Abstract

Background

Patient-reported outcome (PRO) can give information to caregivers and doctors about adverse effects and give real-world data on symptom burden for patients during treatment. We here report PROs from patients with metastatic castration resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) receiving oncological treatment. Our findings are compared with adverse events from published findings in relevant registration studies and we discuss possible applications by looking at the level of interference with usual or daily activities.

Material and methods

An electronic PRO-Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (ePRO-CTCAE) questionnaire, with 41 items corresponding to 22 symptoms/adverse events associated with the treatment regimens commonly used for mCRPC, were collected from 54 patients with mCRPC receiving medical oncological treatment. Eleven symptoms attributing interference with usual or daily living were selected and stratified by antineoplastic treatment administered. The responses were pooled and compared with data from relevant registration studies for docetaxel, cabazitaxel, radium-223 and abiraterone.

Results

168 questionnaires were completed, and among responses from patients receiving docetaxel, 89% of responses shows that fatigue interfered with their usual or daily activities to some degree and 22% to a high or very high degree. In the registration study for docetaxel fatigue is reported with 53% for all grades and 5% for grade 3 or above. For cabazitaxel, radium-223 and abiraterone the percentage of responses with interference of daily activities from fatigue range from 58% to 82%. Between four and six of the eleven chosen PRO-CTCAE symptoms are not reported in the registration studies as common side effects.

Conclusion

PRO may help inform caregivers about symptoms not previously reported, interfering with usual or daily activities but also point to the use of this information to inform new patients. This may help clinicians and patients decide a treatment plan with an acceptable benefit-to-harm ratio.

Background

Regardless if the cancer patient is undergoing standard or experimental treatment, this intervention most often follows a protocol developed with the specific purpose of ensuring uniform and systematic administration of the specific pharmaceutical. Contrary to this situation, the communication between patients and doctors is unstructured and does not follow a protocol, although these situations often serve as the only source of reports of adverse events (AE) occurring during treatment [Citation1].

Thus, it is not surprising that recently published studies have shown discrepancies in AE reporting when comparing information reported by patients and clinicians. Across studies and different cancers, the main finding has been, that clinicians underreport such AE in terms of prevalence, severity and duration. This has been shown regardless of cancer type, treatment modality and symptom scoring [Citation1–6]. These observations form the main motivation and encouragement for establishing a system of patient reported outcomes (PROs), which could serve as AE notifications in all aspects of the treatment of a cancer disease including interference with daily activities, quality of life, health care system contacts, and specific somatic symptoms [Citation5,Citation7–14]. Additionally, treatment information from daily clinical practice is crucial for shared decision making (SDM) and PRO data is suggested as an information aid for this purpose [Citation15]. Real-world evidence is health-care data derived from sources outside the context of traditional clinical studies including the collection of adverse events from daily practice for instance via PROs [Citation16]. Real-world evidence from daily practice can provide information on treatment safety in the general population and thus complement the evidence emerged from clinical studies [Citation17].

PRO has been developed across different treatment areas [Citation10,Citation18], and for oncology the National Cancer Institute (NCI) has developed PRO-CTCAE (Patient Reported Outcome of Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events) to evaluate symptomatic toxicities by self-report in patients participating in clinical cancer trials [Citation5,Citation19], designed as an additional source of information to the commonly applied CTCAE (Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events). The PRO-CTCAE comprises 78 symptoms attributing existence, frequency, and severity of symptomatic toxicities. The large number of items (n = 124) in the PRO-CTCAE library is not relevant for every cancer patient. Hence a selection of items is necessary to make PRO-CTCAE clinically applicable, this selection of items is not uniform but guidelines have emerged for both clinical trials and daily practice [Citation20,Citation21]. Most of these recommendations are based on expert advice, extrapolation from relevant known adverse events and patient surveys [Citation21].

Treatment toxicities in cancer patients may lead to a reduced capacity for carrying out daily activities, which is considered a crucial limiting factor for completing the planned treatment cycles, especially with the elderly and in the palliative setting were frailty is usually more present than in a curative setting, as has been demonstrated with different cancers [Citation2,Citation22–24]. It must be noted that activities of daily living, ADL, is a performance-based measure for specific tasks and should not be confused with the PRO-CTCAE interference attribute [Citation25]. In the PRO-CTCAE setting, the interference with daily or usual activities is a self-perceived measure for a usual or daily activity reported from the patients perspective without a selection of specific tasks. We therefore believe that especially symptoms that interfere with usual or daily activities are crucial to detect and manage.

The aim of this study is to investigate how PRO data can help understand patient experiences during antineoplastic treatment by looking at the level of interference with usual or daily activities in PRO symptoms specific to the metastatic castration resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) population. Further we compare data from this study with toxicity data from relevant phase 3 registration studies [Citation26–29].

Material and methods

An electronic PRO-CTCAE (ePRO-CTCAE) questionnaire, with 41 items corresponding to 22 symptoms/adverse events associated with the regimens commonly used for prostate cancer, were collected from patients with mCRPC, receiving antineoplastic treatment at the Department of Oncology, Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen between 9 March 2015 and 8 June 2015 [Citation9]. To be eligible the patients, in addition to having mCRPC and receiving antineoplastic treatment, had to be able to read, write and speak Danish. As of today (autumn 2020), the products used for antineoplastic treatment in 2015, are still in use as standard treatment.

We have previously published a feasibility study of electronic symptom reporting based on the present observations and here we present a secondary analysis of the original data [Citation9]. Briefly, questionnaires were completed upon each clinic visit, using a tablet computer with software from Ambuflex [Citation30] for selected PRO-CTCAE matching CTCAEs usually reported with medical treatment for mCRPC [Citation9].

The antineoplastic treatment for prostate cancer in this calendar period (9 March 2015 and 8 June 2015) was docetaxel 75 mg/m2 [Citation26] as first line, cabazitaxel 25 mg/m2 [Citation27] as second line, radium-223 [Citation28] or abiraterone [Citation29] as third or fourth line following local hospital guidelines and there were no changes in treatment guidelines during the sampling period [Citation9].

Every third week during treatment, each patient completed the study-specific questionnaire during outpatient clinic visits applying a seven-day recall period [Citation9]. A seven day recall period was chosen due to recommendations on the recall period at this time [Citation5]. From the PRO-responses obtained, we chose those symptoms with attributes interfering with usual or daily activities as those presenting the most relevant information seen from a clinical perspective as this has been reported in smaller studies to be one of the most salient problems for mCRPC patients [Citation31].

By this procedure we identified eleven PRO-CTCAE symptoms with the attribute of interference with usual or daily activities, and subsequently we stratified the data set by antineoplastic agent administered (docetaxel, cabazitaxel, radium-223 and abiraterone) as well as the grade of response. As there are five possible answers describing the severity of the interference attribute (), we graded the responses in the range 0 to 4 with ‘Not at all’ equaling 0, and ‘very much’ equaling 4.

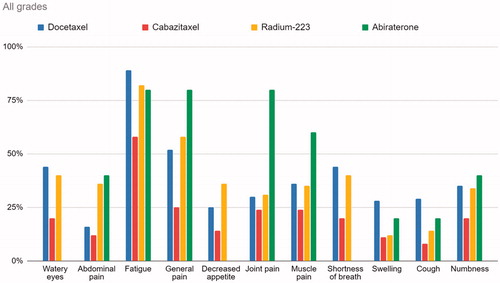

Figure 1. Graph illustrating percentage of PRO-CTCAE responses >0 for the four treatments across symptoms interfering with usual activities.

Table 1. PRO-CTCAE attributes and item structures [Citation5,Citation50].

We have adhered to the ‘The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement’ [Citation32] and a checklist is provided in supplementary material.

Results

Sixty out of 63 eligible patients were approached to participate, and a total of 54 patients completed the questionnaires before each treatment cycle with a total of 168 completed questionnaires (55 questionnaires during docetaxel, 66 during cabazitaxel, 42 during radium-223 and five during abiraterone). None of the patients changed oncological treatment during the sampling period. Median age of the participants was 69 years (range 51–88 years). 18 patients received docetaxel, 18 patients cabazitaxel, 16 patients received radium-223 and two patients received abiratarone [Citation9].

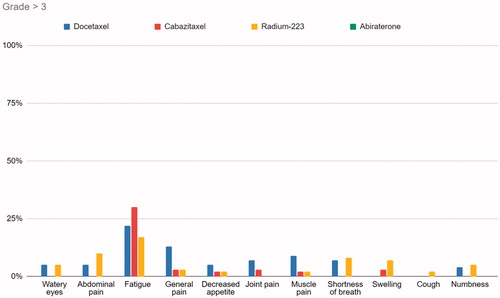

Among responses from patients receiving docetaxel, 89% responded that fatigue, to some degree, interfered with their usual or daily activities, and of all responses 22% to a high or very high degree. For cabazitaxel, radium-223 and abiraterone the responses of fatigue interference range from 58% to 82%. For dyspnea, the interference ranges from no reported interference in the patients receiving abiraterone, to 44% for docetaxel. As for general pain, the interference in the abiraterone group is at 80%, and 25% in the cabazitaxel group. illustrates that fatigue and general pain have the highest scores regarding interference with usual or daily activities. As illustrated in , including scores of grades 3 or higher, fatigue is the most prominent symptom for all treatments, and the Docetaxel and Radium-223 groups experienced more grade 3 or higher responses than that of patients treated with abiraterone and cabazitaxel.

Figure 2. Graph illustrating percentage of PRO-CTCAE responses grade 3 or above, for the four treatments across symptoms interfering with usual activities.

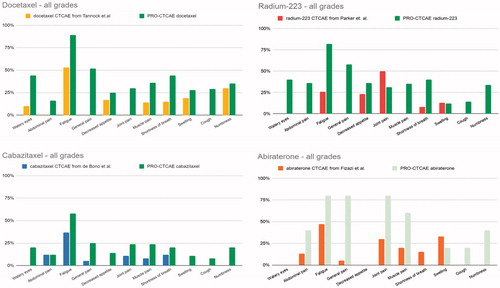

Figure 3. Top left shows percentage of patients receiving docetaxel with CTCAE score >0 published by Tannock et al. and percentage of patient responses with PRO-CTCAE score >0 (green columns) from our dataset. Top right shows percentage of patients receiving radium-223 with CTCAE score >0 published by Parker et al. and percentage of patient responses with PRO-CTCAE score >0 (green columns) from our dataset. Bottom left shows percentage of patients receiving cabazitaxel with CTCAE score >0 published by Bono et al. and percentage of patient responses with PRO-CTCAE score >0 (green columns) from our dataset. Bottom right graph shows percentage of patients receiving abiraterone with CTCAE score >0 published by Fizazi et al. (light green columns represents our PRO-CTCAE responses but are based on only 5 responses by two patients).

In the registration studies fatigue is reported to be among the most frequent side effects, whereas pain is relatively rare (NA for docetaxel and radium-223, and 5% for cabazitaxel and abiraterone) (). Fatigue and dyspnea are, as the only two CTCAEs, reported in all four studies. Fatigue is reported by more than half of the patients receiving first line docetaxel, for cabazitaxel fatigue is reported by 37% [Citation26–29]. For dyspnea the respective registration studies report between 8% and 15% (). Both taxanes have comparable AEs from registration and later studies [Citation33,Citation34]. Between four and six of the eleven chosen PRO-CTCAE symptoms are not reported in the registration studies as common side effects (). The percentage of responses for grade 1–4 is demonstrated in and corresponding symptoms, were available, from each of the registration studies (docetaxel, cabazitaxel, radium-223 and abiraterone) are shown for descriptive comparison [Citation26–29] together with the eleven PRO-CTCAE symptoms.

Table 2. Comparing percentage of PRO-CTCAE responses interfering with usual or daily activities, and matching CTCAE reported by registration studies.

Discussion

This descriptive study in prostate cancer helps to map symptoms experienced by patients, reported to have an interference with daily activities, for different oncological treatments. Additionally, we observed, that several subjective symptoms are not reported in the registration studies of the drugs primarily used for the treatment of patients with metastatic prostate cancer.

There are few published studies on PROs among mCRPC patients undergoing antineoplastic treatment [Citation35], although within the last few years the information in this field has increased as a result of FDA [Citation36] (Food and Drug Administration) and EMA [Citation37,Citation38] (European Medicines Agency) making PRO measures a part of their oncology clinical trial guidelines [Citation36,Citation38–46]. To our knowledge, this is the first study demonstrating ePRO-CTCAEs from mCRPC patients undergoing antineoplastic treatment with a focus on daily or usual activities.

One could expect that later lines of antineoplastic treatment would give more serious side effects due to a general deterioration of health as disease is progressing, and adverse events from earlier lines of treatment become chronic. Contrary to this intuitive expectation, we did not observe this pattern. Except for fatigue, all reported symptoms for second line treatment, with cabazitaxel, seem to have lower impact on daily activities, than in the first line setting with Docetaxel. In 2017 a phase III randomized trial demonstrated comparable effect but reduced toxicity with a lower dosage of cabazitaxel (from 25 mg/m2 to 20 mg/m2), which probably has reduced the AEs for patients today receiving cabazitaxel at the lower dosage [Citation34].

With a seven-day recall period, at the end of each treatment cycle were side effects usually are mildest [Citation47], one would expect a lower symptom burden if the entire treatment cycle would have been in question. Contrary to this we find that there is a higher degree of symptom burden in the patient-reported data than in the phase III registration trials (). This is in line with earlier findings in various cancer populations in real-world datasets versus clinical trials [Citation1]. It is noteworthy that all patient-reported symptoms contain a degree of interference with usual or daily activities, ranging from 8% to 89% of responses across the different treatments and symptoms. Some of these symptoms are not reported to be common adverse events for docetaxel, cabazitaxel, radium-223 or abiraterone in registration studies [Citation26–29].

We suspect that symptoms causing a reduction in usual activities would affect patients to a higher degree than symptoms causing no change in daily routines. If a symptom affects daily routines and tasks, this also affects QoL and more specifically increases anxiety, and general discomfort [Citation13,Citation37,Citation48–50]. Many patients choose to discontinue treatment, due to treatment-induced decline of usual activities, hampering their chance for improved survival or better palliation [Citation2,Citation13,Citation49,Citation51,Citation52]. Maintaining usual or daily activities might be particularly important in the palliative setting in which new treatments have a modest impact on survival [Citation53,Citation54]. Studies show that patients in potentially curative treatments are willing to accept more side effects than patients receiving palliative treatment [Citation55,Citation56]. The real-world information we gather with PRO-CTCAE, help make symptoms that may change the patient’s daily routines visible, this can be used when informing patients about the treatment options. PRO may thus serve as a decision aid in facilitating effective shared decision-making. Further validation is needed to support this suggestion [Citation57,Citation58].

There are limitations to the interpretation of our data due to the small sample size and the pooling of responses from patients. Although 168 questionnaires have been presented, only 54 patients participated in this study, thereby including a single patient's reports multiple times in the analysis. Patients responding to treatment and thus reporting for a longer period will therefore weigh more, potentially skewing the data. Biased interpretation might occur due to the fact that we cannot account for random variations in the frequency of symptoms due to the small sample size. Symptoms reported in this study do not necessarily reflect the antineoplastic treatment administered but could also demonstrate symptoms from the cancer or comorbidities, this would be overcome by a larger randomized trial with a control arm, as in the registration trials. The responses in the abiraterone group are sparse as this treatment shifted to being administered by urologists during the study period and the patients were therefore not followed clinically by the Department of Oncology [Citation9]. We have however chosen to include the patients in this group to present the full dataset of patients in the original study and to show the CTCAEs from the registration study of abiraterone. The present data provide indications of symptom burden reported by PROs but prompts for more prospective collection of data from mCRPC patients.

Conclusion

PRO may help inform caregivers about symptoms interfering with usual or daily activities but also point to the use of this information to inform new patients. This may facilitate and support SDM and help clinicians and patients decide a treatment plan with an acceptable benefit-to-harm ratio.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (18.4 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Atkinson TM, Li Y, Coffey CW, et al. Reliability of adverse symptom event reporting by clinicians. Qual Life Res. 2012;21(7):1159–1164.

- Basch E. The missing voice of patients in drug-safety reporting. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(10):865–869.

- Fromme EK, Eilers KM, Mori M, et al. How accurate is clinician reporting of chemotherapy adverse effects? A comparison with patient-reported symptoms from the Quality-of-Life Questionnaire C30. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(17):3485–3490.

- Pakhomov SV, Jacobsen SJ, Chute CG, et al. Agreement between patient-reported symptoms and their documentation in the medical record. Am J Manag Care. 2008;14(8):530–539.

- Basch E, Reeve BB, Mitchell SA, et al. Development of the national cancer institute’s patient-reported outcomes version of the common terminology criteria for adverse events (PRO-CTCAE). J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106(9):dju244.

- Basch E, Jia X, Heller G, et al. Adverse symptom event reporting by patients vs clinicians: relationships with clinical outcomes. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101(23):1624–1632.

- Kluetz PG, Chingos DT, Basch EM, et al. Patient-reported outcomes in cancer clinical trials: measuring symptomatic adverse events with the National Cancer Institute’s Patient-Reported Outcomes Version of the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (PRO-CTCAE). Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ B. 2016;35:67–73.

- Smith AW, Mitchell SA, De Aguiar C K, et al. News from the NIH: person-centered outcomes measurement: NIH-supported measurement systems to evaluate self-assessed health, functional performance, and symptomatic toxicity. Transl Behav Med. 2016;6(3):470–474.

- Baeksted C, Pappot H, Nissen A, et al. Feasibility and acceptability of electronic symptom surveillance with clinician feedback using the patient-reported outcomes version of common terminology criteria for adverse events (PRO-CTCAE) in Danish prostate cancer patients. J Patient Rep Outcomes. 2017;1(1):1.

- Willke RJ, Burke LB, Erickson P. Measuring treatment impact: a review of patient-reported outcomes and other efficacy endpoints in approved product labels. Control Clin Trials. 2004;25(6):535–552.

- Bruner DW, Bryan CJ, Aaronson N, et al. Issues and challenges with integrating patient-reported outcomes in clinical trials supported by the National Cancer Institute-Sponsored Clinical Trials Networks. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(32):5051–5057.

- Ganz PA, Gotay CC. Use of patient-reported outcomes in phase III cancer treatment trials: lessons learned and future directions. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(32):5063–5069.

- Taarnhøj GA, Johansen C, Lindberg H, et al. Patient reported symptoms associated with quality of life during chemo- or immunotherapy for bladder cancer patients with advanced disease. Cancer Med. 2020;9(9):3078–3087.

- Lipscomb J, Reeve BB, Clauser SB, et al. Patient-reported outcomes assessment in cancer trials: taking stock, moving forward. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(32):5133–5140.

- Martin C, Haaland B, Tward AE, et al. Describing the spectrum of patient reported outcomes after radical prostatectomy: providing information to improve patient counseling and shared decision making. J Urol. 2019;201(4):751–758.

- Nabhan C, Klink A, Prasad V. Real-world evidence – what does it really mean? JAMA Oncol. 2019;5(6):781.

- Sherman RE, Anderson SA, Dal Pan GJ, et al. Real-world evidence – what is it and what can it tell us? N Engl J Med. 2016;375(23):2293–2297. [Internet]. Available from: http://www.nejm.org/doi/10.1056/NEJMsb1609216

- Cella D, Hahn E, Jensen S, et al. Patient-reported outcomes in performance measurement. Research Triangle Park (NC): RTI Press; 2015.

- National Institute of Cancer. The PRO-CTCAE Measurement System [Internet]. Available from: https://healthcaredelivery.cancer.gov/pro-ctcae/measurement.html

- Basch E, Abernethy AP, Mullins CD, et al. Recommendations for incorporating patient-reported outcomes into clinical comparative effectiveness research in adult oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(34):4249–4255.

- Mehran R, Baber U, Dangas G. Guidelines for patient-reported outcomes in clinical trial protocols. JAMA J Am Med Assoc. 2018;319(5):450.

- Hamaker ME, Seynaeve C, Wymenga ANM, et al. Baseline comprehensive geriatric assessment is associated with toxicity and survival in elderly metastatic breast cancer patients receiving single-agent chemotherapy: Results from the OMEGA study of the Dutch Breast Cancer Trialists’ Group. Breast. 2014.

- Ruiz J, Miller AA, Tooze JA, et al. Frailty assessment predicts toxicity during first cycle chemotherapy for advanced lung cancer regardless of chronologic age. J Geriatr Oncol. 2019;10(1):P48–P54.

- Aaldriks AA, van der Geest LGM, Giltay EJ, et al. Frailty and malnutrition predictive of mortality risk in older patients with advanced colorectal cancer receiving chemotherapy. J Geriatr Oncol. 2013;4(3):126–218.

- Lindahl-Jacobsen L, Hansen DG, Waehrens EE, et al. Performance of activities of daily living among hospitalized cancer patients. Scand J Occup Ther. 2015;22(2):137–146.

- Tannock IF, De Wit R, Berry WR, et al. Docetaxel plus prednisone or mitoxantrone plus prednisone for advanced prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(15):1502–1512.

- De Bono JS, Oudard S, Ozguroglu M, et al. Prednisone plus cabazitaxel or mitoxantrone for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer progressing after docetaxel treatment: a randomised open-label trial. Lancet. 2010;376(9747):1147–1154.

- Parker C, Nilsson D, Heinrich S, Helle SI, et al. Alpha emitter radium-223 and survival in metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(3):213–223.

- Fizazi K, Scher HI, Molina A, et al. Abiraterone acetate for treatment of metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: final overall survival analysis of the COU-AA-301 randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(10):983–992.

- Schougaard LMV, Mejdahl CT, Petersen KH, et al. Tele-patient-reported outcomes (telePRO) in clinical practice-effect of patient-initiated versus fixed interval telePRO based outpatient follow-up: study protocol for a pragmatic randomized controlled study. Qual Life Res. 20160;17:83.

- Holmstrom S, Naidoo S, Turnbull J, et al. Symptoms and impacts in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: qualitative findings from patient and physician interviews. Patient. 2019;12(1):57–67.

- Elm V, Altman E, Egger DG, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(8):573–577.

- Oudard S, Fizazi K, Sengeløv L, et al. Cabazitaxel versus docetaxel as first-line therapy for patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: a randomized phase III Trial-FIRSTANA. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(28):3189–3197.

- Eisenberger M, Hardy-Bessard AC, Kim CS, et al. Phase III study comparing a reduced dose of cabazitaxel (20 mg/m2) and the currently approved dose (25 mg/m2) in postdocetaxel patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer - PROSELICA. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(28):3198–3206.

- Di Maio M, Basch E, Bryce J, et al. Patient-reported outcomes in the evaluation of toxicity of anticancer treatments. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2016;13(5):319–325.

- Speight J, Barendse SM. FDA guidance on patient reported outcomes. BMJ. 2010;340(1):c2921–c2921.

- EMA. Reflection paper on the use of patient reported outcome (PRO) measures in oncology studies. European Medicines Agency Science Medicines Health. 2014. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/draft-reflection-paper-use-patient-reported-outcome-pro-measures-oncology-studies_en.pdf

- EMA. The use of patient-reported outcome (PRO) measures in oncology studies [Internet]. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/other/appendix-2-guideline-evaluation-anticancer-medicinal-products-man_en.pdf

- Chi KN, Protheroe A, Rodríguez-Antolín A, et al. Patient-reported outcomes following abiraterone acetate plus prednisone added to androgen deprivation therapy in patients with newly diagnosed metastatic castration-naive prostate cancer (LATITUDE): an international, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19(2):194–206.

- Tombal B, Saad F, Penson D, et al. Patient-reported outcomes following enzalutamide or placebo in men with non-metastatic, castration-resistant prostate cancer (PROSPER): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20(4):556–569.

- Cella D, Traina S, Li T, et al. Relationship between patient-reported outcomes and clinical outcomes in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: post hoc analysis of COU-AA-301 and COU-AA-302. Ann Oncol off J Eur Soc Med Oncol. 2018;29(2):392–397.

- Luo J, Graff JN. Impact of enzalutamide on patient-related outcomes in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: current perspectives. Res Rep Urol. 2016;8:217–224.

- Thiery-Vuillemin A, Poulsen MH, Lagneau E, et al. Impact of abiraterone acetate plus prednisone or enzalutamide on patient-reported outcomes in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: final 12-mo analysis from the observational AQUARiUS study. Eur Urol. 2020;77(3):380–387.

- Dueck AC, Scher HI, Bennett AV, et al. Assessment of adverse events from the patient perspective in a phase 3 metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6(2):e193332.

- Unger JM, Griffin K, Donaldson GW, et al. Patient-reported outcomes for patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer receiving docetaxel and Atrasentan versus docetaxel and placebo in a randomized phase III clinical trial (SWOG S0421). J Patient Rep Outcomes. 2017;2:27.

- Fendler WP, Reinhardt S, Ilhan H, et al. Preliminary experience with dosimetry, response and patient reported outcome after 177Lu-PSMA-617 therapy for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Oncotarget. 2017;8(2):3581–3590.

- Hilarius DL, Kloeg PH, Van Der Wall E, et al. Chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in daily clinical practice: a community hospital-based study. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20(1):107–117.

- Taarnhoj G, Lindberg H, Johansen C, et al. Quality of life in bladder cancer patients receiving chemotherapy: a real life experience. Qual Life Res. 2018;27:S124–S125.

- Colloca G, Colloca P. Health-related quality of life assessment in prospective trials of systemic cytotoxic chemotherapy for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: which instrument we need? Med Oncol. 2011;28(2):519–527.

- Taarnhøj GA, Kennedy FR, Absolom KL, et al. Comparison of EORTC QLQ-C30 and PRO-CTCAETM Questionnaires on six symptom items. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;56(3):421–429.

- Patrick DL, Burke LB, Powers JH, et al. Patient-reported outcomes to support medical product labeling claims: FDA perspective. Value Heal. 2007;10(Suppl 2):S125–S137.

- Basch E, Deal AM, Kris MG, et al. Symptom monitoring with patient-reported outcomes during routine cancer treatment: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(6):557–565.

- Colloca G, Venturino A, Checcaglini F. Patient-reported outcomes after cytotoxic chemotherapy in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: a systematic review. Cancer Treat Rev. 2010;36(6):501–506.

- Clark MJ, Harris N, Griebsch I, et al. Patient-reported outcome labeling claims and measurement approach for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer treatments in the United States and European Union. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2014;12:104.

- Harrington SE, Smith TJ. The role of chemotherapy at the end of life: “when is enough, enough? JAMA J Am Med Assoc. 2008;299(22):2667.

- PEBC’s Ovarian Oncology Guidelines Group. A systematic review of patient values, preferences and expectations for the treatment of recurrent ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2017;146(2):392–398.

- Riikonen JM, Guyatt GH, Kilpeläinen TP, et al. Decision aids for prostate cancer screening choice: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(8):1072–1082.

- Schougaard L, Hjollund N. AmbuFlex-experiences of PRO-based clinical decision-making. Qual Life Res. 2017;26(1):8.