Abstract

Background

Treatment with rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP) is standard of care first line treatment for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), though outcomes remain suboptimal.

Methods

We performed a systemic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials comparing the efficacy and safety of R-CHOP vs. R-CHOP + X (addition of another drug to R-CHOP) as first line treatment for DLBCL. We searched Cochrane Library, PubMed and conference proceedings up to September 2020.

Results

Our search yielded ten trials including 4206 patients. The added drug was bortezomib or lenalidomide in three trials each, and gemcitabine, bevacizumab and ibrutinib, each drug in one trial. R-CHOP + X was associated with statistically significant improved disease control (HR 0.88, 95% CI 0.78–0.99). The point estimate was in favor of improved overall survival with R-CHOP + X (hazard ratio (HR) 0.87, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.75–1.00), although this was not statistically significant. Subgroup analysis revealed improved disease control with the addition of lenalidomide and in patients younger than 60 years. R-CHOP + X was associated with an increase in serious adverse events and grade III/IV hematologic toxicity.

Conclusion

The addition of another drug to frontline R-CHOP treatment for DLBCL did not result in a significant improvement in OS, although we did observe improved disease control compared to R-CHOP, perhaps most evident with the addition of lenalidomide. Yet, RCHOP + X was associated with an increased risk for serious and hematological adverse events. Further studies could reveal subgroups that would benefit most from augmentation of standard R-CHOP.

Background

During the last two decades, the research in diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL) has enabled improved biological molecular and cytogenetic understanding of the disease. The distinction of germinal center B-cell (GCB) and activated B-cell (ABC) DLBCL molecular subtypes has provided prognostic stratification [Citation1,Citation2]. Nevertheless, standard of care first line treatment has remained rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (RCHOP) for almost two decades [Citation3]. Approximately 40% of patients will have refractory DLBCL or early relapse when treated with RCHOP frontline therapy [Citation4]. Different protocols, such as dose-adjusted etoposide, prednisone, vincristine, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin and rituximab (DA-EPOCH-R) and obinutuzumab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (GCHOP) have failed to demonstrate improved efficacy in frontline DLBCL therapy compared to RCHOP [Citation5,Citation6]. Whether there is room for improvement is unclear, and prospective studies have recently examined whether the addition of various drugs to RCHOP (termed R-CHOP + X) could improve outcomes. The aim of this study was to compare the efficacy and safety of R-CHOP vs. R-CHOP + X as first line treatment for DLBCL.

Material and methods

We searched PubMed until September 2020, The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), published in The Cochrane Library, until September 2020, and the following conference proceedings: Annual Meeting of the American Society of Hematology (till December 2019), Annual Meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting (till May 2020), Annual Meeting of the European Hematology Association (till June 2020), and International Conference of Malignant Lymphoma (till June 2019). We cross‐searched the terms ‘diffuse large cell lymphoma’ or ‘aggressive lymphoma’ and similar terms, ‘RCHOP’ and ‘first line’ and similar terms. For PubMed, we added the Cochrane highly sensitive search term for identification of clinical trials. In addition, we scanned references of all included trials and reviews identified for additional studies.

Study selection

We included all randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing first line treatment with R-CHOP vs. R-CHOP + X (i.e. R-CHOP with the addition of another single drug) in patients with newly diagnosed DLBCL.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Two reviewers (O.P., R.G.) independently extracted data regarding case definitions, characteristics of patients, and outcomes from included trials. In the event of disagreement between the two reviewers regarding any of the above, a third reviewer (A.G.) extracted the data. Data extraction was discussed, and decisions were documented.

Two reviewers independently assessed the trials for the following domains: allocation concealment, generation of the allocation sequence, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data reporting, and selective outcome reporting. We made critical assessment separately for each domain and graded it as low, unclear, or high risk for bias according to the criteria specified in the Cochrane Handbook version 5.1.0.7 [Citation7].

Outcome measures

Primary outcome was overall survival (OS). Secondary outcomes included disease control, response rate (ORR), complete response (CR) rate and safety.

We defined disease control as any of the following outcomes: progression‐free survival (PFS), event‐free survival (EFS), or disease‐free survival (DFS) as reported in the original trials. The preferred outcome extracted for disease control was PFS, defined as time from randomization to progression or death from any cause. If data for PFS were not available, then we used DFS, defined as time from CR to relapse or death from any cause. If data for PFS and DFS were not available, we used EFS, as defined as time from randomization to failure of treatment including relapse, death, or toxicity due to treatment [Citation8].

Data synthesis and statistical analysis

We obtained data from aggregate statistics presented in the studies’ reports and used Peto’s method for time to event analysis. To obtain parameters for calculation of Peto’s method in the Review Manager software, we based our method on the article by Parmar et al. [Citation9] Odd ratios (ORs) and variances for time‐to‐event outcomes were estimated and pooled in Review Manager (version 5.3 for Windows; The Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, UK). An OR less than 1.0 was in favor of RCHOP + X therapy.

Relative risks (RRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for dichotomous data were estimated using the Mantel‐Haenszel method.

We assessed heterogeneity of trial results by the chi test of heterogeneity, and the I2 statistic of inconsistency [Citation10]. Statistically significant heterogeneity was defined as p less than 0.1 or an I2 statistic greater than 50%. We conducted the meta‐analysis using a fixed‐effect model (FEM), and in case of high heterogeneity, we used random‐effects model (REM).

We planned to perform subgroup analyses for OS and disease control by the type of additional drug added to RCHOP, by cell of origin (COO) and by age under 60 years.

Results

Description of trials

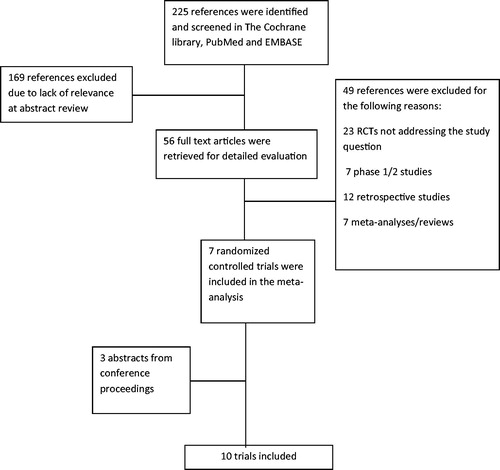

The literature search yielded 225 trials, of which 56 were considered as potentially relevant. Forty nine were excluded for various reasons (). Ten trials fulfilled the inclusion criteria, three of which were abstracts [Citation11–13], and seven published in peer review journals [Citation14–20]. The trials were published between the years 2010 and 2019. The added drug was bortezomib or lenalidomide in three trials each, and gemcitabine, bevacizumab, enzastaurin and ibrutinib - each drug in one trial. The characteristics of included trials are shown in .

Figure 1. Flow diagram of publications identified for study and exclusions. RCT randomized control trial.

Table 1. Characteristics of included trials.

Our analysis included 4206 patients. Median age of patients ranged between 50 and 83 years. Six trials included all DLBCL patients regardless of cell of origin [Citation11,Citation12,Citation14–16,Citation19], whereas four trials included only patients with non-GCB/ABC DLBCL [Citation13,Citation17,Citation18,Citation20].

Risk of bias of included trials

Five trials were judged at low risk of selection bias [Citation13–15,Citation17,Citation20]. In the other five trials, methods of allocation concealment and generation were not reported (two abstracts [Citation11,Citation12], three articles [Citation16,Citation18,Citation19]). Blinding of patients and personnel was done in two trials ([Citation13,Citation20], double blinding). All trials were judged at low risk of attrition bias, and all trials except one [Citation15] were judged at low risk of reporting bias, since clinically important outcomes including overall survival were well addressed. Further details can be found in supplementary Table S1.

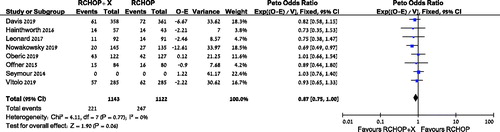

Primary outcome

Data from eight trials were available for analysis of OS [Citation11–13,Citation15–19]. The point estimate add in favor of improved overall survival with the addition of another drug to RCHOP, albeit without statistical significance, with HR 0.87, [95% CI 0.75–1.00, I2 = 0%, 3343 patients, 8 trials], (). A subgroup analysis of OS for both bortezomib and lenalidomide showed similar point estimates, without a statistically significant effect on OS with the addition of either drug: HR 0.82 [95% CI 0.62–1.08, I2 = 0%, 1288 patients, 3 trials] and HR 0.84 [95% CI 0.68–1.04, I2 = 0%, 1168 patients, 3 trials], respectively (supplementary Figures S1–S2). Subgroup analysis of patients with non-GCB DLBCL revealed no difference in OS, HR 0.89 [95% CI 0.67–1.18, I2 = 0%, 940 patients, 3 trials] (supplementary Figure S3).

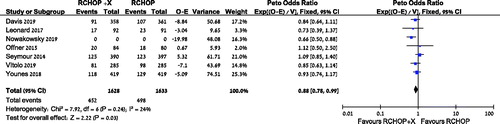

Secondary outcomes

There was a statistically significant improvement in disease control in the RCHOP + X arm vs. R-CHOP, HR 0.88 [95% CI 0.78–0.99, I2 = 24%, 3832 patients, 7 trials], (). A subgroup analysis also revealed improved disease control with the addition of lenalidomide to RCHOP, HR 0.74 [95% CI 0.61–0.91, I2 = 32%, 919 patients, 2 trials] (supplementary Figure S4). However, subgroup analysis of the addition of bortezomib revealed no difference in disease control, HR 0.84 [95% CI 0.66–1.07, I2 = 0%, 1288 patients, 3 trials] (supplementary Figure S5). Subgroup analysis of patients younger than 60 years revealed improved disease control, HR 0.52 [95% CI 0.36-0.74, I2 = 0%, 2 trials] (supplementary Figure S6). There was no statistical difference with the addition of another drug to RCHOP in the non-GCB DLBCL subgroup analysis, HR 0.88 [95% CI 0.75-1.04, I2 = 0%, 2022 patients, 5 trials] (supplementary Figure S7).

Figure 3. Disease control of patients treated with R‐CHOP + X compared with RCHOP. CI: confidence interval; O: observed; E: expected.

The ORR and CR rates were similar in the two arms (RR 0.98 [95% CI 0.95–1.02, I2 = 60%, 3173 patients, 9 trials], and RR 0.99 [95% CI 0.94–1.05, I2 = 35%, 2926 patients, 8 trials], respectively).

Safety

Five trials (N = 2340) reported serious adverse events. There was a significant increase in serious adverse events in the R-CHOP + X group vs. control, RR 1.35 [95% CI 1.23–1.47. I2 = 66%]. Eight trials (N = 2530) reported hematologic toxicity: Rates of grade III/IV anemia and thrombocytopenia were significantly higher in the RCHOP + X arm as compared to R-CHOP (RR 1.47 [95% CI 1.18–1.82, I2 = 37%, 2530 patients, 8 trials] and RR 2.54 [95% CI 1.60–4.04, I2 = 63%, 2281 patients, 7 trials], respectively). There was no difference in rates of grade III/IV neutropenia in both arms (RR 1.11 [95% CI 0.98–1.27, I2 = 71%, 2530 patients, 8 trials]).

Discussion

This systemic review and meta-analysis showed that the addition of an extra drug to the conventional first line R-CHOP regimen in patients with newly diagnosed DLBCL did not result in a statistically significant improvement in OS, though the point estimate was in favor of improved overall survival with R-CHOP + X. We did observe a small statistically significant improvement in disease control with R-CHOP + X compared to the standard R-CHOP, perhaps most evident with the addition of lenalidomide. We found no significant change in response rates. In addition, R-CHOP + X was associated with an increased risk for serious and grade III/IV hematological adverse events, especially anemia and thrombocytopenia. We found an improved disease control in the subgroups of lenalidomide and in patients younger than 60 years of age (26% and 48% improvement, respectively).

The pivotal trial by Coiffier et al. published in 2002, confirmed that adding rituximab to the CHOP backbone, yielded improved survival in frontline DLBCL, compared to CHOP alone [Citation21]. Ever since, attempts have been made to improve upon this regimen: Intensifying the chemotherapeutic regimen usually resulted in increased toxicity and/or insufficient improvement in efficacy [Citation5,Citation22]. Nonetheless, several trials showed improved outcomes in subgroups receiving intensified treatment. For example, rituximab, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vindesine, bleomycin, and prednisone (R-ACVBP) has been associated improved PFS and OS compared to RCHOP in younger patients with non-GCB DLBCL [Citation23]. Our findings also suggest that a younger age group might benefit from an intensified treatment regimen. We found a 48% improvement in PFS with RCHOP + X compared to RCHOP in patients younger than 60 years of age. We were able to include only two studies into our subgroup analysis of younger patients, one added ibrutinib to RCHOP [Citation20] and the second study added lenalidomide [Citation12]. The study by Younes et al. with ibrutinib demonstrated significant improvement not only in PFS, but also in OS [Citation20], however there was insufficient data from other studies to conduct a pooled survival analysis. Younger patients could potentially benefit more from regimen intensification due to better tolerance of treatment toxicity, enabling preserved dose intensity as well as reduced treatment related morbidity and mortality compared to elderly patients [Citation24]. This is exemplified by the higher rates of adverse events in patients above 60 years of age when ibrutinib was added to RCHOP in the study by Younes et al., leading to more cases of treatment discontinuation [Citation20].

Consolidation with frontline autologous HSCT for DLBCL was examined in several RCTs prior to and after the rituximab era with conflicting results, and a recent meta-analysis of RCTs conducted with rituximab-containing regimens showed no benefit for upfront transplant, even in high-risk populations. [Citation25] Trials with maintenance therapy for patients with DLBCL achieving CR/PR after frontline therapy have generally failed to show significant benefit, however a meta-analysis conducted by our group did reveal a reduced relapse rate and improved disease control with maintenance therapy, albeit with increased infection rate and no survival benefit [Citation26].

Changing certain aspects of the original RCHOP protocol has enabled some fine tuning. Recently, it has been observed that six cycles of RCHOP are non-inferior to eight cycles [Citation27].

Improved understanding of gene expression profiling in DLBCL has enabled the advent of novel therapeutics targeting crucial pathways believed to be drivers of the lymphoma pathogenesis, such as NFK-B in the ABC subtype of DLBCL [Citation3]. In an attempt to target patients with lymphoma harboring constitutive NFK-B activation, four trials included in this meta-analysis included only patients with specific COO categories. An additional trial conducted a preplanned analysis examining the effect of adding bortezomib to RCHOP in the GCB and ABC subtypes [Citation15]. Despite the potential mechanistic advantage for incorporating targeted drugs to RCHOP for patients with non-GCB DLBCL, we did not find a statistically significant advantage for RCHOP + X in this subgroup analysis. Study methodology and patient selection might partly explain the lack of efficacy. First, dosage of the added drug might be insufficient to provide clinical benefit, as proposed for instance by Leonard et al. regarding bortezomib [Citation17]. Furthermore, DLBCL subtype designation in three studies was obtained using immunohistochemistry (IHC) classification [Citation17,Citation18,Citation20], which is suboptimal compared to gene expression profiling (GEP), performed in one study [Citation12]. It is possible that studies which established COO prior to commencing therapy also had selection bias due to recruitment of relatively clinically stable patients, thus narrowing the possible advantage for treatment intensification. Study design allowing for rapid enrollment may enable better distinction between treatment arms, as suggested by the trend toward improved outcomes in the study by Nowakowski et al. [Citation12], which facilitated rapid time from diagnosis to treatment (median of 21 days).

To date no single study has shown positive results to improve on the standard RCHOP. Our analysis demonstrated a small (12%) yet statistically significant disease control advantage for patients treated with an addition of another drug to RCHOP. Variability in added drug efficacy might have decreased apparent superiority of some drugs. Most studies evaluated drugs that target different stages of the B-Cell receptor (BCR) pathway, which is constitutively activated in the ABC DLBCL subtype (lenlidomide, ibrutinib and bortezomib). It is possible that there may be an advantage for one drug over the other in this category. Lack of advantage in disease control in the bortezomib subgroup, compared to the 26% statistically significant improvement demonstrated in the lenalidomide subgroup may reflect suboptimal bortezomib dosing or insufficient blockade of the BCR pathway.

Our study has several limitations: There was variability in the studies, the most obvious one being the different type of drug used as an additive to RCHOP. Furthermore, also in trials examining the same added drug, there were some differences in dosing and scheduling. Additionally, as described in , the trials included varied in inclusion criteria, especially regarding COO, but also regarding other aspects of study design (primary endpoint, length of follow up) and disease characteristics (stage) and population (age) variables. This variability is manifested by mild heterogeneity in the analysis of disease control s (I2 = 24%). If this analysis was conducted with random effects model, rather than the fixed effect model, it could have resulted in a wider confidence interval and possibly a non-significant global effect for disease control. Therefore, the results should be addressed cautiously. Subgroup analyses were performed on a restricted number of trials, increasing potential bias and limiting study power.

R-CHOP still remains the ‘gold standard‘ of treatment for DLBCL. In this meta-analysis we did not observe a statistically significant improvement in OS with the addition of another drug to this regimen. In aggressive lymphoma, it is still not completely clear if a benefit in PFS can translate into an OS benefit. OS is still the gold standard primary efficacy endpoint for evaluating treatment strategies for DLBCL [Citation28]. A signal toward improved disease control with RCHOP + X in this meta-analysis suggests that perhaps certain subgroups could benefit from the addition of an additional drug to this regimen. This may be true for younger patients, who may be able to better tolerate more intensive treatment, although we found only two studies with adequate PFS data for patients under the age of 60 years. This may also be true for the addition of lenalidomide to RCHOP, which exhibited benefit in disease control. Future trials should assess the addition of new drugs to the RCHOP backbone in specific populations and settings.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (167.6 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Alizadeh AA, Eisen MB, Davis RE, et al. Distinct types of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma identified by gene expression profiling. Nature. 2000;403(6769):503–511.

- Rosenwald A, Wright G, Chan WC, et al. The use of molecular profiling to predict survival after chemotherapy for diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(25):1937–1947.

- Davies A. Tailoring front-line therapy in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: who should we treat differently? Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2017;2017(1):284–294.

- Mondello P, Mian M. Frontline treatment of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: beyond R-CHOP. Hematol Oncol. 2019;37(4):333–344.

- Bartlett NL, Wilson WH, Jung SH, et al. Dose-adjusted EPOCH-R compared with R-CHOP as frontline therapy for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: clinical outcomes of the phase III intergroup trial alliance/CALGB 50303. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(21):1790–1799.

- Vitolo U, Trněný M, Belada D, et al. Obinutuzumab or rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone in previously untreated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(31):3529–3537.

- Higgins JPT TJ, Chandler J, Cumpston M, et al., editors. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 6.0 (updated July 2019). Cochrane. 2019. http://www.training.cochrane.org/handbook

- Cheson BD, Pfistner B, Juweid ME, et al. Revised response criteria for malignant lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(5):579–586.

- Parmar MK, Torri V, Stewart L. Extracting summary statistics to perform meta-analyses of the published literature for survival endpoints. Statist Med. 1998;17(24):2815–2834.

- Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21(11):1539–1558.

- Lucie Oberic MP, Peyrade F, Maisonneuve H, et al. Sub-cutaneous rituximab-miniCHOP versus sub-cutaneous rituximab-miniCHOP + lenalidomide (R2-miniCHOP) in diffuse large B cell lymphoma for patients of 80 years old or more (SENIOR study). A multicentric randomized phase III study of the lysa. Blood. 2019;134(Supplement_1):352–352.

- Nowakowski G, Hong F, Scott D, et al. Addition of lenalidomide to R‐CHOP (R2CHOP) improves outcomes in newly diagnosed diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL): first report of ECOG‐ACRIN1412 a randomized phase 2 US intergroup study of R2CHOP vs R‐CHOP. Hematol Oncol. 2019;37(S2):37–38.

- Vitolo U, Witzig T, Gascoyne R, et al. ROBUST: First report of phase III randomized study of lenalidomide/R‐CHOP (R2‐CHOP) vs placebo/R‐CHOP in previously untreated ABC‐type diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma. Hematol Oncol. 2019;37(S2):36–37.

- Aurer I, Eghbali H, Raemaekers J, et al. Gem-(R)CHOP versus (R)CHOP: a randomized phase II study of gemcitabine combined with (R)CHOP in untreated aggressive non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma-EORTC lymphoma group protocol 20021 (EudraCT number 2004-004635-54). Eur J Haematol. 2011;86(2):111–116.

- Davies A, Cummin TE, Barrans S, et al. Gene-expression profiling of bortezomib added to standard chemoimmunotherapy for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (REMoDL-B): an open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20(5):649–662.

- Hainsworth JD, Arrowsmith ER, McCleod M, et al. A randomized, phase 2 study of R-CHOP plus enzastaurin vs R-CHOP in patients with intermediate- or high-risk diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2016;57(1):216–218.

- Leonard JP, Kolibaba KS, Reeves JA, et al. Randomized phase II study of R-CHOP with or without bortezomib in previously untreated patients with non-germinal center B-cell-like diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(31):3538–3546.

- Offner F, Samoilova O, Osmanov E, et al. Frontline rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and prednisone with bortezomib (VR-CAP) or vincristine (R-CHOP) for non-GCB DLBCL. Blood. 2015;126(16):1893–1901.

- Seymour JF, Pfreundschuh M, Trnĕný M, et al. R-CHOP with or without bevacizumab in patients with previously untreated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: final MAIN study outcomes. Haematologica. 2014;99(8):1343–1349.

- Younes A, Sehn LH, Johnson P, et al. Randomized phase III trial of ibrutinib and rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone in non-germinal center B-cell diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(15):1285–1295.

- Coiffier B, Lepage E, Briere J, et al. CHOP chemotherapy plus rituximab compared with CHOP alone in elderly patients with diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(4):235–242.

- Cunningham D, Hawkes EA, Jack A, et al. Rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisolone in patients with newly diagnosed diffuse large B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma: a phase 3 comparison of dose intensification with 14-day versus 21-day cycles. Lancet. 2013;381(9880):1817–1826.

- Recher C, Coiffier B, Haioun C, et al. Intensified chemotherapy with ACVBP plus rituximab versus standard CHOP plus rituximab for the treatment of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (LNH03-2B): an open-label randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2011;378(9806):1858–1867.

- Hamlin PA, Satram-Hoang S, Reyes C, et al. Treatment patterns and comparative effectiveness in elderly diffuse large B-cell lymphoma patients: a surveillance, epidemiology, and end results-medicare analysis. Oncologist. 2014;19(12):1249–1257.

- Epperla N, Hamadani M, Reljic T, et al. Upfront autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation consolidation for patients with aggressive B-cell lymphomas in first remission in the rituximab era: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer. 2019;125(24):4417–4425.

- Rozental A, Gafter-Gvili A, Vidal L, et al. The role of maintenance therapy in patients with diffuse large B cell lymphoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hematol Oncol. 2019;37(1):27–34.

- Laurie H Sehn AGC, Culligan DJ, Gironella M, et al. No added benefit of eight versus six cycles of CHOP when combined with rituximab in previously untreated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma patients: results from the international phase III GOYA study. Blood. 2018;132(Supplement 1):783–783.

- Qian Shi NS, Flowers C, Ou F-S, et al. Evaluation of Progression-Free Survival (PFS) as a surrogate endpoint for Overall Survival (OS) in first-line therapy for Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma (DLBCL): findings from the Surrogate Endpoint in Aggressive Lymphoma (SEAL) analysis of individual patient data from 7507 patients. Blood. 2016;128(22):4196–4196.