Abstract

Introduction

Palliative care can reduce the symptom burden and may increase the life expectancy for patients with advanced malignancies. The aim of this study was to evaluate the impact of palliative intervention on the treatment procedures for pancreatic cancer patients during their last month of life.

Material and Methods

This retrospective single-centre study included adult pancreatic cancer patients who were treated in Turku University Hospital during their last month of life and died between 2011 and 2016. Data were collected from hospital database. Oncological treatments, the number of radiological examinations and procedures, surgical procedures, emergency department visits, hospitalisations, the place of death and medical costs were examined in tertiary care for patients with or without contact to the palliative care unit.

Results

From 378 eligible patients, 20% (n = 76) had a contact to the palliative care unit. These patients had less radiological examinations (p < 0.0001), hospitalisations (p <0.0001) and emergency department visits (p = 0.021) during the last month of life. They did not die in the university hospital as often (p = 0.011) and median of their medical costs during the last month of life was approximately half (p <0.0001) when compared to patients with no palliative intervention (n = 302). They had longer overall survival (p <0.0001) which was the only difference detected in the characteristics of the groups.

Conclusion

Fewer treatment procedures and lower tertiary care costs during the last month of life were observed for the pancreatic cancer patients who had a contact to the palliative care unit. Palliative care intervention should be an essential part of the treatment schedule for these patients.

Introduction

Pancreatic cancer is one of the most lethal malignant diseases with an overall survival rate of only 5%−12% at 5 years after the diagnosis [Citation1,Citation2]. In Finland, it is the fourth most common cause of death in cancer among both sexes [Citation3]. Despite many advances in pathology, molecular biology and treatment options, the life expectancy of patients with advanced pancreatic cancer, even after resection with curative-intent is often limited to months [Citation4].

According to ASCO (American Society of Clinical Oncology) guidelines, all patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer should receive palliative care concurrent with active treatment beginning from the first visit to the hospital because of the high symptom burden and short life expectancy [Citation5,Citation6]. Palliative care intervention has not only shown to improve the quality of life and satisfaction with care, but also to extend survival and be associated with less aggressive end-of-life care for patients with advanced malignancies [Citation7–11]. However, there are also studies where no changes in the overall survival have been detected for patients receiving palliative care [Citation12,Citation13].

Palliative care units are still sparse in Finland and regular early palliative intervention for patients with advanced cancer has not been available. Palliative outpatient clinic was established in Turku University Hospital (TUH) in 2005; however, due to scarce resources, more systematic palliative intervention has been available only since 2015.

Although the need for palliative care is obvious for patients with pancreatic cancer, the real life medical interventions and costs of care during the last weeks of life are still unresolved. To evaluate the role of palliative care and change of treatment practises for patients with pancreatic cancer near end of life, we performed a retrospective single-centre study. The main objective was to study the use of hospital services (radiological examinations and procedures, surgical and oncological care and visits to the hospital) and medical costs in tertiary care during the last month of life. We also studied the place of death in regard to whether the patient had a contact to the palliative care unit.

Material and methods

Data sources and cohort selection

TUH is one of the five academic hospitals in Finland. The hospital district has a population of approximately 480 000 people. It is the only hospital in the area that provides oncological and surgical cancer care and all patients with pancreatic cancer in the area are referred to TUH.

In TUH, electronic patient records include systematically documented information on all treated patients. For secondary use, this information has been collected from multiple operative information technology systems and combined with patients´ identity details to form the database of Auria Clinical Informatics. Auria Clinical Informatics organises, harmonises and maintains the data in the data warehouse at the Hospital District of Southwest Finland. Auria also works as a link between the data and the researcher as it provides expert services and patient data for scientific research.

From the database all pancreatic cancer patients (N = 534) treated in TUH and deceased between 2011 and 2016 were identified by using the ICD-10-code C25. Patients with neuroendocrine tumours (ICD-10-code C25.4 or E34) were not included. The authors had full access to the original patient records and data were manually validated by checking the medical records of all 534 patients to ensure the pancreatic cancer diagnose. Secondary malignant tumours in pancreas, e.g., metastasis of melanoma or lymphoma in pancreas, were excluded (n = 72). The data were collected by the Auria Clinical informatics during 2017 and supplementary data during 2019. The validations were performed during autumn 2017 and autumn 2019.

Methods

A total of 462 pancreatic cancer patients deceased during the years 2011–2016. Of these patients, 378 had a contact to the tertiary care during the last 30 days of life and were eligible for the analysis, respectively. To study whether referral to palliative care unit had an effect on the treatment patterns and active interventions during the last month of life, patients were divided into two groups: patients who had a contact to the palliative care unit (n = 76, Palliative Care Group = PC group) and patients who received only standard surgical and/or oncological treatment with no palliative intervention in TUH (n = 302, Standard Care Group = SC group). For most of the patients palliative intervention was an appointment with a doctor and a nurse in a palliative outpatient clinic (n = 73, 96%). If patient was unable to visit the hospital clinic due to the poor physical performance status and persistent symptoms caused by the progression of pancreatic cancer, a call from the clinic was also a possibility (n = 3, 4%). Patients who received only palliative consultation were not included in this PC group. The type of palliative intervention was manually checked from the patient records.

For both groups, patient characteristics, overall survival and the place of death were evaluated. The data on the number of the chemotherapy regimens as well as the total dose of the radiotherapy were also assessed. In addition, during the last month of life (i) Radiological examinations and procedures including X-rays, computer tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), ultrasound examination (US), and other (including stenting and paracentesis), (ii) Surgical procedures, (iii) Emergency department visits and (iv) Hospitalisations in any ward of the university hospital were studied.

For all the patients who had a histological diagnose of” carcinoma” or” adenocarcinoma” in the pathology report 90 days before or any time after the first appearance of a pancreatic cancer diagnose (ICD-10-code C25), the pathology reports were manually checked to clarify the histological verification of the pancreatic cancer diagnose.

Medical costs in the university hospital were available in the database of the Centre of Clinical Informatics for all patients starting from the year 2012 (n = 244 patients). The information was available for 189 patients (63%) in the SC group and for 55 patients (72%) in the PC group. The data regarding the costs of care are based on the hospital invoicing. Hospital charges all hospital treatment costs from the patient´s local municipality.

This registry-based study included only deceased patients and all the data used in the analysis had been obtained as a part of routine clinical assessments. No patient interventions were performed. The study was executed with the permission of the authorities of TUH and permission for data collection was requested from Turku Clinical Research Centre, Turku CRC (Research number T94/2017 and research permission number T06/011/17). According to the Finnish law, the legislation does not mandate any Ethics Committee approval for retrospective registry-based studies.

Statistical analysis

Patient characteristics were compared between PC group and SC group using Fisher’s exact test (categorical variables like gender) or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) when continuous variables followed normal distribution and Wilcoxon rank sum test otherwise. The interventions and amount of interventions were compared between PC-group and SC-group using the same methods.

All statistical tests were performed as 2-sided, with a significance level set at 0.05. The analyses were performed using SAS software, version 9.4 for Windows (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

A total of 378 pancreatic cancer patients were eligible for the analysis. 110 patients (29%) had a histological verification of pancreatic cancer. The median overall survival was 2.6 months from the diagnosis with a range from 0.1 months to 51.8 months. Patient characteristics including PAD verification, overall survival, chemotherapies and radiotherapies given are shown in .

Table 1. Patient characteristics for pancreatic cancer patients with a contact to the tertiary care during the last 30 days of life.

All patients received standard oncological and surgical care. 76 patients (20%, mean age 71) were referred to the palliative care unit (PC group). Consequently, 302 patients (74%, mean age 71) received standard care with no palliative intervention (SC group). Both groups received similar oncological treatments in terms of the use of chemotherapy and radiotherapy. The patients in PC group had a longer overall survival (median 5.4 months vs. 1.9 months, p < 0.0001). Distribution of PAD-verifications did not differ between the groups ().

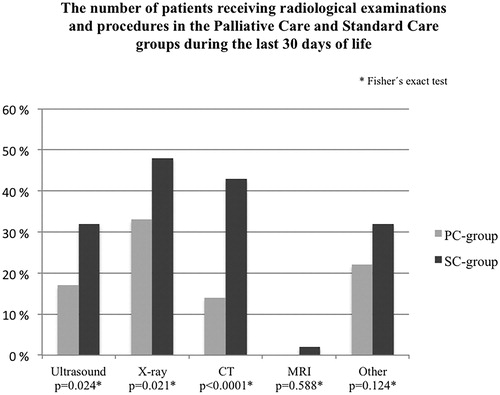

The patients in the PC group had less radiological examinations (p < 0.0001), hospitalisations in the university hospital (p < 0.0001) and emergency department visits (p = 0.021) during the last month of life (). They did not die in TUH as often as the patients in SC group (8 vs. 21%, p = 0.011). Also, the medical costs in tertiary care were significantly lower for the patients in the PC group (p < 0.0001). Mean cost varied from 2049 euros in the PC group to 4574 euros in the SC group and median cost from 591 euros in PC group to 3268 euros in SC group (range 1–21.484 euros vs. 1.5–43 603 euros) ().

Figure 1. Number of patients receiving radiological examinations and procedures in the palliative care and standard care groups during the last 30 days of life.

Table 2. The amount of interventions for patients with pancreatic cancer in the university hospital during the last 30 days of life.

Of the 76 patients who had a contact to the palliative care unit, 32% (n = 26) had one contact, 20% two contacts (n = 16) and 48% (n = 39) more than two contacts. The median time from the first visit to the palliative care unit to death was 62 days (range 0–1070 days, mean 114 days). Twenty-five patients had the first contact to the palliative care unit during the last month and of these patients 6 patients during the last week of life. For patients receiving late palliative consultation during the last 30 days of life (n = 25), the median OS was significantly shorter (2.90 months, range 0.4–17.8 months) when compared to patients visiting palliative care unit earlier (6.98 months, range 0.33-39.53 months, p < 0.0001).

Discussion

Pancreatic cancer patients in the PC group had less radiological examinations, hospitalisations in the university hospital and emergency department visits during the last month of life compared to the SC group with no contact to the palliative care unit. The number of patients dying in the university hospital was threefold in the SC group. In addition, medical costs in the tertiary care during the last month of life were significantly lower for the patients in the PC group.

The present study based on real world data establishes the importance of palliative intervention as a part of treatment for patients with pancreatic cancer. In the SC group treatment without palliative intervention during the last month of life may have caused unnecessary costs without any obvious additional benefits for the patients. The local treatment strategies have been revised and systematic palliative intervention is now offered for all newly diagnosed pancreatic cancer patients in TUH.

The median overall survival varied between the studied groups (1.9 vs. 5.4 months in the SC and PC groups, respectively) even though the activity of oncological treatments was similar. This might suggest that patients with more aggressive disease were not referred to the palliative care unit or because the palliative intervention was typically offered only after finishing active oncological treatments, patients with more aggressive or advanced cancer did not have time to reach specialised palliative care. According to this finding, early integrated palliative care and collaboration between specialities should be warranted also for patients with the most aggressive disease.

The health care costs during the last month of life varied dramatically between the PC and SC groups in tertiary care, because patients who were not referred to a palliative care unit visited university hospital more frequently. Providing a possibility for palliative intervention may therefore provide a place to decrease costs of end-of-life care without compromising the quality of life [Citation12]. Unfortunately, we could not include primary care costs in the present analysis. According to the literature comparing the end of life treatment of patients with pancreatic cancer in acute care hospital and in the inpatient palliative care unit, the patients in the inpatient palliative care units have, however, been found to have lower medical costs [Citation14].

In our analysis, palliative care intervention decreased the number of visits to emergency department and need for radiological examinations reflecting the fact that advanced care planning enables adequate symptom control for these patients near home. The most common reasons for emergency department visits are inability to cope at home, definitive surgical problem [Citation15] and abdominal pain [Citation16], and due to a high burden of symptoms, pancreatic cancer patients are often in the need for health care services near end of life. Even though ED visits may be very distressing to the patients, not all of them are avoidable, and may still be very well justified [Citation17]. In TUH district surgical problems, such as biliary tract stenting can only be done in tertiary care.

In the present study, the number of patients who died in tertiary care was threefold in the SC group when compared to the PC group (21 vs. 8%, respectively). This might indicate that by increasing the availability of palliative intervention the number of patients dying in tertiary care could be decreased. This may have very important effects, because patients who have died in an intensive care unit or a hospital have been reported to experience more physical and emotional distress and to have worse quality of life compared to those who die at home [Citation18].

In addition to palliative procedures, the use of oncological treatments needs to be assessed when evaluating the end-of-life care. The use of chemotherapy near end of life has been reported to be associated with increased hospital admissions, emergency department visits, death in a hospital and fewer days in hospice care in patients with stage IV pancreatic cancer [Citation19]. In the present study, the use of chemotherapy was in line with the recommendations by Earle et al. [Citation20] and less frequent than in our own earlier series of all cancer patients [Citation21] and in a Canadian cohort of advanced pancreatic cancer patients [Citation10], as only 3% of the patients received chemotherapy during the last 30 days of life. Radiotherapy is available in TUH also near end of life [Citation22], but in the present study, only 1% of the patients received radiotherapy during the last month of life.

The present study should also be interpreted in the context of its limitations. Comprehensive data are available from the electronic patient records but there are also some restrictions as typical in retrospective studies. For example, data on symptom burden, the quality of life, physical performance status and experiences of caregivers could not be assessed. These data could have provided a better overview of the groups and maybe explain some differences regarding interventions, hospitalisations, visit to emergency department and survival time, for instance. Prospective study design has been built up to include these in an upcoming study. The patients were selected from the database by using the ICD-10 codes, but data was manually validated afterwards in terms of diagnose, PAD verification and type of palliative intervention. The analysis could not include, however, patients who did not have any contact to the TUH. The analysis on the cost of care in the university hospital does not include year 2011 or the costs of care in primary care. However, TUH is the only place in the area where computer tomography imaging and biliary tract stenting is available, and it is obvious that patients were not referred to computer tomography studies outside TUH. The cause of death was not verified and some of the patients may have died for other reasons, e.g., because of the complications of treatment.

Conclusion

There was an association between palliative care intervention and decrease in the number of radiological examinations, emergency department visits and days on a ward of the university hospital during the last month of life for patients with pancreatic cancer. Lower costs in tertiary care hospital were also observed for patients who had a contact to the palliative care unit. These results support the guidelines that palliative care intervention should be an essential part of the treatment for all pancreatic cancer patients.

Ethical approval

This registry-based study included only deceased patients and all the data used in the analysis had been obtained as a part of routine clinical assessments. No patient interventions were performed. The study was executed with the permission of the authorities of TUH, and according to the Finnish law, the legislation does not mandate any Ethics Committee approval.

Author contributions

LR, OH and SJ have planned the study design. LR has validated the data. EL has done the statistical analysis. LR was the major contributor in writing the manuscript. All authors have contributed in writing the manuscript and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Auria Clinical Informatics and Juha Varjonen for the collaboration and providing the data for the analysis, and Sari Kämppi for the language revision.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interests.

Data availability statement

The datasets (clinical data based on patient records) analysed during the current study are not publicly available according to Finnish law.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ducreux M, Cuhna AS, Caramella C, et al. Cancer of the pancreas: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2015;26(Suppl 5):56–68.

- Danckert B, Ferlay J, Engholm G, et al. NORDCAN: Cancer Incidence, Mortality, Prevalence and Survival in the Nordic Countries, Version 8.2 (26.03.2019). Association of the Nordic Cancer Registries. Danish Cancer Society., Available from http://www.ancr.nu (2019, accessed 11/19).

- Finnish Cancer Registry. Cancer Statistics, Cancer 2017 Report, Available from https://cancerregistry.fi/statistics/cancer-statistics/ (2019, accessed 9/12).

- Mayo SC, Nathan H, Cameron JL, et al. Conditional survival in patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma resected with curative intent. Cancer. 2012;118(10):2674–2681.

- Ferrell BR, Temel JS, Temin S, et al. Integration of Palliative Care Into Standard Oncology Care: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline Update. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(1):96–112.

- Sohal DPS, Kennedy EB, Khorana A, et al. Metastatic pancreatic cancer: ASCO clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(24):2545–2556.

- Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(8):733–742.

- Greer JA, Pirl WF, Jackson VA, et al. Effect of early palliative care on chemotherapy use and end-of-life care in patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(4):394–400.

- Otsuka M, Koyama A, Matsuoka H, et al. Early palliative intervention for patients with advanced cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2013;43(8):788–794.

- Jang RW, Krzyzanowska MK, Zimmermann C, et al. Palliative care and the aggressiveness of end-of-life care in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107(3):dju424.

- Zimmermann C, Swami N, Krzyzanowska M, et al. Early palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2014;383(9930):1721–1730.

- Kavalieratos D, Corbelli J, Zhang D, et al. Association between palliative care and patient and caregiver outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2016;316(20):2104–2114.

- Nordly M, Skov Benthien K, Vadstrup ES, et al. Systematic fast-track transition from oncological treatment to dyadic specialized palliative home care: DOMUS – a randomized clinical trial. Palliat Med. 2019;33(2):135–149.

- Wang JP, Wu CY, Hwang IH, et al. How different is the care of terminal pancreatic cancer patients in inpatient palliative care units and acute hospital wards? A nationwide population-based study. BMC Palliat Care. 2016;15(1):1.

- Hirvonen OM, Alalahti JE, Syrjanen KJ, et al. End-of-life decisions guiding the palliative care of cancer patients visiting emergency department in South Western Finland: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Palliat Care. 2018;17(1):17.

- Barbera L, Taylor C, Dudgeon D. Why do patients with cancer visit the emergency department near the end of life? CMAJ. 2010;182(6):563–568.

- Delgado-Guay MO, Kim YJ, Shin SH, et al. Avoidable and unavoidable visits to the emergency department among patients with advanced cancer receiving outpatient palliative care. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2015;49(3):497–504.

- Wright AA, Keating NL, Balboni TA, et al. Place of death: correlations with quality of life of patients with cancer and predictors of bereaved caregivers' mental health. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(29):4457–4464.

- Bao Y, Maciejewski RC, Garrido MM, et al. Chemotherapy use, end-of-life care, and costs of care among patients diagnosed with stage IV pancreatic cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;55(4):1113–1121.

- Earle CC, Neville BA, Landrum MB, et al. Evaluating claims-based indicators of the intensity of end-of-life cancer care. Int J Qual Health Care. 2005;17(6):505–509.

- Rautakorpi L K, Seyednasrollah F, Mäkelä J M, et al. End-of-life chemotherapy use at a Finnish university hospital: a retrospective cohort study. Acta Oncologica. 2017;56(10):1272–1276.

- Rautakorpi LK, Makela JM, Seyednasrollah F, et al. Assessing the utilization of radiotherapy near end of life at a Finnish University Hospital: a retrospective cohort study. Acta Oncol. 2017;56(10):1265–1271.