., SEP, age, race and comorbidity), the available estimations for extraction from each study (e.g., unadjusted OR, adjusted OR, OR calculated from raw numbers), and in the definition of the outcomes. Regarding differences in adjustments of estimates, more than half were adjusted for multiple factors of known association to both socioeconomic position and receipt and timeliness of cancer treatment. In general, the adjusted estimates were not very dissimilar from the unadjusted estimates within those studies that presented both, indicating robustness of findings. Some of the reviewed studies defined all chemotherapy initiated within 6–12 months after surgery as ACT although it could be palliative, and the cut off defining delayed initiation of ACT varied from 60 days to 3 months.

SEP can be measured, categorised and linked to patients in various ways, which can create some heterogeneity [Citation3,Citation66,Citation67]. Furthermore, most reviewed studies measured SEP on an area level, while insurance [Citation27–32,Citation51,Citation52], employment [Citation52] and education [Citation45] were measured on an individual level. When SEP is measured on an area level and then used as a proxy for SEP on an individual level, the estimate of the association between SEP and the outcome might be an underestimation of the true effect [Citation67].

By only including the subgroup of patients with stage III CC and by grouping the socioeconomic indicators, data were made more homogeneous. However, in 5 out of 10 meta-analyses, substantial heterogeneity might be present (I2 > 50 %). Furthermore, the low number of studies in each meta-analysis precluded further examination of heterogeneity, with, e.g., additional subgroup analyses. The low number of studies also precluded formal evaluation of publication bias, as the power of the tests would be too low to distinguish chance from real asymmetry. Our results should therefore be interpreted with caution. Insignificant results of the association between SEP and the steps in the treatment trajectory leading to initiation of ACT might not have been reported or might be unextractable for meta-analyses.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the present systematic review and meta-analyses show socioeconomic disparities in the treatment of patients with resected stage III CC. Patients with low SEP were less likely to receive adjuvant chemotherapy compared to patients with high SEP.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (30.5 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (13.2 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (107.1 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Woods LM, Rachet B, Coleman MP. Origins of socio-economic inequalities in cancer survival: a review. Ann Oncol. 2006;17(1):5–19.

- Dalton SO, Olsen MH, Johansen C, et al. Socioeconomic inequality in cancer survival - changes over time. A population-based study, Denmark, 1987–2013. Acta Oncol. 2019;58(5):737–744.

- Galobardes B, Shaw M, Lawlor DA, et al. Indicators of socioeconomic position (part 1). J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60(1):7–12.

- Williams-Brennan L, Gastaldo D, Cole DC, Paszat L. Social determinants of health associated with cervical cancer screening among women living in developing countries: a scoping review. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2012;286(6):1487–1505.

- Gast A, Mathes T. Medication adherence influencing factors-an (updated) overview of systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2019;8(1):112

- Singer S, Roick J, Briest S, et al. Impact of socio-economic position on cancer stage at presentation: findings from a large hospital-based study in Germany. Int J Cancer. 2016;139(8):1696–1702.

- Bayar B, Yilmaz KB, Akinci M, et al. An evaluation of treatment results of emergency versus elective surgery in colorectal cancer patients. UCD. 2016;32(1):11–17.

- Sarfati D, Koczwara B, Jackson C. The impact of comorbidity on cancer and its treatment. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(4):337–350.

- Aarts MJ, Lemmens VE, Louwman MW, et al. Socioeconomic status and changing inequalities in colorectal cancer? A review of the associations with risk, treatment and outcome. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46(15):2681–2695.

- Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, et al. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6):394–424.

- Arnold M, Sierra MS, Laversanne M, et al. Global patterns and trends in colorectal cancer incidence and mortality. Gut. 2017;66(4):683–691.

- Bertelsen CA, Neuenschwander AU, Jansen JE, et al. Disease-free survival after complete mesocolic excision compared with conventional colon cancer surgery: a retrospective, population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(2):161–168.,

- Laurie JA, Moertel CG, Fleming TR, et al. Surgical adjuvant therapy of large-bowel carcinoma: an evaluation of levamisole and the combination of levamisole and fluorouracil. J Clin Oncol. 1989;7(10):1447–1456.

- Moertel CG, Fleming TR, Macdonald JS, et al. Levamisole and fluorouracil for adjuvant therapy of resected colon carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1990;322(6):352–358.

- Gill S, Loprinzi CL, Sargent DJ, et al. Pooled analysis of fluorouracil-based adjuvant therapy for stage II and III colon cancer: who benefits and by how much?. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(10):1797–1806.

- Gray R, Barnwell J, McConkey C, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy versus observation in patients with colorectal cancer: a randomised study. Lancet. 2007;370(9604):2020–2029.

- Andre T, Boni C, Navarro M, et al. Improved overall survival with oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin as adjuvant treatment in stage II or III colon cancer in the MOSAIC trial. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(19):3109–3116.

- Yothers G, O'Connell MJ, Allegra CJ, et al. Oxaliplatin as adjuvant therapy for colon cancer: updated results of NSABP C-07 trial, including survival and subset analyses. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(28):3768–3774.

- Haller DG, Tabernero J, Maroun J, et al. Capecitabine plus oxaliplatin compared with fluorouracil and folinic acid as adjuvant therapy for stage III colon cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(11):1465–1471.

- Etzioni DA, El-Khoueiry AB, Beart RW. Jr. Rates and predictors of chemotherapy use for stage III colon cancer: a systematic review. Cancer. 2008;113(12):3279–3289.

- Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000;283(15):2008–2012.

- Sanderson S, Tatt ID, Higgins JP. Tools for assessing quality and susceptibility to bias in observational studies in epidemiology: a systematic review and annotated bibliography. Int J Epidemiol. 2007;36(3):666–676.

- Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Cochrane book series. The Cochrane Collaboration. Wiley; 2008. p. 174–175.

- Deeks JJ, Higgins JPT, Altman DG (editors). Chapter 10: Analysing data and undertaking meta-analyses. In: Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA, editors. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 6.0. Cochrane; 2019 [updated 2019 Jul]. Available from: www.training.cochrane.org/handbook

- Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Cochrane book series. The Cochrane Collaboration. 2008. p. 277–278.

- RStudio Team. 2015. RStudio: Integrated Development for R. Boston, MA: RStudio, Inc. Available from: http://www.rstudio.com

- VanEenwyk J, Campo JS, Ossiander EM. Socioeconomic and demographic disparities in treatment for carcinomas of the colon and rectum. Cancer. 2002;95(1):39–46.

- Murphy CC, Harlan LC, Warren JL, et al. Race and insurance differences in the receipt of adjuvant chemotherapy among patients with stage III colon cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(23):2530–2536.

- Upadhyay S, Dahal S, Bhatt VR, et al. Chemotherapy use in stage III colon cancer: a National Cancer Database analysis. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2015;7(5):244–251.

- Hsieh MC, Thompson T, Wu XC, et al. The effect of comorbidity on the use of adjuvant chemotherapy and type of regimen for curatively resected stage III colon cancer patients. Cancer Med. 2016;5(5):871–880.

- Ortiz-Ortiz KJ, Tortolero-Luna G, Rios-Motta R, et al. Use of adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with stage III colon cancer in Puerto Rico: a population-based study. PLOS One. 2018;13(3):e0194415.

- Ahmed A, Tahseen A, England E, et al. Association between primary payer status and survival in patients with stage III colon cancer: an National Cancer Database Analysis. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2019;18(1):e1–e7.

- Gao P, Huang XZ, Song YX, et al. Impact of timing of adjuvant chemotherapy on survival in stage III colon cancer: a population-based study. BMC Cancer. 2018;18(1):234.

- Booth CM, Nanji S, Wei X, et al. Use and effectiveness of adjuvant chemotherapy for stage III colon cancer: a population-based study. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2016;14(1):47–56.

- Panchal JM, Lairson DR, Chan W, et al. Geographic variation and sociodemographic disparity in the use of oxaliplatin-containing chemotherapy in patients with stage III colon cancer. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2013;12(2):113–121.

- Winget M, Hossain S, Yasui Y, et al. Characteristics of patients with stage III colon adenocarcinoma who fail to receive guideline-recommended treatment. Cancer. 2010;116(20):4849–4856.

- El Shayeb M, Scarfe A, Yasui Y, et al. Reasons physicians do not recommend and patients refuse adjuvant chemotherapy for stage III colon cancer: a population based chart review. BMC Res Notes. 2012; 5:269

- Schrag D, Cramer LD, Bach PB, et al. Age and adjuvant chemotherapy use after surgery for stage III colon cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93(11):850–857.

- Lemmens VE, van Halteren AH, Janssen-Heijnen ML, et al. Adjuvant treatment for elderly patients with stage III colon cancer in the southern Netherlands is affected by socioeconomic status, gender, and comorbidity. Ann Oncol. 2005;16(5):767–772.

- van Steenbergen LN, Rutten HJ, Creemers GJ, et al. Large age and hospital-dependent variation in administration of adjuvant chemotherapy for stage III colon cancer in southern Netherlands. Ann Oncol. 2010;21(6):1273–1278.

- Baldwin LM, Dobie SA, Billingsley K, et al. Explaining black-white differences in receipt of recommended colon cancer treatment. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97(16):1211–1220.

- Luo R, Giordano SH, Freeman JL, et al. Referral to medical oncology: a crucial step in the treatment of older patients with stage III colon cancer. Oncologist. 2006;11(9):1025–1033.

- McGory ML, Zingmond DS, Sekeris E, et al. A patient's race/ethnicity does not explain the underuse of appropriate adjuvant therapy in colorectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006; 49:319–329.

- Sparling AS, Song E, Klepin HD, et al. Is distance to chemotherapy an obstacle to adjuvant care among the N.C. Medicaid-enrolled colon cancer patients?. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2016;7(3):336–344.

- Cavalli-Bjorkman N, Lambe M, Eaker S, et al. Differences according to educational level in the management and survival of colorectal cancer in Sweden. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47(9):1398–1406.

- Hershman D, Hall MJ, Wang X, et al. Timing of adjuvant chemotherapy initiation after surgery for stage III colon cancer. Cancer. 2006;107(11):2581–2588.

- Lima IS, Yasui Y, Scarfe A, et al. Association between receipt and timing of adjuvant chemotherapy and survival for patients with stage III colon cancer in Alberta, Canada. Cancer. 2011;117(16):3833–3840.

- Merkow RP, Bentrem DJ, Mulcahy MF, et al. Effect of postoperative complications on adjuvant chemotherapy use for stage III colon cancer. Ann Surg. 2013; 258:847–853.

- Massarweh NN, Haynes AB, Chiang YJ, et al. Adequacy of the National Quality Forum's Colon Cancer Adjuvant Chemotherapy Quality Metric: is 4 months soon enough?. Ann Surg. 2015;262(2):312–320.

- van der Geest LG, Portielje JE, Wouters MW, et al. Complicated postoperative recovery increases omission, delay and discontinuation of adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with Stage III colon cancer. Colorectal Dis. 2013;15(10):e582–591.

- Wu X, Chen VW, Andrews PA, et al. Treatment patterns for stage III colon cancer and factors related to receipt of postoperative chemotherapy in Louisiana. J La State Med Soc. 2004;156(5):255–261.

- Guerrero W, Wise A, Lim G, et al. Better Late than Never? Adherence to adjuvant therapy guidelines for stage III colon cancer in an underserved region. J Gastrointest Surg. 2018;22(1):138–145.

- Sarasqueta C, Perales A, Escobar A, et al. Impact of age on the use of adjuvant treatments in patients undergoing surgery for colorectal cancer: patients with stage III colon or stage II/III rectal cancer. BMC Cancer. 2019;19(1):735.

- Malietzis G, Mughal A, Currie AC, et al. factors implicated for delay of adjuvant chemotherapy in colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22(12):3793–3802.

- Labianca R, Nordlinger B, Beretta GD, et al. Early colon cancer: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2013;24(Suppl 6):vi64–72.

- Forrest LF, Adams J, Wareham H, et al. Socioeconomic inequalities in lung cancer treatment: systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2013;10(2):e1001376.

- Schrijvers CT, Coebergh JW, Mackenbach JP. Socioeconomic status and comorbidity among newly diagnosed cancer patients. Cancer. 1997;80(8):1482–1488.

- Ayanian JZ, Zaslavsky AM, Fuchs CS, et al. Use of adjuvant chemotherapy and radiation therapy for colorectal cancer in a population-based cohort. JCO. 2003;21(7):1293–1300.

- Abbott DE, Voils CL, Fisher DA, et al. Socioeconomic disparities, financial toxicity, and opportunities for enhanced system efficiencies for patients with cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2017;115(3):250–256.

- Galvin A, Delva F, Helmer C, et al. Sociodemographic, socioeconomic, and clinical determinants of survival in patients with cancer: a systematic review of the literature focused on the elderly. J Geriatr Oncol. 2018;9(1):6–14.

- Verlinde E, De Laender N, De Maesschalck S, et al. The social gradient in doctor-patient communication. Int J Equity Health. 2012;11:12

- Bernardo BM, Zhang X, Beverly Hery CM, et al. The efficacy and cost-effectiveness of patient navigation programs across the cancer continuum: a systematic review. Cancer. 2019;125(16):2747–2761.

- Rosero ID, Ramirez-Velez R, Lucia A, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials on preoperative physical exercise interventions in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2019;11(7):944.

- Scheede-Bergdahl C, Minnella EM, Carli F. Multi-modal prehabilitation: addressing the why, when, what, how, who and where next?. Anaesthesia. 2019;74(Suppl 1):20–26.

- Huston P, Naylor CD. Health services research: reporting on studies using secondary data sources. CMAJ. 1996;155(12):1697–1709.

- Shavers VL. Measurement of socioeconomic status in health disparities research. J Natl Med Assoc. 2007;99(9):1013–1023.

- Galobardes B, Lynch J, Smith GD. Measuring socioeconomic position in health research. Br Med Bull. 2007; 81-82:21–37.