Introduction

A special oncological program that enabled fast cancer diagnosis and treatment was introduced in Poland in 2015. Patients in whom a neoplastic disease is suspected receive the so-called DiLO card. It can be issued by (a) a general practitioner, (b) within the framework of outpatient specialist healthcare, or (c) at a hospital. Having obtained the card, the patient is referred for preliminary diagnostic tests and subsequently – if cancer is detected – extended diagnostic tests (assessment of the stage of the disease), followed by a consilium reviewing each individual patient. The DiLO cards provide the public healthcare system with comprehensive information on all oncological patients [Citation1].

The COVID-19 pandemic poses a particular threat to proper oncological treatment [Citation2], especially diagnostics [Citation3]. The first case of the coronavirus in Poland was reported on 4 March 2020. Ten days later, the government imposed a number of restrictions on the society, economy, and healthcare system.

Methods and data

The data used in the presented analysis come from the central payer's system – National Health Fund and refer to all oncological patients in Poland. The scope of data in this study covers the period from the beginning of the program of fast diagnosis and treatment, i.e., from 2015 to 25 May 2020. The DiLO card was introduced in Poland in order to eliminate the limit of services related to oncological treatment and shorten the queue time for diagnosis and treatment to the absolute minimum. This means that the National Health Fund will pay hospitals to perform all the necessary procedures in a given year, and every oncological patient will receive the required treatment. There are no age restrictions on access to treatment as part of fast oncological treatment. The assumption which underlies the DiLO card is that no more than seven weeks may pass from a suspected presence of cancer to final diagnosis and initiation of treatment. This condition is constantly monitored by the payer. About 85% of DiLO cards are executed on time. If the above deadline is not met, the level of financing for delayed oncological diagnostics is reduced to 70%. This is therefore a strong incentive to deliver individual services on time. This fast oncological program is so efficient that patients do not use private diagnoses in this respect – the card can only be issued by a doctor in the public health care system. However, it is possible that oncological treatment takes place without a DiLO card. This may be an unfavorable situation for the patient, as there are no strict deadlines for individual procedures.

Calculations and analyses were performed using statistical packages base and stats in the R programming language [Citation4]. Empirical values were calculated and compared for the period of social distancing policy (March 14–May 25) in 2020 and the same periods in the previous years.

In addition, for the purposes of this paper, a linear regression analysis has also been performed, which answers the following question: How many DiLO cards would have been issued in the examined period in individual health service facilities if the situation in 2020 had been identical to that in the previous years, i.e., there was no COVID-19 pandemic? For this purpose, data for previous years (2015–2019) were used.

Results

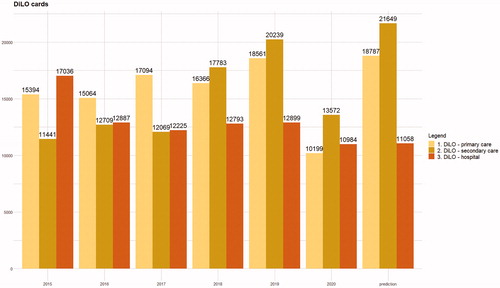

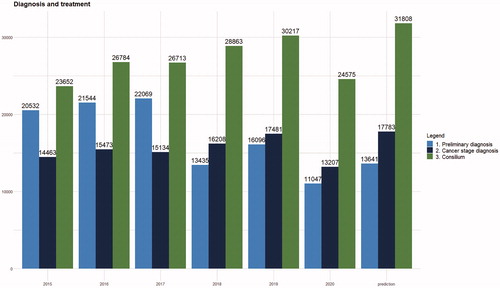

The introduction of the social distancing policy had a significant impact on oncological treatment in Poland. In the analyzed period (), 34,755 DiLO cards were issued, including: 10,199 cards issued by primary health care doctors (29%), 13,572 cards issued within the framework of outpatient specialist health care (39%), and 10,984 cards issued at hospitals (32%). Compared to the same period of the previous year, the number decreased by 33% (34,755 vs. 41,594). In 2020, the number of preliminary diagnoses decreased by 31% as compared to 2019 (), while the number of extended diagnostic procedures decreased by 25% and the number of oncological consiliums decreased by 19%. In other words, patients had much less access to diagnostic tests (although in the case of hospital diagnostics the decrease was the lowest) and – by 20% – to treatment (consilium). The observed declines concerned all patient groups. The median, mean age, and sex of the patients who were issued cards did not differ significantly year to year in the period of 2015–2020.

Figure 2. Preliminary diagnosis, cancer stage diagnosis and oncological consilium conducted in each year in the periods of March 14–May 25.

The largest decline in the absolute numbers of detected neoplasms was observed for: malignant neoplasms of a digestive organ (ICD-10: C15–C26) – the number of cases dropped by 1 231 compared to 2019, malignant neoplasms of the respiratory system and thoracic organs (ICD-10: C30–C39) – the number dropped by 700 cases, and malignant neoplasms of male genital organs (C60–C63) – the number dropped by 911 cases.

The results of the estimates are presented in columns ‘Prediction’. The analysis shows that during the discussed period there was almost no decrease in the number of cards issued in hospital: 11,058 cards were expected to be issued, but actually it was 10,984. The situation was different in the primary care system: 10,199 cards were issued, and according to the regression analysis, the number expected was 18,787 cards (decrease by 46%), and for secondary care − 13,572 cards were issued compared to the expected value of 21,649 issued (decrease by 37%).

Discussion

There are many reasons for the decline in the number of diagnostic services provided to patients holding DiLO cards in the above-mentioned period:

patients’ fear of appointments at medical facilities. It has been emphasized in the media that patients with neoplastic diseases are most at risk of contracting COVID-19 and of facing complications associated with this disease. Patients with a suspicion of cancer, but experiencing mild symptoms, could have decided to postpone the diagnostic procedure;

access to outpatient specialist healthcare was very limited as numerous outpatient clinics suspended their activity, and in the case of primary healthcare, the contact with the physician was limited to telehealth;

the functioning of the national diagnostic programs was limited, e.g., mobile mammography services were closed.

As noted earlier, unlike in other countries, there has been no decline in the number of oncological diagnoses at hospitals [Citation5]. Several factors contributed to this result. First, the network of hospitals in Poland is widely developed. There are 563 hospital beds per 100,000 patients [Citation6], which is one of the higher rates in Europe. Therefore, even the establishment of hospitals dedicated to the treatment of COVID-19 (20 hospitals, with over 10,000 beds, have been established in Poland), did not affect adversely the treatment of other patients, including oncology patients.

Second, while primary and secondary cares were, as a general rule, closed or limited to telemedicine, hospitals – despite the uncertainty in the initial phase of the pandemic – operated normally with emergency rooms and wards open, of course, under a sanitary regime. Thus, the CoV-19 prevention strategy used in primary and secondary care did not completely affect hospitals. While planned operations were canceled or postponed, a patient with an emergency condition could not be refused care. In other words, hospitals have practically become the main health care units that were able to take care of cancer patients.

Third, the financial aspect is also relevant. The services provided to oncological patients are not included in the limit of services for each hospital. Thus, it can be stated that treatment of an oncological patient brings additional income. Therefore, even in the presence of a pandemic situation, it has become profitable to keep the number of oncological patients while significantly reducing the number of patients with other diseases.

Fourth – and this seems to be the most convincing explanation – it was also possible for patients to have had diagnostic tests carried out, but in light of pandemic, if their health condition allowed it, they were released from hospital (there was a tendency to reduce the number of patients in hospitals). When the results of histopathological tests came (already during the pandemic), a DiLO card was issued, which was shown in the statistics during the lockdown period. However, if the lockdown period was longer, a reduced number of DiLO cards could also be expected in hospitals.

Decline in the number of conducted diagnostic procedures may have very serious consequences. There will be a greater number of neoplasms at an advanced stage of development than normally [Citation7], which will result in a decrease in patient survival rate. Once the social distancing policy is lifted, the healthcare system might become overloaded. The number of normally diagnosed patients will be increased by the patients who did not contact their physician during the COVID-19 period.

In conclusion, patients’ and physicians’ safety care during their contact should be increased by implementing strictly defined procedures and sanitary recommendations [Citation8]. It will be helpful to inform patients, e.g., through various social campaigns, that advanced cancer constitutes a much greater threat to health than the risk of possible coronavirus infection. Diagnostics of cancer should not be limited or restricted. Increasing the role of telemedicine and online consultations – where possible – can be considered.

Acknowledgments

This paper has been prepared within the project Maps of Health Needs – Database of Systemic and Implementation Analyses.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Więckowska B, Tolarczyk A. Innowacje w organizacji i finansowaniu leczenia [Innovation in organisation and treatment funding]. In: Więckowska B, Maciejczyk A, editors. Innowacyjna onkologia: potrzeby, mozliwości, system [Innovative oncology: needs, capability, system]. Warszawa: PZWL; 2020. p. 42–52.

- Al-Shamsi HO, Alhazzani W, Alhuraiji A, et al. A practical approach to the management of cancer patients during the novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic: an International Collaborative Group. The Oncologist. 2020;25(6):e936–e945.

- COVID‐19: global consequences for oncology. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:467.

- Team RC. R: a language and environment for statistical computing; 2020. Available from: https://www.R-project.org/

- Dinmohamed AG, Visser O, Verhoeven RHA, et al. Fewer cancer diagnoses during the COVID-19 epidemic in the Netherlands. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(6):750–751.

- Ministry of Health Republic of Poland. basiw.mz.gov.pl [Online]; 2017; [cited 2020 Oct 6]. Available from: https://basiw.mz.gov.pl/index.html#/visualization?id=3404

- Sharpless NE. COVID-19 and cancer. Science. 2020;368(6497):1290–1290.

- COVIDSurg Collaborative. Global guidance for surgical care during the COVID-19 pandemic. Br J Surg. 2020. DOI:10.1002/bjs.11646