Introduction

A large autopsy study of 500,000 people reported the incidence of primary cardiac and pericardial tumors to be 0.0022% [Citation1]. Primary pericardial mesothelioma (PPM) is a rare type of malignant mesenchymal tissue-derived tumor arising from the pericardium. The prevalences of the three histopathological subtypes (epithelioid, sarcomatoid and biphasic) in the largest contemporary review consisting of 103 published PPM cases were 53%, 24% and 23%, respectively [Citation2].

McGehee et al reported that the median time from clinical presentation to diagnosis was 3 months [Citation2]. The delayed diagnosis has been attributed to the often asymptomatic nature of the disease in its early course [Citation3]. The most common symptoms of PPM are dyspnea, peripheral edema, chest pain, cough and fatigue [Citation2,Citation3].

In their review, McGehee et al. reported that approximately every fifth patient with PPM had been exposed to asbestos, the male-female ratio was 1.5:1 and the median age at diagnosis was 55 years [Citation2]. A total of 81% of the patients were affected with locoregional metastasis predominantly to the mediastinum [Citation2]. The mean time from diagnosis to death was 8.5 ± 13.4 months [Citation2].

Permissions

The patient gave her written informed consent to report her case. We have received our institution’s permission (permission identification: D/2603/07.01.04.05/2019) to compile this work.

Case report

Our patient was a woman in her mid-twenties. Apart from anxiety for which she had been prescribed 20 mg of fluoxetine daily, the patient had no significant medical history or use of prescription medications. She had no cancers in her family, no history of regular smoking or exposure to asbestos. She had previously traveled to South-East and East Asia.

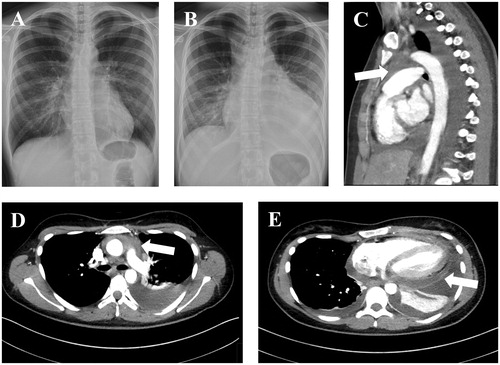

The patient sought help from the primary level health care center for fever, cough and chest pain after the onset of the symptoms in the mid-2010s. Her C-reactive protein (CRP) level was 135 mg/L and a chest radiograph revealed that there was a pleural effusion and her heart was significantly enlarged in comparison to a chest radiograph taken nearly two and a half years previously. She was prescribed amoxicillin for pneumonia. She then revisited the health care center two days later, since her fever still persisted and now she was experiencing pain in her chest. There were no pneumonic infiltrations in the chest radiograph (), but the heart was still enlarged, there was a pleural effusion and the CRP level was now 120 mg/L. She was then referred to our institution (day 0, D0). Low voltages were noted in the electrocardiogram (ECG), but the troponin I level was < 0.02 ug/L (normal range: < 0.06 ug/L) and the CRP level was still 120 mg/L (normal range: < 10 mg/mL). There was a cardiac pretamponade visible in the examination of the transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE). A pericardial catheter was inserted. The patient underwent a whole-body CT (D1, ) that revealed a mass in the upper mediastinum in addition to the presence of pericardial fluid. As the area could not be reached in order to take a tissue sample by a radiological approach, a bone marrow aspirate and biopsy were obtained (D12) but the pathologist reported only reactive changes. The patient was diagnosed with mycoplasma pneumoniae (increased serum IgG antibody levels from 51 (D4) to 97 (D18) and low IgM antibody levels). Thoracoscopic samples were then harvested (D41). Yet again, there were reactive changes. By this time, the CRP level had declined to 13 mg/L and there were no signs of pericardial effusion. Routine controls were terminated.

Figure 1. A chest radiograph (A) showing the normal-sized heart in the radiograph taken almost two and a half years before the patient was referred to our institution. The heart in the radiograph (B) obtained two days after the first appointment in the primary health care center showed an enlarged heart profile. There was an upper mediastinal mass posterior to the sternum (arrows in images C and D) evident in the computed tomography (CT) scan. The mass presented with higher Hounsfield unit values than the pleural or pericardial effusion suggesting that it was solid tissue. The pericardium was enhanced on the CT scan (arrow in image E).

The patient was readmitted to our hospital nearly one year and two months (D519) after the previous checkup. The routine laboratory values were within their expected ranges, but the chest radiograph showed that the heart profile had enlarged again, there was pericardial fluid visible and the pericardium was thickened on TTE. A repeated CT scan (D522) showed nodular changes in pericardium raising the suspicion of a malignancy, or alternatively pericardial tuberculosis. A cardiac MRI was performed (D525); it revealed that the pericardial space was filled with nodular enhancing tissue. The initial pathological report of the pericardial sample that was obtained through an open pericardial biopsy (D530) gave inconclusive findings, i.e., possible mesothelioma or mesothelial proliferation. A subsequent analysis of this sample by a specialist pathologist confirmed the diagnosis of epithelioid mesothelioma (D559). An open cardiac surgery with circulatory bypass was performed (D610), however, there were macroscopic infiltrations to the heart muscle and only the anterior pericardium could be resected. Although the frozen section samples of the brachiocephalic trunk lymph nodes showed no evidence of metastasis, lymph node metastasis was later detected in one of these nodes. The surgical pathological sample of the pericardium confirmed the diagnosis of epithelioid mesothelioma.

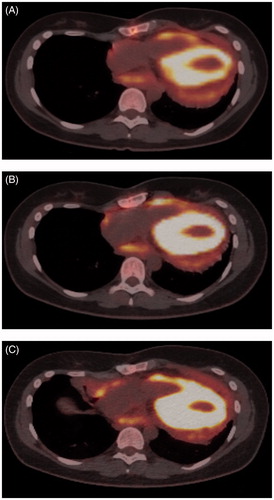

As the disease was advanced and inoperable, the treatment with multiagent chemotherapy with a survival-prolonging objective was initiated. Immuno-oncological treatments were considered, but we could find no support in the literature for this approach to be adopted as the first-line treatment. Furthermore, no suitable trials were available and the patient was PD-L1 negative (with less than 1% of cells staining positive for PD-L1). The first-line treatment was a multidrug combination of 70 mg/m2 of cisplatin, 500 mg/m2 of pemetrexed and 10 mg/kg of bevacizumab with granulocyte stimulating factor (GSF). After the 8th cycle, cisplatin was discontinued to limit its toxicity. The patient was informed about the experimental nature of the immuno-oncological treatments in PPM. In the following treatment lines, pembrolizumab was used as a single agent treatment and in combination with other treatments. During the pembrolizumab treatment, the patient experienced muscle and joint pains and eczema that were attributed to the immune checkpoint inhibitor. Partially because of muscle and joint pains and based on the patient’s request, single-pembrolizumab was discontinued after six cycles. However, these symptoms remained manageable and were alleviated with a course of paracetamol, etoricoxib and low-dose prednisolone (≤ 10 mg/day). Prednisolone was discontinued before her treatments were continued after 5.5 months. The treatments and key imaging findings are presented chronologically in . As the disease progressed through different treatment combinations (), active survival-prolonging cytotoxic treatments were discontinued (D2268). The patient died over six years (D2294) after being admitted to our hospital for the first time.

Figure 2. PET-CT images (A) after three treatment cycles (D755), (B) after seventeen treatment cycles (D1133) and (C) after thirty-six treatment cycles (D1812). The strong fluorodeoxyglucose F 18 uptake of the left ventricle is seen as an oval yellow ring. The uptake had become more pronounced in the pericardium in conjunction with disease progression (images B and C). The used treatments have been listed in .

Table 1. A chronological presentation of treatments given to the patient.

Discussion

Our case illustrates the difficulty of diagnosing this rare disease. Although the patient was quickly referred to our institution, many diagnostic approaches proved futile and it took almost one and a half years from the onset of the symptoms to confirm the pathological diagnosis. A CT scan showing nodular pericardial changes was suggestive of a malignancy, however, cardiac MRI could perhaps have visualized the disease earlier. At the time of surgery, the patient had an inoperable advanced disease; this is common for patients diagnosed with PPM [Citation2].

As complete resection of the tumor proved impossible, the patient received platinum-based chemotherapy with pemetrexed, which also proved beneficial in terms of survival in the report of McGehee et al. [Citation2]. The patient also received bevacizumab, an anti-VEGF therapy; this drug had recently been shown to be efficacious in terms of overall survival in the treatment of pleural mesothelioma [Citation4]. The disease responded to the triple treatment combination (cisplatin, pemetrexed and bevacizumab). After eight cycles containing cisplatin, cisplatin was discontinued to limit its toxicity. The tumor remained stable, as evaluated with PET-CT imaging, during the following eight cycles of pemetrexed and bevacizumab.

There is no agreement on the nature of the second-line treatment for PPM after platinum and pemetrexed based chemotherapy. At the time of the progression through pemetrexed and bevacizumab, there were clinical trials underway evaluating the efficacy of monotherapy with immune checkpoint inhibitors as the second-line treatments of advanced mesothelioma (e.g., the NivoMes study [Citation5], KEYNOTE-028 [Citation6] and the University of Chicago study [Citation7]. It is notable that several studies, e.g., the NivoMes study [Citation5], the University of Chicago study [Citation7] and studies in different settings (e.g., the MAPS2 study [Citation8] and the Canadian Cancer Trials Group study [Citation9]) had not demanded a prerequisite of PD-1 or PD-L1 positivity. Efforts were made to find a suitable clinical trial that could be applied for our patient, but none was available. Nonetheless, encouraged by these clinical trials, pembrolizumab was initiated. The patient received six cycles of pembrolizumab and after a partial response was noted, there was a treatment pause of 5.5 months. As the disease re-activated, pembrolizumab, combined with cisplatin and pemetrexed, was administered for three cycles after which the treatment was de-escalated to single-agent therapy with pembrolizumab for 10 cycles. During these treatment cycles, the disease remained stable. Subsequently, the disease rapidly progressed despite multiple regimes consisting of pembrolizumab combined with other agents.

Several trials of immune checkpoint inhibitors being administered in the second line as single agents and as part of multi-agent treatment regimes in malignant mesothelioma have shown promising results [Citation10]. The mean time from the diagnosis of PPM to death, as discussed earlier, had previously been reported to be much shorter, 8.5 ± 13.4 months [Citation2]. Our patient lived over 6 years after she was first admitted to our hospital and over 4.5 years after the conclusive pathological diagnosis. Although our patient’s long survival is likely partially attributable to her young age and good physical health at the time of diagnosis, our case suggests that some patients with advanced PPM may benefit from immune checkpoint inhibitors after platinum and pemetrexed based chemotherapy.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (896.4 KB)Disclosure statement

Doctors Otso Arponen, Virpi Salo, Annika Lönnberg, Leila Vaalavirta, Hannu Koivu and Paul Nyandoto declare that they have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial or non-financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

References

- Fine G. Primary tumor of the pericardium and heart. Cardiovasc. Clin. 1973;5:208.

- McGehee E, Gerber DE, Reisch J, et al. Treatment and outcomes of primary pericardial mesothelioma: a contemporary review of 103 published cases. Clin Lung Cancer. 2019;20(2):e152–e157.

- Gong W, Ye X, Shi K, et al. Primary malignant pericardial mesothelioma-a rare cause of superior vena cava thrombosis and constrictive pericarditis. J Thorac Dis. 2014;6(12):E272–e275.

- Zalcman G, Mazieres J, Margery J, et al. Bevacizumab for newly diagnosed pleural mesothelioma in the Mesothelioma Avastin Cisplatin Pemetrexed Study (MAPS): a randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2016;387(10026):1405–1414.

- ClinicalTrials.gov [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US). ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02497508, Nivolumab in Patients With Recurrent Malignant Mesothelioma (NivoMes); 2015 June 14 [cited 2020 September 13]. Available from: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02497508.

- ClinicalTrials.gov [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US). ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02054806, Study of Pembrolizumab (MK-3475) in Participants With Advanced Solid Tumors (MK-3475-028/KEYNOTE-28); 2014 February 4; [cited 2020 September 13]. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02054806.

- ClinicalTrials.gov [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US). ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02399371, Pembrolizumab in Treating Patients With Malignant Mesothelioma; 2015 March 26; [cited 2020 September 13]. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02399371.

- ClinicalTrials.gov [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US). ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02716272, Nivolumab Monotherapy or Nivolumab Plus Ipilimumab, for Unresectable Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma (MPM) Patients (MAPS2); 2016 March 23; [cited 2020 September 10]. Available from: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02716272.

- ClinicalTrials.gov [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US). ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02784171, Pembrolizumab in Patients With Advanced Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma; 2016 [cited 2020 September 10]. Available from: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02784171.

- Hotta K, Fujimoto N. Current evidence and future perspectives of immune checkpoint inhibitors in unresectable malignant pleural mesothelioma. J Immunother Cancer. 2020;8(1):e000461.