Abstract

Background

Survival rates for breast cancer (BC) are increasing, leading to growing interest in treatment-related late-effects. The aim of the present study was to explore late effects using Patient-Reported Outcome Measures in postmenopausal BC survivors in standard follow-up care. The results were compared to age- and gender-matched data from the general Danish population.

Material and methods

Postmenopausal BC survivors in routine follow-up care between April 2016 and February 2018 at the Department of Oncology, Aarhus University Hospital, Denmark were asked to complete the EORTC QLQ-C30 and BR23 questionnaires together with three items on neuropathy, myalgia, and arthralgia from the PRO-CTCAE. Patients were at different time intervals from primary treatment, enabling a cross-sectional study of reported late effects at different time points after primary treatment. The time intervals used in the analysis were year ≤1, 1–2, 2–3, 3–4, 4–5 and 5+. The QLQ-C30 results were compared with reference data from the general Danish female population. Between-group differences are presented as effect sizes (ESs) (Cohen’s d).

Results

A total of 1089 BC survivors participated. Compared with the reference group, BC survivors reported better global health status 2–3 and 4–5 years after surgery (d = 0.26) and physical functioning 2–3 years after (0.21). Poorer outcomes in BC survivors compared with the reference group were found for cognitive functioning (0–4 and 5+ years), fatigue (0–2 years), insomnia (1–3 years), emotional functioning (3–4 years), and social functioning (≤1 year after surgery) with ESs ranging from 0.20 to 0.41. For the remaining outcomes, no ESs exceeded 0.20.

Conclusion

Only small to medium ESs were found for better global health and physical functioning and poorer outcomes for cognitive functioning, fatigue, insomnia, emotional functioning, and social functioning in postmenopausal BC survivors, who otherwise reported similar overall health-related quality of life compared with the general Danish female population.

Introduction

Breast cancer (BC) is the most common (non-skin) cancer, accounting for 1 in 4 cancers in women, and the number of BC survivors is increasing [Citation1], with five-year survival around 89% [Citation2]. However, the improved survival is often obtained at a cost, with more intense treatments resulting in persistent symptoms and late effects. There is an increased interest in how these late effects influence the longer-term health-related quality of life (HRQoL). Compared to premenopausal patients, postmenopausal BC survivors comprise an older and ageing population, and HRQoL is generally assumed to deteriorate with age, with at least some studies reporting declining HRQoL from the late sixties [Citation3,Citation4]. It is often unclear to what extent symptoms and impaired HRQoL in this patient group stem from late effects after BC treatment, from general aging, or a combination of both. It is therefore clinically relevant to examine the symptoms and functional impairments of postmenopausal BC survivors and compare the prevalence and severity of these with the symptoms and impairments experienced by women of similar age in the general population.

Despite overall high HRQoL among many BC survivors, a wide range of symptoms have been described up to several years after primary diagnosis [Citation5]. Among the common surgery and radiotherapy-related loco-regional late effects are lymphedema, impaired shoulder functioning, and breast fibrosis [Citation6–8]. Late effects after systemic treatments include chemotherapy-induced neuropathies, aromatase inhibitor-associated myalgia and arthralgia, fatigue, and pain [Citation9–12]. Other commonly reported BC-related late effects are cognitive difficulties, impaired body image, and sexual dysfunction [Citation13,Citation14].

When collecting systematic data on late effects, Patient Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs) are core tools [Citation15,Citation16]. So far, relatively few studies have compared results of PROMs completed by BC survivors with the results found in reference populations. Using the EORTC QLQ-C30 global health status subscale, the results for BC survivors and reference groups were generally comparable in most studies [Citation17–19]. In contrast, regarding the more specific subscales, BC survivors reported higher levels of symptoms, e.g., fatigue and dyspnea, as well as larger deficits in role, emotional, social and cognitive functioning [Citation17–21]. Other studies used the 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36) questionnaire [Citation22] and likewise found impairment in HRQoL in BC survivors compared to the reference populations [Citation23–26]. It should be noted in one study, differences where moderated by time since diagnosis with the largest differences closest to diagnosis [Citation24], and in two other studies differences between BC survivors and control groups were only found one year post-diagnosis with follow-up periods of respectively two years and ten years [Citation25,Citation26].

Conflicting results have been published in two studies focusing specifically on postmenopausal BC survivors. In a Swedish study, the SF-36 scores of 150 postmenopausal BC survivors were compared with data from a reference population revealing better HRQoL in BC survivors as indicated by higher scores in general health and all investigated domains [Citation27]. A large US study of 3083 postmenopausal BC survivors found scores on the 12-item Short-Form Version (SF-12) physical and mental component scales to be similar to scores from non-cancer populations [Citation28,Citation29]. While these results could suggest that the overall HRQoL in postmenopausal BC survivors is similar to that of non-cancer populations, an important limitation is that the results of the HRQoL measures of SF-36 and SF-12 are not directly comparable to the results of the QLQ-C30, which includes additional symptoms and domains not found in the SF-36 or SF-12, e.g., self-reported cognitive impairment.

Taken together, from the available data, it is still unclear how the symptoms and functioning of postmenopausal BC survivors as assessed with the QLQ-C30 compare to those of an age and gender matched reference population. The present study adds to existing literature by examining QLQ-C30 data of 1089 postmenopausal BC survivors followed for more than 5 years and comparing the results with the scores of a Danish reference group.

Material and methods

Design and study population

Since April 2016, all BC survivors receiving routine follow-up care at the Department of Oncology, Aarhus University Hospital, have been asked to complete a patient-reported outcome (PRO) questionnaire before each planned visit, irrespective of the time since their diagnosis and treatment. The aim was to provide better knowledge about symptoms experienced by patients in the follow-up program prior to the consultation with the oncologist.

A link and instructions on how to access the Ambuflex online questionnaire was e-mailed to the patients. In the present study we used only the first questionnaire filled out by patients between April 2016 and February 2018, enabling a cross-sectional analysis of patients at different time intervals from their primary breast cancer treatment. Furthermore, in the present study, we only analyzed postmenopausal early BC patients treated according to guidelines of the Danish Breast Cancer Group (DBCG). Exclusion criteria were premenopausal status, secondary cancer, loco-regional or distant recurrent disease, and not treated according to DBCG guidelines.

Questionnaire and registry data

The PRO questionnaire and additional items were chosen in accordance with the recommendations of the Danish National Board of Health regarding symptoms to be evaluated during follow-up of early stage breast cancer. Depending on the primary BC treatment received (endocrine therapy (ET) only, chemotherapy (CT) only, or CT + ET), the questionnaire was completed on minimum one of the following planned visits after primary treatment: 3 weeks, 3 months, 6 months, 12 months, and at 12-month intervals thereafter.

Low risk patients (age 60 years or older, ER positive, HER2-negative, lymph node negative, and tumor ≤ 10 mm) did not receive any adjuvant systemic therapy and were not followed at the oncological department, but had a 12 month visit at their surgical department, and did not complete the questionnaire.

The questionnaire included the full EORTC QLQ-C30 [Citation30] and QLQ-BR23 questionnaires [Citation31] supplemented with three items on neuropathy, myalgia, and arthralgia from the PRO-CTCAE-system [Citation32]. The QLQ-C30 provides scores on global health status, five functional subscales (physical, role, emotional, cognitive, and social) and nine symptom scales (fatigue, nausea and vomiting, pain, dyspnea, insomnia, appetite loss, constipation, diarrhea and financial difficulties). The QLQ-BR23 consists of four functional subscales (body image, sexual functioning, sexual enjoyment, and future perspective) and four symptom scales (systemic therapy side effects, breast symptoms, arm symptoms, and upset by hair loss).

Questionnaire data was retrieved from the Ambuflex database. To examine associations of symptoms and late effects with the adjuvant treatment, data on patient characteristics and specific treatments were retrieved from the DBCG database and medical records. Data were stored in accordance with current requirements of the Danish Data Protection Agency.

Statistical analyses

Surgery was categorized as either lumpectomy or mastectomy. Axillary surgery was categorized as sentinel node biopsy or axillary lymph node dissection (ALND). Before 2009 some patients had a partial axillary dissection. Radiotherapy (RT) was categorized as given after lumpectomy vs. mastectomy and local vs. locoregional. Chemotherapy, HER2-targeted treatment and endocrine treatment were categorized as given or not. For a detailed description of treatment modalities see Supplementary materials.

The time of the first questionnaire was grouped in yearly intervals: ≤1, 1–2, 2–3, 3–4, 4–5 and 5+ years after surgery. Differences in patient characteristics between yearly intervals were tested with chi-squared tests.

First, data from the QLQ-C30 and QLQ-BR23 underwent a linear transformation according to the EORTC scoring manual and were presented as functional domain and symptom scores ranging from 0–100, with higher scores on functional domains and lower scores on symptom scales representing higher HRQoL [Citation33]. Although the method of linear transformation has not been validated for PRO-CTCAE data, for the purpose of comparability, the PRO-CTCAE data also underwent the same linear transformation. Results were grouped in yearly intervals to visualize possible indications of time-dependent changes. One-way analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were used to test for statistically significant differences in scores between yearly intervals.

Second, the QLQ-C30 results were compared with reference data from the general Danish population [Citation34], where randomly selected persons (n = 1832) drawn from the Danish Civil Registration System were asked to complete the EORTC QLQ-C30, and data were presented at 10-year age groups for each gender. Reference data for each postsurgical time interval were calculated based on the age distribution of the patients at that time interval. Thus, reference data for the ≤1 year after surgery group reflects data from younger women compared to e.g. reference data for the 5+ years after surgery group. Between-group differences are presented as effect sizes (ESs) (Cohen’s d), with values of 0.2, 0.5, and 0.8 considered small, medium, and large, respectively [Citation35]. Statistical differences were tested with one-sample t-tests. To adjust for multiple comparisons, Holm’s test was applied [Citation36]. Previously established Minimally Important Differences (MIDs) for the EORTC QLQ-C30 were used when interpreting the clinical relevance of the findings [Citation37].

Third, for domains showing clinical relevant differences between BC survivors and the reference population, explorative univariate subgroup analyses were performed for age, type of surgery, ALND, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy. Differences between BC patients and the reference population were presented with ESs.

Statistical analyses were conducted with IBM SPSS Statistics Version 20.0 and Stata 16.0 (StataCorp, Texas, USA).

Ethics

The study was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency and by the Danish Patient Safety Authority.

Results

Initially, the cohort included 1788 postmenopausal patients in the follow-up program between April 2016 and February 2018. After excluding 167 patients with secondary cancer, loco-regional or distant recurrent disease, or not treated according to DBCG guidelines, and 532 patients, who never completed a questionnaire, a total of 1089 patients were eligible for analysis (Supplementary Figure S1). Non-responders were older (mean age 68 vs. 64 years), more often mastectomised (38% vs. 31%), had often 10+ positive lymph nodes (9% vs. 3%), less often treated with radiotherapy (no RT 25% vs. 16%), less treated with chemotherapy (no CT 70% vs. 57%), and less treated with endocrine treatment (89% vs. 93%). Non-responder analyses are shown in Supplementary Table S1. The number of missing items in each subscale was generally limited to 1–3%. The exceptions were sexual functioning and sexual enjoyment, which had 6% and 12% missing items respectively. Missingness for these items was unrelated to age.

The mean age was 64 years (range 37–88). The largest number of patients, n = 318 (29%), were found in the first year after surgery, explained by the more intensified follow-up schedule. One hundred and twenty-seven patients (11.6%) were followed more than 5 years after surgery. Of these, 44 patients had prolonged follow-up due to participation in clinical trials. Termination of endocrine treatment in the beginning of the sixth year after surgery was common, while some had prolonged follow-up for individual clinical reasons e.g., patient preference. Tumor and treatment characteristics are shown in .

Table 1. Patient and treatment characteristics.

Questionnaire results

As shown in , statistically significant differences between yearly intervals were found for global health status, fatigue, future perspective, and breast symptoms. Global health status scores ranged between 71.6 (≤1 year after surgery) to 79.6 (2–3 years after surgery). Fatigue scores were highest ≤1 year after surgery (30.6) and lowest (21.2) 5 or more years after surgery. Future perspective scores were lowest (63.4) ≤1 years after surgery and highest (71.9) 4–5 years after surgery, and the highest breast symptom scores (21.8) were observed ≤1 year after surgery while the lowest (11.0) were found 4–5 years after surgery. No differences between time of assessment were found for the remaining functional domains and symptoms.

Table 2. Trend over time for QLQ-C30, QLQ-BR23 and CTCAE scores.

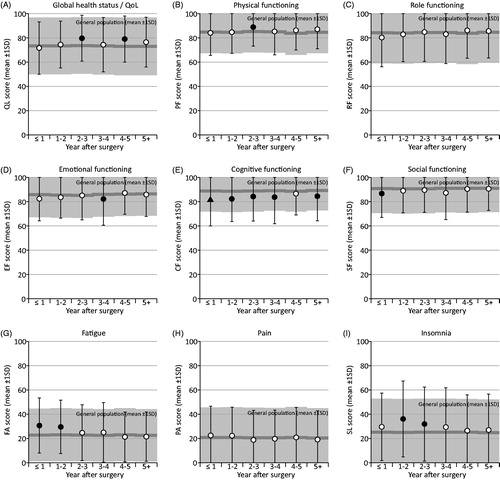

Comparative analysis

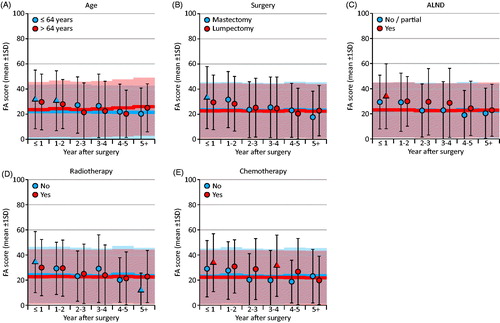

BC survivors reported better Global Health Status at 2–3 and 4–5 years after surgery and physical functioning at 3–4 years compared with the reference group. Poorer outcomes in BC survivors compared with the reference group were found for cognitive functioning (0–4, and 5+ years), fatigue (0–2 years), insomnia (1–3 years), emotional functioning (3–4 years), and social functioning (≤1 year after surgery). The between-group differences are shown in with effect sizes. All statistically significant differences corresponded to effect sizes ranging between small (0.2) and medium (0.5). For the remaining functional domains and symptom scales, no differences exceeded an effect size of d = 0.2. (For exact effect sizes and p-values, see Supplementary Table S2). Differences between BC survivors and the reference group exceeding MIDs were only found for cognitive functioning at year 0–4 and 5+ after surgery with poorer outcomes in BC survivors compared to the reference group.

Figure 1. Changes in QLQ-C30 scores over time after surgery and compared to the Danish general population. The normative data of the reference group were adjusted for different age distributions at each time interval. Absolute effect sizes: white circle: <0.2; black circle: 0.2–0.4; black triangle: >0.4.

Explorative analysis

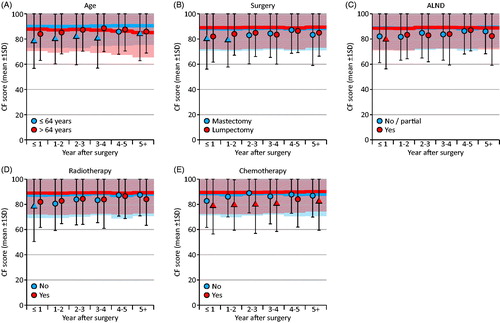

When further exploring the scores with the largest differences from the reference group, patients under 65 years of age had lower cognitive functioning compared to the reference population, with the ES (d) being larger than 0.4 at year 0–4 and 5+ after surgery. As seen in , this was in contrast to older patients (≥65), who reported similar cognitive functioning as the reference population. Patients who had received chemotherapy reported lower cognitive functioning than the reference population (ES (d) >0.4 at year 0–4 and 5+ after surgery) in contrast to patients who had not received chemotherapy who reported similar cognitive functioning as the reference population. ALND, type of surgery, and radiotherapy was not associated with self-reported cognitive functioning.

Figure 2. Subgroup analysis of cognitive functioning. The normative data of the reference group were adjusted for different age distributions at each time interval. Absolute effect sizes: circle: <0.4; triangle: >0.4.

As shown in , patients who had received chemotherapy felt more fatigued than the reference population, with an ES (d) >0.4 found at year ≤1 and 3–4 after surgery. Patients who had not received chemotherapy reported similar levels of fatigue as the reference population. Age, ALND, type of surgery, and radiotherapy was not associated with fatigue.

Discussion

Using a cross-sectional approach, we analyzed PRO data from a cohort of 1089 postmenopausal BC survivors who at different time points after early breast cancer treatment had completed the EORTC QLQ-C30 and other items. When comparing the QLQ-C30 scores of postmenopausal BC survivors with the scores found in a reference sample of Danish women from the general population, BC survivors reported better Global Heath Status and physical functioning, poorer cognitive and emotional functioning, and higher levels of fatigue and insomnia. The differences were generally small, and clinically significant differences exceeding the MID were only found for cognitive function. No differences between BC survivors and women in the general population were found for the remaining subscales.

Our results generally support previous findings of comparable overall HRQoL in BC survivors and reference populations, although a more uneven picture emerges when examining scores on functional domain and symptom scales. Most studies, using the EORTC QLQ-C30, have found statistically significant deficits in multiple functioning domains [Citation17–21], and symptom scales [Citation18–21] among BC survivors. In line with these studies we found poorer cognitive functioning among BC survivors throughout the follow-up period and higher level of fatigue and insomnia, respectively 0–2 years and 1–3 years after surgery, compared to the reference group. Subject to the cross-sectional design of our study, the latter results for fatigue and insomnia could suggest some deficits in HRQoL in BC survivors are reduced over time, also described in three previous studies using the SF-36 [Citation24–26]. In contrast to existing literature and our results, one study investigating specifically postmenopausal BC survivors with the SF-36 found better HRQoL on multiple subscales among postmenopausal BC survivors compared with a reference sample [Citation27].

As even small, clinically non-significant differences may become statistically significant in large samples, it is relevant to evaluate the differences found between BC survivors and reference groups in terms of their magnitude, i.e., their effect sizes, and their relevance. Using a recently proposed MID for the QLQ-C30 [Citation37], only self-reported cognitive functioning appeared to be clearly impaired in BC survivors when compared with the general population of women in the same age groups. Further examination of the findings showed that self-reported impairment of cognitive function in BC survivors was associated not only with older age, which could be expected, but also with having received chemotherapy. Similar results were reported in a sample of 441 BC survivors two years after diagnosis with women who had received adjuvant chemotherapy reporting impaired cognitive function on the QLQ-C30 compared with women who had not received chemotherapy [Citation38]. However, in 1889 recurrence-free survivors from a national cohort of women treated for primary BC, no differences in self-reported cognitive function were found at 7–9 years after diagnosis between those who had received systemic therapies and those who had not [Citation39]. The results could be interpreted as suggesting that the relative impact of having received chemotherapy is reduced over time. It should, however, be noted that while the QLQ-C30 assesses cognitive impairment with only two items, the latter study of long-term self-reported cognitive impairment used the 25-item, three-subscale Cognitive Failures Questionnaire [Citation40,Citation41], and the comparability of the two instruments is not known.

Better global health was found in postmenopausal BC survivors at 2–3 and 4–5 years after surgery compared to the reference group, a result not described in existing literature, except for one study [Citation27]. Previous research suggest such findings may not necessarily reflect a true difference in QoL, but could be due to response shift, also labeled the ‘well-being paradox’, which suggests that patients may alter the way they understand and answer, e.g., HRQoL questionnaires, because of recalibration, reprioritizing, and reconceptualizing in the light of their cancer diagnosis and treatment experience [Citation42].

Additional findings worth noting include the higher levels of fatigue in the first year and 3–4 years after surgery found in women having received chemotherapy. This result is supported by previous findings, e.g., of a cohort study of 1957 BC survivors which found overall fatigue comparable to that reported by a matched general population sample, but also found more severe fatigue in a subgroup of women who had received chemotherapy [Citation43]. Furthermore, our data suggested strikingly low levels of sexual function in BC survivors. This is in contrast to the results of other studies using the same PRO measures. E.g., in a Dutch study of 175 women following breast-conserving therapy for BC [Citation44], sexual functioning scores assessed with the QLQ-BR23 ranged between 72.8 and 79.6, compared with 16.6 to 19.5 in our sample. On the other hand, an Australian study found self-reported sexual function problems in 70% of a BC survivor population (n = 1011), and postmenopausal status was a significant predictor thereof. Our data suggest that impaired sexual function may be an under-recognized problem in postmenopausal BC survivors warranting further research, including comparisons with appropriate reference groups.

Taken together, with the exception of self-reported cognitive function, our results suggest that on average, the overall HRQoL of BC survivors seems comparable to the that of women of similar age in the general population. However, this does not rule out the possibility that a smaller group of BC survivors may experience severe functional impairment or high levels of symptoms, while others may even experience higher levels of QoL due to adjustments in life style after the cancer experience. It could therefore be appropriate to move beyond investigating mean scores and identify how symptoms and late effects may develop and change over time in subgroups of patients and survivors. A recent study measuring responses to the QLQ-C30 in 250 BC patients over a 1-year period after completion of radiotherapy thus found three distinct types of clusters of trajectories for all outcome variables, i.e., stable trajectories of high, medium, and low HRQoL [Citation45], suggesting that identifying the predictors of the trajectories could identify those with special rehabilitation needs.

A primary strength of our study is that the results were obtained from a relatively large unselected group of postmenopausal BC survivors asked to provide data to be used in subsequent consultations. We believe that this increases the external validity of our findings and provide data to be used in the clinical setting when discussing pros and cons of adjuvant treatment with the patients. Based on our clinical experience, the use of PROs have made consultations more patient-centered as they highlight self-reported symptoms. An important limitation which applies to many studies in the field is that we do not have baseline data recorded prior to adjuvant therapy. Such data are relevant when assessing the possible role of adjuvant therapy in the development of late effects. A second limitation could be that HRQoL measures such as the QLQ-C30 may not sufficiently cover the symptoms and late effects experienced by many cancer survivors, e.g., fear of cancer recurrence [Citation46] and persistent pain [Citation12]. A third limitation, non-responders were a large group of patients (n = 532) and differed by older age and less adjuvant treatment. We believe this finding reflects one of the costs of conducting online questionnaires in the real-life clinical setting, and highlights an unmet need for a specialized focus on older people filling out PRO questionnaires.

On average, postmenopausal BC survivors reported similar scores on the QLQ-C30 compared with the same age groups in the general Danish female population. Small-to-medium differences were found for better global health status and physical functioning, poorer cognitive and emotional functioning, and higher levels of fatigue and insomnia among BC survivors. Additional data from the QLQ-BR23 indicated low levels of sexual function. Future research is recommended to use trajectory analyses to identify BC survivors with special rehabilitation needs.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (123.9 KB)Disclosure statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, et al. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6):394–424.

- Rojas K, Stuckey A. Breast cancer epidemiology and risk factors. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2016;59(4):651–672.

- Netuveli G, Wiggins RD, Hildon Z, et al. Quality of life at older ages: evidence from the English longitudinal study of aging (wave 1). J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60(4):357–363.

- Layte R, Sexton E, Savva G. Quality of life in older age: evidence from an Irish cohort study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61:S299–S305.

- Ganz PA, Desmond KA, Leedham B, et al. Quality of life in long-term, disease-free survivors of breast cancer: a follow-up study. CancerSpectrum Knowl Environ. 2002;94(1):39–49.

- DiSipio T, Rye S, Newman B, et al. Incidence of unilateral arm lymphoedema after breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(6):500–515.

- Levangie PK, Drouin J. Magnitude of late effects of breast cancer treatments on shoulder function: a systematic review. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;116(1):1–15.

- Bartelink H, Maingon P, Poortmans P, et al. Whole-breast irradiation with or without a boost for patients treated with breast-conserving surgery for early breast cancer: 20-year follow-up of a randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(1):47–56.

- Bao T, Basal C, Seluzicki C, et al. Long-term chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy among breast cancer survivors: prevalence, risk factors, and fall risk. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2016;159(2):327–333.

- Hong D, Bi L, Zhou J, et al. Incidence of menopausal symptoms in postmenopausal breast cancer patients treated with aromatase inhibitors. Oncotarget. 2017;8(25):40558–40567.

- Bardwell WA, Profant J, Casden DR, for the Women's Healthy Eating & Living (WHEL) Study Group, et al. The relative importance of specific risk factors for insomnia in women treated for early-stage breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2008;17(1):9–18.

- Johannsen M, Christensen S, Zachariae R, et al. Socio-demographic, treatment-related, and health behavioral predictors of persistent pain 15 months and 7-9 years after surgery: a nationwide prospective study of women treated for primary breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2015;152(3):645–658.

- Carreira H, Williams R, Müller M, et al. Associations between breast cancer survivorship and adverse mental health outcomes: a systematic review. JNCI J Natl Cancer Inst. 2018;110(12):1311–1327.

- Lyngholm CD, Christiansen PM, Damsgaard TE, et al. Long-term follow-up of late morbidity, cosmetic outcome and body image after breast conserving therapy. A study from the Danish Breast Cancer Cooperative Group (DBCG). Acta Oncol. 2013;52(2):259–269.

- Lagendijk M, van Egdom LSE, Richel C, et al. Patient reported outcome measures in breast cancer patients. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2018;44(7):963–968.

- Brouwers PJAM, van Loon J, Houben RMA, et al. Are PROMs sufficient to record late outcome of breast cancer patients treated with radiotherapy? A comparison between patient and clinician reported outcome through an outpatient clinic after 10years of follow up. Radiother Oncol. 2018;126(1):163–169.

- Hsu T, Ennis M, Hood N, et al. Quality of life in long-term breast cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(28):3540–3548.

- de Ligt KM, Heins M, Verloop J, et al. The impact of health symptoms on health-related quality of life in early-stage breast cancer survivors. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2019;178(3):703–711.

- Koch L, Jansen L, Herrmann A, et al. Quality of life in long-term breast cancer survivors – a 10-year longitudinal population-based study. Acta Oncol Stockh Swed. 2013;52(6):1119–1128.

- Götze H, Taubenheim S, Dietz A, et al. Comorbid conditions and health-related quality of life in long-term cancer survivors-associations with demographic and medical characteristics. J Cancer Surviv. 2018;12(5):712–720.

- Klein D, Mercier M, Abeilard E, et al. Long-term quality of life after breast cancer: a French registry-based controlled study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;129(1):125–134.

- Ware JE, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30(6):473–483.

- Kroenke CH, Rosner B, Chen WY, et al. Functional impact of breast cancer by age at diagnosis. J Cin Oncol. 2004;22(10):1849–1856.

- Karlsen RV, Frederiksen K, Larsen MB, et al. The impact of a breast cancer diagnosis on health-related quality of life. A prospective comparison among middle-aged to elderly women with and without breast cancer. Acta Oncol. 2016;55(6):720–727.

- Stover AM, Mayer DK, Muss H, et al. Quality of life changes during the pre- to postdiagnosis period and treatment-related recovery time in older women with breast cancer. Cancer. 2014;120(12):1881–1889.

- Avis NE, Levine B, Goyal N, et al. Health-related quality of life among breast cancer survivors and noncancer controls over 10 years: Pink SWAN . Cancer. 2020;126(10):2296–2304.

- Browall M, Östlund U, Henoch I, et al. The course of Health Related Quality of Life in postmenopausal women with breast cancer from breast surgery and up to five years post-treatment. The Breast. 2013;22(5):952–957.

- Ware J, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34(3):220–233.

- Neuner JM, Zokoe N, McGinley EL, et al. Quality of life among a population-based cohort of older patients with breast cancer. Breast. 2014;23(5):609–616.

- Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85(5):365–376.

- Sprangers MA, Groenvold M, Arraras JI, et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer breast cancer-specific quality-of-life questionnaire module: first results from a three-country field study. J Clin Oncol off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 1996;14(10):2756–2768.

- Basch E, Reeve BB, Mitchell SA, et al. Development of the National Cancer Institute’s patient-reported outcomes version of the common terminology criteria for adverse events (PRO-CTCAE). J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106(9):dju244.

- Fayers PM, Aaronson N, Bjordal K, et al. EORTC QLQ-C30 scoring manual. 3rd ed. Brussels: European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer; 2001.

- Juul T, Petersen MA, Holzner B, et al. Danish population-based reference data for the EORTC QLQ-C30: associations with gender, age and morbidity. Qual Life Res. 2014;23(8):2183–2193.

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988.

- Aickin M, Gensler H. Adjusting for multiple testing when reporting research results: the Bonferroni vs Holm methods. AM J Public Health. 1996;86(5):726–728.

- Musoro JZ, Coens C, Fiteni F, EORTC Breast and Quality of Life Groups, et al. Minimally important differences for interpreting EORTC QLQ-C30 scores in patients with advanced breast cancer. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2019;3(3):pkz037.

- Groenvold M, Fayers PM, Petersen MA, et al. Breast cancer patients on adjuvant chemotherapy report a wide range of problems not identified by health-care staff. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2007;103(2):185–195.

- Amidi A, Christensen S, Mehlsen M, et al. Long-term subjective cognitive functioning following adjuvant systemic treatment: 7-9 years follow-up of a nationwide cohort of women treated for primary breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2015;113(5):794–801.

- Broadbent DE, Cooper PF, FitzGerald P, et al. The Cognitive Failures Questionnaire (CFQ) and its correlates. Br J Clin Psychol. 1982;21(1):1–16.

- Bridger RS, Johnsen SÅK, Brasher K. Psychometric properties of the Cognitive Failures Questionnaire. Ergonomics. 2013;56(10):1515–1524.

- Gerlich C, Schuler M, Jelitte M, et al. Prostate cancer patients' quality of life assessments across the primary treatment trajectory: 'True' change or response shift? Acta Oncol. 2016;55(7):814–820.

- Bower JE, Ganz PA, Desmond KA, et al. Fatigue in breast cancer survivors: occurrence, correlates, and impact on quality of life. J Clin Oncol off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2000;18(4):743–753.

- Kindts I, Laenen A, van den Akker M, et al. PROMs following breast-conserving therapy for breast cancer: results from a prospective longitudinal monocentric study. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27(11):4123–4132.

- Lazarewicz MA, Wlodarczyk D, Lundgren S, et al. Diversity in changes of HRQoL over a 1-year period after radiotherapy in Norwegian breast cancer patients: results of cluster analyses. Qual Life Res. 2019;28(6):1521–1530.

- Simard S, Thewes B, Humphris G, et al. Fear of cancer recurrence in adult cancer survivors: a systematic review of quantitative studies. J Cancer Surviv. 2013;7(3):300–322.