Abstract

Background

Physical activity (PA) provides many benefits for recovery from cancer treatments. Many older (65+ years) cancer survivors which comprise the majority of the cancer survivor population, do not meet recommended PA guidelines. This study explored the feasibility and acceptability of using audiobooks as part of a 12-week multi-component intervention to increase steps/day, light and moderate-to-vigorous intensity PA among older survivors.

Methods

Twenty older cancer survivors (95% female, mean age = 71.55 years, 90% White, 85% overweight/obese, 75% breast cancer survivors, mean 1.96 years since treatment completion) were randomized into one of the two study groups (Audiobook Group, n = 12, Comparison Group, n = 8). Both study groups were provided a tailored step goal program over the 12-week intervention; weekly step increases were based on a percent increase from baseline. Participant self-monitored their steps using a Fitbit Charge 2. In addition, the Audiobook group were encouraged to listen to audiobooks (downloaded onto a smartphone device via an app available at no cost from the local library) during PA to add enjoyment and increase PA. Regression analyses on steps/day, light and moderate-to-vigorous PA/week and sedentary time/week as assessed by the Actigraph were conducted, after adjusting for Actigraph wear time. Data from the post-intervention questionnaire were summarized.

Results

Overall, majority of participants (89%) stated they were very satisfied with their participation and 100% reported that they were able to maintain their activity upon study completion. Retention rates were high. At post-intervention, there were significant differences favoring the Audiobook group for steps/day and moderate-to-vigorous PA/week. No significant group differences were found for minutes of light intensity PA/week and sedentary time/week.

Conclusion

Piloting the implementation of a sustainable, innovative intervention among older survivors to increase their PA has significance for this group of survivors.

Background

Older cancer survivors (65+ years) represent 62% of the 16.9 million cancer survivors in the U.S [Citation1, Citation2]. These survivors are at high risk for functional decline after a cancer diagnosis not only due to physiologic changes of aging but also due to the additional burden of cancer treatments. The American College of Sports Medicine and the American Cancer Society recommend regular physical activity (at least 150 min of moderate-intensity physical activity [PA] weekly) to help improve recovery and manage long-term and late effects of cancer treatments [Citation3, Citation4]. About 10% of older cancer survivors meet PA guidelines compared with 19% of middle-aged survivors [Citation5]. Older cancer survivors have been shown to improve physical functioning, increase self-reported PA and improve quality of life from distance-based programs delivered via telephone calls and mailed materials [Citation6]. In addition to co-morbidities and functional limitations, these survivors aged 65 + years face barriers to attending on-site exercise program such as limited access to senior-friendly PA resources, transportation and scheduling difficulties, lack of motivation and social support, and insufficient knowledge or skills for developing safe and appropriate physical activities [Citation7]. Data also show that increasing light-intensity PA (2.1–2.9 METS) can reduce the rate of physical function decline in older survivors who are unable or reluctant to start or maintain adequate levels of moderate-intensity PA [Citation8].

Our goal was to develop an innovative PA program, largely distance-based, that would be appealing to older adults (65+ years) and encourage them to be active in their home environment using audiobooks during their PA. Reading books is typically a sedentary behavior but greatly enjoyed among adults [Citation9]. However, listening to books while being active can provide the individual an additional source of enjoyment during light-to-moderate intensity home-based activities such as walking, that are performed individually and are preferred by a majority of cancer survivors [Citation10]. Listening to novels via audiobooks has been used in a prior study in Denmark to promote moderate-intensity aerobic PA among cancer survivors. This 24-week program required participants to listen to an assigned audiobook, use a pedometer during walking and then attend a book-club meeting every 3 weeks. The pilot study had high attrition chiefly due to the selection of books (e.g. ‘too bleak’) and patients were unable to attend the book club meetings [Citation11]. Some participants reported that moving around while listening to a book made doing an otherwise sedentary activity of reading, legitimate. For others, regular walking while listening to the books was described as a unique experience connecting the mind with the body. The researchers concluded that combining the use of audiobooks with PA contributed to increased PA and the perception of PA as meaningful and enjoyable. Although not linked to PA, additional research has shown that interventions based on theories and techniques from stories, story reading and/or story telling may reduce depressive symptoms [Citation12], promote coping and encouraged PA in cancer survivors [Citation13].

Furthermore, additional work has explored the benefits of a low-intensity home-based PA program among cancer survivors. van Waart and colleagues compared the possible benefits of a low-intensity PA program with a moderate-to-high intensity program and usual care group among breast cancer survivors (mean age= 50.7 years) while completing adjuvant chemotherapy [Citation14]. Participants in the low-intensity PA program followed a self-managed, individualized program. While the moderate-to-high intensity PA program had the greatest effect on cardiorespiratory fitness, muscle strength, and fatigue, participating in the low-intensity PA program yielded positive effects relating to fatigue and favorable return to work rates [Citation14]. Recently, Møller and colleagues compared a 12-week home-based pedometer intervention with a supervised intervention (cardiorespiratory and resistance training) to compare physiological and patient reported outcomes among previously inactive breast cancer survivors (mean age = 51.7 years) [Citation15]. Specifically, the home-based pedometer intervention aimed for its participants to achieve 7,500 steps/day at a low-to-moderate intensity. At follow-up both groups (home-based and supervised) saw beneficial effects on cardiorespiratory fitness and encouraged PA participation during and following adjuvant chemotherapy [Citation15]. In sum, the contributions of a low-intensity PA program to improve health outcomes, specifically among those who are unable to adopt and maintain a moderate-to-vigorous PA program, should not be overlooked.

Informed by this prior work, we developed our proposed multi-component intervention (Audiobook). The study team in Denmark [Citation11] concluded that the book selection, and the format and supervision of book club meetings would need to be considered before larger trials can be initiated. We planned to offer participants a choice of audiobooks among a list of recommended books (variety of genres), and book club meetings were not required. We planned to use audiobooks, in addition, to established theory-based components of PA promotion (behavioral and social cognitive theoriesCitation16]: education about various intensities of PA, setting small, easily achievable PA goals, self-monitoring of PA and feedback on PA participation, to encourage older cancer survivors to become physically active. In developing this multi-component intervention we also used the guidelines issued by the 2015 Cancer and Aging Research Group [Citation17].

This pilot randomized controlled study examined the feasibility, acceptability and preliminary effects of a ‘novel’ multi-component PA program on survivors’ daily steps and weekly light, moderate-to-vigorous PA, and sedentary time (assessed via accelerometer). We expected that, at post-intervention, Audiobook participants would increase their step count and their light and moderate-to-vigorous intensity PA and reduce sitting time vs. the Comparison Group participants. We also planned to obtain feedback from participants on their experience with the intervention components.

Methods

Study design

The intervention was tested using a longitudinal two-group randomized controlled design with assessments at pre- and post-intervention (12 weeks).

Sample and participant recruitment

Older cancer survivors (≥65 years) were asked to participate in the study. Participants were recruited from Prisma Health Upstate (Greenville, SC) through referrals from oncology healthcare providers. Additionally, the research team sent informational email or letters to patients who chose not to participate in an on-site exercise program, those who had completed the on-site program >6 months previously and from a data-base of patients who had received services for the Center for Integrative Oncology Services at Prisma Health Upstate. The study received approval from the Prisma Health Center-Upstate Institutional Review Board (Pro00076848). Participant recruitment began in October 2018 and ended in December 2019.

Interested participants were asked to contact the study’s on-site Research Coordinator (RC) who described the study and obtained verbal consent before completing the eligibility screen. Patients were initially deemed eligible if they: a) were ≥65 years of age, b) diagnosed with Stage 1–3 cancer. In addition, we included patients with Stage 0 breast cancers and any Stage 4 cancer without evidence of disease, c) recently (<5 years) completed cancer treatment (i.e. surgery, chemotherapy, and/or radiation; patients on endocrine or maintenance immune therapies were eligible), d) were able to walk unassisted, e) were interested in increasing their PA, f) had a smartphone device (Android or I-phone), g) could hear audiobooks, and h) had good vision. If eligible at screen, the participant was scheduled for a baseline visit.

The study team did expand recruitment approaches and inclusion criteria over the course of the study (from initiation to the closing of study) to allow for a larger population of cancer survivors. These changes included informational mailings sent to individuals who had lapsed into activity after completing the Moving On exercise rehab program, 6 months previously, and, including individuals: a) who expressed a desire/intention to increase their PA, regardless of current PA, b) with Stage 0 breast cancer diagnosis, and c) who had completed treatment with ≤5 years (previously had been ≤3 years). These changes facilitated patient enrollment.

Baseline measures

All eligible participants were invited to attend a baseline visit during which they were provided an overview of the study which included a visual aid and verbal description to ensure the participants were knowledgeable of the study requirements. If they agreed to participate, they provided written informed consent. After the informed consent was obtained, participants completed questionnaires and received a Fitbit and Actigraph as described below.

Questionnaires:

Participant demographics: Demographic information was collected at baseline (). Additionally, disease and treatment history were collected (e.g., cancer type, stage, diagnosis date, and treatment completion dates) and verified from medical records to ensure eligibility criteria were met.

Table 1. Descriptive characteristics of the groups.

PA Measures:

Fitbit: Participants received a Fitbit Charge 2 to wear for 7-days at baseline and post-intervention. Participants were also asked to wear the Fitbit throughout the 12-week study to measure their steps to ensure they were reaching their weekly goals. The Fitbit was used primarily as an intervention component.

Actigraph: All participants were asked to wear an Actigraph accelerometer (GT3x) at the waist for 7 days at baseline and post-intervention, as an objective measure of PA. The Actigraph measures activity counts, steps and time spent in sedentary behavior during periods of wear time. Software is used for categorizing the counts into light, moderate, hard, or very hard categories. Activity was defined by activity/counts per minute, that is light (100–1951 counts/min), moderate (1952–5724 counts/min), hard (5725–9499 counts/min) and very hard intensity PA (>9499 counts/min) [Citation18]. For this study, we were interested in steps/day, weekly light, and moderate-to-vigorous activity and time spent sedentary.

Upon successful 7-day wear of the Fitbit and Actigraph device, participants returned for their second baseline visit. At this visit, participants were randomized into either the Audiobook group or the Comparison group. The randomization sequence was completed by the statistician. Block randomization was used based on the following criteria: 1) sex [male vs. female], 2) body mass index [BMI] category [normal vs. overweight/obese], and 3) mean steps at baseline [≤2,500 vs. >2,500 daily step mean]). The RC enrolled and assigned participants to their assigned intervention.

Intervention conditions

Following randomization, participants in both groups received an educational session from the RC. The educational session took approximately 60 min for the Comparison Group and 90 min for Audiobook participants. During the education session, the RC discussed ways to increase steps and provided a list of places to walk in their local area. As this was a home-based study, the RC also reviewed safety precautions for PA. All participants received the step goal information. The weekly step goal increase was tailored to the baseline Fitbit step average collected during the 7-day baseline assessment. While both the Fitbit and Actigraph were worn during the 7-day assessment, we selected to use the steps collected via the Fitbit device to ensure consistency, as the participant used the Fitbit to monitor their steps each week during the intervention. Given that older cancer survivors are less active, we did not set a goal of 10,000 steps/day. The weekly step goal increase was broken down as follows: <2,000 steps/week at baseline = 20% increase in steps/week; 3,000 steps/week at baseline = 15% increase in steps/week; 4,000 steps/week at baseline = 10% increase in steps/week; >5,000 steps/week at baseline = 5% increase in steps/week. For example, if a participant average 3,500 steps during their baseline, their week one step goal was 4,025 steps/day (15% increase). Participants were asked to track their steps each day. If the step goal was not met five out of the seven days during that week, the participant was asked to go back to the step goals from the previous week [Citation11,Citation19]. The participant was taught how to change step goals over the coming weeks based on their success in achieving the previous goal.

Audiobook group

After the step goals were reviewed, the RC demonstrated and instructed the Audiobook participants on how to search, select and download audiobooks from the Hoopla phone application during the education session. This application is accessible at no cost through the Greenville County Public Library and was downloaded to the participant’s smartphone. Audiobook participants were encouraged to listen to audiobooks while they engaged in structured PA such as scheduled walks, during chores, etc. We provided library membership to those who did not live in the county to ensure participants had access to the Hoopla app.

Participants were asked to wear the Fitbit throughout the day. Weekly PA logs were provided to participants for the 12-week program and they were asked to do the following: 1) record the number of steps accumulated per day, and 2) adjust their step goals every week on the Fitbit app and on the PA calendar log based on their previous week’s step count. If the participant experienced any acute health symptoms such as shortness of breath or chest pain, they were instructed to stop PA and seek immediate medical attention. They were instructed to contact research staff when able to apprise the study team of the events.

Audiobook participants received bi-weekly feedback reports showing their mean steps/week over two weeks compared to the previous two weeks, badges earned for distance traveled, and a book recommendation. We expected that these book recommendations and step count feedback would help guide the participant with his/her audiobook selection and increase their step count. In addition to the feedback reports, these participants received 12 PA tip sheets and 12 cancer survivorship tip sheets (two tip sheets for each week of the 12-week program). PA tip sheets were tailored for older adults and included ways to improve balance and stretching, while the cancer survivorship tip sheets provided information on topics such as how to manage stress and ways to improve sleep. The PA and cancer survivorship tip sheets were mailed or emailed (dependent on participant preference) bi-weekly.

Comparison group

Similar to the Audiobook group, these participants were also encouraged to increase their steps/week and received instructions on how to set step goals for each week. Participants wore the Fitbit device throughout the day but did not receive training or assistance for listening to the audiobooks from the library. Similar to the Audiobook group, the Comparison Group received bi-weekly feedback reports showing their mean steps/week but they did not include the audiobook recommendations. However, they received the same cancer survivorship and PA tip sheets at the same frequency as the Audiobook Group.

Post-Intervention assessments

The 12-week assessments followed the same procedures as baseline. Prior to the in-person visit, the RC mailed the Actigraph to the participants with instructions on how and when to wear it for the post-intervention assessment. At the post-intervention visit, the RC collected the Actigraph and downloaded the data. Participants were allowed to keep the Fitbit as an incentive and the shared Fitbit account was turned over to them during the post-intervention visit.

All participants completed a post-intervention evaluation that assessed their satisfaction with and helpfulness of each component of the intervention (activity tracker, setting goals, feedback reports, and PA and cancer survivorship tip sheets) (see ). In addition, Audiobook participants were asked to evaluate their overall experience, perceived enjoyment of the books during PA, number of books used, enjoyment of PA, etc. Perceived usefulness and satisfaction with the audiobooks to increase activity were assessed using separate 5-item rating scales (0 = not at all useful, 5 = very useful).

Analyses

Demographics of our sample are presented in , where we found no significant differences in unadjusted comparisons between the groups on demographic variables. Our primary goal was to assess acceptability and feasibility of the Audiobook intervention and to explore group-level outcomes and obtain estimates of standardized effect sizes (absolute effect sizes divided by the standard deviation of the estimates otherwise known as Cohen’s effect) [Citation20].

We evaluated whether there was a significant difference in pre to post PA (as assessed by the Actigraph) within a treatment group in a stratified regression model (stratified per treatment group) adjusting for Actigraph wear time. We evaluated whether the average post-pre differences differed across the two groups in a regression model of the within-participant differences adjusting for Actigraph wear time.

Results

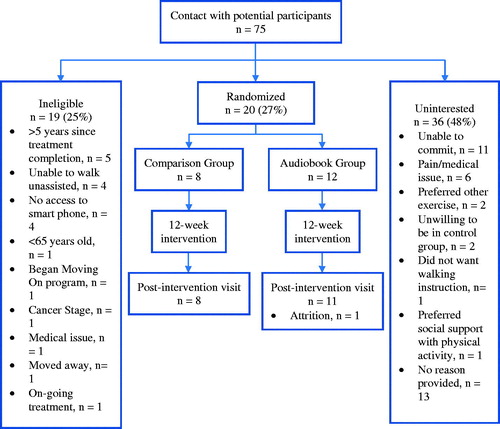

There were 75 participants who contacted the RC. Of these, 19 were ineligible and 36 participants were uninterested (see for reasons) and 20 participants were randomized to the study. These participants (95% female, mean age = 71.55 years, 90% White, 85% overweight/obese, 75% breast cancer survivors, mean 1.96 years since treatment completion) were randomized into one of the two study groups (Audiobook Group, n = 12, Comparison Group, n = 8). All but one participant (dropped out because of a fractured bone in her foot, unrelated to study participation) completed the post-intervention assessments.

The primary goal was to determine whether there would be a difference in the daily number of steps per day between groups at post-intervention. We found a significant difference (p = .0187) in the change from baseline to the end of the study where participants in the Audiobook Group added substantially more steps (1487.19) per day than participants in the Comparison Group (−1209.18) (Cohen’s effect size 1.08). On examining group differences in light-intensity and sedentary time, we found no differences between groups. However, there were significant group differences in moderate-to-vigorous PA minutes/week favoring the Audiobook group (Cohen’s effect size 0.9). (See ).

Table 2. Group comparisons using Actigraph data over 7 days.

Post-intervention evaluation data were provided by 19 participants. 89% of participants (n = 16) were very satisfied with their study participation, and 100% reported that they could maintain PA after the study ended. Their ratings of the intervention components were as follows: 100% found the Fitbit to be helpful for PA, 85% rated the educational session as providing them sufficient information, 84% rated the PA feedback reports as moderately-to-very helpful, and 79% rated the tip sheets as moderately-to-very helpful. Seventy percent of the Audiobook group (7/10) reported that it was easy/very easy to use the Hoopla app, and they listened to a mean of 5.62 audiobooks during the study. Eighty-nine percent of the sample (17/19) wore the Fitbit on >90% of study days, demonstrating high adherence to wearing the Fitbit. Additional feedback from the participants can be seen in .

Table 3. Post-intervention feedback.

Discussion

This pilot study aimed at assessing the feasibility and acceptability of a multi-component intervention to increase steps, light and moderate-intensity PA among older cancer survivors. Consistent with our hypothesis, the Audiobook group outperformed the Comparison Group on steps per day, as seen in accelerometer data. They also showed greater participation in weekly minutes of moderate-to-vigorous intensity PA. These data are very promising, given that the baseline data showed that mean daily step count was low among this group of cancer survivors. In translating PA guidelines into steps for older adults, Tudor-Locke and others have recommended that older adults with disabilities and chronic diseases should aim for 6,500-8,500 steps/day [Citation19]. Given that our sample were older adults treated for cancer, the progress in steps/day shown by the Audiobook Group at the end of 12 weeks is quite remarkable.

Interestingly, the Audiobook Group also significantly outperformed the Comparison Group in moderate-to-vigorous intensity weekly PA but not for light-intensity weekly PA. These results suggest that the increase in daily steps among Audiobook Group participants showed they were walking at brisk pace reflecting the increase in moderate-to-vigorous intensity PA.

Our data showed that recruitment of older adults was challenging with 20 participants recruited from among 75 participants who were screened. The most common reason patients declined to enter the study was the 12-week time commitment due to on-going family issues that would preclude participation. Surprisingly, only four interested participants were unable to participate in the study due to not having access to a smartphone. These data support access to technology that was needed for intervention delivery. As a pilot-test, the study was limited to individuals who were followed at one of the nine Cancer Institute locations at Prisma Health. Individuals were prescreened and selected from patients seen in the Integrative Oncology and Survivorship clinic. This could have limited the willingness of an individual to participate as some patients did not have their main oncology healthcare provider reinforcing the potential benefits of PA intervention.

Our post-intervention data show that participants were satisfied with the overall study and rated many of the intervention components favorably. Participants in both groups reported that the Fitbit made them more aware of their steps throughout the day (41%) and many participated in structured walks to ensure their daily steps goals were met (84%). A large majority of the sample (89%) wore the activity tracker on >90% of the study days. The majority of study participants endorsed that the educational session at study enrollment provided them sufficient information to become active (83% in the Audiobook group and 88% in Comparison group). All participants (100%) who completed the survey responded positively when asked if they feel they could maintain their steps outside of the program.

Audiobook group participants responded favorably to using the audiobooks to increase their steps. A majority of Audiobook participants (60%) felt that the audiobooks gave them something to focus on participating in structured walks. We were pleasantly surprised to find that using the Hoopla app and downloading books was a challenge to only two participants. Lastly, although we asked participants to use the audiobooks during PA, there were a few participants who listened to the books at other times, for example, to aid relaxation. A study limitation was that we did not assess each participant’s comfort level and familiarity with technology at study enrollment. We were not able to track usage of the Hoopla app. Future studies should consider assessing these aspects, monitor Fitbit use and prompt participants to resume wearing the Fitbit, if usage declines.

Finally, we are not sure why there was an overall decrease in steps/day from baseline to post-intervention in the Comparison group who received the same intervention as the Audiobook Group except for the Audiobook component. It may be that, once the novelty of the Fitbit monitor wore off, participants returned to their inactive lifestyle. There were no significant differences between groups on demographic variables and steps/day at baseline. With a small sample size, we were not powered to test interactions between these variables and PA outcomes.

Our pilot study results (quantitative and qualitative) support the feasibility of a multi-component intervention (activity tracker, audiobooks, educational session, feedback reports and tip sheets) that was largely distance-based, to help older adults to become more active in their home environments. Our partnership with the county library worked smoothly. Our participant retention was high compared to the prior study [Citation11] and we speculate that our higher retention was due to the absence of a book club meeting requirement and participants were free to listen to an audiobook of their choice. We recognize that the daily step count at post-intervention was below 10,000 steps that has been promoted for healthy adults but is in keeping with recommendations for older adults with chronic disease or disabilities [Citation17].

The strengths of the study are its longitudinal design, the focus on steps which is a concrete easy-to understand and feasible for older cancer survivors, obtaining objective assessments of steps and PA, the use of a novel component available through their local library that allowed participants to freely access audiobooks and strong participant retention. The study is limited by a small, relatively homogenous sample (white, female and largely, breast cancer survivors, living in urban areas), and strict inclusion criteria that may have limited our ability to recruit participants, although we did modify our criteria over time to improve enrollment.

In conclusion, offering novel intervention components that are inexpensive, largely distance-based and can enhance enjoyment of PA could encourage older survivors to become active in and around their home environments. The study did encounter challenges to participant enrollment, but the interventions were feasible and acceptable to the select group of study participants for whom it was safe to exercise without on-site supervision, the distance-based approach was practical and the partnership with the local County library was successful. The use of Audiobooks offered through a community resource also allows for sustainability of this component. Our results will be used to develop a large-scale randomized trial to promote PA among older cancer survivors.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (219.5 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors appreciate the support and assistance of the Greenville County Public Library and its staff.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- American Cancer Society. Cancer treatment and survivorship facts and figures 2016-2017. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2016.

- Bluethmann SM, Mariotto AB, Rowland JH. Anticipating the "Silver Tsunami": prevalence trajectories and comorbidity burden among older cancer survivors in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2016;25(7):1029–1036.

- Schmitz KH, Courneya KS, Matthews C, American College of Sports Medicine, et al. American College of Sports Medicine roundtable on exercise guidelines for cancer survivors. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2010;42(7):1409–1426.

- Rock CL, Doyle C, Demark-Wahnefried W, et al. Nutrition and physical activity guidelines for cancer survivors. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62(4):243–274.

- Tarasenko Y, Chen C, Schoenberg N. Self-reported physical activity levels of older cancer survivors: results from the 2014 National Health Interview Survey. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(2):e39–e44.

- Morey MC, Snyder DC, Sloane R, et al. Effects of home-based diet and exercise on functional outcomes among older, overweight long-term cancer survivors: RENEW: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;301(18):1883–1891.

- Hong Y, Dahlke DV, Ory M, et al. Designing iCanFit: a mobile-enabled web application to promote physical activity for older cancer survivors. JMIR Res Protoc. 2013;2(1):e12

- Blair CK, Morey MC, Desmond RA, et al. Light-intensity activity attenuates functional decline in older cancer survivors. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2014;46(7):1375–1383.

- Research E. New survey says libraries are feeling the audiobook love. 2017. [cited 2021 Feb 27]. Available from: http://www.booklistreader.com/2017/06/07/audiobooks.

- Jones LW, Courneya KS. Exercise counseling and programming preferences of cancer survivors. Cancer Pract. 2002;10(4):208–215.

- Hammer NM, Egestad LK, Nielsen SG, et al. Feasibility and acceptability of active book clubs in cancer survivors - an explorative investigation. Acta Oncol. 2017;56(3):471–478.

- Dowrick C, Billington J, Robinson J, et al. Get into reading as an intervention for common mental health problems: exploring catalysts for change. Med Humanit. 2012;38(1):15–20.

- Midtgaard J, Christensen JF, Tolver A, et al. Efficacy of multimodal exercise-based rehabilitation on physical activity, cardiorespiratory fitness, and patient-reported outcomes in cancer survivors: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Oncol. 2013;24(9):2267–2273.

- van Waart H, Stuiver MM, van Harten WH, et al. Effect of low-intensity physical activity and moderate- to high-intensity physical exercise during adjuvant chemotherapy on physical fitness, fatigue, and chemotherapy completion rates: results of the PACES Randomized Clinical Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(17):1918–1927.

- Moller T, Andersen C, Lillelund C, et al. Physical deterioration and adaptive recovery in physically inactive breast cancer patients during adjuvant chemotherapy: a randomised controlled trial. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):9710.

- Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: a social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1986.

- Kilari D, Soto-Perez-de-Celis E, Mohile SG, et al. Designing exercise clinical trials for older adults with cancer: Recommendations from 2015 Cancer and Aging Research Group NCI U13 Meeting. J Geriatr Oncol. 2016;7(4):293–304.

- Freedson PS, Melanson E, Sirard J. Calibration of the Computer Science and Applications, Inc. accelerometer. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1998;30(5):777–781.

- Tudor-Locke C, Craig CL, Aoyagi Y, et al. How many steps/day are enough? For older adults and special populations. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2011;8:80.

- Cohen J. A power primer. Psychol Bull. 1992;112(1):155–159.