Abstract

Background

The completeness and accuracy of the registration of synchronous metastases and recurrences in the Swedish Colorectal Cancer Registry has not been investigated. Knowing how accurate these parameters are in the registry is a prerequisite to adequately measure the current recurrence risk.

Methods

All charts for patients diagnosed with stage I–III colorectal cancer (CRC) in two regions were reviewed. In one of the regions, all registrations of synchronous metastases were similarly investigated. After the database had been corrected, recurrence risk in colon cancer was calculated stratified by risk group as suggested by ESMO in 2020.

Results

In patients operated upon more than five years ago (N = 1235), there were 20 (1.6%) recurrences not reported. In more recent patients, more recurrences were unreported (4.0%). Few synchronous metastases were wrongly registered (3.6%) and, likewise, few synchronous metastases were not registered (about 1%). The five-year recurrence risk in stage II was 6% for low-risk, 11% for intermediate risk, and 23% for high-risk colon cancer patients. In stage III, it was 25% in low- and 45% in high-risk patients. Incorporation of risk factors in stage III modified the risks substantially even if this is not considered by ESMO. Adjuvant chemotherapy lowered the risk in stage III but not to any relevant extent in stage II.

Conclusion

The registration of recurrences in the registry after 5 years is accurate to between 1 and 2% but less accurate earlier. A small number of unreported recurrences and falsely reported recurrences were discovered in the chart review. The recurrence risk in this validated and updated patient series matches what has been recently reported, except for the risk of recurrence in stage II low risk colon cancers which seem to be even a few percentage points lower (6 vs. 9%).

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most common cancers worldwide [Citation1]. At diagnosis, 20–25% have metastatic disease and another 20–25% will have recurrent disease, thus, between 40 and 50% ultimately will have locally recurrent or metastatic disease [Citation2–5]. Although much progress has been seen in the treatment of metastatic CRC, most of these patients die from their disease. To prevent recurrences, many patients with colon cancer receive postoperative chemotherapy and many patients with rectal cancer receive preoperative (chemo)radiotherapy and occasionally postoperative chemotherapy since these treatments reduce recurrences to such an extent that disease-free and overall survival (OS) are improved [Citation6–8].

Evidence indicates that the recurrence risk after CRC surgery has decreased during the past decades due to improvements in care [Citation9–11]. Better staging detects smaller distant metastases resulting in fewer recurrences in those operated. Improved surgical techniques [Citation12–14] also reduce recurrence risks. Finally, improved examination of the surgical specimen does not reduce recurrence risks, but results in fewer recurrences in each pathological stage; stage migration or Will-Rogers phenomenon [Citation15]. In the entire Swedish population of 14,325 operated stage I–III colon cancer patients diagnosed between 2007 and 2012 fewer recurrences than historically were reported [Citation3]. In rectal cancer, local recurrence rates have decreased to about 5% but it is unknown if systemic recurrences have similarly decreased [Citation16].

The Swedish Colorectal Cancer Registry (SCRCR) has been running since 1996 for rectal cancer and 2007 for colon cancer with almost complete reporting [Citation2,Citation17]. The registry contains demographic, staging, and surgical treatments with high accuracy [Citation18]. Since 2011, neoadjuvant and adjuvant treatment and treatment for metastatic disease can be registered. The accuracy of the reporting of recurrences in the registry is not known. According to the National Care Programme from 2008, updated in 2016, staging using preferably computed tomography (CT) should be performed of the primary tumor (MRI for rectal tumors), liver and lungs. During follow-up, clinical investigation, CT of the abdomen and lungs and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) are mandatory after 1 and 3 years. Recurrences should be reported once they have been diagnosed. A reminder is sent to the surgical departments after 3 and 5 years to report any recurrence since last follow-up. If not reported before, the oncologist can also report whether a recurrence has occurred. Thus, most recurrences have probably been recorded, but to claim that recurrence risks are lower than in the past, it is necessary to estimate how complete and accurate the registration is.

Proper knowledge of recurrence risks is important to evaluate if neoadjuvant or adjuvant therapy is motivated. A surgery alone group has, with one exception [Citation19], not been present in trials performed for several decades. Patients included in clinical trials are selected and not representative of the background populations [Citation20–22]. Population-based registries seldom include recurrence data and, if they do, they are unreliable, likely underestimating the risks [Citation23,Citation24]. Survival is recorded in registries but overestimates the need of adjuvant chemotherapy since deaths from other causes than CRC cannot be prevented by adjuvant chemotherapy.

The aim was primarily to validate the recurrence data in two Swedish regions. In one region, where recurrence risk after colon cancer surgery has previously been estimated [Citation3,Citation25], a special interest in registry-based CRC research made representativity questionable. In that region, registration of synchronous metastases was also validated. A further aim was to update stage-specific recurrence risks and evaluate the risk factors recommended by ESMO [Citation8] in colon cancer with validated recurrence data after long follow-up.

Patients and methods

The Uppsala and Gävleborg regions

In the Uppsala region (375,000 inhabitants in 2018), Uppsala University Hospital, operates all CRCs from patients living in the region and all oncological treatments are given in or directed from Uppsala. In Gävleborg (286,000 in 2018), two hospitals, Gävle and Hudiksvall operate these patients and oncological treatments are given in or directed from Gävle. In both regions, 98–100% of diagnosed CRCs have been reported to the SCRCR [Citation26].

Patients

All patients diagnosed with CRC between January 2010 and December 2018 while living in the Uppsala region, and patients who had surgery for stage I–III cancers living in Gävleborg during the same period were included. Information about stage at diagnosis, treatments, whether a recurrence had been registered and vital status were obtained from the SCRCR in April and June 2020 for the Uppsala and Gävleborg regions, respectively. The medical records of patients with registered metastases at diagnosis (Uppsala), registered recurrences and recurrence-free (Uppsala and Gävleborg) were scrutinized independently by two abstractors during the first half of 2020. In case of discrepancies and in all cases where the evaluation resulted in a difference against what was registered, a joint evaluation was done including the senior author (BG) and a consensus decision made. Metastasis was considered synchronous if detected at the diagnosis of the primary tumor or at the latest at surgery if operated electively or during the staging performed within a month after an emergency surgery. If a registered metastasis or recurrence was surgically removed and found to be another diagnosis, the registration default was easy to evaluate. We considered patients with lack of progression without any treatment for at least 2 years to be non-recurrent, whereas if treated with chemotherapy or radiotherapy and disappearing as recurrent. Occurrence of a lesion on radiology but not typical for metastases in a patient rapidly dying afterwards was considered as recurrent disease even if this was not ascertained. Diseased patients without notes of recurrent disease in the records, most of them with notations of other severe diseases, were considered recurrence-free.

Since the purpose was to identify an accurate patient population at risk of recurrence with complete and correct information of whether a recurrence had occurred or not for studies on population-based recurrence risks, we chose to scrutinize the records of all patients in the populations and not a random sample, as recommended [Citation27–29]. Further, it was inappropriate to make a new abstraction and compare to registry data since the clinical records at the initial evaluation, for example, done at a multidisciplinary team conference, was not always correct and this could easily be missed by the abstractors.

Statistics

Missed recurrences were tabulated by year of diagnosis and graphically with a Kaplan–Meier plot with censoring for loss to follow-up and death. Patients in colon cancer stages II and III were classified as low, intermediate (only stage II) and high risk according to ESMO risk factors (perioperative obstruction, pT4, <12 investigated nodes, high grade malignancy, lympho-vascular invasion, and perineural invasion). Three- and five-year recurrence rates were calculated with and without adjuvant treatment stratified by risk group using the Kaplan–Meier method, again with censoring for loss to follow-up and death. Recurrence rates for rectal cancer patients were not calculated since detailed information about neoadjuvant treatments and the time to surgery, influencing pathological stage, was not available from Gävleborg. The contribution of individual ESMO risk factors [Citation8] was investigated using Cox’s proportional hazards regression with censoring for cases lost to follow-up or death.

Statistics were calculated with R version 3.6.1 (Vienna, Austria). Differences were considered statistically significant if p≤.05. The study was approved by the regional ethics committee (2013/093) and the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (2019/06156).

Results

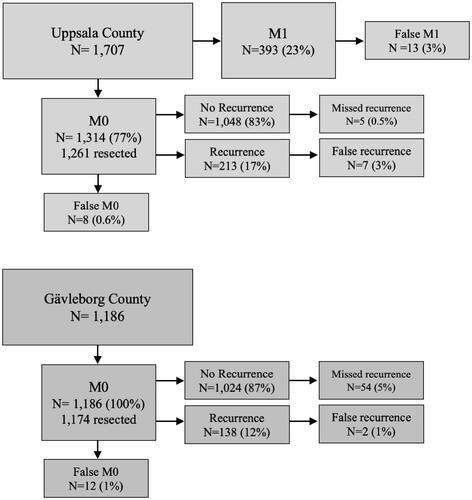

Between January 2010 and December 2018, 1707 patients living in the Uppsala region at the time of diagnosis were identified in the registry with 1736 cancers. Of these, 1314 (77%) did not have any metastases (M0) and 1261 were resected (including polypectomies, 809 colon, 452 rectum). In Gävleborg, 1186 patients, with 1233 cancers, had surgery for stage I–III disease; 1174 were resected (800 colon, 374 rectum).

Confirmation of registered metastases (Uppsala region) or recurrences (both regions)

Uppsala

All patients diagnosed with CRC were investigated. The number of CRC patients, whether diagnosed with synchronous metastases or not and if recurrence-free or not is shown in . Evidence of metastatic disease in patients registered as M1 at diagnosis was seen in all but eight (3%) colon cancer patients and in all but five (4%) rectal cancer patients. Reasons were misclassified liver or lung lesions, either confirmed by histology after removal, spontaneous disappearance of the lesion or at least 2 years without progression in the absence of tumor-specific treatment. The opposite, namely that patients had synchronous disease, meaning metastases diagnosed at the latest at surgery or initial work-up, but not registered, was uncommon; seven (0.8%) colon cancers and one (1%) rectal cancer. In total, 388 (23%) patients had M1 disease at diagnosis. Of the 213 recurrences registered, six (5%) colon cancers and one (0.7%) rectal cancer were wrongly registered. Reasons were in all probability in four patients a new colon cancer, in two another malignancy (lung cancer, malignant lymphoma), and in one a hemangioma.

Figure 1. Validation cohort flowchart. Patients from Uppsala region (all stages) and Gävleborg region (stage I–III) were included for chart review and validation. Percentages calculated from previous block. Resected patients (Uppsala cohort) and the stage I–III cohort from Gävleborg included also non-radically operated patients but at risk for having a non-registered recurrence.

Gävleborg

Patients with stage I–III CRC were investigated. The number of patients and if recurrence-free or not is shown in . Patients with synchronous disease, but registered as M0, were uncommon: eight (1%) colon cancers and four (1%) rectal cancers; of these, eight were registered as recurrent. In the other 138 registered recurrences, one (1%) colon cancer and one (1%) rectal cancer were wrongly registered. Reasons were a benign liver lesion and another malignancy.

Non-registered recurrences

In order to understand mechanisms behind missed recurrences, we divided them according to follow-up routines (CT of the thorax and abdomen and CEA after 1 and 3 years) and the guidelines for reporting any recurrence (once diagnosed and after 3 and 5 years). For simplicity, we describe the results according to calendar year of primary tumor surgery in (2010–2014 with at least 5-year follow-up, 2015–2016 with between 3 and 5 years, 2017 with 2–3 years, and 2018 with at least 1 year of follow-up).

Table 1. Recurrences not registered in the registry from the two regions of non-metastatic colorectal cancer patients.

Uppsala

No patient with a follow-up exceeding 5 years had a missed recurrence and only one (0.4%) with a follow-up between 3 and 5 years. In patients diagnosed during 2017–2018, four recurrences diagnosed less than 6 months before the data file was created in January 2020 were not registered. Of the 809 recurrence-free colon cancer patients, 0.4% had a non-registered recurrence. In the 452 recurrence-free rectal cancer patients, the single non-registered recurrence (0.2%) was a local recurrence detected at the 1-year follow-up after an endoscopic resection.

Gävleborg

In patients operated between 2010 and 2014 (630 patients), 16 (3%) recurrences were not reported (of which seven occurred after 5 years). For the years 2015 to 2018, the proportion of unregistered recurrences was between 5 and 10% ( and Supplementary table 1). There were 389 (16%) recurrences in the entire material of 2363 radically operated CRC patients in stage I–III. A Kaplan–Meier plot highlighting the difference between registered recurrences and all recurrences after validation is available in Supplementary figure 1.

Stage-stratified colon cancer recurrence risks after validation of recurrence data in the two regions

In a new transcript performed after completion of the validation study, 1147 colon cancers were diagnosed in 1120 patients in Uppsala of which 844 had stage I–III. In Gävleborg, 836 stage I–III colon cancers in 802 patients were included. All errors possible to correct (chiefly lack of registration of a recurrence) had then been corrected, whereas errors not possible to correct (already registered metastases or recurrences, principle of ‘not to un-ring the bell’) were kept track of and corrected in the research file prior to analysis. In case of synchronous CRC, the least advanced and in case of metachronous CRC, the last diagnosed was removed prior to analysis.

To investigate the recurrence risk, patients where no resection was performed (n = 46), where resection was not radical (n = 87) or had neo-adjuvant chemotherapy (n = 45, mainly those with a locally advanced non- or difficult-to-resect tumor) were excluded. Patient characteristics of the included 1416 radically operated stage I–III patients with non-metastatic disease (M0) are described in . Median follow-up was 60 months (minimum 15 months, maximum 128 months) in alive and recurrence-free patients.

Table 2. Demographics of non-metastatic colon cancer patients in two population-based Swedish Colorectal Cancer cohorts diagnosed between 2010 and 2018.

Of the 1416 patients with a radically operated colon cancer diagnosed between 2010 and 2018, 217 (15%) patients have had a recurrence and 457 (32%) patients had died before April or June 2020. The 3- and 5-year recurrence risk in all stages together was 14% and 17%. These risks were 7% and 10% in stage II and 28% and 31% in stage III, respectively. The 3- and 5-year recurrence risk were calculated in stage II and III for low-, intermediate- (only stage II), and high-risk patients () in accordance with the latest ESMO guidelines [Citation8]. Eight recurrences occurred after five years, of which two occurred after seven years. The recurrence risk in patients being recurrence-free after five years was 2% in stage II and 1% in stage III. The five-year recurrence risk among the 132 resected but excluded patients was 32%.

Table 3. Recurrence rates at 3 and 5 years after radical surgery in a Swedish population-based colon cancer patient cohort diagnosed between 2010 and 2018 according to whether adjuvant therapy was initiated or not.

The five-year recurrence risk for stage II colon cancer patients was 6% in the low-risk and 9% in the intermediate-risk groups. Stage II high-risk patients and stage III low-risk patients had similar recurrence risks at three and five years (23% vs. 22% and 23% vs. 26%). The five-year recurrence risk was 43% for stage III high-risk patients. The recurrence risk among patients where adjuvant treatment was initiated was higher for apparent low- and intermediate-risk patients in stage II while it was lower for patients classified as stage II high-risk and stage III. The recurrence risk stratified by stage and risk group is illustrated in Supplementary figure 2.

The hazard ratios for ESMO risk factors (except CEA) were investigated in colon cancer stage II (n = 607) and III (n = 528) separately (). pT-stage, vascular, and perineural invasion were associated with worse prognosis in unadjusted regressions in stage II. Additionally, pN, obstruction, and malignancy grade were correlated with worse prognosis in stage III. In adjusted analyses, vascular invasion was the only factor significantly associated with worse prognosis in stage II. pN and obstruction were also significant in stage III. The recurrence risk increased with increasing number of risk factors, and patients with high-risk features (pT4 and/or <12 investigated nodes) had worse prognosis than patients without. Only 44 (4%) patients had fewer than 12 nodes investigated. When emergency presentation due to obstruction was considered in addition to the ESMO risk groups in stage III recurrence risks at 5 years were 17% in low-risk and 39% in high-risk elective patients. In patients presenting with obstruction, it was 42% in low-risk and 55% in high-risk stage III (presented by adjuvant treatment status in Supplementary table 2).

Table 4. Results from unadjusted and adjusted Cox regressions for ESMO risk factors in 607 stage II colon cancer patients and 528 stage III colon cancer patients.

Discussion

After complete validation against the clinical records, the registration of patients in two regions in Sweden diagnosed with CRC during a nine-year period was found to (1) have high validity and (2) substantiate that the recurrence risk after radical colon cancer surgery is less than previously reported. This finding is important since outdated recurrence risks are still the basis for current recommendations governing the use of adjuvant chemotherapy [Citation11]. Further, the registration of synchronous metastatic disease also carries high validity for studies of non-selected patient groups.

At the university hospital, with a special interest in the registry, CRC research, and a prospective biobank project [Citation30] reporting of recurrences to the SCRCR is done more rapidly following the recommendations than at the county hospital where reporting is frequently not done until a request is sent from the registry, there were no missing recurrences in the patients operated upon at least 5 years ago and only one missed recurrence after 3 years [Citation30]. Where no such extraordinary interest was present, the reporting was not as complete but recurrence rates in patients operated upon at least five years ago was only off by 2 percentage points. In patients with shorter follow-up than five years, where only one request from the SCRCR secretariat was present, the reporting was less accurate, and the recurrence risk underestimated. This is probably the situation in many regions where registration of recurrences is not done spontaneously, but on demand. A theory for why reporting got worse at the university hospital in 2017–2018 is that the registry introduced a tabbed interface. Similarly, in Gävleborg, the system for handling electronic patient records was changed in 2016, hiding all previous information in a separate database.

In order to overcome the obstacles of poor registration in population registers, a US study stated that ‘population-based registries given intense support and resources can capture recurrence and offer a generalizable picture of cancer outcomes’ [Citation31]. In Sweden, it is the duty of individual hospitals to feed the quality registries with proper and complete data, but the registries are voluntary and rely on the departments to provide enough resources to complete data. However, the motif for all departments to have their data as complete as possible is strong since anonymized key data per hospital is released yearly with rankings [Citation26]. Further, the quality registries are excellent resources for research [Citation32] and none wants to have incomplete or poor data.

Forty-five percent of CRC patients undergo surgery in regions with university clinics, and 55% of these are operated upon at the university hospitals. In addition, several non-university hospitals have a strong research presence suggesting that the Uppsala region data may be transferable to 50–60% of the total population, while the Gävleborg data may be representative for the rest. The five-year recurrence rate for patients operated upon at least five years ago should then be reliable to within 1–2%. Even if a reminder is sent to the operating department after 3 years, this appears to be insufficient to reach high coverage of recurrences in a region like Gävleborg. Recurrences after five years are not captured to the same extent, if at all, and should not be used as a measure without review of the patient records.

The recurrence risk after validation was low in the low and intermediate risk groups in stage II, lower than previously reported in the low-risk group (6% vs. 9%, 95% CI 7–11% in patients operated 2007–2012) [Citation3,Citation11,Citation25]. The high-risk group in stage II had a similar risk to what has been previously reported and is high enough to motivate adjuvant chemotherapy. Stage II low and intermediate risk patients who received chemotherapy probably did so due to risk factors not accounted for by the established risk factors as recorded in the SCRCR.

The risk factors of recurrence recommended by ESMO in stage II colon cancer were investigated in both unadjusted and adjusted analyses with no effect from the number of nodes or malignancy grade, the latter being similar to a recent Finish study in colon cancer stage II [Citation33]. The lack of effect from inadequate node investigation might be due to the low number of patients with fewer than 12 investigated nodes (n = 44). We have previously shown that emergency presentation had a major effect on recurrence risks [Citation3] and we believe it is inappropriate not to include obstruction/emergency presentation as a risk factor in stage III.

Strengths and weaknesses

The major strength is that all individuals with a diagnosed CRC in a defined population could be identified and complete follow-up information obtained from all of them. Thus, all clinically detected recurrences were identified. Having an ambition to create a large patient population with accurate information about whether they were disease-free after surgery and if recurrence diagnosis was complete and accurate, and not only estimate how valid the registration is, we chose to scrutinize all records and not strictly follow recommendations [Citation27–29]. In a previous evaluation of the SCRCR using the reabstraction method of a random national sample, the exact agreement in non-missing records of metastatic disease pre- and postoperatively was 96% [Citation18], slightly less than reported here. The evaluation of whether the diagnosis and registration of metastatic or recurrent disease may be open to criticism but we adopted a rigorous approach in order not to introduce bias.

The distinction between a new primary and a recurrence can be problematic, but in the 10 cases identified, although initially registered as a recurrence, the clinical records told that it was a metachronous cancer (new site, morphological appearance, histological differences and in a few cases, another RAS/BRAF/PIK3CA mutation).

Since follow-up routines in Sweden are not intensive, it is possible that patients dying from other reasons may have recurred, if death had not come in between. Autopsy rates are low in Sweden, why an undiagnosed recurrence cannot be excluded, but a clear death reason was noted in most cases. Although persons living in Sweden may move from one place to another, this is uncommon among the age groups that have had colon cancer [Citation34]. Further, patients who have been treated for cancer practically always go to or are referred to the nearest hospital or, if operated, to the operating hospital. The number of patients in certain subgroups was not extensive why the relative importance of clinico-pathological variables is open for uncertainties. There is always a possibility that the number of patients with subclinical disease, needing adjuvant therapy, is larger than the number with detected recurrence, but the extent of this is probably small and not questioning our general conclusion that the recurrence risks are less than in the past.

Conclusion

The validity of recurrences registered in the registry differed between the two regions, presumably due to different practices for when recurrences are reported and who does the reporting. Time seems to be the most important factor for valid data. We estimate that the five-year recurrence rate reported to the registry only differs by 1–2% from the true recurrence rate in patients operated upon at least five years ago, while the recurrence rate in patients operated more recently cannot be taken at face value.

In this material, where no recurrences were unreported, the recurrence rate in low and intermediate (introduced by ESMO in their latest recommendation) risk, stage II colon cancer is lower than what has previously been reported (6 vs. 9%) [Citation3]. The risk factors currently recommended by ESMO in colon cancer stage II clearly identify a large group of patients where adjuvant treatment is highly questionable, while for patients in the intermediate group, better tools for risk stratification are needed. Better stratification in stage III colon cancer is possible by incorporating emergency presentation/obstruction as a risk factor.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (6.9 MB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, et al. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6):394–424.

- Kodeda K, Nathanaelsson L, Jung B, et al. Population-based data from the Swedish Colon Cancer Registry. Br J Surg. 2013;100(8):1100–1107.

- Osterman E, Glimelius B. Recurrence risk after up-to-date colon cancer staging, surgery, and pathology: analysis of the entire Swedish population. Dis Colon Rectum. 2018;61(9):1016–1025.

- Benitez Majano S, Di Girolamo C, Rachet B, et al. Surgical treatment and survival from colorectal cancer in Denmark, England, Norway, and Sweden. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20(1):74–87.

- Shah MA, Renfro LA, Allegra CJ, et al. Impact of patient factors on recurrence risk and time dependency of oxaliplatin benefit in patients with colon cancer: analysis from modern-era adjuvant studies in the Adjuvant Colon Cancer End Points (ACCENT) Database. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(8):843–853.

- Schmoll HJ, Van Cutsem E, Stein A, et al. ESMO Consensus Guidelines for management of patients with colon and rectal cancer. A personalized approach to clinical decision making. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(10):2479–2516.

- NCCN. Guidelines rectal cancer, version 6.2020. NCCNorg; 2020; [cited 2020 Sep 10].

- Argiles G, Tabernero J, Labianca R, et al. Localised colon cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2020;31(10):1291–1305.

- Pahlman LA, Hohenberger WM, Matzel K, et al. Should the benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy in colon cancer be re-evaluated? J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(12):1297–1299.

- Bockelman C, Engelmann BE, Kaprio T, et al. Risk of recurrence in patients with colon cancer stage II and III: a systematic review and meta-analysis of recent literature. Acta Oncol. 2015;54(1):5–16.

- Osterman E, Hammarstrom K, Imam I, et al. Recurrence risk after radical colorectal cancer surgery – less than before, but how high is it? Cancers. 2020;12(11):3308.

- Heald RJ, Ryall RDH. Recurrence and survival after total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer. Lancet. 1986;28:1479–1482.

- Bokey L, Chapuis PH, Chan C, et al. Long-term results following an anatomically based surgical technique for resection of colon cancer: a comparison with results from complete mesocolic excision. Colorectal Dis. 2016;18(7):676–683.

- Iversen LH, Green A, Ingeholm P, et al. Improved survival of colorectal cancer in Denmark during 2001–2012 – the efforts of several national initiatives. Acta Oncol. 2016;55(Suppl. 2):10–23.

- Feinstein AR, Sosin DM, Wells CK. The Will Rogers phenomenon. Stage migration and new diagnostic techniques as a source of misleading statistics for survival in cancer. N Engl J Med. 1985;312(25):1604–1608.

- Glimelius B, Myklebust TÅ, Lundqvist K, et al. Two countries – two treatment strategies for rectal cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2016;121(3):357–363.

- Påhlman L, Bohe M, Cedermark B, et al. The Swedish rectal cancer registry. Br J Surg. 2007;94(10):1285–1292.

- Moberger P, Skoldberg F, Birgisson H. Evaluation of the Swedish Colorectal Cancer Registry: an overview of completeness, timeliness, comparability and validity. Acta Oncol. 2018;57(12):1611–1621.

- Matsuda C, Ishiguro M, Teramukai S, et al. A randomised-controlled trial of 1-year adjuvant chemotherapy with oral tegafur–uracil versus surgery alone in stage II colon cancer: SACURA trial. Eur J Cancer. 2018;96:54–63.

- Sorbye H, Pfeiffer P, Cavalli-Bjorkman N, et al. Clinical trial enrollment, patient characteristics, and survival differences in prospectively registered metastatic colorectal cancer patients. Cancer. 2009;115(20):4679–4687.

- Ludmir EB, Mainwaring W, Lin TA, et al. Factors associated with age disparities among cancer clinical trial participants. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5(12):1769.

- Hovdenak Jakobsen I, Juul T, Thaysen HV, et al. Differences in baseline characteristics and 1-year psychological factors between participants and non-participants in the randomized, controlled trial regarding patient-led follow-up after rectal cancer (FURCA). Acta Oncol. 2019;58(5):627–633.

- In H, Bilimoria KY, Stewart AK, et al. Cancer recurrence: an important but missing variable in national cancer registries. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21(5):1520–1529.

- In H, Simon CA, Phillips JL, et al. The quest for population-level cancer recurrence data; current deficiencies and targets for improvement. J Surg Oncol. 2015;111(6):657–662.

- Osterman E, Mezheyeuski A, Sjoblom T, et al. Beyond the NCCN risk factors in colon cancer: an evaluation in a Swedish Population-Based Cohort. Ann Surg Oncol. 2020;27(4):1036–1945.

- RCC. Regionala rapporter; [cited 2020 Dec 8]. Available from: https://wwwcancercentrumse/norr/cancerdiagnoser/tjocktarm-andtarm-och-anal/tjock–och-andtarm/kvalitetsregister/. 2020

- Bray F, Parkin DM. Evaluation of data quality in the cancer registry: principles and methods. Part I: comparability, validity and timeliness. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(5):747–755.

- Parkin DM, Bray F. Evaluation of data quality in the cancer registry: principles and methods. Part II. Completeness. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(5):756–764.

- Lambe M, Rejmyr-Davis M. Validering av kvalitetsregister på INCA. Version 2; 2014; [cited 2020 Dec 8]. Available from: https://wwwcancercentrumse/globalassets/vara-uppdrag/kunskapsstyrning/kvalitetsregister/validering/manual-for-validering-av-kvalitetsregister-inom-cancerpdf?support

- Glimelius B, Melin B, Enblad G, et al. U-CAN: a prospective longitudinal collection of biomaterials and clinical information from adult cancer patients in Sweden. Acta Oncol. 2018;57(2):187–194.

- Thompson TD, Pollack LA, Johnson CJ, et al. Breast and colorectal cancer recurrence and progression captured by five U.S. population-based registries: findings from National Program of Cancer Registries patient-centered outcome research. Cancer Epidemiol. 2020;64:101653.

- Lysholm J, Lindahl B. Strong development of research based on national quality registries in Sweden. Ups J Med Sci. 2019;124(1):9–11.

- Heerva E, Valiaho V, Salminen T, et al. An easily adaptable validated risk score predicts cancer-specific survival in stage II colon cancer. Acta Oncol. 2020;59(12):1503–1507.

- SCB Official Statistics of Sweden; 2020; [cited 2020 Dec 8]. Available from: https://www.scb.se/hitta-statistik/sverige-i-siffror/manniskorna-i-sverige/flyttar-inom-sverige/